Temperature Relationships of Great Lakes Fishes: By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sanitization: Concentration, Temperature, and Exposure Time

Sanitization: Concentration, Temperature, and Exposure Time Did you know? According to the CDC, contaminated equipment is one of the top five risk factors that contribute to foodborne illnesses. Food contact surfaces in your establishment must be cleaned and sanitized. This can be done either by heating an object to a high enough temperature to kill harmful micro-organisms or it can be treated with a chemical sanitizing compound. 1. Heat Sanitization: Allowing a food contact surface to be exposed to high heat for a designated period of time will sanitize the surface. An acceptable method of hot water sanitizing is by utilizing the three compartment sink. The final step of the wash, rinse, and sanitizing procedure is immersion of the object in water with a temperature of at least 170°F for no less than 30 seconds. The most common method of hot water sanitizing takes place in the final rinse cycle of dishwashing machines. Water temperature must be at least 180°F, but not greater than 200°F. At temperatures greater than 200°F, water vaporizes into steam before sanitization can occur. It is important to note that the surface temperature of the object being sanitized must be at 160°F for a long enough time to kill the bacteria. 2. Chemical Sanitization: Sanitizing is also achieved through the use of chemical compounds capable of destroying disease causing bacteria. Common sanitizers are chlorine (bleach), iodine, and quaternary ammonium. Chemical sanitizers have found widespread acceptance in the food service industry. These compounds are regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and consequently require labeling with the word “Sanitizer.” The labeling should also include what concentration to use, data on minimum effective uses and warnings of possible health hazards. -

The Effect of Carbon Monoxide Sources and Meteorologic Changes in Carbon Monoxide Intoxication: a Retrospective Study

Cilt: 3 Sayı: 1 Şubat 2020 / Vol: 3 Issue: 1 February 2020 https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/actamednicomedia Research Article | Araştırma Makalesi THE EFFECT OF CARBON MONOXIDE SOURCES AND METEOROLOGIC CHANGES IN CARBON MONOXIDE INTOXICATION: A RETROSPECTIVE STUDY KARBONMONOKSİT KAYNAKLARININ VE METEOROLOJİK DEĞİŞİKLİKLERİN KARBONMONOKSİT ZEHİRLENMELERİNE ETKİSİ: RETROSPEKTİF ÇALIŞMA Duygu Yılmaz1, Umut Yücel Çavuş2, Sinan Yıldırım3, Bahar Gülcay Çat Bakır4*, Gözde Besi Tetik5, Onur Evren Yılmaz6, Mehtap Kaynakçı Bayram7 1Manisa Turgutlu State Hospital, Department of Emergency Medicine, Manisa, Turkey. 2Ankara Education and Research Hospital, Department of Emergency Medicine, Ankara, Turkey. 3Çanakkale State Hospital, Department of Emergency Medicine, Çanakkale,Turkey. 4Mersin City Education and Research Hospital, Department of Emergency Medicine, Mersin, Turkey. 5Gaziantep Şehitkamil State Hospital, Department of Emergency Medicine, Gaziantep, Turkey. 6Medical Park Hospital, Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, İzmir, Turkey. 7Kayseri City Education and Research Hospital, Department of Emergency Medicine, Kayseri, Turkey. ABSTRACT ÖZ Objective: Carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning is frequently seen in Amaç: Karbonmonoksit (CO) zehirlenmelerine, özellikle soğuk emergency departments (ED) especially in cold weather. We havalarda olmak üzere acil servis birimlerinde sıklıkla karşılaşılır. investigated the relationship of some of the meteorological factors Çalışmamızda, bazı meteorolojik faktörlerin CO zehirlenmesinin with the sources -

Sea Surface Temperatures on the Great Barrier Reef: a Contribution to the Study of Coral Bleaching

