THE WILDERNESS Wilderness Is Universally Understood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ace Works Layout

South East Australian Transport Strategy Inc. SEATS A Strategic Transport Network for South East Australia SEATS’ holistic approach supports economic development FTRUANNSDPOINRTG – JTOHBSE – FLIUFETSUTYRLE E 2013 SEATS South East Australian Transport Strategy Inc. Figure 1. The SEATS region (shaded green) Courtesy Meyrick and Associates Written by Ralf Kastan of Kastan Consulting for South East Australian Transport Strategy Inc (SEATS), with assistance from SEATS members (see list of members p.52). Edited by Laurelle Pacey Design and Layout by Artplan Graphics Published May 2013 by SEATS, PO Box 2106, MALUA BAY NSW 2536. www.seats.org.au For more information, please contact SEATS Executive Officer Chris Vardon OAM Phone: (02) 4471 1398 Mobile: 0413 088 797 Email: [email protected] Copyright © 2013 SEATS - South East Australian Transport Strategy Inc. 2 A Strategic Transport Network for South East Australia Contents MAP of SEATS region ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary and proposed infrastructure ............................................................................ 4 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 6 2. Network objectives ............................................................................................................................... 7 3. SEATS STRATEGIC NETWORK ............................................................................................................ -

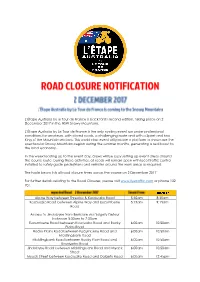

L'etape-ROAD CLOSURE NOTIFICATION

L’Étape Australia by le Tour de France is back for its second edition, taking place on 2 December 2017 in the NSW Snowy Mountains. L’Étape Australia by Le Tour de France is the only cycling event run under professional conditions for amateurs, with closed roads, a challenging route and with a Sprint and two King of the Mountain sections. This world class event will provide a platform to showcase the spectacular Snowy Mountains region during the summer months, generating a real boost to the local economy. In the week leading up to the event day, crews will be busy setting up event areas around the course route. During these activities, all roads will remain open with local traffic control installed to safely guide pedestrians and vehicles around the work areas as required. The table below lists all road closure times across the course on 2 December 2017. For further details relating to the Road Closures, please visit www.livetraffic.com or phone 132 701. Alpine Way between Thredbo & Kosciuszko Road 5:30am 8:30am Kosciuszko Road between Alpine Way and Eucumbene 5:15am 9:15am Road Access to Jindabyne from Berridale via Dalgety Detour between 5:00am to 7:00am Eucumbene Road between Kosciuszko Road and Rocky 6:00am 10:50am Plains Road Rocky Plains Road between Eucumbene Road and 6:00am 10:50am Middlingbank Road Middlingbank Road between Rocky Plain Road and 6:00am 10:50am Kosciuszko Road Jindabyne Road between Middlingbank Road and Myack 6:00am 10:50am Street Myack Street between Kosciuszko Road and Dalgety Road 6:00am 12:45pm Dalgety Road between Myack Street and The Snowy River 7:15am 12:15pm Way Campbell Street through Dalgety 7:15am 12:15pm The Snowy River Way between Dalgety and Barry Way 7:15am 2:00pm Barry Way between The Snowy River Way and Kosciuszko 7:30am 2:00pm Road Kosciuszko Road between Alpine Way and Perisher 8:30am 4:30pm NOTE: Emergency Services will be available to access properties impacted by the event closures at all times in case of an emergency. -

