Air Transport Association 2008 Economic Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 of 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 OF 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report AGREEMENT : Standard PERIOD: P01 September 2021 MEMBER CODE MEMBER NAME ZONE STATUS CATEGORY XB-B72 "INTERAVIA" LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY B Live Associate Member FV-195 "ROSSIYA AIRLINES" JSC D Live IATA Airline 2I-681 21 AIR LLC C Live ACH XD-A39 617436 BC LTD DBA FREIGHTLINK EXPRESS C Live ACH 4O-837 ABC AEROLINEAS S.A. DE C.V. B Suspended Non-IATA Airline M3-549 ABSA - AEROLINHAS BRASILEIRAS S.A. C Live ACH XB-B11 ACCELYA AMERICA B Live Associate Member XB-B81 ACCELYA FRANCE S.A.S D Live Associate Member XB-B05 ACCELYA MIDDLE EAST FZE B Live Associate Member XB-B40 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS AMERICAS INC B Live Associate Member XB-B52 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS INDIA LTD. D Live Associate Member XB-B28 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B70 ACCELYA UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B86 ACCELYA WORLD, S.L.U D Live Associate Member 9B-450 ACCESRAIL AND PARTNER RAILWAYS D Live Associate Member XB-280 ACCOUNTING CENTRE OF CHINA AVIATION B Live Associate Member XB-M30 ACNA D Live Associate Member XB-B31 ADB SAFEGATE AIRPORT SYSTEMS UK LTD. A Live Associate Member JP-165 ADRIA AIRWAYS D.O.O. D Suspended Non-IATA Airline A3-390 AEGEAN AIRLINES S.A. D Live IATA Airline KH-687 AEKO KULA LLC C Live ACH EI-053 AER LINGUS LIMITED B Live IATA Airline XB-B74 AERCAP HOLDINGS NV B Live Associate Member 7T-144 AERO EXPRESS DEL ECUADOR - TRANS AM B Live Non-IATA Airline XB-B13 AERO INDUSTRIAL SALES COMPANY B Live Associate Member P5-845 AERO REPUBLICA S.A. -

Here Applicants and Recruiters Can • Read All the Magazine Issues of Aero Crew News

September 2016 Aero Crew News Your Source for Pilot Hiring Information and More... Contract Talks Moving Benefits Exclusive Hiring Briefing Aviator Bulletins Upgraded Training Facilities, Partnerships with Schools CPP, internship and more! Fitness Corner Calories in Your Drink, Beware You deserve your dream job. ExpressJet o ers everything that you’re looking for when starting your career. Make the smart choice for your future and fly with the best at ExpressJet. Great Pay o $37-40/hr first year pay o Guaranteed profit sharing program o Leading healthcare benefits Path to the Majors o United Career Path Program o JetBlue University and Advanced Gateways o More pilots hired by the majors each year than any other regional Industry-leading Training o ATP CTP o ered for free (always!) as part of paid training o In-house training tailored to each pilot gives you the best rate of success o Advanced Qualification Program (AQP) Learn more about why ExpressJet is the smart choice for your future at flysmartchoice.com Apply today at expressjet.com/apply You deserve your dream job. ExpressJet o ers everything that you’re looking for when starting your career. Make the smart choice for your future and fly with the best at ExpressJet. Great Pay o $37-40/hr first year pay o Guaranteed profit sharing program Aero Crew Solutions Launches New Website Aero Crew Solutions is proud to announce the complete • The ability for companies to publish their latest o Leading healthcare benefits redesign of our website. Our goal is to continue the job news on our website. -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Appendix 25 Box 31/3 Airline Codes

