Philosophic Hinduism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"We Will When

SRSTI 740 became Raksasas (giants) . Those who said "We will the Sanaka brothers and the mental sons of Bhrgu, eat him", became Yaksas. (demi-gods). Because of Pulastya, Pulaha, Kratu, Arigiras, Marlci, Daksa, Atri Yaksana (Bhaksana-Food), they got the name Yaksa. and Vasistha, and gave these nine the name Prajapatis Because of the dislike at seeing these creatures the (Lords of Emanation) . Then he created nine women hair had fallen from the head of Brahma. They crept named Khyati, Bhuti, Sambhuti, Ksama, Prlti, Sannati, back again into his head. Because they did 'sarpana' Urja, Anasuya. and Prasuti and gave in marriage (creeping up) they were called sarpas (serpents) and Khyati to Bhrgu, Bhuti to Pulastya, Sambhuti to Pulaha, as they were 'Hina' (fallen) they were called Ahis Ksama to Kratu, Priti to Arigiras, Sannati to Marlci, (serpents) . After this the Lord of creation became Urja to Daksa, Anasuya to Atri and Prasuti to Vasistha. very angry and created some creatures. Because of The great hermits such as Sanandana and the others their colour which was a mingling of red and black, created before the Prajapatis, were not desirous of pro- they were horrible and they became pisitaSanas (those pagation as they were wise sages who had renounced who eat flesh). Then Brahma began to sing and from all attachments and who had been indifferent. When his body the Gandharvas were born. Because they did Brahma saw that they were not mindful about produc- of 'dhayana' (Appreciate) 'go' (word) when they were ing subjects he grew angry. (It was from the middle of were called born, they Gandharvas. -

Bhoga-Bhaagya-Yogyata Lakshmi

BHOGA-BHAAGYA-YOGYATA LAKSHMI ( FULFILLMENT AS ONE DESERVES) Edited, compiled, and translated by VDN Rao, Retd. General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, currently at Chennai 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu Essence of Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana Essence of Paraashara Smtiti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Dharma Bindu Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and Austerities- Essence of Manu Smriti*- Quintessence of Manu Smriti* - *Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskara- Essence of Maha Narayanopanishad*-Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi* Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www. -

Modern-Baby-Names.Pdf

All about the best things on Hindu Names. BABY NAMES 2016 INDIAN HINDU BABY NAMES Share on Teweet on FACEBOOK TWITTER www.indianhindubaby.com Indian Hindu Baby Names 2016 www.indianhindubaby.com Table of Contents Baby boy names starting with A ............................................................................................................................... 4 Baby boy names starting with B ............................................................................................................................. 10 Baby boy names starting with C ............................................................................................................................. 12 Baby boy names starting with D ............................................................................................................................. 14 Baby boy names starting with E ............................................................................................................................. 18 Baby boy names starting with F .............................................................................................................................. 19 Baby boy names starting with G ............................................................................................................................. 19 Baby boy names starting with H ............................................................................................................................. 22 Baby boy names starting with I .............................................................................................................................. -

1. CAT Exam Schedule on 11/04/2021 and Will Be Held at Anushaktinagar, Mumbai

BHABHA ATOMIC RESEARCH CENTRE ADVERTISMENT No. 04/2020 (R-V) Instructions to M.Sc (NMMIT & HRP) courses candidates 1. CAT exam schedule on 11/04/2021 and will be held at Anushaktinagar, Mumbai. 2. List of candidates available on BARC website recruit.barc.gov.in / www.barc.gov.in 3. CAT exam is same for both the courses. Candidate who applied for more than one course will be called for CAT exam for only one course. 4. Admit card will be issued on or after 30/03/2021. 5. Candidates are required to bring the Admit card and a Photo Identity proof on the day of CAT exam. 6. Candidates required to report at venue of CAT exam at 10.30 a.m. CAT exam will be held from 11.00 a.m. to 01.00 p.m. 7. On the date of CAT exam, sponsored candidates will required to bring sponsorship letter/copy of the sponsorship letter from their organization. Stipend is not admissible to Sponsored candidates. 8. If sponsored candidate fail to bring the sponsorship letter, He/ She will be placed as Non-sponsored candidate subject to fulfillment of all criteria of Non- sponsored candidates. 9. No accommodation will be provided to candidates who are attending CAT exam. 10. No TA is admissible to candidates attending CAT exam. 11. Counseling of CAT exam qualified candidates and subsequent Medical Examination will be held tentatively in June 2021. 12. All CAT exam qualified candidates will be required to bring all original documents (marksheets/certificates etc.) along with Xerox copies of the same for the counseling session. -

