Iraq War Films: Defining a Subgenre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DAN LEIGH Production Designer

(3/31/17) DAN LEIGH Production Designer FILM & TELEVISION DIRECTOR COMPANIES PRODUCERS “GYPSY” Sam Taylor-Johnson Netflix Rudd Simmons (TV Series) Scott Winant Universal Television Tim Bevan “THE FAMILY” Paul McGuigan ABC David Hoberman (Pilot / Series) Mandeville Todd Lieberman “FALLING WATER” Juan Carlos Fresnadillo USA Gale Anne Hurd (Pilot) Valhalla Entertainment Blake Masters “THE SLAP” Lisa Cholodenko NBC Rudd Simmons (TV Series) Michael Morris Universal Television Ken Olin “THE OUTCASTS” Peter Hutchings BCDF Pictures Brice Dal Farra Claude Dal Farra “JOHN WICK” David Leitch Thunder Road Pictures Basil Iwanyk Chad Stahelski “TRACERS” Daniel Benmayor Temple Hill Entertainment Wyck Godfrey FilmNation Entertainment D. Scott Lumpkin “THE AMERICANS” Gavin O'Connor DreamWorks Television Graham Yost (Pilot) Darryl Frank “VAMPS” Amy Heckerling Red Hour Adam Brightman Lucky Monkey Stuart Cornfeld Molly Hassell Lauren Versel “PERSON OF INTEREST” Various Bad Robot J.J. Abrams (TV Series) CBS Johanthan Nolan Bryan Burk Margot Lulick “WARRIOR” Gavin O’Connor Lionsgate Greg O’Connor Solaris “MARGARET” Kenneth Lonergan Mirage Enterprises Gary Gilbert Fox Searchlight Sydney Pollack Scott Rudin “BRIDE WARS” Gary Winick Firm Films Alan Riche New Regency Pictures Peter Riche Julie Yorn “THE BURNING PLAIN” Guillermo Arriaga 2929 Entertainment Laurie MacDonald Walter F. Parkes SANDRA MARSH & ASSOCIATES Tel: (310) 285-0303 Fax: (310) 285-0218 e-mail: [email protected] (3/31/17) DAN LEIGH Production Designer ---2-222---- FILM & TELEVISION COMPANIES -

2009 Sundance Film Festival Announces Films in Competition

Media Contacts: For Immediate Release Brooks Addicott, 435.658.3456 December 3, 2008 [email protected] Amy McGee, 310.492.2333 [email protected] 2009 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES FILMS IN COMPETITION Festival Celebrates 25 Years of Independent Filmmaking and Cinematic Storytelling Park City, UT—Sundance Institute announced today the lineup of films selected to screen in the U.S. and World Cinema Dramatic and Documentary Competitions for the 25th Sundance Film Festival. In addition to the four Competition categories, the Festival presents films in five out-of-competition sections to be announced tomorrow. The 2009 Sundance Film Festival runs January 15-25 in Park City, Salt Lake City, Ogden, and Sundance, Utah. The complete list of films is available at www.sundance.org/festival. "This year's films are not narrowly defined. Instead we have a blurring of genres, a crossing of boundaries: geographic, generational, socio-economic and the like," said Geoffrey Gilmore, Director, Sundance Film Festival. "The result is both an exhilarating and emotive Festival in which traditional mythologies are suspended, discoveries are made, and creative storytelling is embraced." "Audiences may be surprised by how much emotion this year's films evoke," said John Cooper, Director of Programming, Sundance Film Festival. "We are seeing the next evolution of the independent film movement where films focus on storytelling with a sense of connection and purpose." For the 2009 Sundance Film Festival, 118 feature-length films were selected including 88 world premieres, 18 North American premieres, and 4 U.S. premieres representing 21 countries with 42 first-time filmmakers, including 28 in competition. -

