Social Realism and Victorian Morality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laboratories of Creativity : the Alma-Tademas' Studio-Houses and Beyond

This is a repository copy of Laboratories of Creativity : The Alma-Tademas' Studio-Houses and Beyond. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/134913/ Version: Published Version Article: (2018) Laboratories of Creativity : The Alma-Tademas' Studio-Houses and Beyond. British Art Studies. 10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-09/conversation Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial (CC BY-NC) licence. This licence allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, and any new works must also acknowledge the authors and be non-commercial. You don’t have to license any derivative works on the same terms. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ British Art Studies Summer 2018 British Art Studies Issue 9, published 7 August 2018 Cover image: Jonathan Law, Pattern, excerpt from ilm, 2018.. Digital image courtesy of Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art with support from the staf of Leighton House Museum, The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. PDF generated on 7 August 2018 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading oline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identiiers) provided within the online article. -

DD391 Papers of Alexander Macdonald of Kepplestone and His Trustees

DD391 Papers of Alexander Macdonald of Kepplestone and his trustees c.1852 - 1903 The fonds consists of correspondence and other papers generated by Alexander Macdonald, including letters from the artists that Macdonald patronised. The trustees' papers include minutes, accounts, vouchers and correspondence detailing their administration of Macdonald's estate from 1884 until the division of the estate among the residuary legatees in 1902. The bundles listed by the National Register of Archives (Scotland) have not been altered since their deposit in the City Archives. During listing of the remaining papers, any other original bundles have been preserved intact. Bundles aggregated by the archivist during listing are indicated in the list with an asterisk. (15 boxes and one volume) DD391/1 Macdonald of Kepplestone: trust disposition, inventory, executry and subsidiary legal papers (1861, 1882-1885) 18611882 - 1885 DD391/1/1: Trust disposition and deed of settlement (1885); DD391/1/2: Copy trust disposition and settlement (1882) DD391/1/3: Draft abstract deed of settlement (1884); DD391/1/4: Inventories of estate (1885); DD391/1/5: Confirmation of executors (1885); DD391/1/6: Copy contract of marriage between Alexander Macdonald and Miss Hope Gordon (3 June 1861). (9 items) DD391/1/1 Alexander Macdonald of Kepplestone: Trust disposition and deed of settlement, 11 December 1882, 1885 1882 - 1885 *Trust disposition and deed of settlement of Alexander Macdonald dated 11 December 1882. Printed at the Aberdeen Journal Office, 1885 (1 bundle, 14 copies) DD391/1/2 Alexander Macdonald of Kepplestone: copy trust disposition and settlement, 11 December 1882 11 December 1882 *Copy trust disposition and settlement of Alexander Macdonald, and two draft trust dispositions and deed of settlements, 11 December 1882 (1 bundle, 3 items) DD391/1/3 Alexander Macdonald of Kepplestone: draft abstract deed of settlement, 11 December 1882 11 December 1882 *Draft abstract deed of settlement of Alexander Macdonald dated 11 December 1882. -

Late-Victorian Artists Presented As Strand Celebrities Type Article

Title "Peeps" or "Smatter and Chatter": Late-Victorian Artists Presented as Strand Celebrities Type Article URL https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/14210/ Dat e 2 0 1 9 Citation Dakers, Caroline (2019) "Peeps" or "Smatter and Chatter": Late-Victorian Artists Presented as Strand Celebrities. Victorian Periodicals Review. pp. 311-338. ISSN 0709-4698 Cr e a to rs Dakers, Caroline Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected] . License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author “Peeps,” or “Smatter and Chatter”: Late-Victorian Artists Presented as Strand Celebrities CAROLINE DAKERS I had not been at the hotel [in Switzerland] two hours before the parson put it [the Strand] into my hands. Certainly every person in the hotel had read it. It is true that some parts have a sickly flavour, perhaps only to us! I heard many remarks such as, “Oh! How interesting!” The rapture was general concerning your house. Such a house could scarcely have been imagined in London.1 Harry How’s “Illustrated Interview” with the Royal Academician Luke Fildes in his luxurious studio house in London’s Holland Park may have seemed a little “sickly” to Fildes and his brother-in-law Henry Woods, but such publicity was always welcome in an age when celebrity sold paintings. As Julie Codell demonstrates in The Victorian Artist: Artists’ Lifewritings in Britain ca. 1870–1910, late nineteenth-century art periodicals played an important role in building and maintaining the public’s interest in living artists. -