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings & Speeches Vol. 4

Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (14th April 1891 - 6th December 1956) BLANK DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR WRITINGS AND SPEECHES VOL. 4 Compiled by VASANT MOON Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar : Writings and Speeches Vol. 4 First Edition by Education Department, Govt. of Maharashtra : October 1987 Re-printed by Dr. Ambedkar Foundation : January, 2014 ISBN (Set) : 978-93-5109-064-9 Courtesy : Monogram used on the Cover page is taken from Babasaheb Dr. Ambedkar’s Letterhead. © Secretary Education Department Government of Maharashtra Price : One Set of 1 to 17 Volumes (20 Books) : Rs. 3000/- Publisher: Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India 15, Janpath, New Delhi - 110 001 Phone : 011-23357625, 23320571, 23320589 Fax : 011-23320582 Website : www.ambedkarfoundation.nic.in The Education Department Government of Maharashtra, Bombay-400032 for Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Source Material Publication Committee Printer M/s. Tan Prints India Pvt. Ltd., N. H. 10, Village-Rohad, Distt. Jhajjar, Haryana Minister for Social Justice and Empowerment & Chairperson, Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Kumari Selja MESSAGE Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the Chief Architect of Indian Constitution was a scholar par excellence, a philosopher, a visionary, an emancipator and a true nationalist. He led a number of social movements to secure human rights to the oppressed and depressed sections of the society. He stands as a symbol of struggle for social justice. The Government of Maharashtra has done a highly commendable work of publication of volumes of unpublished works of Dr. Ambedkar, which have brought out his ideology and philosophy before the Nation and the world. In pursuance of the recommendations of the Centenary Celebrations Committee of Dr. -

Balabhavan Class

October 2009 BBC Announcements: Balabhavan Coordinators SAGE BHRIGU Bharathy Thridandam Navarathri was observed with Nithya Sudhakar the BB children invoking the Sriram Srinivasan blessings of Goddess Saraswathi by their sweet [email protected] rendition of the bhajans, Class Coordinators shlokas and prayers lead by Panditjis. The festive display Super-Senior Class: of the kolu at the temple by Sudhakar Devulapalli: Srinivas Varadarajan and [email protected] family is highly creative and Ashok Malavalli: much admired. [email protected] th Ram Krishnamurthy: October 10 : Please note [email protected] that the parent meeting will be held at the temple main Senior Class: Maharshi Bhrigu was one of the hall between 4:00-5:00 p.m. Renuka Krishnan: Manasputras (born by a wish) of Lord Brahma We request that at least one [email protected] (It is said that he was born from the heart parent from each family be Anitha Chidambaram: part). Sage Narada, Vasishtha, Atri, Gautama present and please be [email protected] etc. were others. Bhrigu is considered as one prompt as there are a lot of of the Nine Brahmas. He was married to Khyati items on the agenda that Junior Class: (the daughter of Daksha), Puloma (daughter of need to be covered. Seetha Janakiraman: Kardama) and Usana. Two sons, Dhata and [email protected] Vidhata and a daughter Shri were born to Re-registrations in October: Sangeetha Prahalad: Khyati. Maharshi Bhrigu is also called Prajapati Current BB children need to [email protected] (creator) as he was created by Lord Brahma to be re-registered. -