Alpine National Park – Around Benambra, Buchan and Bonang Visitor Guide

Alpine National Park – around Benambra, Buchan and Bonang Visitor Guide In the heart of the Australian Alps, this is one of Victoria’s largest and most remote areas of national park. The rugged landscape features the magnificent Snowy River and Suggan Buggan Valleys, the headwaters of the Murray River and spectacular peaks including the Cobberas and Mount Tingaringy. Getting there Tingaringy Falls – 800m, 50 minutes return. This part of the Alpine National Park adjoins Kosciuszko National Park along its northern boundary and the Snowy River National Park This short but steep walk leads through an open forest dominated to the south. by magestic Silvertop Ash and Red Stringybark before arriving at a The park is between 440 and 500 km north-east of Melbourne. The viewing platform, overlooking the beautiful waterfalls. The trail main access roads are all unsealed, narrow and winding and begins at Tingaringy Track, which is only accessible by 4WD and is generally unsuitable for caravans. closed seasonally. The Snowy River Road accesses the Snowy River at Willis on the Australian Alps Walking Track state border. This road becomes the Barry Way across the border and passes through Kosciuszko National Park en route to Jindabyne. The Bonang Road from Orbost is an alternative approach - McKillop The long distance Australian Alps Walking Track (AAWT) passes Road branches from it a few kilometres south of Bonang. through this area on its 650 km route between Walhalla (Gippsland, Vic.) and the Namadgi National Park Visitor Centre (near Canberra, The Limestone-Black Mountain Road crosses the central part of the ACT). -

Government Gazette of the STATE of NEW SOUTH WALES Number 108 Friday, 27 August 2010 Published Under Authority by Government Advertising

3995 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 108 Friday, 27 August 2010 Published under authority by Government Advertising LEGISLATION Online notification of the making of statutory instruments Week beginning 16 August 2010 THE following instruments were officially notified on the NSW legislation website (www.legislation.nsw.gov.au) on the dates indicated: Proclamations commencing Acts Food Amendment (Beef Labelling) Act 2009 No 120 (2010-462) — published LW 20 August 2010 Regulations and other statutory instruments Children and Young Persons (Care and Protection) (Child Employment) Regulation 2010 (2010-441) — published LW 20 August 2010 Crimes (Interstate Transfer of Community Based Sentences) Regulation 2010 (2010-443) — published LW 20 August 2010 Crimes Regulation 2010 (2010-442) — published LW 20 August 2010 Exhibited Animals Protection Regulation 2010 (2010-444) — published LW 20 August 2010 Food Amendment (Beef Labelling) Regulation 2010 (2010-463) — published LW 20 August 2010 Library Regulation 2010 (2010-445) — published LW 20 August 2010 Property (Relationships) Regulation 2010 (2010-446) — published LW 20 August 2010 Public Sector Employment and Management (General Counsel of DPC) Order 2010 (2010-447) — published LW 20 August 2010 Public Sector Employment and Management (Goods and Services) Regulation 2010 (2010-448) — published LW 20 August 2010 Road Transport (Vehicle Registration) Amendment (Number-Plates) Regulation 2010 (2010-449) — published LW 20 August 2010 State Records Regulation 2010 (2010-450) -

Impact of Wildfire on the Spotted-Tailed Quoll Dasyurus Maculatus in Kosciuszko National Park

Impact of wildfire on the spotted-tailed quoll Dasyurus maculatus in Kosciuszko National Park. James Patrick Dawson BSc A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science School of Physical, Environmental and Mathematical Sciences University College University of New South Wales A spotted-tailed quoll captured in the Jacobs River study area in 2004. Photo: J. Dawson. Certificate of Originality I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project’s design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged. James Patrick Dawson April 2005 Acknowledgements Firstly, I am sincerely grateful for the advice, assistance and support provided by my supervisors, Dr. Andrew Claridge and Dr. David Paull. From the start through to the conclusion of the project Andrew provided ideas, encouragement, enthusiasm and (most importantly) focus. In addition to the many instructive discussions, I am also thankful for Andrew’s company and unique humour that made tramping around the not-insignificant hills of Byadbo and playing with quolls so much fun. -

Kosciuszko National Park Closed Areas Date: 16 February 2020 at 10:55 To: [email protected]