GREAT BARRIER REEF MARINE PARK AUTHORITY RESEARCH PUBLICATION No. 57 Sea Surface Temperatures on the Great Barrier Reef: a Contribution to the Study of Coral Bleaching JM Lough 551.460 109943 1999 RESEARCH PUBLICATION No. 57 Sea Surface Temperatures on the Great Barrier Reef: a Contribution to the Study of Coral Bleaching JM Lough Australian Institute of Marine Science AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE GREAT BARRIER REEF OF MARINE SCIENCE MARINE PARK AUTHORITY A REPORT TO THE GREAT BARRIER REEF MARINE PARK AUTHORITY O Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Australian Institute of Marine Science 1999 ISSN 1037-1508 ISBN 0 642 23069 2 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority and the Australian Institute of Marine Science. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Director, Information Support Group, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, PO Box 1379, Townsville Qld 4810. The opinions expressed in this document are not necessarily those of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. Accuracy in calculations, figures, tables, names, quotations, references etc. is the complete responsibility of the author. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication data: Lough, J. M. Sea surface temperatures on the Great Barrier Reef : a contribution to the study of coral bleaching. Bibliography. ISBN 0 642 23069 2. 1. Ocean temperature - Queensland - Great Barrier Reef. 2. Corals - Queensland - Great Barrier Reef - Effect of temperature on. 3. Coral reef ecology - Australia - Great Barrier Reef (Qld.) - Effect of temperature on. -

INFLUENCE of TEMPERATURE on DIFFUSION and SORPTION of 237Np(V) THROUGH BENTONITE ENGINEERED BARRIERS

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2017 Influence of emperT ature on Diffusion and Sorption of 237Np(V) through Bentonite Engineered Barriers Rachel Nicole Pope Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Pope, Rachel Nicole, "Influence of emperT ature on Diffusion and Sorption of 237Np(V) through Bentonite Engineered Barriers" (2017). All Theses. 2666. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2666 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFLUENCE OF TEMPERATURE ON DIFFUSION AND SORPTION OF 237Np(V) THROUGH BENTONITE ENGINEERED BARRIERS A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Environmental Engineering and Earth Sciences by Rachel Nicole Pope May 2017 Accepted by: Dr. Brian A. Powell, Committee Chair Dr. Mark Schlautman Dr. Lindsay Shuller‐Nickles ABSTRACT Diffusion rates of 237Np(V), 3H, and 22Na through Na‐montmorillonite were studied under variable dry bulk density and temperature. Distribution coefficients were extrapolated for conservative tracers. Two sampling methods were implemented, and effects of each sampling method were compared. The first focused on an exchange of the lower concentration reservoir frequently while the second kept the lower concentration reservoir consistent. In both sampling methods, tritium diffusion coefficients decreased with an increase in dry bulk density and increased with an increase in temperature. Sodium diffusion rates followed the same trends as tritium with the exception of sorption phenomena. -

The Application of Temperature And/Or Pressure Correction Factors in Gas Measurement COMBINED BOYLE’S – CHARLES’ GAS LAWS

The Application of Temperature and/or Pressure Correction Factors in Gas Measurement COMBINED BOYLE’S – CHARLES’ GAS LAWS To convert measured volume at metered pressure and temperature to selling volume at agreed base P1 V1 P2 V2 pressure and temperature = T1 T2 Temperatures & Pressures vary at Meter Readings must be converted to Standard conditions for billing Application of Correction Factors for Pressure and/or Temperature Introduction: Most gas meters measure the volume of gas at existing line conditions of pressure and temperature. This volume is usually referred to as displaced volume or actual volume (VA). The value of the gas (i.e., heat content) is referred to in gas measurement as the standard volume (VS) or volume at standard conditions of pressure and temperature. Since gases are compressible fluids, a meter that is measuring gas at two (2) atmospheres will have twice the capacity that it would have if the gas is being measured at one (1) atmosphere. (Note: One atmosphere is the pressure exerted by the air around us. This value is normally 14.696 psi absolute pressure at sea level, or 29.92 inches of mercury.) This fact is referred to as Boyle’s Law which states, “Under constant tempera- ture conditions, the volume of gas is inversely proportional to the ratio of the change in absolute pressures”. This can be expressed mathematically as: * P1 V1 = P2 V2 or P1 = V2 P2 V1 Charles’ Law states that, “Under constant pressure conditions, the volume of gas is directly proportional to the ratio of the change in absolute temperature”. Or mathematically, * V1 = V2 or V1 T2 = V2 T1 T1 T2 Gas meters are normally rated in terms of displaced cubic feet per hour. -