The Chichester Festival Theatre Productions YOUNG CHEKHOV

The Chichester Festival Theatre productions YOUNG CHEKHOV Olivier Theatre Previews from 14 July, press day 3 August, booking until 3 September with further performances to be announced. The YOUNG CHEKHOV trilogy opened to overwhelming acclaim at Chichester Festival Theatre last year. The company now come to the National, offering a unique chance to explore the birth of a revolutionary dramatic voice. The production is directed by Jonathan Kent, with set designs by Tom Pye, costumes by Emma Ryott, lighting by Mark Henderson, music by Jonathan Dove, sound by Paul Groothuis and fight direction by Paul Benzing. Performed by one ensemble of actors, each play can be seen as a single performance over different days or as a thrilling all-day theatrical experience. Cast includes Emma Amos, Pip Carter, Anna Chancellor, Jonathan Coy, Mark Donald, Peter Egan, Col Farrell, Beverley Klein, Adrian Lukis, Des McAleer, James McArdle, Mark Penfold, Nina Sosanya, Geoffrey Streatfeild, Sarah Twomey, David Verrey, Olivia Vinall and Jade Williams. David Hare has written over thirty original plays, including The Power of Yes, Gethsemane, Stuff Happens, The Permanent Way (a co-production with Out of Joint), Amy’s View, Skylight, The Secret Rapture, The Absence of War, Murmuring Judges, Racing Demon, Pravda (written with Howard Brenton) and Plenty for the National Theatre. His other work includes South Downs (Chichester Festival Theatre and West End), The Judas Kiss (Hampstead and West End) and The Moderate Soprano (Hampstead). His adaptations include Behind the Beautiful Forevers and The House of Bernarda Alba at the NT, The Blue Room (Donmar and Broadway) and The Master Builder (The Old Vic). -

The Humanitarian Impact of Drones

THE HUMANITARIAN IMPACT OF DRONES The Humanitarian Impact of Drones 1 THE HUMANITARIAN IMPACT OF DRONES THE HUMANITARIAN IMPACT OF DRONES © 2017 Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom; International Contents Disarmament Institute, Pace University; Article 36. October 2017 The Humanitarian Impact of Drones 1st edition 160 pp 3 Preface Permission is granted for non-commercial reproduction, Cristof Heyns copying, distribution, and transmission of this publication or parts thereof so long as full credit is given to the 6 Introduction organisation and author; the text is not altered, Ray Acheson, Matthew Bolton, transformed, or built upon; and for any reuse or distribution, these terms are made clear to others. and Elizabeth Minor Edited by Ray Acheson, Matthew Bolton, Elizabeth Minor, and Allison Pytlak. Impacts Thank you to all authors for their contributions. 1. Humanitarian Harm This publication is supported in part by a grant from the 15 Foundation Open Society Institute in cooperation with the Jessica Purkiss and Jack Serle Human Rights Initiative of the Open Society Foundations. Cover photography: 24 Country case study: Yemen ©2017 Kristie L. Kulp Taha Yaseen 29 2. Environmental Harm Doug Weir and Elizabeth Minor 35 Country case study: Nigeria Joy Onyesoh 36 3. Psychological Harm Radidja Nemar 48 4. Harm to Global Peace and Security Chris Cole 58 Country case study: Djibouti Ray Acheson 64 Country case study: The Philippines Mitzi Austero and Alfredo Ferrariz Lubang 2 1 THE HUMANITARIAN IMPACT OF DRONES Preface Christof Heyns 68 5. Harm to Governmental It is not difficult to understand the appeal of Transparency Christof Heyns is Professor of Law at the armed drones to those engaged in war and other University of Pretoria. -

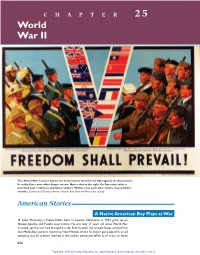

C H a P T E R 25 World War II

NASH.7654.CP25p826-861.vpdf 9/23/05 3:35 PM Page 826 CHAPTER 25 World War II This World War II poster depicts the many nations united in the fight against the Axis powers. In reality there were often disagreements. Notice that to the right, the American sailor is marching next to Chinese and Soviet soldiers. Within a few years after victory, they would be enemies. (University of Georgia Libraries, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library) American Stories A Native American Boy Plays at War N. Scott Momaday, a Kiowa Indian born in Lawton, Oklahoma, in 1934, grew up on Navajo,Apache, and Pueblo reservations. He was only 11 years old when World War II ended, yet the war had changed his life. Shortly after the United States entered the war, Momaday’s parents moved to New Mexico, where his father got a job with an oil company and his mother worked in the civilian personnel office at an army air force 826 NASH.7654.CP25p826-861.vpdf 9/23/05 3:35 PM Page 827 CHAPTER OUTLINE base. Like many couples, they had struggled through the hard times of the Depression. The Twisting Road to War The war meant jobs. Foreign Policy in a Global Age Momaday’s best friend was Billy Don Johnson, a “reddish, robust boy of great good Europe on the Brink of War humor and intense loyalty.” Together they played war, digging trenches and dragging Ethiopia and Spain themselves through imaginary minefields. They hurled grenades and fired endless War in Europe rounds from their imaginary machine guns, pausing only to drink Kool-Aid from their The Election of 1940 canteens.At school, they were taught history and math and also how to hate the enemy Lend-Lease and be proud of America. -

