The Home Detoxification Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diazepam - Alcohol Withdrawal

Diazepam - alcohol withdrawal Why have I been prescribed diazepam? If a person stops drinking alcohol after a time of drinking too much they can experience withdrawal effects. These include “the shakes”, sweating, having fits, seeing things which are not there (hallucinations) and feeling anxious and low in mood. They can feel wound up and find it difficult to sleep. These withdrawal effects can be very uncomfortable and in extreme cases can be dangerous if they persist into “DTs” (delirium tremens). Diazepam is used to help reduce these withdrawal symptoms. It relieves anxiety and tension and aids sleep. Diazepam can also prevent fits. It controls the withdrawal symptoms until the body is free of alcohol and has settled down. This usually takes three to seven days from the time you stop drinking. What exactly is diazepam? Diazepam is a benzodiazepine. This group of medicines is also called anxiolytics or minor tranquillisers. Diazepam has many uses. It can be used to reduce symptoms of anxiety and insomnia, as well as to help people come off alcohol. Diazepam should only be prescribed and taken as a short course. Is diazepam safe to take? Diazepam is safe to take for a short period of time, but it doesn’t suit everyone. Below are a few conditions where diazepam may be less suitable. If any of these apply to you please tell your doctor or key-worker. If you have depression or a mental illness If you have lung disease or breathing problems, or suffer from liver or kidney trouble If you take any other medicines or drugs, including those on prescription and bought from a chemist If you take illicit drugs bought “on the street” If you are pregnant or breast-feeding What is the usual dose of diazepam? The dose of diazepam will usually be started at 10-20mg four times a day. -

Nottinghamshire Primary Care Alcohol Misuse Guidelines

Nottinghamshire Primary Care Alcohol Dependence Guidelines V5.2 Last reviewed: April Review date: August 2021 2022 Title Nottinghamshire Primary Care Alcohol Dependence Guidelines Version 5.2 Lead - Dr Stephen Willott, GP Windmill Practice, Nottingham; Clinical Lead for alcohol misuse, Nottingham Recovery Network and Public Health Department, Nottingham City Council Author / Tanya Behrendt, Senior Pharmacist (Nottingham City Locality), NHS Nottingham and Nottinghamshire CCG Nominated Apollos Clifton-Brown, Operational Manager, Nottingham Recovery Network Dr David Rhinds, Consultant Addictions Psychiatrist, Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust Lead Dr Kaanthan Jawahar, ST6 Old Age Psychiatry, Derbyshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust Hannah Godden, Mental Health Interface and Efficiencies Pharmacist, Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust/ NHS Nottingham and Nottinghamshire CCG Jill Theobald, Interface Efficiencies Pharmacist, NHS Nottingham and Nottinghamshire CCG Approval Date August 2019 Review Date August 2022 Section Contents Page Number i. Summary 2 1. Introduction 4 2. Scope 5 3. Aims of Community Detoxification 5 4. Identifying suitable patients 5 5. Medical risks of community detoxification 6 6. Risk reduction 6 7. Record keeping 7 8. Equipment 7 9. Preparation for home detoxification 7 10. Medication 8 11. Relapse prevention/Follow up 8 12. Reducing alcohol consumption in people with alcohol dependence 9 13. Potentially difficult situations 10 14. References and version control 10 Appendix A Diagnostic Criteria -

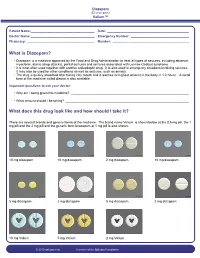

What Is Diazepam?