From: Brindabella Ski Club [email protected] Subject: Kosciuszko National Park Closed Areas Date: 16 February 2020 at 10:55 To: [email protected] Sections of Kosciuszko National Park have been reopened, but areas which have been burnt or have ongoing fire suppression operations remain closed. Areas Recently Opened: • All areas south of Mt Jagungal and east of the following roads / trails are open to the public: Khancoban – Cabramurra Rd, Alpine Way and Cascade Trail (refer to map). This includes all backcountry areas which have not been impacted by fire. Overnight camping is permitted in these areas. This includes: o Kosciuszko Road - Jindabyne to Charlotte Pass o Guthega Road - Kosciuszko Road to Guthega Village o Charlotte Pass, Perisher Valley, Smiggin Holes, Guthega, Diggers Creek, Wilsons Valley, Sawpit Creek, Waste Point – visitors need to check whether resort facilities and hospitality venues are open for business o Alpine Way between Jindabyne and Thredbo Village o Thredbo Village and Thredbo resort lease area o Ngarigo, Thredbo Diggings and Island Bend campgrounds - for day use and overnight camping o Snowy Mountains Highway – visitors must stay within the road corridor and be aware of hazards such as damaged buildings and burnt trees o Blowering campgrounds - Log Bridge, The Pines, Humes Crossing and Yachting Point o All walks on the Main Range, including to Mt Kosciuszko and surrounding the alpine resort areas o Barry Way – open to the Victorian border. Lower Snowy picnic and campgrounds are open and include; Jacobs River, Halfway Flat, No Name, Pinch River, Jacks Lookout and Running Waters o Schlink Pass trail and associated huts (Horse Camp Hut, White River Hut, Schlink Hut, Valentine Hut) o Mt Jagungal. -

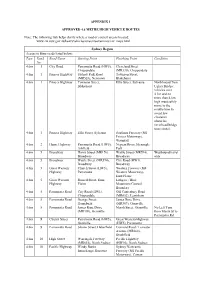

APPENDIX 1 APPROVED 4.6 METRE HIGH VEHICLE ROUTES Note: The

APPENDIX 1 APPROVED 4.6 METRE HIGH VEHICLE ROUTES Note: The following link helps clarify where a road or council area is located: www.rta.nsw.gov.au/heavyvehicles/oversizeovermass/rav_maps.html Sydney Region Access to State roads listed below: Type Road Road Name Starting Point Finishing Point Condition No 4.6m 1 City Road Parramatta Road (HW5), Cleveland Street Chippendale (MR330), Chippendale 4.6m 1 Princes Highway Sydney Park Road Townson Street, (MR528), Newtown Blakehurst 4.6m 1 Princes Highway Townson Street, Ellis Street, Sylvania Northbound Tom Blakehurst Ugly's Bridge: vehicles over 4.3m and no more than 4.6m high must safely move to the middle lane to avoid low clearance obstacles (overhead bridge truss struts). 4.6m 1 Princes Highway Ellis Street, Sylvania Southern Freeway (M1 Princes Motorway), Waterfall 4.6m 2 Hume Highway Parramatta Road (HW5), Nepean River, Menangle Ashfield Park 4.6m 5 Broadway Harris Street (MR170), Wattle Street (MR594), Westbound travel Broadway Broadway only 4.6m 5 Broadway Wattle Street (MR594), City Road (HW1), Broadway Broadway 4.6m 5 Great Western Church Street (HW5), Western Freeway (M4 Highway Parramatta Western Motorway), Emu Plains 4.6m 5 Great Western Russell Street, Emu Lithgow / Blue Highway Plains Mountains Council Boundary 4.6m 5 Parramatta Road City Road (HW1), Old Canterbury Road Chippendale (MR652), Lewisham 4.6m 5 Parramatta Road George Street, James Ruse Drive Homebush (MR309), Granville 4.6m 5 Parramatta Road James Ruse Drive Marsh Street, Granville No Left Turn (MR309), Granville -