Boyle's Law Apparatus 1017366 (U172101) Distance S Travelled by the Piston Relative to the Zero-Volume Position

Heat Gas Laws Boyle’s Law MEASUREMENTS ON AIR AT ROOM TEMPERATURE Measuring the pressure p of the enclosed air at room temperature for different positions s of the piston. Displaying the measured values for three different quantities of air in the form of a p-V diagram. Verifying Boyle’s Law. UE2040100 04/16 JS BASIC PRINCIPLES The volume of a fixed quantity of a gas depends on the From the general equation (2), the special case (1) is derived pressure acting on the gas and on the temperature of the given the condition that the temperature T and the quantity of gas. If the temperature remains unchanged, the product the gas n do not change. of the volume and the temperature remains constant in many cases. This law, discovered by Robert Boyle and In the experiment, the validity of Boyle’s Law at room Edme Mariotte, is valid for all gases in the ideal state, temperature is demonstrated by taking air as an ideal gas. which is when the temperature of the gas is far above the The volume V of air in a cylindrical vessel is varied by the point that is called its critical temperature. movement of a piston, while simultaneously measuring the pressure p of the enclosed air. The law discovered by Boyle und Mariotte states that : The quantity n of the gas depends on the initial volume V0 into (1) p V const. which the air is admitted through an open valve before starting the experiment. and is a special case of the more general law that applies to all ideal gases. -

Air Pressure and Wind

Air Pressure We know that standard atmospheric pressure is 14.7 pounds per square inch. We also know that air pressure decreases as we rise in the atmosphere. 1013.25 mb = 101.325 kPa = 29.92 inches Hg = 14.7 pounds per in 2 = 760 mm of Hg = 34 feet of water Air pressure can simply be measured with a barometer by measuring how the level of a liquid changes due to different weather conditions. In order that we don't have columns of liquid many feet tall, it is best to use a column of mercury, a dense liquid. The aneroid barometer measures air pressure without the use of liquid by using a partially evacuated chamber. This bellows-like chamber responds to air pressure so it can be used to measure atmospheric pressure. Air pressure records: 1084 mb in Siberia (1968) 870 mb in a Pacific Typhoon An Ideal Ga s behaves in such a way that the relationship between pressure (P), temperature (T), and volume (V) are well characterized. The equation that relates the three variables, the Ideal Gas Law , is PV = nRT with n being the number of moles of gas, and R being a constant. If we keep the mass of the gas constant, then we can simplify the equation to (PV)/T = constant. That means that: For a constant P, T increases, V increases. For a constant V, T increases, P increases. For a constant T, P increases, V decreases. Since air is a gas, it responds to changes in temperature, elevation, and latitude (owing to a non-spherical Earth). -