Films 2018.Xlsx

List of feature films certified in 2018 Certified Type Of Film Certificate No. Title Language Certificate No. Certificate Date Duration/Le (Video/Digita Producer Name Production House Type ngth l/Celluloid) ARABIC ARABIC WITH 1 LITTLE GANDHI VFL/1/68/2018-MUM 13 June 2018 91.38 Video HOUSE OF FILM - U ENGLISH SUBTITLE Assamese SVF 1 AMAZON ADVENTURE Assamese DIL/2/5/2018-KOL 02 January 2018 140 Digital Ravi Sharma ENTERTAINMENT UA PVT. LTD. TRILOKINATH India Stories Media XHOIXOBOTE 2 Assamese DIL/2/20/2018-MUM 18 January 2018 93.04 Digital CHANDRABHAN & Entertainment Pvt UA DHEMALITE. MALHOTRA Ltd AM TELEVISION 3 LILAR PORA LEILALOI Assamese DIL/2/1/2018-GUW 30 January 2018 97.09 Digital Sanjive Narain UA PVT LTD. A.R. 4 NIJANOR GAAN Assamese DIL/1/1/2018-GUW 12 March 2018 155.1 Digital Haider Alam Azad U INTERNATIONAL Ravindra Singh ANHAD STUDIO 5 RAKTABEEZ Assamese DIL/2/3/2018-GUW 08 May 2018 127.23 Digital UA Rajawat PVT.LTD. ASSAMESE WITH Gopendra Mohan SHIVAM 6 KAANEEN DIL/1/3/2018-GUW 09 May 2018 135 Digital U ENGLISH SUBTITLES Das CREATION Ankita Das 7 TANDAB OF PANDAB Assamese DIL/1/4/2018-GUW 15 May 2018 150.41 Digital Arian Entertainment U Choudhury 8 KRODH Assamese DIL/3/1/2018-GUW 25 May 2018 100.36 Digital Manoj Baishya - A Ajay Vishnu Children's Film 9 HAPPY MOTHER'S DAY Assamese DIL/1/5/2018-GUW 08 June 2018 108.08 Digital U Chavan Society, India Ajay Vishnu Children's Film 10 GILLI GILLI ATTA Assamese DIL/1/6/2018-GUW 08 June 2018 85.17 Digital U Chavan Society, India SEEMA- THE UNTOLD ASSAMESE WITH AM TELEVISION 11 DIL/1/17/2018-GUW 25 June 2018 94.1 Digital Sanjive Narain U STORY ENGLISH SUBTITLES PVT LTD. -

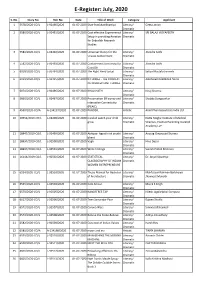

E-Register: July, 2020

E-Register: July, 2020 S. No. Diary No. RoC No. Date Title of Work Category Applicant 1 5578/2020-CO/L L-92490/2020 01-07-2020 Shat-Pratishat Bhartiya Literary/ Geeta Atrish Dramatic 2 5580/2020-CO/L L-92491/2020 01-07-2020 Cost effective Experimental Literary/ SRI BALAJI VIDYAPEETH Setup in providing Aeration Dramatic for Zebrafish Research Studies 3 5581/2020-CO/L L-92492/2020 01-07-2020 Universal theory for the Literary/ Jitendra Sethi viruses containment Dramatic 4 5582/2020-CO/L L-92493/2020 01-07-2020 Containment tomorrow for Literary/ Jitendra Sethi Covid19 Dramatic 5 6018/2020-CO/L L-92494/2020 01-07-2020 The Right Hand to Eat Literary/ Safiya Mustafa Jariwala Dramatic 6 6019/2020-CO/L L-92495/2020 01-07-2020 D TUNNEL - THE CONCEPT Literary/ ABHISHEK RABINDER NATH OF DISINFECTANT TUNNEL Dramatic 7 6071/2020-CO/L L-92496/2020 01-07-2020 KHALI HATH Literary/ Niraj Sharma Dramatic 8 5860/2020-CO/L L-92497/2020 01-07-2020 Preservation Efficiency and Literary/ Shabda Dongaonkar interactive Connectivity Dramatic (PEAIC) 9 4530/2020-CO/A A-134197/2020 01-07-2020 PURODIL Artistic Aimil Pharmaceuticals India Ltd. 10 20554/2019-CO/L L-92498/2020 01-07-2020 icarekid watch your child Literary/ Datta Meghe Institute of Medical grow Dramatic Sciences ,Positive Parenting iCareKid Academy LLP 11 18947/2019-CO/L L-92499/2020 01-07-2020 Abhipsa- Agyat ki ek anuthi Literary/ Anurag Omprasad Sharma bhent Dramatic 12 18937/2019-CO/L L-92500/2020 01-07-2020 Vagh Literary/ Hina Desai Dramatic 13 18917/2019-CO/L L-92501/2020 01-07-2020 Write Feelings Literary/ Suresh Pattali Krishnan Dramatic 14 16114/2019-CO/L L-92502/2020 01-07-2020 STATISTICAL Literary/ Dr. -