March 2021 APPENDIX 25 BOX 31/3 AIRLINE CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 000 ANTONOV DESIGN BUREAU 001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 005 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES 006 DELTA AIR LINES 012 NORTHWEST AIRLINES 014 AIR CANADA 015 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES 016 UNITED AIRLINES 018 CANADIAN AIRLINES INT 020 LUFTHANSA 023 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORP. (CARGO) 027 ALASKA AIRLINES 029 LINEAS AER DEL CARIBE (CARGO) 034 MILLON AIR (CARGO) 037 USAIR 042 VARIG BRAZILIAN AIRLINES 043 DRAGONAIR 044 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 045 LAN-CHILE 046 LAV LINEA AERO VENEZOLANA 047 TAP AIR PORTUGAL 048 CYPRUS AIRWAYS 049 CRUZEIRO DO SUL 050 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 051 LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO 053 AER LINGUS 055 ALITALIA 056 CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES 057 AIR FRANCE 058 INDIAN AIRLINES 060 FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES 061 AIR SEYCHELLES 062 DAN-AIR SERVICES 063 AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 064 CSA CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES 065 SAUDI ARABIAN 066 NORONTAIR 067 AIR MOOREA 068 LAM-LINHAS AEREAS MOCAMBIQUE Page 2 of 19 Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 069 LAPA 070 SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES 071 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 072 GULF AIR 073 IRAQI AIRWAYS 074 KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES 075 IBERIA 076 MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES 077 EGYPTAIR 078 AERO CALIFORNIA 079 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 080 LOT POLISH AIRLINES 081 QANTAS AIRWAYS -

Nevada-California, USA November 2014

Nevada-California, USA November 2014 While the end of 2014 was approaching, I still had about ten vacation days left. Therefore I decided to spent these on a spotting trip. I teamed up with fellow reader EC and we agreed that the south-western part of the United States would be a great place to visit. The chances of finding nice airplanes and good weather in this part of the world are rather high, even at the end of November. We decided to spend three days in Las Vegas and then drive to southern California, where we would spend almost a full week. The primary focus would be on photographing airliners and fire fighting aircraft, but some number crunching was done as well (although most logs below are not complete). Please note that all mm’s mentioned apply to a 1.5 crop factor camera and all aircraft are only noted once per airport. On the morning of Wednesday 19 November Eddy and I met at Schiphol at approximately 8 AM. There we learned that our flight to Houston was delayed for several hours. Fortunately United Airlines rebooked us on flight UA908 to Chicago. 19 November 2014 Schiphol EHAM G-FBEI Embraer 195LR Flybe LZ-FBE Airbus A320-200 Bulgaria Air N14121 Boeing 757-200 United Airlines N652UA Boeing 767-300ER United Airlines YU-APJ Airbus A319-100 Air Serbia A few planes were noted before boarding the 22-year-old Boeing 767. The flight to Chicago was uneventful in my opinion. However some other passengers complained about the cabin temperature and as a result all passengers received an 100 USD online voucher, to be spent on United Airlines flights with in the next year. -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

Traffic Report

TRAFFIC REPORT PALM BEACH INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT PERIOD ENDED NOVEMBER 2008 2008/Nov 2007/Nov Percent Change 12 Months 12 Months Percent Change Ended Ended November 2008 November 2007 Total Passengers 493,852 561,053 -11.98% 6,521,590 6,955,356 -6.24% Total Cargo Tons * 1,048.7 1,456.6 -28.00% 15,584.7 16,083.5 -3.10% Landed Weight (Thousands of Lbs.) 326,077 357,284 -8.73% 4,106,354 4,370,930 -6.05% Air Carrier Operations** 5,099 5,857 -12.94% 67,831 72,125 -5.95% GA & Other Operations*** 8,313 10,355 -19.72% 107,861 118,145 -8.70% Total Operations 13,412 16,212 -17.27% 175,692 190,270 -7.66% H17 + H18 + H19 + H20 13,412.0000 16,212.0000 -17.27% 175,692.0000 190,270.0000 -7.66% * Freight plus mail reported in US tons. ** Landings plus takeoffs. *** Per FAA Tower. PALM BEACH COUNTY - DEPARTMENT OF AIRPORTS 846 Palm Beach Int'l. Airport, West Palm Beach, FL 33406-1470 or visit our web site at www.pbia.org TRAFFIC REPORT PALM BEACH INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT AIRLINE PERCENTAGE OF MARKET November 2008 2008/Nov 12 Months Ended November 2008 Enplaned Market Share Enplaned Market Share Passengers Passengers Total Enplaned Passengers 246,559 100.00% 3,273,182 100.00% Delta Air Lines, Inc. 54,043 21.92% 676,064 20.65% JetBlue Airways 50,365 20.43% 597,897 18.27% US Airways, Inc. 36,864 14.95% 470,538 14.38% Continental Airlines, Inc. -