Native Americans and World War II

Reemergence of the “Vanishing Americans” - Native Americans and World War II “War Department officials maintained that if the entire population had enlisted in the same proportion as Indians, the response would have rendered Selective Service unnecessary.” – Lt. Col. Thomas D. Morgan Overview During World War II, all Americans banded together to help defeat the Axis powers. In this lesson, students will learn about the various contributions and sacrifices made by Native Americans during and after World War II. After learning the Native American response to the attack on Pearl Harbor via a PowerPoint centered discussion, students will complete a jigsaw activity where they learn about various aspects of the Native American experience during and after the war. The lesson culminates with students creating a commemorative currency honoring the contributions and sacrifices of Native Americans during and after World War II. Grade 11 NC Essential Standards for American History II • AH2.H.3.2 - Explain how environmental, cultural and economic factors influenced the patterns of migration and settlement within the United States since the end of Reconstruction • AH2.H.3.3 - Explain the roles of various racial and ethnic groups in settlement and expansion since Reconstruction and the consequences for those groups • AH2.H.4.1 - Analyze the political issues and conflicts that impacted the United States since Reconstruction and the compromises that resulted • AH2.H.7.1 - Explain the impact of wars on American politics since Reconstruction • AH2.H.7.3 - Explain the impact of wars on American society and culture since Reconstruction • AH2.H.8.3 - Evaluate the extent to which a variety of groups and individuals have had opportunity to attain their perception of the “American Dream” since Reconstruction Materials • Cracking the Code handout, attached (p. -

FILMOGRAFIA (A Cura Di Bear EAF51 – Aggiornamento Luglio 2020)

FILMOGRAFIA (a cura di Bear_EAF51 – Aggiornamento Luglio 2020) Quello che segue è un puro elenco, per argomento ed in ordine alfabetico, di film di argomento bellico o aeronautico. Non si tratta quindi di vere e proprie recensioni: questa filmografia nasce con l’intento di fornire una sorta di orientamento agli interessati. Molti dei film sono reperibili in rete (streaming o download) o in DVD. Alcuni sono disponibili solo in lingua originale. Altri ancora sono purtroppo introvabili perché esauriti da tempo. Per ogni film ho cercato di indicare il titolo in Italiano, il titolo originale, l’anno di realizzazione, e una breve descrizione del contenuto o della trama. Ho classificato i titoli in ordine alfabetico. Se il titolo inizia con un articolo l’ordine alfabetico non ne tiene conto, e considera la prima parola dopo l’articolo (esempio: “I lunghi giorni delle Aquile” è catalogato come “Lunghi Giorni delle Aquile”. L’articolo è anteposto al titolo, tra parentesi) Per rendere più facile la consultazione per genere, ho diviso i titoli in nove sezioni: 1. Aerei, Prima e Seconda guerra mondiale 2. Aerei, Post WW2 & Jets 3. Aerei o quasi (altri film dove l’aereo in genere è solo di contorno) 4. Techno-Thriller 5. War Movies (Film bellici) 6. Film a sfondo militare 7. Serie TV di guerra o di argomento militare 8. War-Fanta-Horror-Movies (Film horror e fantascientifici a sfondo bellico) 9. Documentari Ho aggiunto anche valutazioni del tutto personali, non per forza condivisibili. Ad ogni film ho attribuito un punteggio, espresso in numero di asterischi con una scala da uno a cinque, che rispecchia esclusivamente quanto il film è piaciuto a me. -

Violence and Masculinity in Hollywood War Films During World War II a Thesis Submitted To

Violence and Masculinity in Hollywood War Films During World War II A thesis submitted to: Lakehead University Faculty of Arts and Sciences Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Master of Arts Matthew Sitter Thunder Bay, Ontario July 2012 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-84504-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-84504-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Film, Politics, and Ideology: Reflections on Hollywood Film in the Age of Reagan* Douglas Kellner (

