Romanization of Deiotarus 95

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RHETORIC in the RED OCTOBER CAMPAIGN: EXPLORING the WHITE VICTIM IDENTITY of POST-APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA by WILLEMIEN CALITZ

RHETORIC IN THE RED OCTOBER CAMPAIGN: EXPLORING THE WHITE VICTIM IDENTITY OF POST-APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA by WILLEMIEN CALITZ A THESIS Presented to the School of Journalism and Communication and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science June 2014 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Willemien Calitz Title: Rhetoric in the Red October Campaign: Exploring the White Victim Identity of Post-Apartheid South Africa This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science degree in the School of Journalism and Communication by: Christopher Chavez Chairperson Pat Curtin Member Yvonne Braun Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation; Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2014 ii © 2014 Willemien Calitz iii THESIS ABSTRACT Willemien Calitz Master of Science School of Journalism and Communication June 2014 Title: Rhetoric in the Red October Campaign: Exploring the White Victim Identity in Post-Apartheid South Africa This study explores whiteness through a rhetorical analysis of the language used in a speech made at a Red October campaign rally in South Africa in October, 2013. The Red October campaign positions white South Africans as an oppressed minority group in the country, and this study looks at linguistic choices and devices used to construct a white victim identity in post-apartheid South Africa. This thesis considers gender, religion, race, culture, class and ethnicity as intersections that contribute to the discursive construction of whiteness in the new South Africa. -

South Orlando Baptist Church LIBRARY RECORDS by SUBJECT

South Orlando Baptist Church LIBRARY RECORDS BY SUBJECT Page 1 Friday, November 15, 2013 Find all records where any portion of Basic Fields (Title, Author, Subjects, Summary, & Comments) like '' Subject Title Classification Author Accession # Abandoned children Fiction A cry in the dark (Summerhill Secrets #5) JF Lewis, Beverly 6543 Abandoned houses Fiction Julia's hope (The Wortham Family Series #1) F Kelly, Leisha 5343 Abolitionists Frederick Douglass (Black Americans of Achievement) JB Russell, Sharman Apt. 8173 Abortion Fiction Choice summer (Nikki Sheridan Series #1) YA F Brinkerhoff, Shirley 7970 Shades of blue F Kingsbury, Karen 8823 Tilly : the novel F Peretti, Frank E. 6204 Abortion Moral and ethical aspects Abortion : a rational look at an emotional issue 241 Sproul, R. C. (Robert Charles) 1296 Abraham (Biblical patriarch) Abraham and his big family [videorecording] VHS C220.95 Walton, John H. 5221 Abraham, man of faith J221.92 Rives, Elsie 1513 Created to be God's friend : how God shapes those He loves 248.4 Blackaby, Henry T. 4008 Dragons (Face to face) J398.24 Dixon, Dougal 8517 The story of Abraham (Great Bible Stories) C221.92 Nodel, Maxine 3724 Abused children Fiction Looking for Cassandra Jane F Carlson, Melody 6052 Abused wives Fiction A place called Wiregrass F Morris, Michael 7881 Wings of a dove F Bush, Beverly 2498 Abused women Fiction Sharon's hope F Coyle, Neva 3706 Acadians Fiction The beloved land (Song of Acadia #5) F Oke, Janette 3910 The distant beacon (Song of Acadia #4) F Oke, Janette 3690 The innocent libertine (Heirs of Acadia #2) F Bunn, T. -

The Rise of the South African Reich

The Rise of the South African Reich http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.crp3b10036 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org The Rise of the South African Reich Author/Creator Bunting, Brian; Segal, Ronald Publisher Penguin Books Date 1964 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa, Germany Source Northwestern University Libraries, Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies, 960.5P398v.12cop.2 Rights By kind permission of Brian P. Bunting. Description "This book is an analysis of the drift towards Fascism of the white government of the South African Republic. -