Diazepam (Di-a-ze-pam) Valium™ Patient Name: ___________________________________ Date: _____________________________________________ Doctor Name: ___________________________________ Emergency Number: ________________________________ Pharmacy: _____________________________________ Number: __________________________________________ What is Diazepam? • Diazepam is a medicine approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat all types of seizures, including absence, myoclonic, atonic (drop attacks), partial seizures and seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. • It is most often used together with another antiepileptic drug. It is also used in emergency situations involving seizures. It may also be used for other conditions as well as seizures, such as anxiety. • The drug is quickly absorbed after taking it by mouth and it reaches its highest amount in the body in 1-2 hours. A rectal form of the medicine called diastat is also available. Important questions to ask your doctor: • Why am I being given this medicine? _________________________________________________________________ • What amount should I be taking? ____________________________________________________________________ What does this drug look like and how should I take it? There are several brands and generic forms of the medicine. The brand name Valium is shown below at the 0.5 mg pill, the 1 mg pill and the 2 mg pill and the generic form lorazepam at 1 mg pill is also shown. 10 mg diazepam 10 mg diazepam 2 mg diazepam 10 mg diazepam 5 mg diazepam 2 mg diazepam 5 mg diazepam 2 mg diazepam 10 mg Valium 5 mg Valium 2 mg Valium © 2010 epilepsy.com A service of the Epilepsy Foundation Diazepam (Di-a-ze-pam) Valium™ Frequently Asked Questions: How do I take Diazepam? To use the tablet form: chew tablets and swallow or swallow the tablet whole. -

Drug and Alcohol Withdrawal Clinical Practice Guidelines - NSW

Guideline Drug and Alcohol Withdrawal Clinical Practice Guidelines - NSW Summary To provide the most up-to-date knowledge and current level of best practice for the treatment of withdrawal from alcohol and other drugs such as heroin, and other opioids, benzodiazepines, cannabis and psychostimulants. Document type Guideline Document number GL2008_011 Publication date 04 July 2008 Author branch Centre for Alcohol and Other Drugs Branch contact (02) 9424 5938 Review date 18 April 2018 Policy manual Not applicable File number 04/2766 Previous reference N/A Status Active Functional group Clinical/Patient Services - Pharmaceutical, Medical Treatment Population Health - Pharmaceutical Applies to Area Health Services/Chief Executive Governed Statutory Health Corporation, Board Governed Statutory Health Corporations, Affiliated Health Organisations, Affiliated Health Organisations - Declared Distributed to Public Health System, Ministry of Health, Public Hospitals Audience All groups of health care workers;particularly prescribers of opioid treatments Secretary, NSW Health Guideline Ministry of Health, NSW 73 Miller Street North Sydney NSW 2060 Locked Mail Bag 961 North Sydney NSW 2059 Telephone (02) 9391 9000 Fax (02) 9391 9101 http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/policies/ space space Drug and Alcohol Withdrawal Clinical Practice Guidelines - NSW space Document Number GL2008_011 Publication date 04-Jul-2008 Functional Sub group Clinical/ Patient Services - Pharmaceutical Clinical/ Patient Services - Medical Treatment Population Health - Pharmaceutical -

Risk Based Requirements for Medicines Handling

Risk based requirements for medicines handling Including requirements for Schedule 4 Restricted medicines Contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Summary of roles and responsibilities 3 3. Schedule 4 Restricted medicines 4 4. Medicines acquisition 4 5. Storage of medicines, including control of access to storage 4 5.1. Staff access to medicines storage areas 5 5.2. Storage of S4R medicines 5 5.3. Storage of S4R medicines for medical emergencies 6 5.4. Access to storage for S4R and S8 medicines 6 5.5. Pharmacy Department access, including after hours 7 5.6. After-hours access to S8 medicines in the Pharmacy Department 7 5.7. Storage of nitrous oxide 8 5.8. Management of patients’ own medicines 8 6. Distribution of medicines 9 6.1. Distribution outside Pharmacy Department operating hours 10 6.2. Distribution of S4R and S8 medicines 10 7. Administration of medicines to patients 11 7.1. Self-administration of scheduled medicines by patients 11 7.2. Administration of S8 medicines 11 8. Supply of medicines to patients 12 8.1. Supply of scheduled medicines to patients by health professionals other than pharmacists 12 9. Record keeping 13 9.1. General record keeping requirements for S4R medicines 13 9.2. Management of the distribution and archiving of S8 registers 14 9.3. Inventories of S4R medicines 14 9.4. Inventories of S8 medicines 15 10. Destruction and discards of S4R and S8 medicines 15 11. Management of oral liquid S4R and S8 medicines 16 12. Cannabis based products 17 13. Management of opioid pharmacotherapy 18 14. -

Retention Behaviour of Some Benzodiazepines in Solid-Phase Extraction Using Modified Silica Adsorbents Having Various Hydrophobicities

