SWIFT AIR, LLC, Reorganized Debtor. ) ) ) ) ) Chapter 11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Columbus Regional Airport Authority

COLUMBUS REGIONAL AIRPORT AUTHORITY - PORT COLUMBUS INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT TRAFFIC REPORT October, 2009 11/24/2009 Airline Enplaned Passengers Deplaned Passengers Enplaned Air Mail Deplaned Air Mail Enplaned Air Freight Deplaned Air Freight Landings Landed Weight Air Canada Jazz - Regional 1,385 1,432 0 0 0 0 75 2,548,600 Air Canada Jazz Totals 1,385 1,432 0 0 0 0 75 2,548,600 AirTran 16,896 16,563 0 0 0 0 186 20,832,000 AirTran Totals 16,896 16,563 0 0 0 0 186 20,832,000 American 13,482 13,047 10,256 13,744 0 75 120 14,950,000 American Connection - Chautauqua 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 American Eagle 22,258 22,818 0 0 2,497 3,373 550 24,434,872 American Totals 35,740 35,865 10,256 13,744 2,497 3,448 670 39,384,872 Continental 5,584 5,527 24,724 17,058 6,085 12,750 57 6,292,000 Continental Express - Chautauqua 4,469 4,675 0 0 477 0 110 4,679,500 Continental Express - Colgan 2,684 3,157 0 0 0 0 69 4,278,000 Continental Express - CommutAir 1,689 1,630 0 0 0 0 64 2,208,000 Continental Express - ExpressJet 3,821 3,334 0 0 459 1,550 100 4,122,600 Continental Totals 18,247 18,323 24,724 17,058 7,021 14,300 400 21,580,100 Delta 14,640 13,970 0 0 9,692 38,742 119 17,896,000 Delta Connection - Atlantic SE 2,088 2,557 0 1 369 2 37 2,685,800 Delta Connection - Chautauqua 13,857 13,820 0 0 0 0 359 15,275,091 Delta Connection - Comair 1,890 1,802 0 0 0 0 52 2,444,000 Delta Connection - Mesa/Freedom 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Delta Connection - Pinnacle 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Delta Connection - Shuttle America 4,267 4,013 0 0 0 0 73 5,471,861 Delta Connection - SkyWest 0 0 0 0 -

(EU) 2018/336 of 8 March 2018 Amending Regulation

13.3.2018 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 70/1 II (Non-legislative acts) REGULATIONS COMMISSION REGULATION (EU) 2018/336 of 8 March 2018 amending Regulation (EC) No 748/2009 on the list of aircraft operators which performed an aviation activity listed in Annex I to Directive 2003/87/EC on or after 1 January 2006 specifying the administering Member State for each aircraft operator (Text with EEA relevance) THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to Directive 2003/87/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 October 2003 establishing a scheme for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the Community and amending Council Directive 96/61/ EC (1), and in particular Article 18a(3)(b) thereof, Whereas: (1) Directive 2008/101/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council (2) amended Directive 2003/87/EC to include aviation activities in the scheme for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the Union. (2) Commission Regulation (EC) No 748/2009 (3) establishes a list of aircraft operators which performed an aviation activity listed in Annex I to Directive 2003/87/EC on or after 1 January 2006. (3) That list aims to reduce the administrative burden on aircraft operators by providing information on which Member State will be regulating a particular aircraft operator. (4) The inclusion of an aircraft operator in the Union’s emissions trading scheme is dependent upon the performance of an aviation activity listed in Annex I to Directive 2003/87/EC and is not dependent on the inclusion in the list of aircraft operators established by the Commission on the basis of Article 18a(3) of that Directive. -

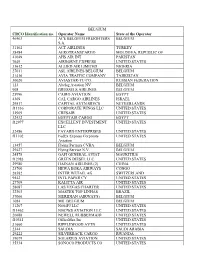

Prior Compliance List of Aircraft Operators Specifying the Administering Member State for Each Aircraft Operator – June 2014