Aircraft Performance: Atmospheric Pressure

Aircraft Performance: Atmospheric Pressure FAA Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge Chap 10 Atmosphere • Envelope surrounds earth • Air has mass, weight, indefinite shape • Atmosphere – 78% Nitrogen – 21% Oxygen – 1% other gases (argon, helium, etc) • Most oxygen < 35,000 ft Atmospheric Pressure • Factors in: – Weather – Aerodynamic Lift – Flight Instrument • Altimeter • Vertical Speed Indicator • Airspeed Indicator • Manifold Pressure Guage Pressure • Air has mass – Affected by gravity • Air has weight Force • Under Standard Atmospheric conditions – at Sea Level weight of atmosphere = 14.7 psi • As air become less dense: – Reduces engine power (engine takes in less air) – Reduces thrust (propeller is less efficient in thin air) – Reduces Lift (thin air exerts less force on the airfoils) International Standard Atmosphere (ISA) • Standard atmosphere at Sea level: – Temperature 59 degrees F (15 degrees C) – Pressure 29.92 in Hg (1013.2 mb) • Standard Temp Lapse Rate – -3.5 degrees F (or 2 degrees C) per 1000 ft altitude gain • Upto 36,000 ft (then constant) • Standard Pressure Lapse Rate – -1 in Hg per 1000 ft altitude gain Non-standard Conditions • Correction factors must be applied • Note: aircraft performance is compared and evaluated with respect to standard conditions • Note: instruments calibrated for standard conditions Pressure Altitude • Height above Standard Datum Plane (SDP) • If the Barometric Reference Setting on the Altimeter is set to 29.92 in Hg, then the altitude is defined by the ISA standard pressure readings (see Figure 10-2, pg 10-3) Density Altitude • Used for correlating aerodynamic performance • Density altitude = pressure altitude corrected for non-standard temperature • Density Altitude is vertical distance above sea- level (in standard conditions) at which a given density is to be found • Aircraft performance increases as Density of air increases (lower density altitude) • Aircraft performance decreases as Density of air decreases (higher density altitude) Density Altitude 1. -

Ph Temperature Compensation

pH Temperature Compensation There are two types of temperature compensation when discussing pH measurements. Automatic Temperature Compensation (ATC), which compensates for the varying milli-volt output from the electrode due to temperature changes of the process solution and Solution Temperature Compensation (STC), which corrects for a change in the chemistry (change in pH) of the solution as the temperature of the solution changes. Automatic Temperature Compensation In a pH-measuring loop, there are three main components. The glass (pH) measuring electrode, the reference electrode and the temperature electrode. When the electrodes are placed in a solution, a voltage (mV) is generated depending on the hydrogen activity of the solution. The varying voltage (potential) is dependent on the acidity or alkalinity of the solution and varies with the hydrogen ion activity in a known manner, the Nernst Equation. The potential (voltage) of the glass electrode is compared to the potential of the reference electrode and the difference between the two potentials is the measured potential. When placed in a pH 7 buffer most electrodes are designed to produce a zero (0) mV potential. As the solution becomes more acidic (lower pH) the potential of the glass electrode becomes more positive (+ mV) in comparison to the reference electrode and as the solution becomes more alkaline (higher pH) the potential of the glass electrode becomes more negative (- mV) in comparison to the reference electrode. The Nernst Equation shows the relationship between temperature and its affect on the activity of the hydrogen ion. At 25°C, each additional pH unit change represents a +/- 59.16 mV change in the potential of the glass electrode from a starting point of pH 7 (0 mV). -

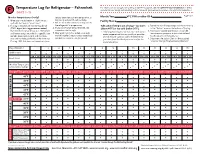

Temperature Log for Refrigerator -- Fahrenheit

Temperature Log for Refrigerator – Fahrenheit For information on storage and handling of COVID-19 vaccines, see the COVID-19 Vaccine Addendum in CDC’s ° updated Vaccine Storage and Handling Toolkit at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/admin/storage/toolkit/index.html. F DAYS 1–15 / Page 1 of 2 Monitor temperatures closely! temps, document current temps twice, at Month Year VFC PIN or other ID # 1. Write your initials below in “Staff Initials,” beginning and end of each workday. Facility Name and note the time in “Exact Time.” 3. Put an “X” in the row that corresponds to 2. If using a temperature monitoring device the refrigerator’s temperature. Take action if temp is out of range – too warm 2. Record the out-of-range temps and the room temp (TMD; digital data logger recommended) 4. If any out-of-range temp observed, see (above 46ºF) or too cold (below 36ºF). in the “Action” area on the bottom of the log. instructions to the right. that records min/max temps (i.e., the highest 1. Label exposed vaccine “do not use,” and store it 3. Notify your vaccine coordinator, or call the 5. After each month has ended, save each and lowest temps recorded in a specific time under proper conditions as quickly as possible. immunization program at your state or local month’s log for 3 years, unless state/local period), document current and min/max Do not discard vaccines unless directed to by health department for guidance. jurisdictions require a longer period. once each workday, preferably in the morning. -

