A Study on Minorities in Somalia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

Report on Minority Groups in Somalia

The Danish Immigration Service Ryesgade 53 DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø Phone: + 45 35 36 66 00 Website: www.udlst.dk E-mail: [email protected] Report on minority groups in Somalia Joint British, Danish and Dutch fact-finding mission to Nairobi, Kenya 17 – 24 September 2000 Report on minority groups in Somalia Table of contents 1. Background ..................................................................................................................................5 2. Introduction to sources and methodology....................................................................................6 3. Overall political developments and the security situation in Somalia.......................................10 3.1 Arta peace process in Djibouti...............................................................................................10 3.2 Transitional National Assembly (TNA) and new President ..................................................10 3.2.1 Position of North West Somalia (Somaliland)...............................................................12 3.2.2 Position of North East Somalia (Puntland)....................................................................13 3.2.3 Prospects for a central authority in Somalia ..................................................................13 3.3 Security Situation...................................................................................................................14 3.3.1 General...........................................................................................................................14 -

Somalia OGN V11.0 Issued 27 October 2006

Somalia OGN v11.0 Issued 27 October 2006 OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE NOTE SOMALIA Immigration and Nationality Directorate CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1.1 – 1.4 2. Country assessment 2.1 – 2.15 3. Main categories of claims 3.1 Members of major clan families or related sub-clans 3.6 Bajunis 3.7 Benadiri (Rer Hamar) or Bravanese 3.8 Midgan, Tumal, Yibir or Galgala 3.9 Prison conditions 3.10 4. Discretionary Leave 4.1 Minors claiming in their own right 4.3 Medical treatment 4.4 5. Returns 5.1 – 5.5 6. List of source documents 1. Introduction 1.1 This document summarises the general, political and human rights situation in Somalia and provides information on the nature and handling of claims frequently received from nationals/residents of that country. It must be read in conjunction with any COI Service Somalia Country of Origin Information at: http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/country_reports.html 1.2 This guidance is intended to provide clear guidance on whether the main types of claim are or are not likely to justify the grant of asylum, Humanitarian Protection or Discretionary Leave. Caseworkers should refer to the following Asylum Policy Instructions for further details of the policy on these areas: API on Assessing the Claim API on Humanitarian Protection API on Discretionary Leave API on the European Convention on Human Rights API on Article 8 ECHR 1.3 Claims should be considered on an individual basis, but taking full account of the information set out below, in particular Part 3 on main categories of claims. -

Refugee Status Appeals Authority New Zealand

REFUGEE STATUS APPEALS AUTHORITY NEW ZEALAND REFUGEE APPEAL NO 76551 AT AUCKLAND Before: B L Burson (Member) Counsel for the Appellant: D Ryken Appearing for the Department of Labour: No Appearance Dates of Hearing: 28 & 29 July 2010 Date of Decision: 21 September 2010 DECISION INTRODUCTION [1] This is an appeal against the decision of a refugee status officer of the Refugee Status Branch (RSB) of the Department of Labour (DOL) declining the grant of refugee status to the appellant, a national of Somalia who has spent a number of years in South Africa as a recognised Convention refugee. [2] This is the second time the appellant has appeared before the Authority. He originally arrived in New Zealand in June 2008 and lodged an application for refugee status. He was interviewed by the RSB in respect of that claim on 31 July and 1 August 2008. By decision dated 21 November 2008 the RSB declined the appellant’s claim on the basis that having been recognised as a refugee in South Africa the appellant was entitled to the protection of that country. The appellant duly appealed to the Authority. By decision dated 4 August 2009 the Authority dismissed the appellant’s appeal. [3] On 12 October 2009, the appellant lodged proceedings by way of judicial review in the High Court. By decision dated 4 June 2010 the High Court quashed the decision of the Authority. Although the High Court was satisfied the Authority 2 had not committed any reviewable error itself, the appellant’s previous representative had failed to ensure that a letter from a witness confirming the appellant’s clan origins was not placed before the Authority and the High Court reached the view that the Authority should, as a matter of fairness, re-assess the appellant’s claim having regard to this evidence. -