Prior compliance list of aircraft operators specifying the administering Member State for each aircraft operator – June 2014 Inclusion in the prior compliance list allows aircraft operators to know which Member State will most likely be attributed to them as their administering Member State so they can get in contact with the competent authority of that Member State to discuss the requirements and the next steps. Due to a number of reasons, and especially because a number of aircraft operators use services of management companies, some of those operators have not been identified in the latest update of the EEA- wide list of aircraft operators adopted on 5 February 2014. The present version of the prior compliance list includes those aircraft operators, which have submitted their fleet lists between December 2013 and January 2014. BELGIUM CRCO Identification no. Operator Name State of the Operator 31102 ACT AIRLINES TURKEY 7649 AIRBORNE EXPRESS UNITED STATES 33612 ALLIED AIR LIMITED NIGERIA 29424 ASTRAL AVIATION LTD KENYA 31416 AVIA TRAFFIC COMPANY TAJIKISTAN 30020 AVIASTAR-TU CO. RUSSIAN FEDERATION 40259 BRAVO CARGO UNITED ARAB EMIRATES 908 BRUSSELS AIRLINES BELGIUM 25996 CAIRO AVIATION EGYPT 4369 CAL CARGO AIRLINES ISRAEL 29517 CAPITAL AVTN SRVCS NETHERLANDS 39758 CHALLENGER AERO PHILIPPINES f11336 CORPORATE WINGS LLC UNITED STATES 32909 CRESAIR INC UNITED STATES 32432 EGYPTAIR CARGO EGYPT f12977 EXCELLENT INVESTMENT UNITED STATES LLC 32486 FAYARD ENTERPRISES UNITED STATES f11102 FedEx Express Corporate UNITED STATES Aviation 13457 Flying -

U.S. Department of Transportation DOT Litigation News

DOT LITIGATION NEWS 1200 New Jersey Avenue, S.E. Office of the General Counsel Washington, D.C. 20590 Paul M. Geier Assistant General Counsel Telephone: (202) 366-4731 Fax: (202) 493-0154 for Litigation Peter J. Plocki Deputy Assistant General Counsel for Litigation October 31, 2011 Volume No. 11 Issue No. 2 Highlights Supreme Court grants review of Air carriers challenge most recent decision allowing non-pecuniary DOT airline passenger consumer damages for Privacy Act violations, protection rule, page 10 page 2 Aircraft owner groups challenge FAA Supreme Court grants review in case rule prohibiting blocking of flight data involving the preemptive scope of the without security basis, page 18 Locomotive Inspection Act, page 3 FMCSA sued over Mexican long-haul Court finds preemption in state law trucking pilot program, page 40 challenge to accessibility of airline ticket kiosks, plaintiffs appeal, page 8 D.C. Circuit upholds constitutionality of the “Murray Amendment,” page 43 Table of Contents Supreme Court Litigation 2 Departmental Litigation in Other Federal Courts 5 Recent Litigation News from DOT Modal Administrations Federal Aviation Administration 11 Federal Highway Administration 21 Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration 39 Federal Railroad Administration 41 Federal Transit Administration 43 Maritime Administration 46 Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration 47 Saint Lawrence Seaway Development Corporation 48 Index of Cases Reported in this Issue 50 DOT Litigation News October 31, 2011 Page 2 Supreme Court Litigation Supreme Court Grants Review of Mr. Cooper appealed, and the Ninth Circuit reversed. Cooper v. FAA, 622 F.3d 1016 Ninth Circuit Decision Allowing th Non-pecuniary Damages for (9 Cir. -