The Role of the Royal Academy in English Art 1918-1930. COWDELL, Theophilus P

The role of the Royal Academy in English art 1918-1930. COWDELL, Theophilus P. Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20673/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version COWDELL, Theophilus P. (1980). The role of the Royal Academy in English art 1918-1930. Doctoral, Sheffield Hallam University (United Kingdom).. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk onemeia u-ny roiyiecnmc 100185400 4 Mill CC rJ o x n n Author Class Title Sheffield Hallam University Learning and IT Services Adsetts Centre City Campus Sheffield S1 1WB NOT FOR LOAN Return to Learning Centre of issue Fines are charged at 50p per hour Sheffield Haller* University Learning snd »T Services Adsetts Centre City Csmous Sheffield SI 1WB ^ AUG 2008 S I2 J T 1 REFERENCE ProQuest Number: 10702010 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10702010 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

A Century of British Painting a Century of British Painting

A Century of British Painting A Century of British Painting Foreword There’s a passage in Tess of the D’Urbervilles, This year’s exhibition is no exception; where Hardy describes the complete sensory in between Greaves and Spear are works by experience of walking across a field, the thrum Farquharson, Tuke, La Thangue, Hemy, and of insects, motes and sunbeams, the ammoniac Heath, artists whose quiet social realism tang of cows, snail shells crunching underfoot. developed out of the sincere connection It’s a very sensual account, and given that it they held to their part of Britain. Masters at comes from what is still held to be one of the manipulating tone and perspective, these most sentimental novels of the Victorian era, artists never tried to modify the realties of their surprisingly unromantic. Farquharson’s Grey world, only the ‘light’ in which they are seen. Morning immediately struck me as a perfect Following on, are pictures by Bond, Knight, cover illustration for one of Hardy’s novels, Wyllie and other artists who explored realism, which led me to get out my copy of Tess. alongside the possibilities of Impressionism to While I skimmed some favourite passages, his depict rural subjects and the more communal characters began to take on faces painted by narratives of maritime trade: the backbone of La Thangue; as I later learned, when the book the British Empire. Well into the post-WWI was serialised in The Graphic, it was illustrated era, Impressionism would prove the perfect by Hubert von Herkomer. vehicle for depicting city life and genteel The pictures in this catalogue cover privilege; sport and leisure, the development of approximately 100 years. -

British Canvas, Stretcher and Panel Suppliers' Marks. Part 8, Charles

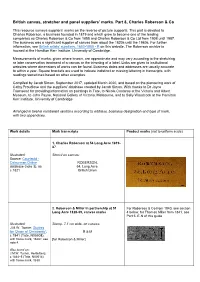

British canvas, stretcher and panel suppliers’ marks. Part 8, Charles Roberson & Co This resource surveys suppliers’ marks on the reverse of picture supports. This part is devoted to Charles Roberson, a business founded in 1819 and which grew to become one of the leading companies as Charles Roberson & Co from 1855 and Charles Roberson & Co Ltd from 1908 until 1987. The business was a significant supplier of canvas from about the 1820s until the 1980s. For further information, see British artists' suppliers, 1650-1950 - R on this website. The Roberson archive is housed at the Hamilton Kerr Institute, University of Cambridge. Measurements of marks, given where known, are approximate and may vary according to the stretching or later conservation treatment of a canvas or the trimming of a label. Links are given to institutional websites where dimensions of works can be found. Business dates and addresses are usually accurate to within a year. Square brackets are used to indicate indistinct or missing lettering in transcripts, with readings sometimes based on other examples. Compiled by Jacob Simon, September 2017, updated March 2020, and based on the pioneering work of Cathy Proudlove and the suppliers’ database created by Jacob Simon. With thanks to Dr Joyce Townsend for providing information on paintings in Tate, to Nicola Costaras at the Victoria and Albert Museum, to John Payne, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, and to Sally Woodcock at the Hamilton Kerr Institute, University of Cambridge. Arranged in twelve numbered sections according to address, business designation and type of mark, with two appendices. Work details Mark transcripts Product marks (not to uniform scale) 1. -

Hubert Von Herkomer, R.A.; a Study and a Biography

Hubert von Herkomer, R.A. A^ l:I</rtra^ c/^tLe^ "irfU't ani -/iLf r/u/dre^i //^/(^J '^^fom a/i,^/<Aa Hubert von Herkomer R.A. 4 A Study and a Biography By A. L. Baldry : INFLUENCE" AUTHOR OF "SIR J. E. MILLAIS, BART., P.R.A. HIS ART AND "albert MOORE: HIS LIFE AND WORKS," ETC. ^ London George Bell and Sons 1901 SEP 27 1967 '^"^ITY OF TOftO# ci-nswicK press: Charles whittingham and co. TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON. PREFACE would be impossible, even if it were desirable, to exclude personal ITdetails from a book which deals with the artistic accomplishment of Professor Hubert von Herkomer. The circumstances of his life and the character of his work are so inseparably connected that any attempt to trace his progress in the world of art involves also a history of himself and a study of his temperament. The man must be pictured in order to make intelligible the nature of his effort. Little incidents in his boyhood, and seemingly trivial events in his maturer years, have played a definite part in the shaping of his career, and have helped him to a clearer expression of his own personality. Heredity and associations have been factors of the utmost importance in the development of his intentions and the direction of his aims. Therefore in these pages there is at least as much said about the man as about the works he has produced. His views and opinions are set forth with sufficient elaboration to explain his attitude on artistic questions, and instances from his own experience are freely given to show the manner in which he has approached the problems of his profession. -