Issue Paper VICTIMS and VULNERABLE GROUPS in SOUTHERN SOMALIA May 1995

Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/VICTIMS A... Français Home Contact Us Help Search canada.gc.ca Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets Home Issue Paper VICTIMS AND VULNERABLE GROUPS IN SOUTHERN SOMALIA May 1995 Disclaimer This document was prepared by the Research Directorate of the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. This document is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed or conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. For further information on current developments, please contact the Research Directorate. Table of Contents PREFACE ABOUT THE AUTHOR GLOSSARY 1. INTRODUCTION: SCOPE, SOURCES AND METHODOLOGY 2. PHASES OF THE SOMALI CONFLICT: TARGETS AND VICTIMS 3. CATEGORIES OF VULNERABLE GROUPS 3.1 Major Clans 3.2 Minority Clans 3.3 The Situation for Women and Children APPENDIX I: NOTES ON SELECTED MINORITY COMMUNITIES A. Bajuni B. Bravanese C. Somali "Bantu" 1 of 21 9/17/2013 9:22 AM Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/VICTIMS A... D. Rahanweyn (Reewin) E. Caste Groups APPENDIX II: MAPS Map I: Operation Restore Hope Map II: Population Density Map III: Distribution of Dialectal Groups REFERENCES PREFACE Due to the nature of and the difficulty in obtaining written documentation on the current situation in Somalia, Professor Lee Cassanelli of the University of Pennsylvania was commissioned to research and write this paper to address the information needs of those involved in the Canadian refugee determination process. -

Clanship, Conflict and Refugees: an Introduction to Somalis in the Horn of Africa

CLANSHIP, CONFLICT AND REFUGEES: AN INTRODUCTION TO SOMALIS IN THE HORN OF AFRICA Guido Ambroso TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I: THE CLAN SYSTEM p. 2 The People, Language and Religion p. 2 The Economic and Socials Systems p. 3 The Dir p. 5 The Darod p. 8 The Hawiye p. 10 Non-Pastoral Clans p. 11 PART II: A HISTORICAL SUMMARY FROM COLONIALISM TO DISINTEGRATION p. 14 The Colonial Scramble for the Horn of Africa and the Darwish Reaction (1880-1935) p. 14 The Boundaries Question p. 16 From the Italian East Africa Empire to Independence (1936-60) p. 18 Democracy and Dictatorship (1960-77) p. 20 The Ogaden War and the Decline of Siyad Barre’s Regime (1977-87) p. 22 Civil War and the Disintegration of Somalia (1988-91) p. 24 From Hope to Despair (1992-99) p. 27 Conflict and Progress in Somaliland (1991-99) p. 31 Eastern Ethiopia from Menelik’s Conquest to Ethnic Federalism (1887-1995) p. 35 The Impact of the Arta Conference and of September the 11th p. 37 PART III: REFUGEES AND RETURNEES IN EASTERN ETHIOPIA AND SOMALILAND p. 42 Refugee Influxes and Camps p. 41 Patterns of Repatriation (1991-99) p. 46 Patterns of Reintegration in the Waqoyi Galbeed and Awdal Regions of Somaliland p. 52 Bibliography p. 62 ANNEXES: CLAN GENEALOGICAL CHARTS Samaal (General/Overview) A. 1 Dir A. 2 Issa A. 2.1 Gadabursi A. 2.2 Isaq A. 2.3 Habar Awal / Isaq A.2.3.1 Garhajis / Isaq A. 2.3.2 Darod (General/ Simplified) A. 3 Ogaden and Marrahan Darod A. -

Inside Kenya's War on Terror: Breaking the Cycle of Violence in Garissa

Inside Kenya’s war on terror: breaking the cycle of violence in Garissa Christopher Wakube, Thomas Nyagah, James Mwangi and Larry Attree Inside Kenyas war on terror: The name of Garissa county in Kenya was heard all over the world after al-Shabaab shot breaking the cycle of violence dead 148 people – 142 of them students – at Garissa University College in April 2015. But the in Garissa story of the mounting violence leading up to that horrific attack, of how and why it happened, I. Attacks in Garissa: towards and of how local communities, leaders and the government came together in the aftermath the precipice to improve the security situation, is less well known. II. Marginalisation and division But when you ask around, it quickly becomes clear that Garissa is a place where divisions and in Garissa dangers persist – connected to its historic marginalisation, local and national political rivalries III. “This is about all of us” – in Kenya, and the ebb and flow of conflict in neighbouring Somalia. Since the attack, the local perceptions of violence security situation has improved in Garissa county, yet this may offer no more than a short IV. Rebuilding trust and unity window for action to solve the challenges and divisions that matter to local people – before other forces and agendas reassert their grip. V. CVE job done – or a peacebuilding moment to grasp? This article by Saferworld tells Garissa’s story as we heard it from people living there. Because Garissa stepped back from the brink of terror-induced polarisation and division, it is in some Read more Saferworld analysis ways a positive story with global policy implications. -