ACADEMIA ROMÂNĂ Rev. Roum. Chim., Revue Roumaine de Chimie 2015, 60(9), 891-898 http://web.icf.ro/rrch/ RETENTION BEHAVIOUR OF SOME BENZODIAZEPINES IN SOLID-PHASE EXTRACTION USING MODIFIED SILICA ADSORBENTS HAVING VARIOUS HYDROPHOBICITIES Elena BACALUM,a Mihaela CHEREGIb,* and Victor DAVIDb,* a Research Institute from University of Bucharest – ICUB, 36-46 M. Kogalniceanu Blvd., Bucharest, 050107, Roumania b University of Bucharest, Faculty of Chemistry, Department of Analytical Chemistry, 90 Panduri Ave, Bucharest – 050663, Roumania Received April 6, 2015 The retention properties of six benzodiazepines (alprazolam, bromazepam, diazepam, flunitrazepam, medazepam, and nitrazepam) on four different solid phase extraction silica 1.0 adsorbents with various hydrophobicities (octadecylsilica, octylsilica, phenylsilica, and cyanopropylsilica) were 0.8 H O investigated. The breakthrough curves showed a significant N retention of these compounds on octadecylsilica, octylsilica, 0.6 Br N phenylsilica, excepting alprazolam that has a poor retention on 0 C/C N octadecylsilica. These results can be explained by the 0.4 PHENYL CN hydrophobic character of studied benzodiazepines (octanol- C18 0.2 C8 Bromazepam water partition constant, log Kow, being situated within the interval 1.90-4.45). A poor retention on cyanopropylsilica was 0.0 observed for all studied compounds indicating that π-π and 0 102030405060708090100 Volume (mL) polar intermolecular interactions have a less significant role in their retention on this adsorbent. Generally, the breakthrough -

The In¯Uence of Medication on Erectile Function

International Journal of Impotence Research (1997) 9, 17±26 ß 1997 Stockton Press All rights reserved 0955-9930/97 $12.00 The in¯uence of medication on erectile function W Meinhardt1, RF Kropman2, P Vermeij3, AAB Lycklama aÁ Nijeholt4 and J Zwartendijk4 1Department of Urology, Netherlands Cancer Institute/Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Hospital, Plesmanlaan 121, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; 2Department of Urology, Leyenburg Hospital, Leyweg 275, 2545 CH The Hague, The Netherlands; 3Pharmacy; and 4Department of Urology, Leiden University Hospital, P.O. Box 9600, 2300 RC Leiden, The Netherlands Keywords: impotence; side-effect; antipsychotic; antihypertensive; physiology; erectile function Introduction stopped their antihypertensive treatment over a ®ve year period, because of side-effects on sexual function.5 In the drug registration procedures sexual Several physiological mechanisms are involved in function is not a major issue. This means that erectile function. A negative in¯uence of prescrip- knowledge of the problem is mainly dependent on tion-drugs on these mechanisms will not always case reports and the lists from side effect registries.6±8 come to the attention of the clinician, whereas a Another way of looking at the problem is drug causing priapism will rarely escape the atten- combining available data on mechanisms of action tion. of drugs with the knowledge of the physiological When erectile function is in¯uenced in a negative mechanisms involved in erectile function. The way compensation may occur. For example, age- advantage of this approach is that remedies may related penile sensory disorders may be compen- evolve from it. sated for by extra stimulation.1 Diminished in¯ux of In this paper we will discuss the subject in the blood will lead to a slower onset of the erection, but following order: may be accepted. -