Luke Fildes's the Doctor, Narrative Painting, and The

Victorian Literature and Culture (2016), 44, 641–668. © Cambridge University Press 2016. 1060-1503/16 doi:10.1017/S1060150316000097 LUKE FILDES’S THE DOCTOR, NARRATIVE PAINTING, AND THE SELFLESS PROFESSIONAL IDEAL By Barry Milligan SINCE ITS INTRODUCTION at the Royal Academy exhibition of 1891, Luke Fildes’s painting The Doctor has earned that often hyperbolic adjective “iconic.” Immediately hailed as “the picture of the year” (“The Royal Academy,” “The Doctor,” “Fine Arts”), it soon toured the nation as part of a travelling exhibition, in which it “attracted most attention” (“Liverpool Autumn Exhibition”) and so affected spectators that one was even struck dead on the spot (“Sudden Death”). Over the following decades it spawned a school of imitations, supposed companion pictures, poems, parodies, tableaux vivants, an early Edison film, and a mass- produced engraving that graced middle-class homes and doctors’ offices in Britain and abroad for generations to come and was reputedly the highest-grossing issue ever for the prominent printmaking firm of Agnew & Sons (Dakers 265–66).1 When Fildes died in 1927 after a career spanning seven decades and marked by many commercial successes and even several royal portraits, his Times obituary nonetheless bore “The Doctor” as its sub-headline (“Sir Luke Fildes”) and sparked a lively discussion of the painting in the letters column for several issues thereafter (“Points From Letters” 2, 4, 5 Mar. 1927). Although the animus against things Victorian in the early twentieth century shadowed The Doctor it -

Annual Report 2017-2018 Contents 2

Annual Report 2017-2018 Contents 2 3 Director’s Report 13 Acquisitions 21 Works of art lent to public exhibitions 24 Long-term loans outside Government 30 Advisory Committee members 31 GAC staff Cover Image: Visitors to An Eyeful of Wry taking their free jokes by artist Peter Liversidge. © University of Hull / Photo: Anna Bean Director’s Report 3 Peter Liversidge’s commisioned work for An Eyeful of Wry at Hull University Library. © University of Hull / Photo: Anna Bean Once more, the Government Art Collection (GAC) An Eyeful of Wry illustrated a healthy note of parody. Gags, slapstick, has experienced an eventful year and achieved The major highlight of our public projects this year clowns and comics were referenced in Twenty Six an exciting range of projects. We were delighted was An Eyeful of Wry, a GAC-curated exhibition (Drawing and Falling Things), six videos by Wood to present An Eyeful of Wry, an exhibition of that opened in October at the Brynmor Jones and Harrison, whose deadpan gestures added to works from the Collection as part of UK City of Library Gallery, University of Hull, during the final the overall sense of farce. 4’ 33” (Prepared Pianola Culture 2017. We continued to select and install season of the UK City of Culture programme. for Roger Bannister), Mel Brimfield’s gaudy funfair new displays for government buildings in the UK pianola took visitors on a giddying musical ride and at several diplomatic posts around the world. The exhibition originated from an idea first around an Olympic athletics track. Across each site, art from the GAC revitalises explored as a special display for visitors to the the cultural context against which ministerial GAC’s premises in London. -

English Romantic Art Romantic Art

1850-1920 English Romantic Art Romantic Art shepherd gallery ENGLISH ROMANTIC ART 1850–1920 autumn 2005 English Romantic Art 1850-1920 English Romantic Art 1850-1920 September 20th – October 22nd, 2005 Shepherd & Derom Galleries in association with Campbell Wilson Christopher Wood cat. 1 Herbert Gustave Schmalz (1856–1935) A Fair Beauty Signed and dated 1889; oil on canvas, 24 × 20 ins Provenance: George Hughes, Newcastle; Mawson, Swan & Morgan, Newcastle; Private Collection. ‘Another Victorian worthy who enjoyed a great reputation in his day was Herbert Schmalz. He painted subjects from classical and biblical history, only choosing episodes which offered opportunities for elaborate and exotic architectural settings.’ (Christopher Wood, Olympian Dreamers p. 254.) In 1890 he visited Jerusalem and the Holy Land to collect material for his biblical subjects, many of which were turned into prints. He also painted portraits, and romantic figurative subjects. After the First World War, he changed his name to Carmichael. cat. 2 cat. 3 Henry John Stock (1853–1930) Arthur Gaskin (1862–1928) Portrait of The Hon.Mrs George Leveson-Gower Portrait of Joscelyne Verney Gaskin, aged 12 yrs, Signed and signed and inscribed on an old label on the reverse; oil on canvas, 28½ × 22½ ins the Artist’s Daughter Born in Soho, Stock went blind in childhood but recovered his sight on being sent to Inscribed and signed on the reverse; oil on canvas, 14 × 11 ins live in the New Forest. He studied at St Martin’s School of Art and the RA Schools and Provenance: Joscelyne Turner, née Gaskin, the artist’s daughter and thence by direct descent to present. -