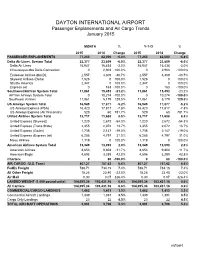

DAYTON INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT Passenger Enplanements and Air Cargo Trends January 2015

DAYTON INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT Passenger Enplanements and Air Cargo Trends January 2015 MONTH % Y-T-D % 2015 2014 Change 2015 2014 Change PASSENGER ENPLANEMENTS 77,253 82,000 -5.8% 77,253 82,000 -5.8% Delta Air Lines, System Total 22,377 23,809 -6.0% 22,377 23,809 -6.0% Delta Air Lines 15,947 16,434 -3.0% 15,947 16,434 -3.0% Chautauqua dba Delta Connection 0 2,903 -100.0% 0 2,903 -100.0% Endeavor Airlines dba DL 2,557 4,309 -40.7% 2,557 4,309 -40.7% Skywest Airlines (Delta) 1,526 0 100.0% 1,526 0 100.0% Shuttle America 2,347 0 100.0% 2,347 0 100.0% Express Jet 0 163 -100.0% 0 163 -100.0% Southwest/AirTran System Total 11,861 15,453 -23.2% 11,861 15,453 -23.2% AirTran Airways System Total 0 10,274 -100.0% 0 10,274 -100.0% Southwest Airlines 11,861 5,179 129.0% 11,861 5,179 129.0% US Airways System Total 16,949 17,877 -5.2% 16,949 17,877 -5.2% US Airways Express (PSA) 16,420 17,817 -7.8% 16,420 17,817 -7.8% US Airways Express (Air Wsconsin) 529 60 781.7% 529 60 781.7% United Airlines System Total 12,717 11,688 8.8% 12,717 11,688 8.8% United Express (Skywest) 1,220 2,672 -54.3% 1,220 2,672 -54.3% United Express (Trans State) 2,355 2,072 13.7% 2,355 2,072 13.7% United Express (GoJet) 1,738 2,147 -19.0% 1,738 2,147 -19.0% United Express (Express Jet) 6,285 4,797 31.0% 6,285 4,797 31.0% Mesa Airlines 1,119 0 100.0% 1,119 0 100.0% American Airlines System Total 13,349 13,093 2.0% 13,349 13,093 2.0% American Airlines 8,653 9,804 -11.7% 8,653 9,804 -11.7% American Eagle 4,696 3,289 42.8% 4,696 3,289 42.8% Charters 0 80 -100.0% 0 80 -100.0% AIR CARGO (U.S. -