Film, Politics, and Ideology: Reflections on Hollywood Film in the Age of Reagan* Douglas Kellner (http://www.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/kellner/) In our book Camera Politica: Politics and Ideology in Contemporary Hollywood Film (1988), Michael Ryan and I argue that Hollywood film from the 1960s to the present was closely connected with the political movements and struggles of the epoch. Our narrative maps the rise and decline of 60s radicalism; the failure of liberalism and rise of the New Right in the 1970s; and the triumph and hegemony of the Right in the 1980s. In our interpretation, many 1960s films transcoded the discourses of the anti-war, New Left student movements, as well as the feminist, black power, sexual liberationist, and countercultural movements, producing a new type of socially critical Hollywood film. Films, on this reading, transcode, that is to say, translate, representations, discourses, and myths of everyday life into specifically cinematic terms, as when Easy Rider translates and organizes the images, practices, and discourses of the 1960s counterculture into a cinematic text. Popular films intervene in the political struggles of the day, as when 1960s films advanced the agenda of the New Left and the counterculture. Films of the "New Hollywood," however, such as Bonnie and Clyde, Medium Cool, Easy Rider, etc., were contested by a resurgence of rightwing films during the same era (e.g. Dirty Harry, The French Connection, and any number of John Wayne films), leading us to conclude that Hollywood film, like U.S. society, should be seen as a contested terrain and that films can be interpreted as a struggle of representation over how to construct a social world and everyday life. -

2018 National Theme Announcement

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Wreaths Across America Announces 2018 Theme “Be their witness.” MAINE and Washington, D.C. — Feb. 27, 2018 — Each year, millions of Americans come together to REMEMBER the fallen, HONOR those that serve and their families, and TEACH the next generation about the value of freedom. This gathering of individuals and communities takes place in local and national cemeteries in all 50 states as part of National Wreaths Across America Day. Each year, a new theme is chosen to help supporters focus their messaging and outreach in their own communities. Today, the national nonprofit announces the theme for 2018 is “Be their witness.” The inspiration for this year’s theme stems from the 2009 drama “Taking Chance,” which was based on the experiences of U.S. Marine Lt. Colonel Michael Strobl, who escorted the body of a fallen Marine, PFC Chance Phelps back to his hometown in Wyoming from the Iraq War. “I was deeply impacted by this story and found it difficult at times to fathom the burden this young man carried in his task. Lt. Col. Strobl volunteered to be a witness for PFC Phelps, and as the movie so eloquently states, he is now responsible in no small part for PFC Phelps’s legacy,” said Karen Worcester, executive director, Wreaths Across America. “Through the Wreaths Across America program, we are ensuring that the lives of our men and women in uniform are remembered, not their deaths. It is our responsibility as Americans, to be their witness and to share their stories of service and sacrifice with the next generation.” The millions of volunteers who devote so much of themselves to raise awareness for the mission to Remember, Honor, Teach, in their own communities utilize the annual theme when planning local events and activities in preparation for National Wreaths Across America Day, which will take place this year on Saturday, Dec. -

Of Grandeur and Valour: Bollywood and Indiaís Fighting Personnel 1960-2005

OF GRANDEUR AND VALOUR: BOLLYWOOD AND INDIAíS FIGHTING PERSONNEL 1960-2005 Sunetra Mitra INTRODUCTION Cinema, in Asia and India, can be broadly classified into three categoriesópopular, artistic and experimental. The popular films are commercial by nature, designed to appeal to the vast mass of people and to secure maximum profit. The artistic filmmaker while not abandoning commercial imperatives seeks to explore through willed art facets of indigenous experiences and thought worlds that are amenable to aesthetic treatment. These films are usually designated as high art and get shown at international film festivals. The experimental film directors much smaller in number and much less visible on the film scene are deeply committed to the construction of counter cinema marked by innovativeness in outlook and opposition to the establishment (Dissanayke, 1994: xv-xvi). While keeping these broad generalizations of the main trends in film- making in mind, the paper engages in a discussion of a particular type of popular/ commercial films made in Bollywood1. This again calls for certain qualifications, which better explain the purpose of the paper. The paper attempts to understand Bollywoodís portrayal of the Indian military personnel through a review of films, not necessarily war films but, rather, through a discussion of themes that have war as subject and ones that only mention the military personnel. The films the paper seeks to discuss include Haqeeqat, Border, LOC-Kargil, and Lakshya that has a direct reference to the few wars that India fought in the post-Independence era and also three Bollywood blockbusters namely Aradhana, Veer-Zara and Main Hoon Na, the films that cannot be dubbed as militaristic nor has reference to any war time scenario but nevertheless have substantial reference to the army. -

Sagawkit Acceptancespeechtran

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................