City Water Technology Capability Statement Here

City Water Technology Capability Information July 2015 City Water Technology Pty Ltd ABN UN LQN PPT LUP NR / UNP Pacific Highway, Gordon, NSW NLSN, Australia T: +RM N UPUT MPPP F: +RM N UPUT MRRR W: www.citywater.com.au E: [email protected] City Water Technology Capability Information | 2 Table of Contents 1 About City Water Technology 3 1.1 Background 3 1.2 Our Consulting Approach 4 1.3 Our Organisation 4 1.4 Services Provided 4 2 Business Management System 5 2.1 Quality Management 5 2.2 Work Health & Safety 6 2.3 Environmental Management 7 3 Insurances 7 4 Previous Experience 8 4.1 Management Systems 8 4.2 Risk Management and Management Plans 8 4.3 Documents and Manuals 11 4.4 Water Treatment Investigation and Design 14 4.5 Wastewater Treatment Investigations 19 4.6 Water Treatment System Commissioning and Operation 20 4.7 Plant Audits 21 4.8 Bench and Pilot Plant Studies 22 4.9 Ground Water Management and Treatment 23 4.10 PuBlic and private swimming pool systems 24 4.11 Desalination 25 4.12 Pipeline Water Quality Issues 26 4.13 Ozone/ BAC 27 4.14 Taste and Odour and Algal Toxin Investigations 28 4.15 Water Reclamation Plants 29 4.16 Water Reuse 29 4.17 Solids Contact Clarifiers 29 4.18 Filtration 30 4.19 MemBranes for Water Treatment 31 4.20 Destratification of Reservoirs 32 4.21 Iron and Manganese Removal 32 4.22 Corrosion Issues 33 4.23 Sludge Handling 34 4.24 Computer-Based Tools 35 5 Key Personnel 35 5.1 Bruce Murray, Managing Director 35 5.2 Kirsten Hulse, Senior Process Engineer 36 5.3 Leonie Huxedurp, Principal Environmental -

Closed Areas: Kosciuszko National Park- Part Closure

Closed areas: Kosciuszko National Park - part closure Sections of Kosciuszko National Park have been reopened, but areas which have been burnt or have ongoing fire suppression operations remain closed. Areas Recently Opened: • All areas south of Mt Jagungal and east of the following roads / trails are open to the public: Khancoban – Cabramurra Rd, Alpine Way and Cascade Trail (refer to map). This includes all backcountry areas which have not been impacted by fire. Overnight camping is permitted in these areas. This includes: o Kosciuszko Road - Jindabyne to Charlotte Pass o Guthega Road - Kosciuszko Road to Guthega Village o Charlotte Pass, Perisher Valley, Smiggin Holes, Guthega, Diggers Creek, Wilsons Valley, Sawpit Creek, Waste Point – visitors need to check whether resort facilities and hospitality venues are open for business o Alpine Way between Jindabyne and Thredbo Village o Thredbo Village and Thredbo resort lease area o Ngarigo, Thredbo Diggings and Island Bend campgrounds - for day use and overnight camping o Snowy Mountains Highway – visitors must stay within the road corridor and be aware of hazards such as damaged buildings and burnt trees o Blowering campgrounds - Log Bridge, The Pines, Humes Crossing and Yachting Point o All walks on the Main Range, including to Mt Kosciuszko and surrounding the alpine resort areas o Barry Way – open to the Victorian border. Lower Snowy picnic and campgrounds are open and include; Jacobs River, Halfway Flat, No Name, Pinch River, Jacks Lookout and Running Waters o Schlink Pass trail and associated huts (Horse Camp Hut, White River Hut, Schlink Hut, Valentine Hut) o Mt Jagungal. Access to this area must be from Guthega Power Station or Guthega. -

Monaro REF Appendix 3 Biodiversity Assessment

Appendix 3 Biodiversity Assessment Kosciuszko Road (MR286) Barry Way to Alpine Way Lane Addition Biodiversity Assessment July 2017 BLANK PAGE Roads and Maritime Services Kosciuszko Road (MR286) Barry Way to Alpine Way Lane Addition Biodiversity Assessment July 2017 Prepared by Envirokey Pty Ltd Project Title: Biodiversity Assessment: MR286 Barry Way to Alpine Way Lane Addition Project Identifier : 17.EcIA-013 Project Location: \\ENVIROKEY\Public\Projects\RMS\Barry Way REF Revision Date Prepared by (name) Reviewed by (name) Approved by (name) Draft 14.03.2017 JW LS Steve Sass (CEnvP) Final Draft 17.05.2017 SS - Steve Sass (CEnvP) Final 02.07.2017 SS - Steve Sass (CEnvP) Executive summary EnviroKey were engaged by Roads and Maritime to carry out a Biodiversity Assessment (BA) for a proposal to add a lane to Kosciuszko Road (MR286) between Barry Way and Alpine Way. The proposal is located within the Snowy Monaro Regional Council local government area (formerly the Snowy River LGA). The study area is characterised by the occurrence of one native vegetation community: • Snow Gum - Candle Bark woodland on broad valley flats of the tablelands and slopes, South Eastern Highlands Bioregion (PCT 1191) - Including derived native grassland In addition, planted native and non-native vegetation was recorded in the study area. The native woodland vegetation is consistent with the description for Tablelands Snow Gum Grassy Woodland, an endangered ecological community listed on the NSW Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 (TSC Act). This listing also includes vegetation types derived from the removal of the canopy trees, therefore the derived grassland recorded within the study area also qualifies as the TEC. -