2019 National and Provincial Elections Report of South Africa's Electoral Commission

2019 NATIONAL AND PROVINCIAL ELECTIONS REPORT sê YOUR X IS YOUR SAY 2019 National and Provincial Elections Report a 2019 NATIONAL AND PROVINCIAL ELECTIONS REPORT ii 2019 National and Provincial Elections Report CONTENTS FOREWORD BY THE CHAIRPERSON 1 ABOUT THE COMMISSION 3 OVERVIEW BY THE CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER 5 1. PRE-ELECTION PHASE LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK 11 Legislative framework 11 Delimitation of voting district boundaries 12 Voter Participation Survey 15 Infrastructure: voting station planning 17 Civic and democracy education 20 Communication campaign: Xsê, your X is your say! 25 Digital disinformation initiative 35 Recruitment of electoral staff 36 Elections training 40 Information and communication technology 41 Voter registration and the voters’ roll 47 Registration of political parties 54 Political parties and candidates 56 Litigation 57 2. ELECTION PHASE 60 Ballot papers, ballot boxes and other election materials 60 Special voting 65 Election day 67 Turnout and participation 67 Counting and results 70 Election observation 71 Objections and final results 72 Electoral justice 85 Electoral Code of Conduct and the Directorate for Electoral Offences 86 Financing the 2019 NPE 86 3. POST-ELECTION PHASE 91 Research: Election Satisfaction Survey 2019 91 ANNEXURES List of abbreviations and acronyms 97 Sample ballot papers 98 Election timetable 101 Seat calculation 105 Provincial view 107 2019 National and Provincial Elections Report iii Foreword by the Chairperson The 2019 National and Provincial Elections (NPE) were yet another uncompromising test of the entire gambit of our electoral democracy: from the legislative and regulatory framework to the people who run and participate in elections; the processes and systems that facilitate them; and the logistics, planning and preparations that go into laying a foundation for free and fair elections. -

Elections Preview by the Centre for Risk Analysis

APRIL 2019 FAST FACTS Elections Preview Editor-in-Chief Frans Cronje Editor Thuthukani Ndebele Head of Research Thuthukani Ndebele Authors Gabriel Crouse Katherine Brown Head of Information Tamara Dimant April 2019 Published by the Centre For Risk Analysis 2 Clamart Road, Richmond Johannesburg, 2092 South Africa P O Box 291722, Melville, Johannesburg, 2109 South Africa Telephone: (011) 482–7221 E-mail: [email protected] www.cra-sa.com The CRA helps business and government leaders plan for a future South Africa and identify policies that will create a more prosperous society. It uses deep-dive data analysis and fi rst hand political and policy information to advise groups with interests in South Africa on the likely long term economic, social, and political evolution of the country. While the CRA makes all reasonable eff orts to publish accurate information and bona fi de expression of opinion, it does not give any warranties as to the accuracy and completeness of the information provided. The use of such information by any party shall be entirely at such party’s own risk and the CRA accepts no liability arising out of such use. Cover design by InkDesign Typesetting by Martin Matsokotere CONTENTS Leader ...........................................................................................................................................2 Tables and Charts Overview ...................................................................................................................................................3 Political representation -

Publication No. 201906 Notice No. 25 Part 2 (Non Profit Companies)

CIPC PUBLICATION 31 May 2019 Publication No. 201906 Notice No. 25 Part 2 (Non Profit Companies) (AR DEREGISTRATIONS) Page 1 of 148 NOTICE IN TERMS OF SECTION 82 OF THE COMPANIES ACT, 2008 RELATING TO ANNUAL RETURN DEREGISTRATIONS OF COMPANIES AND CLOSE CORPORATIONS NOTICE 06 OF 2019 COMPANIES AND CLOSE CORPORATIONS CIPC PUBLICATION NOTICE 06 OF 2019 COMPANIES AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY COMMISSION NOTICE IN TERMS OF THE COMPANIES ACT, 2008 (ACT 71 OF 2008) THE FOLLOWING NOTICE RELATING TO COMPANIES AND CLOSE CORPORATION THAT HAS BEEN REFERRED FOR DERGISTRATION IN TERMS OF SECTION 82 OF THE COMPANIES ACT, ARE PUBLISHED FOR GENERAL INFORMATION. NO GUARANTEE IS GIVEN IN RESPECT OF THE ACCURACY OF THE PARTICULARS FURNISHED AND NO RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR ERRORS AND OMISSIONS OR THE CONSEQUENCES THEREOF. Rory Voller COMMISSIONER: CIPC Page 2 of 148 NOTICE IN TERMS OF SECTION 82 OF THE COMPANIES ACT, 2008 RELATING TO ANNUAL RETURN DEREGISTRATIONS OF COMPANIES AND CLOSE CORPORATIONS NOTICE 06 OF 2019 K2011100719 SEFAKO MAPOGO MAKGATHO MEMORIAL FOUNDATION K2011100762 THE ROCK OF TABERNACLE MINISTRIES K2011101301 CAREERTUBE K2011101440 BOPHELOKE LEFA HEALTH PROJECT K2011102046 LAUDIUM CHESS AND CHECKERS CLUB K2011102234 MMSPI YOUTH INITIATIVE K2011103069 ALEXANDRA EAGLES FOOTBALL CLUB K2011103299 NXUBA COMMUNITY CENTRE K2011103863 MALUNGHELO WORKERS ASSOCIATION K2011104794 HAND TO HAND WELFARE INTERNATIONAL K2011106935 OSKRAAL PLOT OWNERS ASSOCIATION K2011107815 MOUNTAIN OF HEALING AND DELIVERANCE MINISTRIES K2011107900 I PETERSIDE MINISTRIES -