Riddles in Hinduism

Bharat Ratna Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar "Father Of Indian Constitution" India’s first Law Minister Architect of the Constitution of India ii http://www.ambedkar.org Born April 14, 1891, Mhow, India Died Dec. 6, 1956, New Delhi Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, was the first Minister of Law soon after the Independence of India in 1947 and was the Chairman of the drafting committee for the Constitution of India As such he was chiefly responsible for drafting of The Constitution of India. Ambedkar was born on the 14 th April, 1891. After graduating from Elphinstone College, Bombay in 1912, he joined Columbia University, USA where he was awarded Ph.D. Later he joined the London School of Economics & obtained a degree of D.Sc. ( Economics) and was called to the Bar from Gray's Inn. He returned to India in 1923 and started the 'Bahishkrit Hitkarini Sabha' for the education and economic improvement of the lower classes from where he came. One of the greatest contributions of Dr. Ambedkar was in respect of Fundamental Rights & Directive Principles of State Policy enshrined in the Constitution of India. The Fundamental Rights provide for freedom, equality, and abolition of Untouchability & remedies to ensure the enforcement of rights. The Directive Principles enshrine the broad guiding principles for securing fair distribution of wealth & better living conditions. On the 14 th October, 1956, Babasaheb Ambedkar a scholar in Hinduism embraced Buddhism. He continued the crusade for social revolution until the end of his life on the 6th December 1956. He was honoured with the highest national honour, 'Bharat Ratna' in April 1990 . -

Spring 2021 TE TA UN S E ST TH at I F E V a O O E L F a DITAT DEUS

Commencement 2021 Spring 2021 TE TA UN S E ST TH AT I F E V A O O E L F A DITAT DEUS N A E R R S I O Z T S O A N Z E I A R I T G R Y A 1912 1885 ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY COMMENCEMENT AND CONVOCATION PROGRAM Spring 2021 May 3, 2021 THE NATIONAL ANTHEM CONTENTS THE STAR-SPANGLED BANNER The National Anthem and O say can you see, by the dawn’s early light, Arizona State University Alma Mater ................................. 2 What so proudly we hailed at the twilight’s last gleaming? Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight Letter of Congratulations from the Arizona Board of Regents ............... 5 O’er the ramparts we watched, were so gallantly streaming? History of Honorary Degrees .............................................. 6 And the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there. Past Honorary Degree Recipients .......................................... 6 O say does that Star-Spangled Banner yet wave Conferring of Doctoral Degrees ............................................ 9 O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave? Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law Convocation ....................... 29 ALMA MATER Conferring of Masters Degrees ............................................ 36 ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY Craig and Barbara Barrett Honors College ................................102 Where the bold saguaros Moeur Award ............................................................137 Raise their arms on high, Praying strength for brave tomorrows Graduation with Academic Recognition ..................................157 From the western sky; Summa Cum Laude, 157 Where eternal mountains Magna Cum Laude, 175 Kneel at sunset’s gate, Cum Laude, 186 Here we hail thee, Alma Mater, Arizona State. -