Comparison of Short-And Long-Acting Benzodiazepine-Receptor Agonists

J Pharmacol Sci 107, 277 – 284 (2008)3 Journal of Pharmacological Sciences ©2008 The Japanese Pharmacological Society Full Paper Comparison of Short- and Long-Acting Benzodiazepine-Receptor Agonists With Different Receptor Selectivity on Motor Coordination and Muscle Relaxation Following Thiopental-Induced Anesthesia in Mice Mamoru Tanaka1, Katsuya Suemaru1,2,*, Shinichi Watanabe1, Ranji Cui2, Bingjin Li2, and Hiroaki Araki1,2 1Division of Pharmacy, Ehime University Hospital, Shitsukawa, Toon, Ehime 791-0295, Japan 2Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Pharmacy, Neuroscience, Ehime University Graduate School of Medicine, Shitsukawa, Toon, Ehime 791-0295, Japan Received November 7, 2007; Accepted May 15, 2008 Abstract. In this study, we compared the effects of Type I benzodiazepine receptor–selective agonists (zolpidem, quazepam) and Type I/II non-selective agonists (zopiclone, triazolam, nitrazepam) with either an ultra-short action (zolpidem, zopiclone, triazolam) or long action (quazepam, nitrazepam) on motor coordination (rota-rod test) and muscle relaxation (traction test) following the recovery from thiopental-induced anesthesia (20 mg/kg) in ddY mice. Zolpidem (3 mg/kg), zopiclone (6 mg/kg), and triazolam (0.3 mg/kg) similarly caused an approximately 2-fold prolongation of the thiopental-induced anesthesia. Nitrazepam (1 mg/kg) and quazepam (3 mg/kg) showed a 6- or 10-fold prolongation of the anesthesia, respectively. Zolpidem and zopiclone had no effect on the rota-rod and traction test. Moreover, zolpidem did not affect motor coordination and caused no muscle relaxation following the recovery from the thiopental-induced anesthesia. However, zopiclone significantly impaired the motor coordination at the beginning of the recovery. Triazolam significantly impaired the motor coordination and muscle relaxant activity by itself, and these impairments were markedly exacerbated after the recovery from anesthesia. -

Red with Nitrazepam and Placebo in Acute Emergency Driving Situations and in Monotonous Simulated Driving

109 A 1986 The Carry-over Effects of Triazolam Compa- red with Nitrazepam and Placebo in Acute Emergency Driving Situations and in Mono- tonous Simulated Driving Hans Laurell and Jan Törnroos Reprint from Acta Pharmacologica et toxicologica 1986 v Väg06/7 Efi/( Statens väg- och trafikinstitut (VTI) * 581 01 Linköping [St]tlltet Swedish Road and Traffic Research Institute * S-581 01 Linköping Sweden Acta pharmacol. et toxicol. 1986, 58, 182186. From the National Swedish Road and Traffic Research Institute, (V.T.I.), S-58 101 Linköping, Sweden The Carry-over Effects of Triazolam Compared with Nitrazepam and Placebo in Acute Emergency Driving Situations and in Monotonous Simulated Driving Hans Laurell and Jan Törnros (Received October 9, 1985; Accepted January 9, 1986) Abstract: Eighteen healthy volunteers of both sexes, aged 2034, were tested in the morning while undertaking real car driving avoidance manoeuvres and during monotonous simulated driving after 1 and 3 nights of medication with triazolam 0.25 mg, nitrazepam 5 mg or placebo. The study was a double-blind, randomized, cross-over study, where a minimum of 7 days wash-out separated the 3 treatment periods. Nitrazepam was found to impair performance in the simulated task after 1 but not after 3 nights of medication. Performance in the triazolam condition was not signicantly different from the other conditions on this task on either day. However, after one night of medication triazolam tended to score worse than placebo but better than nitrazepam. In real car driving a tendency was noted for nitrazepam to score worst, whereas the difference between placebo and triazolam was hardly noticeable. -

Pentameric Ligand-Gated Ion Channel ELIC Is Activated by GABA And

Pentameric ligand-gated ion channel ELIC is activated PNAS PLUS by GABA and modulated by benzodiazepines Radovan Spurnya, Joachim Ramerstorferb, Kerry Pricec, Marijke Bramsa, Margot Ernstb, Hugues Nuryd, Mark Verheije, Pierre Legrandf, Daniel Bertrandg, Sonia Bertrandg, Dennis A. Doughertyh, Iwan J. P. de Esche, Pierre-Jean Corringerd, Werner Sieghartb, Sarah C. R. Lummisc, and Chris Ulensa,1 aDepartment of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Laboratory of Structural Neurobiology, Catholic University of Leuven, 3000 Leuven, Belgium; bDepartment of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of the Nervous System, Medical University of Vienna, A-1090 Vienna, Austria; cDepartment of Biochemistry, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 1QW, United Kingdom; dPasteur Institute, G5 Group of Channel-Receptor, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 75724 Paris, France; eDepartment of Medicinal Chemistry, VU University Amsterdam, 1081 HV, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; fSOLEIL Synchrotron, 91192 Gif sur Yvette, France; gHiQScreen, CH-1211 Geneva, Switzerland; and hCalifornia Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125 Edited* by Jean-Pierre Changeux, Institut Pasteur, Paris Cedex 15, France, and approved September 10, 2012 (received for review May 24, 2012) GABAA receptors are pentameric ligand-gated ion channels in- marized in SI Appendix, Table S1). In addition, it has been volved in fast inhibitory neurotransmission and are allosterically suggested that the GABA carboxylate group is stabilized through modulated by the anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, and sedative-hypnotic electrostatic interactions with Arg residues on the principal and benzodiazepines. Here we show that the prokaryotic homolog ELIC complementary faces of the binding site (4, 7–9). For benzo- also is activated by GABA and is modulated by benzodiazepines diazepines, the individual contributions of residues in loops A–F with effects comparable to those at GABAA receptors. -