An Analysis of the Politics and Ideology of the White Rightwing in Historical Context

University of Cape Town THE RIGHT IN TRANSITION: An analysis of the politics and ideology of the white rightwing in historical context University of Cape Town Department of Sociology Presented in fulfilment of the degree Master ofArts Sharyn Spicer December 1993 Supervisor: Me!Yin Goldberg .~----------------·-=------, The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to extend my thanks to all who contributed to this dissertation. In particular, I would like to thank Melvin Goldgerg ~ithout whose supervision this would not have been possible. I would also like to thank Paul Vaughan of Penbroke Design Studio for the final layout. Furthermore, I thank my bursars from the Centre for Scientific Development (CSD), as well as the Centre for African Studies for the travel grant. Finally, I would like to thank my friend Erika Schutze for proofreading at short noti,ce. 11 , , TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ___________________ iv INTRODUCTION ______________________ x CHAPTER ONE---------------------- 1 1.1 WHAT IS THE "RIGHTWING"? 3 1.1.1. The nature offightwing organizations: 9 1.2 PERSPECTIVES IN LITERATURE: 23 CHAPTER TWO ______________________ 32 2.1 NEW TREJ'\TJ>S, TACTICS, STRATEGIES: 1988 to 1993 33 2.2 VIOLENCE AATJ> THE RIGHTWING: 37 2.2. -

Party Name List Type Order Number Idnumber Full

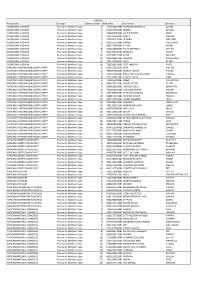

NPE2019 Party name List type Order number IDNumber Full names Surname ABORIGINAL KHOISAN Provincial: Northern Cape 1 7207215167085 FRANCOIS CORNELIUS CLARKE ABORIGINAL KHOISAN Provincial: Northern Cape 2 6002035043082 HENZEL APOLLIS ABORIGINAL KHOISAN Provincial: Northern Cape 3 7404200007083 JULEEN DENISE OWIES ABORIGINAL KHOISAN Provincial: Northern Cape 4 5402195014082 DANI°L MATJAN ABORIGINAL KHOISAN Provincial: Northern Cape 5 5609185170084 HENDRIK WILLEMSE ABORIGINAL KHOISAN Provincial: Northern Cape 6 6111055929086 SAMUEL STEENKAMP ABORIGINAL KHOISAN Provincial: Northern Cape 7 8606150092084 ELIZNA JACOBS ABORIGINAL KHOISAN Provincial: Northern Cape 8 9102045658080 RIAAN SEPTIMUS KLAASTE ABORIGINAL KHOISAN Provincial: Northern Cape 9 5902155020086 ABRAHAM OKKIES ABORIGINAL KHOISAN Provincial: Northern Cape 10 6611080135088 SONIA AMERIKA ABORIGINAL KHOISAN Provincial: Northern Cape 11 8309236667082 WILLIAM MONTSHIWA ABORIGINAL KHOISAN Provincial: Northern Cape 12 7001200059088 GAIRU BEUKES ABORIGINAL KHOISAN Provincial: Northern Cape 13 7308106178080 GERT WILLIAM RAATS AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Northern Cape 1 6601115225087 JAPIE VAN ZYL AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Northern Cape 2 7809275683081 KENNETH ELTON PHETOE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Northern Cape 3 7912015505083 ERICK KHOLISILE WIZEMAN STRAUSS AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Northern Cape 4 5511205831085 THAPELO JOHN THIPE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Northern Cape 5 7110255198087 -