The First National Park : a Natural for World Heritage / Geoff Mosley

About The Author Geographer and enVironMental historian Dr Geoff Mosley is Australia’s most experienced world heritage assessor having been involved with the field since 1974 only two years after the signing of the World Heritage Convention. From that year, as CEO of the Australian Conservation Foundation, he led many successful World Heritage campaigns, including those for the Great Barrier Reef (inscribed 1981), Kakadu (1981, 1987 and 1992), The Tasmanian Wilderness (1982 and 1989), Central Eastern Rainforest Reserves (1986 and 1994), Uluru Kata Tjuta (1987 and 1994), Wet Tropics of Queensland (1988), and Fraser Island (1992). Since 1986 he has been an environmental consultant specialising in world heritage, has worked in that capacity for sev- eral Governments and NGOs, and is the author of many books on national parks and world heritage, including Australia’s Wilderness World Heritage Vol 1 World Heritage Areas (Weldon, 1988) co-authored with Penny Figgis. He has played a major role in the campaigns for the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area (inscribed 2000), and for the World Heritage listing of The Australian Alps and South East Forests, and Antarctica. In the early 1950s he joined the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) and has been a member of the IUCN’s World Commission on Protected Areas since 1979, reviewing world heritage nominations in Australia and overseas. From 1981 to 1988 he represented Australasia and Oceania on the governing body of IUCN. THE FIRST NATIONAL PARK A Natural For World Heritage by Dr Geoff Mosley Published by Envirobook, on behalf of Sutherland Shire Environment Centre Inc, Box 589 PO Sutherland 1499 www.ssec.org.au © Geoff Mosley, 2012 National Library of Australia Cataloguing in publication Data: Author: Mosley, J. -

Schedule of Classified Roads and State and Regional Roads

Schedule of Classified Roads and Unclassified Regional Roads Changes to this document are captured in ‘Recently Gazetted Changes’: http://www.rms.nsw.gov.au/business-industry/partners-suppliers/lgr/arrangements-councils/road-classification.html Summary Roads and Maritime Services (RMS) is required under the Roads Act 1993 s163 (4) to keep a record of all classified roads. To satisfy this commitment, this document contains a record of the roads classified under sections 46, 47, 50 or 51 of the Roads Act 1993 that have a Legal Class of Highway, Main Road, Secondary Road or Tourist Road - as legally described by Declaration Order in the Government Gazette. To manage the extensive network of roads for which council is responsible under the Roads Act 1993, RMS in partnership with local government established an administrative framework of State, Regional, and Local Road categories. State Roads are managed and financed by RMS and Regional and Local Roads are managed and financed by councils. Regional Roads perform an intermediate function between the main arterial network of State Roads and council controlled Local Roads. Due to their network significance RMS provides financial assistance to councils for the management of their Regional Roads. The Regional Road category comprises two sub- categories: those Regional Roads that are classified pursuant to the Roads Act 1993, and those Regional Roads that are unclassified. For completeness, the Schedule includes unclassified Regional Roads. Local Roads are unclassified roads and therefore are not included in the Schedule. The recently introduced alpha-numeric route numbering (MAB) system used for wayfinding purposes in NSW does not directly relate to the legal classification of roads and has not been incorporated into this Schedule.