Terminal-Airline EPAX

Terminal-Airline EPAX Summary Data as of: 9/30/2016 12:00:00 AM Acronyms: MTD - Month to Date PFY - Previous Fiscal Year YTD - Year Run: 10/19/2016 12:00:15 AM to Date CFYTD - Current Fiscal Year FYTD PY: Sep 15 vs. FYTD: Sep 16 to Date MTD PFY: Sep 15 vs. MTD: Sep 16 EPAX MTD EPAX Var EPAX % Chg EPAX Var EPAX % Chg Terminal Airline Name PFY EPAX MTD MTD MTD EPAX PFYTD EPAX CFYTD FYTD FYTD American Airlines, Inc. 594,032 726,761 132,729 22.3% 6,960,972 8,215,159 1,254,187 18.0% Terminal A Total 594,032 726,761 132,729 22.3% 6,960,972 8,215,159 1,254,187 18.0% Envoy Air, Inc. 160,585 173,582 12,997 8.1% 2,616,848 1,999,418 (617,430) (23.6%) ExpressJet Airlines - American 98,699 49,480 (49,219) (49.9%) 867,684 828,327 (39,357) (4.5%) Terminal B Mesa Airlines - American 181,708 163,382 (18,326) (10.1%) 1,200,747 2,148,210 947,463 78.9% Total 440,992 386,444 (54,548) (12.4%) 4,685,279 4,975,955 290,676 6.2% American Airlines, Inc. 753,007 767,907 14,900 2.0% 9,750,980 9,175,257 (575,723) (5.9%) Terminal C Total 753,007 767,907 14,900 2.0% 9,750,980 9,175,257 (575,723) (5.9%) ABC Aerolineas, S.A. de C.V. 0 2,797 2,797 - 0 24,554 24,554 - Aeroenlaces Nacionales S.A. -

Columbus Regional Airport Authority

COLUMBUS REGIONAL AIRPORT AUTHORITY - PORT COLUMBUS INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT TRAFFIC REPORT September, 2009 10/27/2009 Airline Enplaned Passengers Deplaned Passengers Enplaned Air Mail Deplaned Air Mail Enplaned Air Freight Deplaned Air Freight Landings Landed Weight Air Canada Jazz - Regional 1,161 1,268 0 0 0 0 70 2,373,000 Air Canada Jazz Totals 1,161 1,268 0 0 0 0 70 2,373,000 AirTran 14,410 14,307 0 0 0 0 167 18,184,000 AirTran Totals 14,410 14,307 0 0 0 0 167 18,184,000 American 12,013 11,805 8,761 4,791 0 5,900 115 14,300,000 American Connection - Chautauqua 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 American Eagle 20,642 21,194 0 0 2,402 2,959 537 23,945,641 American Totals 32,655 32,999 8,761 4,791 2,402 8,859 652 38,245,641 Continental 8,094 7,845 40,110 18,472 6,016 36,555 81 9,422,000 Continental Express - Chautauqua 3,989 4,287 0 0 359 0 94 3,995,000 Continental Express - Colgan 3,256 2,921 0 0 0 0 74 4,588,000 Continental Express - CommutAir 543 515 0 0 0 0 23 793,500 Continental Express - ExpressJet 3,569 3,968 0 15 320 3,426 113 4,658,538 Continental Totals 19,451 19,536 40,110 18,487 6,695 39,981 385 23,457,038 Delta 13,312 13,570 0 0 7,785 29,589 116 17,076,000 Delta Connection - Atlantic SE 1,846 2,008 0 6 135 0 28 2,066,600 Delta Connection - Chautauqua 10,960 10,506 0 0 0 0 274 11,658,426 Delta Connection - Comair 2,325 2,045 0 0 0 0 59 2,773,000 Delta Connection - Mesa/Freedom 0 24 0 0 0 0 1 42,500 Delta Connection - Pinnacle 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Delta Connection - Shuttle America 7,035 7,070 0 0 0 0 144 10,791,161 Delta Connection - SkyWest 0 0 0 -