Results Reports

Results Reports Detailed Results Results as at: 13/05/2019 04:22:28 PM Electoral Event: 2019 NATIONAL ELECTION Province: Western Cape Municipality: All Municipalities Registered Population: 3,128,567 Party Name Abbr. No. of Votes % Votes AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY ACDP 59,147 2.80 % AFRICAN CONGRESS OF DEMOCRATS A.C.D 402 0.02 % AFRICAN CONTENT MOVEMENT ACM 186 0.01 % AFRICAN COVENANT ACO 1,101 0.05 % AFRICAN DEMOCRATIC CHANGE ADEC 553 0.03 % AFRICAN INDEPENDENT CONGRESS AIC 3,133 0.15 % AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS ANC 659,548 31.23 % AFRICAN PEOPLE'S CONVENTION APC 1,001 0.05 % AFRICAN RENAISSANCE UNITY ARU 210 0.01 % AFRICAN SECURITY CONGRESS ASC 1,599 0.08 % AFRICAN TRANSFORMATION MOVEMENT ATM 4,761 0.23 % AFRIKAN ALLIANCE OF SOCIAL DEMOCRATS AASD 696 0.03 % AGANG SOUTH AFRICA AGANG SA 767 0.04 % AL JAMA-AH ALJAMA 15,866 0.75 % ALLIANCE FOR TRANSFORMATION FOR ALL ATA 5,378 0.25 % AZANIAN PEOPLE'S ORGANISATION AZAPO 559 0.03 % BETTER RESIDENTS ASSOCIATION BRA 279 0.01 % BLACK FIRST LAND FIRST BLF 857 0.04 % CAPITALIST PARTY OF SOUTH AFRICA ZACP 3,822 0.18 % CHRISTIAN POLITICAL MOVEMENT CPM 866 0.04 % COMPATRIOTS OF SOUTH AFRICA CSA 608 0.03 % CONGRESS OF THE PEOPLE COPE 9,726 0.46 % DEMOCRATIC ALLIANCE DA 1,107,065 52.41 % DEMOCRATIC LIBERAL CONGRESS DLC 805 0.04 % ECONOMIC EMANCIPATION FORUM ECOFORU 344 0.02 % M ECONOMIC FREEDOM FIGHTERS EFF 88,428 4.19 % FORUM 4 SERVICE DELIVERY F4SD 271 0.01 % Page 1 of 2 Results Reports Detailed Results Results as at: 13/05/2019 04:22:28 PM Electoral Event: 2019 NATIONAL ELECTION Province: Western Cape Municipality: All Municipalities Party Name Abbr. -

Results Reports

Results Reports Detailed Results Results as at: 24/07/2019 03:08:01 PM Electoral Event: 2019 NATIONAL ELECTION Province: Gauteng Municipality: All Municipalities Registered Population: 6,381,220 Party Name Abbr. No. of Votes % Votes AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY ACDP 36,249 0.80 % AFRICAN CONGRESS OF DEMOCRATS A.C.D 918 0.02 % AFRICAN CONTENT MOVEMENT ACM 1,174 0.03 % AFRICAN COVENANT ACO 2,782 0.06 % AFRICAN DEMOCRATIC CHANGE ADEC 992 0.02 % AFRICAN INDEPENDENT CONGRESS AIC 9,715 0.21 % AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS ANC 2,413,979 53.20 % AFRICAN PEOPLE'S CONVENTION APC 3,136 0.07 % AFRICAN RENAISSANCE UNITY ARU 900 0.02 % AFRICAN SECURITY CONGRESS ASC 4,225 0.09 % AFRICAN TRANSFORMATION MOVEMENT ATM 9,948 0.22 % AFRIKAN ALLIANCE OF SOCIAL DEMOCRATS AASD 2,486 0.05 % AGANG SOUTH AFRICA AGANG SA 2,579 0.06 % AL JAMA-AH ALJAMA 7,064 0.16 % ALLIANCE FOR TRANSFORMATION FOR ALL ATA 1,345 0.03 % AZANIAN PEOPLE'S ORGANISATION AZAPO 3,842 0.08 % BETTER RESIDENTS ASSOCIATION BRA 565 0.01 % BLACK FIRST LAND FIRST BLF 7,009 0.15 % CAPITALIST PARTY OF SOUTH AFRICA ZACP 7,515 0.17 % CHRISTIAN POLITICAL MOVEMENT CPM 1,248 0.03 % COMPATRIOTS OF SOUTH AFRICA CSA 361 0.01 % CONGRESS OF THE PEOPLE COPE 12,358 0.27 % DEMOCRATIC ALLIANCE DA 1,112,990 24.53 % DEMOCRATIC LIBERAL CONGRESS DLC 854 0.02 % ECONOMIC EMANCIPATION FORUM ECOFORU 1,398 0.03 % M ECONOMIC FREEDOM FIGHTERS EFF 613,704 13.53 % FORUM 4 SERVICE DELIVERY F4SD 729 0.02 % Page 1 of 2 Results Reports Detailed Results Results as at: 24/07/2019 03:08:01 PM Electoral Event: 2019 NATIONAL ELECTION Province: Gauteng Municipality: All Municipalities Party Name Abbr. -