Human Rights and Security in Central and Southern Somalia

Danish 2/2004 Immigration Service ENG Human rights and security in central and southern Somalia Joint Danish, Finnish, Norwegian and British fact-finding mission to Nairobi, Kenya 7- 21 January 2004 Copenhagen, March 2004 The Danish Immigration Service Ryesgade 53 DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø Phone: + 45 35 36 66 00 Website: www.udlst.dk E-mail: [email protected] List of reports on fact finding missions in 2003 and 2004 Sikkerheds- og beskyttelsesforhold for minoritetsbefolkninger, kvinder og børn i Somalia Marts 2003: 1 Menneskerettighedsforhold i Burundi Maj 2003: 2 Dobbeltstraf mv. i Serbien Maj 2003:3 Joint British-Danish Fact Finding Mission to Damascus, Amman and Geneva on Conditions in Iraq August 2003: 4 Indrejse- og opholdsbetingelser for statsløse palæstinensere i Libanon November 2003: 5 Sikkerheds- og menneskeretsforhold for rohingyaer i Burma og Bangladesh December 2003: 6 Fact-finding mission til Amman vedrørende asylrelevante forhold i Irak Januar 2004: 1 Human rights and security in central and southern Somalia Marts 2004 : 2 Human rights and security in central and southern Somalia Introduction........................................................................................................................5 1 Political developments ...................................................................................................7 1.1 Peace negotiations in Kenya ......................................................................................................7 1.2 Agreement on new Transitional Charter..................................................................................10 -

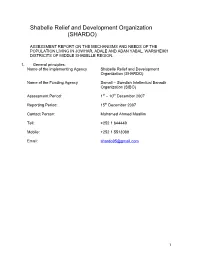

Shabelle Relief and Development Organization (SHARDO)

Shabelle Relief and Development Organization (SHARDO) ASSESSMENT REPORT ON THE MECHANISMS AND NEEDS OF THE POPULATION LIVING IN JOWHAR, ADALE AND ADAN YABAL, WARSHEIKH DISTRICITS OF MIDDLE SHABELLE REGION. 1. General principles: Name of the implementing Agency Shabelle Relief and Development Organization (SHARDO) Name of the Funding Agency Somali – Swedish Intellectual Banadir Organization (SIBO) Assessment Period: 1st – 10th December 2007 Reporting Period: 15th December 2007 Contact Person: Mohamed Ahmed Moallim Tell: +252 1 644449 Mobile: +252 1 5513089 Email: [email protected] 1 2. Contents 1. General Principles Page 1 2. Contents 2 3. Introduction 3 4. General Objective 3 5. Specific Objective 3 6. General and Social demographic, economical Mechanism in Middle Shabelle region 4 1.1 Farmers 5 1.2 Agro – Pastoralists 5 1.3 Adale District 7 1.4 Fishermen 2 3. Introduction: Middle Shabelle is located in the south central zone of Somalia The region borders: Galgadud to the north, Hiran to the West, Lower Shabelle and Banadir regions to the south and the Indian Ocean to the east. A pre – war census estimated the population at 1.4 million and today the regional council claims that the region’s population is 1.6 million. The major clans are predominant Hawie and shiidle. Among hawiye clans: Abgal, Galjecel, monirity include: Mobilen, Hawadle, Kabole and Hilibi. The regional consists of seven (7) districts: Jowhar – the regional capital, Bal’ad, Adale, A/yabal, War sheikh, Runirgon and Mahaday. The region supports livestock production, rain-fed and gravity irrigated agriculture and fisheries, with an annual rainfall between 150 and 500 millimeters covering an area of approximately 60,000 square kilometers, the region has a 400 km coastline on Indian Ocean. -

(I) the SOCIAL STRUCTUBE of Soumn SOMALI TRIB by Virginia I?