Publications Office

23.4.2021 ES Diar io Ofi cial de la Unión Europea L 139/1 II (Actos no legislativos) REGLAMENTOS REGLAMENTO (UE) 2021/662 DE LA COMISIÓN de 22 de abril de 2021 por el que se modifica el Reglamento (CE) n.o 748/2009 de la Comisión sobre la lista de operadores de aeronaves que han realizado una actividad de aviación enumerada en el anexo I de la Directiva 2003/87/CE el 1 de enero de 2006 o a partir de esta fecha, en la que se especifica el Estado miembro responsable de la gestión de cada operador (Texto pertinente a efectos del EEE) LA COMISIÓN EUROPEA, Visto el Tratado de Funcionamiento de la Unión Europea, Vista la Directiva 2003/87/CE del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo, de 13 de octubre de 2003, por la que se establece un régimen para el comercio de derechos de emisión de gases de efecto invernadero en la Unión y por la que se modifica la Directiva 96/61/CE del Consejo (1), y en particular su artículo 18 bis, apartado 3, letra b), Considerando que: (1) Las actividades de la aviación están incluidas en el régimen para el comercio de derechos de emisión de gases de efecto invernadero dentro de la Unión (en lo sucesivo, «RCDE UE»). (2) El Reglamento (CE) n.o 748/2009 de la Comisión (2) establece una lista de los operadores de aeronaves que han realizado una actividad de aviación enumerada en el anexo I de la Directiva 2003/87/CE el 1 de enero de 2006 o a partir de esta fecha. -

Columbus Regional Airport Authority

COLUMBUS REGIONAL AIRPORT AUTHORITY - PORT COLUMBUS INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT TRAFFIC REPORT June, 2009 7/28/2009 Airline Enplaned Passengers Deplaned Passengers Enplaned Air Mail Deplaned Air Mail Enplaned Air Freight Deplaned Air Freight Landings Landed Weight Air Canada Jazz - Regional 1,277 1,333 0 0 0 0 74 2,508,600 Air Canada Jazz Totals 1,277 1,333 0 0 0 0 74 2,508,600 AirTran 17,519 16,486 0 0 0 0 180 18,720,000 AirTran Totals 17,519 16,486 0 0 0 0 180 18,720,000 American 12,890 12,644 7,772 9,657 0 68 103 12,928,500 American Connection - Chautauqua 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 American Eagle 22,409 21,285 0 0 4,602 4,038 533 24,114,479 American Totals 35,299 33,929 7,772 9,657 4,602 4,106 636 37,042,979 Continental 6,253 6,131 21,678 12,989 6,207 18,009 57 6,496,000 Continental Express - Chautauqua 4,047 4,265 0 0 365 100 86 3,659,500 Continental Express - Colgan 2,640 3,422 0 0 0 0 60 3,720,000 Continental Express - CommutAir 2,239 1,973 0 0 0 0 72 2,484,000 Continental Express - ExpressJet 5,540 4,931 0 94 410 4,598 129 5,318,154 Continental Totals 20,719 20,722 21,678 13,083 6,982 22,707 404 21,677,654 Delta 17,055 15,501 0 0 7,167 30,267 127 18,930,000 Delta Connection - Atlantic SE 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Delta Connection - Chautauqua 15,301 15,005 0 0 0 0 400 17,019,600 Delta Connection - Comair 846 888 0 0 0 0 27 1,269,000 Delta Connection - Mesa/Freedom 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Delta Connection - Pinnacle 137 145 0 0 0 0 2 150,000 Delta Connection - Shuttle America 7,468 7,338 0 0 0 0 127 9,482,481 Delta Connection - SkyWest 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 47,000 Delta -