Miami-Dade Aviation Department

Miami-Dade Aviation Department Aviation Statistics Freight Carried - All Airlines Facility: MIA Units: Short Tons Current Year: 10/2008 - 09/2009 Prior Year:10/2007 - 09/2008 Domestic International Total % Total Domestic International Arrival Departure Arrival Departure Freight Change Operator Freight Arrival Departure Arrival Departure 1,072.71 576.85 102,274.77 82,085.54 186,009.87 4.70% Arrow Air Inc dba Arrow Cargo 177,658.38 176.02 24.64 90,907.92 86,549.80 0.00 0.00 88,469.11 80,646.07 169,115.18 -19.72% LAN Airlines f/k/a LAN Chile SA 210,661.41 0.00 0.00 108,679.01 101,982.40 16,930.09 10,610.21 66,304.74 52,151.21 145,996.25 -13.02% United Parcel Service 167,841.52 18,554.52 13,794.09 75,516.57 59,976.34 0.00 0.00 74,171.56 59,663.09 133,834.65 -16.64% Tampa Cargo S.A. fka Tampa 160,545.15 0.00 0.00 85,662.87 74,882.28 Airlines 92.00 92.00 70,159.66 59,667.03 130,010.69 -26.35% Centurion Air Cargo 176,520.00 190.00 190.00 92,027.00 84,113.00 19,053.20 18,085.60 47,488.80 31,104.70 115,732.30 -24.58% American Airlines Inc 153,450.50 24,095.50 28,221.40 64,487.20 36,646.40 54,637.00 45,007.83 0.00 290.00 99,934.83 -9.93% Federal Express Corporation 110,952.56 64,973.52 45,661.52 0.00 317.52 10,005.77 7,325.30 28,235.37 37,789.61 83,356.05 30.42% ABX Air 63,912.36 304.01 684.77 28,837.23 34,086.35 0.00 0.00 29,650.30 37,691.47 67,341.77 -14.12% Amerijet International 78,411.69 0.00 0.00 29,877.59 48,534.10 813.27 732.46 35,167.78 21,852.19 58,565.70 -32.36% Southern Air Inc 86,581.41 0.00 0.00 49,197.13 37,384.28 1,219.03 60.08 28,053.94 20,361.20 49,694.25 22.68% Atlas Air Inc 40,507.95 9,678.58 1,175.01 16,043.06 13,611.30 42.35 42.35 24,096.30 19,103.37 43,284.37 -39.15% Cielos Del Peru SA 71,135.13 0.00 0.00 39,146.51 31,988.62 3,027.07 886.64 18,678.17 17,239.72 39,831.60 -36.46% Florida West International Airways 62,687.03 3,077.66 2,773.66 29,842.93 26,992.78 0.00 0.00 17,874.13 14,802.81 32,676.94 100.00% Linea Aerea Carguera de Colombia 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 S.A. -

Air Transport Association of America

June 12, 2008 Carl Povilaitis, President Burbank-Glendale-Pasadena Airport Authority Dan Feger, Interim Executive Director Burbank-Glendale-Pasadena Airport Part 161 Study Comment Docket Burbank-Glendale-Pasadena Airport Authority Bob Hope Airport 2627 Hollywood Way Burbank, CA 91505 Fax: (818) 840-0651 Dear Messrs. Povilaitis and Feger: On behalf of the airline members of the Air Transport Association of America, Inc. (ATA),1 we offer the following comments on the Burbank-Glendale-Pasadena Airport Authority’s proposed curfew applicable to Stage 3 aircraft operations at Bob Hope Airport (BUR). These comments are based on the application prepared pursuant to Federal Aviation Regulation 161.303 and the Airport Noise and Capacity Act of 1990 (ANCA) and the supporting analysis prepared by the Airport Authority’s consultants (“Part 161 Analysis”).2 As the first application for a Stage 3 restriction under ANCA, 1 ATA is the principal trade and service organization of the major scheduled air carriers in the United States. ATA airline members are: ABX Air, Inc.; AirTran Airways; Alaska Airlines, Inc.; American Airlines, Inc.; ASTAR Air Cargo, Inc.; Atlas Air, Inc.; Continental Airlines, Inc.; Delta Air Lines, Inc.; Evergreen International Airlines, Inc.; Federal Express Corporation; Hawaiian Airlines; JetBlue Airways Corp.; Midwest Airlines, Inc.; Northwest Airlines, Inc.; Southwest Airlines Co.; United Airlines, Inc.; UPS Airlines; and US Airways, Inc. ATA Airline Associate Members are: Air Canada, Air Jamaica Ltd. and Mexicana. 2 Jacobs Consultancy, Official Draft, FAR Part 161 Application for a Proposed Curfew, Bob Hope Airport (March 2008). this proposal merits close scrutiny and must be viewed in light of the precedents it may set for other airports. -