A Stroll Through Tate Britain

A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN This two-hour talk is part of a series of twenty talks on the works of art displayed in Tate Britain, London, in June 2017. Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain. References and Copyright • The talk is given to a small group of people and all the proceeds, after the cost of the hall is deducted, are given to charity. • Our sponsored charities are Save the Children and Cancer UK. • Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain and the Tate’s online notes, display captions, articles and other information are used. • Each page has a section called ‘References’ that gives a link or links to sources of information. • Wikipedia, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Khan Academy and the Art Story are used as additional sources of information. • The information from Wikipedia is under an Attribution-Share Alike Creative Commons License. • Other books and articles are used and referenced. • If I have forgotten to reference your work then please let me know and I will add a reference or delete the information. 1 A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN • The History of the Tate • The Aesthetic Movement, 1860-1880 • Golden Age to Civil War, 1540-1650 • Late Victorians, 1880-1900 • Restoration to Georgians, 1650-1730 • The Edwardians, 1890-1910 • The Georgians, 1730-1780 • The Great War and After, 1910-1930 • Revolutionary Times, 1780-1810 • The Interwar Years, 1930s • Regency to Victorian, 1810-1840 • World War II and After, 1940-1960 • William Blake • Pop Art & Beyond, 1960-1980 • J. -

2015 · Maastricht TEFAF: the European Fine Art Fair 13–22 March 2015 LONDON MASTERPIECE LONDON 25 June–1 July 2015 London LONDON ART WEEK 3–10 July 2015

LOWELL LIBSON LTD 2 015 • New York · annual exhibition British Art: Recent Acquisitions at Stellan Holm · 1018 Madison Avenue 23–31 January 2015 · Maastricht TEFAF: The European Fine Art Fair 13–22 March 2015 LONDON MASTERPIECE LONDON 25 June–1 July 2015 London LONDON ART WEEK 3–10 July 2015 [ B ] LOWELL LIBSON LTD 2 015 • INDEX OF ARTISTS George Barret 46 Sir George Beaumont 86 William Blake 64 John Bratby 140 3 Clifford Street · Londonw1s 2lf John Constable 90 Telephone: +44 (0)20 7734 8686 John Singleton Copley 39 Fax: +44 (0)20 7734 9997 Email: [email protected] John Robert Cozens 28, 31 Website: www.lowell-libson.com John Cranch 74 John Flaxman 60 The gallery is open by appointment, Monday to Friday The entrance is in Old Burlington Street Edward Onslow Ford 138 Thomas Gainsborough 14 Lowell Libson [email protected] Daniel Gardner 24 Deborah Greenhalgh [email protected] Thomas Girtin 70 Jonny Yarker [email protected] Hugh Douglas Hamilton 44 Cressida St Aubyn [email protected] Sir Frank Holl 136 Thomas Jones 34 Sir Edwin Landseer 112 Published by Lowell Libson Limited 2015 Richard James Lane 108 Text and publication © Lowell Libson Limited Sir Thomas Lawrence 58, 80 All rights reserved ISBN 978 0 9929096 0 4 Daniel Maclise 106, 110 Designed and typeset in Dante by Dalrymple Samuel Palmer 96, 126 Photography by Rodney Todd-White & Son Ltd Arthur Pond 8 Colour reproduction by Altaimage Printed in Belgium by Albe De Coker Sir Joshua Reynolds 18 Cover: a sheet of 18th-century Italian George Richmond 114 paste paper (collection: Lowell Libson) George Romney 36 Frontispiece: detail from Thomas Rowlandson 52 William Turner of Oxford 1782–1862 The Sands at Barmouth, North Wales Simeon Solomon 130 see pages 116–119 Francis Towne 48 Overleaf: detail from William Turner of Oxford 116 John Robert Cozens 1752–1799, An Alpine Landscape, near Grindelwald, Switzerland J.M.W.