Calculating Equivalent Doses of Oral Benzodiazepines

Calculating equivalent doses of oral benzodiazepines Background Benzodiazepines are the most commonly used anxiolytics and hypnotics (1). There are major differences in potency between different benzodiazepines and this difference in potency is important when switching from one benzodiazepine to another (2). Benzodiazepines also differ markedly in the speed in which they are metabolised and eliminated. With repeated daily dosing accumulation occurs and high concentrations can build up in the body (mainly in fatty tissues) (2). The degree of sedation that they induce also varies, making it difficult to determine exact equivalents (3). Answer Advice on benzodiazepine conversion NB: Before using Table 1, read the notes below and the Limitations statement at the end of this document. Switching benzodiazepines may be advantageous for a variety of reasons, e.g. to a drug with a different half-life pre-discontinuation (4) or in the event of non-availability of a specific benzodiazepine. With relatively short-acting benzodiazepines such as alprazolam and lorazepam, it is not possible to achieve a smooth decline in blood and tissue concentrations during benzodiazepine withdrawal. These drugs are eliminated fairly rapidly with the result that concentrations fluctuate with peaks and troughs between each dose. It is necessary to take the tablets several times a day and many people experience a "mini-withdrawal", sometimes a craving, between each dose. For people withdrawing from these potent, short-acting drugs it has been advised that they switch to an equivalent dose of a benzodiazepine with a long half life such as diazepam (5). Diazepam is available as 2mg tablets which can be halved to give 1mg doses. -

Drugs of Abuse: Benzodiazepines

Drugs of Abuse: Benzodiazepines What are Benzodiazepines? Benzodiazepines are central nervous system depressants that produce sedation, induce sleep, relieve anxiety and muscle spasms, and prevent seizures. What is their origin? Benzodiazepines are only legally available through prescription. Many abusers maintain their drug supply by getting prescriptions from several doctors, forging prescriptions, or buying them illicitly. Alprazolam and diazepam are the two most frequently encountered benzodiazepines on the illicit market. Benzodiazepines are What are common street names? depressants legally available Common street names include Benzos and Downers. through prescription. Abuse is associated with What do they look like? adolescents and young The most common benzodiazepines are the prescription drugs ® ® ® ® ® adults who take the drug Valium , Xanax , Halcion , Ativan , and Klonopin . Tolerance can orally or crush it up and develop, although at variable rates and to different degrees. short it to get high. Shorter-acting benzodiazepines used to manage insomnia include estazolam (ProSom®), flurazepam (Dalmane®), temazepam (Restoril®), Benzodiazepines slow down and triazolam (Halcion®). Midazolam (Versed®), a short-acting the central nervous system. benzodiazepine, is utilized for sedation, anxiety, and amnesia in critical Overdose effects include care settings and prior to anesthesia. It is available in the United States shallow respiration, clammy as an injectable preparation and as a syrup (primarily for pediatric skin, dilated pupils, weak patients). and rapid pulse, coma, and possible death. Benzodiazepines with a longer duration of action are utilized to treat insomnia in patients with daytime anxiety. These benzodiazepines include alprazolam (Xanax®), chlordiazepoxide (Librium®), clorazepate (Tranxene®), diazepam (Valium®), halazepam (Paxipam®), lorzepam (Ativan®), oxazepam (Serax®), prazepam (Centrax®), and quazepam (Doral®).