Chi-Stat 2012 Attendees

Chi-Stat 2012 Attendees Thomas Considine 3 Points Aviation Hamish Davidson 3-D Aviation LLC Steve Williams A J Walter Aviation David Fish AAR Corp Emily Campbell AAR Aircraft Sales & Leasing Phillip Raymond AAR Aircraft Sales & Leasing Chris Wilko AAR Aircraft Turbine Center David Tatum AAR Aircraft Turbine Center Johnny Williams AAR Allen Asset Management Amy Becker AAR Corp. Andrew Schmit AAR Corp. Chris Jessup AAR Corp. Christine Bognar AAR Corp. Dany Kleiman AAR Corp. Darren Spiegel AAR Corp. David May AAR Corp. David Prusiecki AAR Corp. Eric Miller AAR Corp. Gary Hundley AAR Corp. Harold Kugelman AAR Corp. Jennifer Griffin AAR Corp. Joseph Giarritano AAR Corp. Kevin Rogers AAR Corp. Michael Storch AAR Corp. Vincent Misciagna AAR Systems & Structures U.S. John Graves ACG International LTD Quentin Brasie ACI Aviation Consulting Richard Young ACI Aviation Consulting Jan D'Angelo AdamWorks Nora Muller Advantage Technological Resourcing Bart Ligthart AerCap Colin Merry AerCap Aviation Solutions Joe Dillbeck AerCap Aviation Solutions Diederik Lindhout AerCap B.V. Gary O'Donnell AerCap B.V. Jaap van Dijk AerData Fred Browne AERGO Group Paul Jackson Aero Capital Solutions, Inc. Neal Crispin Aero Century Corporation Oliver Brown Aero Connect John Titus Aero Controls, Inc. Alex Lallanilla Aero Direct, Inc. Brad Goering Aero Direct, Inc. Brian Longmeyer Aero Direct, Inc. Chris Corcoran Aero Direct, Inc. David Durham Aero Direct, Inc. Heidi Lichtenberger Aero Direct, Inc. Karen Currin Aero Direct, Inc. Steve Berner Aero Direct, Inc. Kreg Doerr Aero Intelligence Varghese Samuel Aero Intelligence Peter Metzger Aero Technologies Alison Mason Aerofin Advisors, LLC Jep Thornton Aerolease Aviation LLC Tim Corley Aerolease Aviation LLC Robert Convey Aeronautical Engineers, Inc. -

Group ROW by State of Administration

BELGIUM CRCO Identification no. Operator Name State of the Operator 46463 ACE BELGIUM FREIGHTERS BELGIUM S.A. 31102 ACT AIRLINES TURKEY 38484 AEROTRANSCARGO MOLDOVA, REPUBLIC OF 41049 AHS AIR INT PAKISTAN 7649 AIRBORNE EXPRESS UNITED STATES 33612 ALLIED AIR LIMITED NIGERIA 27011 ASL AIRLINES BELGIUM BELGIUM 31416 AVIA TRAFFIC COMPANY TAJIKISTAN 30020 AVIASTAR-TU CO. RUSSIAN FEDERATION 123 Abelag Aviation NV BELGIUM 908 BRUSSELS AIRLINES BELGIUM 25996 CAIRO AVIATION EGYPT 4369 CAL CARGO AIRLINES ISRAEL 29517 CAPITAL AVTN SRVCS NETHERLANDS f11336 CORPORATE WINGS LLC UNITED STATES 32909 CRESAIR UNITED STATES 32432 EGYPTAIR CARGO EGYPT f12977 EXCELLENT INVESTMENT UNITED STATES LLC 32486 FAYARD ENTERPRISES UNITED STATES f11102 FedEx Express Corporate UNITED STATES Aviation 13457 Flying Partners CVBA BELGIUM 29427 Flying Service N.V. BELGIUM 24578 GAFI GENERAL AVIAT MAURITIUS f12983 GREEN DIESEL LLC UNITED STATES 29980 HAINAN AIRLINES (2) CHINA 23700 HEWA BORA AIRWAYS CONGO 28582 INTER WETAIL AG SWITZERLAND 9542 INTL PAPER CY UNITED STATES 27709 KALITTA AIR UNITED STATES 28087 LAS VEGAS CHARTER UNITED STATES 32303 MASTER TOP LINHAS BRAZIL 37066 MERIDIAN (AIRWAYS) BELGIUM 1084 MIL BELGIUM BELGIUM 31207 N604FJ LLC UNITED STATES f11462 N907WS AVIATION LLC UNITED STATES 26688 NEWELL RUBBERMAID UNITED STATES f10341 OfficeMax Inc UNITED STATES 31660 RIPPLEWOOD AVTN UNITED STATES 2344 SAUDIA SAUDI ARABIA 29222 SILVERBACK CARGO RWANDA 39079 SOLARIUS AVIATION UNITED STATES 35334 SONOCO PRODUCTS CO UNITED STATES BELGIUM 26784 SOUTHERN AIR UNITED STATES 38995 STANLEY BLACK&DECKER UNITED STATES 27769 Sea Air BELGIUM 34920 TRIDENT AVIATION SVC UNITED STATES 30011 TUI AIRLINES - JAF BELGIUM 27911 ULTIMATE ACFT SERVIC UNITED STATES 13603 VF CORP UNITED STATES 36269 VF INTERNATIONAL SWITZERLAND 37064 VIPER CLASSICS LTD UNITED KINGDOM f11467 WILSON & ASSOCIATES OF UNITED STATES DELAWARE LLC 37549 YILTAS GROUP TURKEY BULGARIA CRCO Identification no. -