2019 GENERAL ELECTIONS in SOUTH AFRICA Political Parties

2019 GENERAL ELECTIONS IN SOUTH AFRICA Political Parties Contesting the 2019 Elections Residents cast their votes during the Nquthu by-election at Springlake High School on May 24, 2017 in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. (Photo by Gallo Images / The Times / Thuli Dlamini) The IEC announced that a record 48 political parties have successfully registered to contest the 2019 general elections. Most have been formed recently, suggesting that many see an opportunity to capitalise on voter uncertainty after the Zuma years. Noteworthy, too, is the number of religious parties — with churches hoping to turn congregant numbers into political power. In the first of a two-part series, we take a brief look at the parties appearing on the ballot sheet in May. African Christian Democratic Party Launched in 1993, one of the ACDP’s unique claims to fame is that it was the only party to reject the South African Constitution — on the basis that it enshrined the right to abortion. Supports a return to “biblical principles”, including the imposition of the death penalty. Led by Dr Kenneth Meshoe, the ACDP received just over 104,000 votes nationally in the 2014 elections, giving it three seats in the National Assembly. African Congress of Democrats No information is available. Confusingly, there is a Namibian opposition party of the same name; and the South African Congress of Democrats was an anti-apartheid organisation run by radical white lefties. African Content Movement The ACM was launched in December 2018 by former SABC chief operations officer Hlaudi Motsoeneng. As per the party’s name, which refers to Motsoeneng’s policy of promoting local content at the SABC, the party will have a special focus on protecting creative artists. -

South African Federalism

Eyrice Tepeciklioglu, E. / Journal of Yasar University, 2018, 13/50, 164-175 South African Federalism: Constitution-Making Process and the Decline of the Federalism Debate1 Güney Afrika Federalizmi: Anayasa Yapım Süreci ve Federalizm Tartışmasının Güncelliğini Yitirmesi Elem EYRICE TEPECIKLIOGLU, Yasar University, Turkey, [email protected] Abstract: The 1990s heralded the beginning of a historical period in South African politics with the signing of the National Peace Accord, the unbanning of black opposition movements, the release of political prisoners and, most importantly, the end of the apartheid regime. Negotiations between major political groups of the country produced the Interim Constitution of 1993 approved by the Multi-Party Negotiating Council, which resulted in the country’s first democratic and multi-racial elections in 1994. The current 1996 constitution was prepared during the transition period in line with the Constitutional Principles of the Interim Constitution. This article argues that federal principles entrenched both in the Interim Constitution and Final Constitution played a key role in the transition to democracy and contributed to the success of negotiations. However, South Africa’s (quasi) federal system is now highly centralized with decreasing autonomy of its constituent units. This article will first provide an analysis on how federal principles became the major bargaining tool of the constitutional negotiations before proceeding with an examination of the very reasons behind the demise of the federalism debate in South African politics. Keywords: South Africa, South African Politics, Constitutional Negotiations, Federalism Öz: Ulusal Barış Anlaşması’nın imzalandığı, siyasi yasakların kaldırıldığı, siyasi suçluların serbest bırakıldığı ve hepsinden önemlisi, ırk ayrımına dayanan rejimin (apartheid) ortadan kalktığı 1990’lı yıllar Güney Afrika siyasetinde tarihi bir dönemi müjdelemekteydi.