Greater Orlando Aviation Authority

Greater Orlando Aviation Authority - Orlando International Airport Landed Weight Statistics For Period OCT-2019 through SEP-2020 Domestic International Airline Name Revenue Non-Revenue Revenue Non-Revenue Total 21 Air, LLC 22,357 22,357 ABC Aerolineas SA de CV 26,771 26,771 ABX Air Inc 3,158 3,158 Aer Lingus Ltd 34,373 34,373 Aerolineas Argentinas S.A. Inc. 16,362 16,362 Aerovias Del Continente Americano-Avianca 38,286 38,286 Pre-Bank Aerovias de Mexico SA de CV 8,192 8,192 Aerovias de Mexico SA de CV Pre- 38,193 38,193 Bankruptcy Air Canada 283,213 283,213 Air Transat A.T. Inc. 27,411 27,411 Alaska Airlines Inc 196,122 196,122 American Airlines Inc 2,187,113 2,187,113 Amerijet International, Inc. 64,184 64,184 Atlas Air Inc. 49,185 6,342 55,527 Azul Linhas Aereas Brasileiras S.A. Inc 142,783 142,783 Bahamasair Holdings Limited, Inc 23,245 23,245 British Airways 90,930 90,930 Caribbean Airlines Limited 11,996 11,996 Concesionaria Vuela Compania Aviacion 23,548 23,548 SAPI de CV Copa Airlines 117,871 117,871 Delta Air Lines 2,188,785 45,992 2,234,777 Eastern Airlines, LLC 278 278 Edelweiss Air AG 1,649 1,649 Emirates Inc 17,174 70,234 87,408 Fast Colombia S.A.S. 284 284 Federal Express Corporation 360,287 360,287 Frontier Airlines 1,696,675 3,246 1,699,921 GOL Linhas Aereas S.A. 33,064 33,064 Hi Fly, Ltd 1,737 1,737 Hi Fly, Transportes Aereos SA 401 401 Icelandair, LLC 28,046 28,046 JetBlue Airways Corp. -

Annual Report 2007

EU_ENTWURF_08:00_ENTWURF_01 01.04.2026 13:07 Uhr Seite 1 Analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 EUROPEAN COMMISSION EU_ENTWURF_08:00_ENTWURF_01 01.04.2026 13:07 Uhr Seite 2 Air Transport and Airport Research Annual analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 German Aerospace Center Deutsches Zentrum German Aerospace für Luft- und Raumfahrt e.V. Center in the Helmholtz-Association Air Transport and Airport Research December 2008 Linder Hoehe 51147 Cologne Germany Head: Prof. Dr. Johannes Reichmuth Authors: Erik Grunewald, Amir Ayazkhani, Dr. Peter Berster, Gregor Bischoff, Prof. Dr. Hansjochen Ehmer, Dr. Marc Gelhausen, Wolfgang Grimme, Michael Hepting, Hermann Keimel, Petra Kokus, Dr. Peter Meincke, Holger Pabst, Dr. Janina Scheelhaase web: http://www.dlr.de/fw Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02 Release: 2.2 Page 1 Annual analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 Document Control Information Responsible project manager: DG Energy and Transport Project task: Annual analyses of the European air transport market 2007 EC contract number: TREN/05/MD/S07.74176 Release: 2.2 Save date: 2008-12-02 Total pages: 222 Change Log Release Date Changed Pages or Chapters Comments 1.2 2008-06-20 Final Report 2.0 2008-10-10 chapters 1,2,3 Final Report - full year 2007 draft 2.1 2008-11-20 chapters 1,2,3,5 Final updated Report 2.2 2008-12-02 all Layout items Disclaimer and copyright: This report has been carried out for the Directorate-General for Energy and Transport in the European Commission and expresses the opinion of the organisation undertaking the contract TREN/05/MD/S07.74176.