Student Strength

STUDENT STRENGTH GRADE/SECTION:IV/ALPHA GRADE/SECTION:IV/BETA CLASS TEACHER : SHALINI SETH CLASS TEACHER : GISHA MARY MATHEW SL.NO STUDENT NAME SL.NO STUDENT NAME 1 Akshaj Nalam 1 MUDDANA VENKATA ABHINAV 2 Anik Rangisetty 2 JAYANSH KANNAM 3 Betha Tanvi 3 B. Shriyan Goud 4 Darshwana Kiran Balusu 4 Rachamalla Ritika 5 Diyaan Darsh 5 NIHAL REDDY KESIREDDY 6 Gandhavarapu Harika 6 VIKHYATH RAO GOTTUMUKKALA 7 Hishitha Vattikuti 7 SAI ADVAITH GUDIPATI 8 Kandukuri Sai Gaurav 8 MANKALA BADRINATH 9 Karthikeya. R 9 KRITHIKA NERA 10 Kushal Tadapaneni 10 Rishikesh 11 Manish M Wadekar 11 CH VN MOHITH REDDY 12 Manotej Reddy 12 VISKABAI PRATAP REDDY 13 Naga Rushikesh Avadanam 13 HAVALADA KARTIKEYA 14 Nithya Sri Sai Jampana 14 Naga Krishna Sahasra 15 P. Dikshith Reddy 15 SRI CHARAN KUMAR REDDY 16 P. Omkar Reddy 16 JAYANTHI NARASIMHA ADHRITH 17 RAMINENI DHANYA BHAVATHARINI 17 Samhita Chitturi 18 Rithika Tripuraneni 18 Jahnavi Kasani 19 SAMMETA DAKSHA 19 Gandham Sai Lakshmi Deekshita 20 Sriamsh Jay Kandoti 20 RUHAAN ANDREI MUNI 21 Sudhith Singh Rawat 21 DEBANSH NAYAK 22 Surisetty Vedanshi 22 Esha Parnika 23 Umesh Mantrapudi 23 NANDIKONDA SIDDHARTH REDDY 24 VEDA MANISH 24 SRI RAM SIDDHARTHA MATHI STUDENT STRENGTH GRADE/SECTION:IV/GAMMA GRADE/SECTION:IV/DELTA CLASS TEACHER : SHARADA CLASS TEACHER : CHANDI SL.NO STUDENT NAME SL.NO STUDENT NAME 1 RUDHIRA KRISHNA KALE 1 V. Harshita 2 Kolachina Shresta Sarvani 2 NIHIL YERUVA 3 Jandhyala Shreyash 3 KAMIREDDI GUNEETHSATHYA 4 K.BHAVITA 4 M.HARMAN CHAITANYA 5 KONA KANAK DURGA 5 RUSHANTH PINNAMANENI 6 M VISHNU DATTA -

Hindu Mythology, Vedic and Purānic

- -; :-\j«»'S!^'^wrr!»i« INDIANA UNIVERSITY LIBRARY <5 Co T&acKer , Ltd., Bombay Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Indiana University http://www.archive.org/details/hindumythologyveOOinwilk HINDU MYTHOLOGY. DURGA. Lakshmi. Sarasvati. Ganesa. The Demon Kartikeya. Durga. HINDU MYTHOLOGY VEDIC AND PURANIC BY W. J WILKINS LATE OF THE LONDON MISSIONARY SOCIETY CALCUTTA AUTHOR OK "MODERN HINDUISM," ETC ILLUSTRATED THIRD IMPRESSION t 6 llClt CALCUTTA AND SIMLA THACKER, SPINK & CO London : W. THACKER & CO., 2, CREED LANE, E.C 1913- _IZO .W58 Calcutta : Printed by Thackkr, Spink and Co. [The tight of translation is reserved.] INDIANA UNIVERSITY: LIBRAR2 PREFACE. On reaching India, one of my first inquiries was for a full and trustworthy account of the mythology of the Hindus ; but though I read various works in which some information of the kind was to be found, I sought in vain for a complete and systematic work on this subject. Since then two classical dictionaries of India have been published, one in Madras and one in London ; but though useful books of reference, they do not meet the want that this book is intended to supply. For some years I have been collecting materials with the intention of arranging them in such a way that any one without much labour might gain a good general idea of the names, character, and relation- ship of the principal deities of Hinduism. This work does not profess to supply new translations of the Hindu Scriptures, nor to give very much information that is not already scattered through many other books.