Sea Surface Temperatures on the Great Barrier Reef: a Contribution to the Study of Coral Bleaching

RESEARCH PUBLICATION No. 57 Sea Surface Temperatures on the Great Barrier Reef: a Contribution to the Study of Coral Bleaching JMLough Australian ]nstitute of Marine Science cRc--).., . AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTf .......... Of MARINE SCIENCE A REPORT TO THE GREAT BARRIER REEF MARINE PARK AUTHORITY © Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Australian Institute of Marine Science 1999 ISSN 1037-1508 ISBN 0 642 23069 2 -nuswork is oopyrighl Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright AcI1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Grut Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority and the Australian Institute of Marine Science. Requests and inquiries cof'll:eming reproduction and rights should be: addressed to the Director, Wornuolion Support Croup, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, PO Box 1379, TownsvilleQld 4810. The opinions expressed in this docwnent are not necessarily those ofthe Greal Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. Arouacy in c.alculations. figures, tables, names, quotations, refel"!rlCeS ~c. is the romplete responsibility of the author. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication data: Lough,]. M. Sea surface temperatures on the Great Barrier Reef: a contribution to the study ofcoral bleaching. Bibliography. ISBN 0 64223069 2. 1. Ocean temperature - Queensland - Great Barrier Reef. 2. Corals - Queensland - Great Barrier Reef - Effect of temperature on. 3. Coral reef ecology - Australia - Great Barrier Reel (Qld.l - Effect 01 temperature on. 4. Great Barrier Reel (Qld.l. I. Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (Australial. n. TItle. (Series, Research publication (Great Barrier Reel Marine Park Authority (Australia)l ; no. 57). 551.460109943 GREAT BARRIER REEF MARINE PARK AuTHoRrrY PO Box 1379 Townsville Qld 4810 Telephone (07) 4750 0700 CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES iii LIST OF TABLES iv SUMMARy 1 INTRODUCTION 2 DATA....•............................................................................................................................................ -

Temperature Variation and Buffering Solutions

White Paper Temperature Variation and Buffering Solutions White Paper Introduction When encountering two temperature devices with varying readings, people will often question the newer reference rather than an existing indicator – regardless of quality or accuracy. Little is understood by the end-user as to why the device readings do not match. This unfortunately can result in product returns only to discover that the replacement unit acts the same. Why Do Readings Vary? Many factors can cause two devices to give varying temperature readings. In order to determine whether there is actually a problem, there are several things that must be considered, since they are all legitimate reasons for temperature variation: . Probe mass (more mass = slower reaction to change) . Probe placement . Measurement type (surface, air, liquid) . Software averaging and sampling mechanism . Measurement accuracy (tolerance of probe, A/D resolution) In the two test scenarios to follow, you’ll see the dramatic effect of probe mass (using a buffer solution) as well as probe placement. You’ll also see that these both are affected by refrigerator cycling, which also widely varies. The two refrigerators used were monitored under normal use, though a couple forced scenarios were used to see the effect of the temperature when the door is opened. White Paper Temperature Monitoring Test Results: Dorm Fridge Probe Cycling Spans (Undisturbed Cooling) Top Left Top Left Bottom Left Bottom Left Top Right Top Right Bottom Right Bottom Right (Buffered) (Buffered) (Buffered) (Buffered) 1.2°F 0.9°F 0.9°F 0.6°F 4.2°F 1.8°F 3.3°F 1.3°F In all of the above examples, it’s clear that the buffer solution reduces the cycling effect.