(i) THE SOCIAL STRUCTUBE OF SOumN SOMALI TRIB by Virginia I?lling A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of London. October 197]. (ii) SDMMARY The subject is the social structure of a southern Somali community of about six thousand people, the Geledi, in the pre-colonial period; and. the manner in which it has reacted to colonial and other modern influences. Part A deals with the pre-colonial situation. Section 1 deals with the historical background up to the nineteenth century, first giving the general geographic and ethnographic setting, to show what elements went to the making of this community, and then giving the Geledj's own account of their history and movement up to that time. Section 2 deals with the structure of the society during the nineteenth century. Successive chapters deal with the basic units and categories into which this community divided both itself and the others with which it was in contact; with their material culture; with economic life; with slavery, which is shown to have been at the foundation of the social order; with the political and legal structure; and with the conduct of war. The chapter on the examines the politico-religious office of the Sheikh or Sultan as the focal point of the community, and how under successive occupants of this position, the Geledi became the dominant power in this part of Somalia. Part B deals with colonial and post-colonial influences. After an outline of the history of Somalia since 1889, with special reference to Geledi, the changes in society brought about by those events are (iii) described. -

Somalia: Researched and Compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 5 July 2010

Somalia: Researched and compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 5 July 2010 Information required on the Somali clans/tribes Marehan and Marjeteen, particularly their relations with the Bajuni Noufail Are the Bajuni Noufail being discriminated against by the other two clans? Information on the Somali clans/tribes Marehan and Marjeteen and their relations with the Bajuni was scarce among the sources consulted by the Refugee Documentation Centre within time constraints. Dr Joakim Gundel is quoted in an Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation (ACCORD) COI Workshop as follows: “The Darood are commonly divided into three major groups referred to as Ogaden, Marehan, and Harti. The Harti are composed of the Majerteen who now are found in Puntland mainly, and the Dulbahante and Warsangeli who mainly live within the borders of Somaliland. Puntland almost entirely overlaps with the Majerteen clan family.14 The Marehan inhabit South-Central Somalia, where they are dominant in Gedo region.” (Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation (ACCORD) (15 May 2009) Clans in Somalia - Report on a Lecture by Joakim Gundel, COI Workshop Vienna, p. 12) A document from the Danish Refugee Council/Novib-Oxfam states: “Luuq, which is located in the Southern region of Gedo, shares much of the history of the Raxanweyn and the Geledi Sultanate as their Gasargude Sultanate was closely linked with the Geledi. Here too, you find that nomadic clans have settled and mixed with the sedentary people, however here the nomadic element was primarily represented by the Marehan from the Darood clan family. -

From the Bottom

Conflict Early Warning Early Response Unit From the bottom up: Southern Regions - Perspectives through conflict analysis and key political actors’ mapping of Gedo, Middle Juba, Lower Juba, and Lower Shabelle - SEPTEMBER 2013 With support from Conflict Dynamics International Conflict Early Warning Early Response Unit From the bottom up: Southern Regions - Perspectives through conflict analysis and key political actors’ mapping of Gedo, Middle Juba, Lower Juba, and Lower Shabelle Version 2 Re-Released Deceber 2013 with research finished June 2013 With support from Conflict Dynamics International Support to the project was made possible through generous contributions from the Government of Norway Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Government of Switzerland Federal Department of Foreign Affairs. The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the official position of Conflict Dynamics International or of the Governments of Norway or Switzerland. CONTENTS Abbreviations 7 ACKNOWLEDGMENT 8 Conflict Early Warning Early Response Unit (CEWERU) 8 Objectives 8 Conflict Dynamics International (CDI) 8 From the Country Coordinator 9 I. OVERVIEW 10 Social Conflict 10 Cultural Conflict 10 Political Conflict 10 II. INTRODUCTION 11 Key Findings 11 Opportunities 12 III. GEDO 14 Conflict Map: Gedo 14 Clan Chart: Gedo 15 Introduction: Gedo 16 Key Findings: Gedo 16 History of Conflict: Gedo 16 Cross-Border Clan Conflicts 18 Key Political Actors: Gedo 19 Political Actor Mapping: Gedo 20 Clan Analysis: Gedo 21 Capacity of Current Government Administration: Gedo 21 Conflict Mapping and Analysis: Gedo 23 Conflict Profile: Gedo 23 Conflict Timeline: Gedo 25 Peace Initiative: Gedo 26 IV. MIDDLE JUBA 27 Conflict Map: Middle Juba 27 Clan Chart: Middle Juba 28 Introduction: Middle Juba 29 Key Findings: Middle Juba 29 History of Conflict : Middle Juba 29 Key Political Actors: Middle Juba 29 Political Actor Mapping: Middle Juba 30 Capacity of Current Government Administration: Middle Juba 31 Conflict Mapping and Analysis: Middle Juba 31 Conflict Profile: Middle Juba 31 V.