Santa Fe Independent School District

SANTA FE INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT Purchasing Procedures and Vendor Information FORWARD: This information has been compiled as a guide to acquaint vendors and suppliers with District purchasing policies and procedures. Santa Fe Independent School District Purchasing is a part of the Business Department and responsible forthe organization and administration of the purchasing/procurement functions forthe District in accordance with the authority delegated by the Superintendent and Board of Trustees. The primary functionof Purchasing is to meet the product and service needs of the District by: I) Obtaining the best product at the lowest cost to the taxpayer while complying with all federal, state and local laws as well as District policies and guidelines; 2) Achieving a reliable and timely delivery for the requesting school or department; 3) Promoting fair competition among bidders; 4) Insuring an equal opportunityfor all vendors to secure District business; 5) Educating and informing all vendors about District rules, regulations and methodology forthe basis of bid awards; 6) Constantly seeking to identify and implement strategies and techniques that will enhance the level of service and integrity. As a support organization of the District charged with the acquisition of goods and services requested by instructional and administrative departments, Purchasing will functionin a manner consistent with applicable laws, School Board Policies, the Uniform Commercial Code and other sound business practices. Purchasing shares with the Business Department, the responsibility of expending District funds in such a manner that will meet all requirements of the Stale, Federal and District procurement regulations and safeguard the public trust. Effective purchasing is a cooperative venture between Purchasing, campuses and other departments within the district. -

October 2020 Vol

BUSINESS & COMMERCIAL AVIATION ACCELERATING AUTONOMOUS FLIGHT STABLE BY DESIGN WITHER ANALOG NAVAID OCTOBER 2020 $10.00 AviationWeek.com/BCA ALSO IN THIS ISSUE Stable by Design Wither Analog Navaids? Here’s Looking at You Business & Commercial Aviation The Anti- Anti-ice Protection SPECIAL REPORT Accelerating Autonomy Redefi ning low-altitude aircraft and airspace S? OCTOBER 2020 VOL. 116 NO. 9 S? OCTOBER 2020 VOL. 116 NO. Digital Edition Copyright Notice The content contained in this digital edition (“Digital Material”), as well as its selection and arrangement, is owned by Informa. and its affiliated companies, licensors, and suppliers, and is protected by their respective copyright, trademark and other proprietary rights. Upon payment of the subscription price, if applicable, you are hereby authorized to view, download, copy, and print Digital Material solely for your own personal, non-commercial use, provided that by doing any of the foregoing, you acknowledge that (i) you do not and will not acquire any ownership rights of any kind in the Digital Material or any portion thereof, (ii) you must preserve all copyright and other proprietary notices included in any downloaded Digital Material, and (iii) you must comply in all respects with the use restrictions set forth below and in the Informa Privacy Policy and the Informa Terms of Use (the “Use Restrictions”), each of which is hereby incorporated by reference. Any use not in accordance with, and any failure to comply fully with, the Use Restrictions is expressly prohibited by law, and may result in severe civil and criminal penalties. Violators will be prosecuted to the maximum possible extent.