Richland Common Pleas Case#2019Cp4004521

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Safe and Secure Distribution of Controlled Substances September 2019 About This Report

Safe and Secure Distribution of Controlled Substances September 2019 About This Report AmerisourceBergen exists within a highly AmerisourceBergen is publishing this report complex and dynamic healthcare environment. both to build on the Company’s commitment to We provide both our partners and the healthcare transparency and to provide stockholders and other system deep scale, efficiency, and value. Our wholesale stakeholders information on our efforts to ensure pharmaceutical distribution business plays a key role the safe and secure distribution of opioids and in the pharmaceutical supply chain, providing safe other controlled substances, as well as information access to thousands of important medications for on the community and associated outreach healthcare providers to serve patients with a wide programs AmerisourceBergen created and supports array of clinical needs across the healthcare spectrum. to help combat the opioid epidemic. This report supplements our efforts to communicate with The driving force behind everything we do is our stakeholders through our Corporate Citizenship Purpose - we are united in our responsibility to create Report, proxy materials, and the Fighting the Opioid healthier futures. This Purpose drives every facet of Epidemic section of our website1 and supports our our business and is more important today than ever ongoing dialogue through direct engagement. as we and the country grapple with the opioid crisis. AmerisourceBergen welcomes the opportunity AmerisourceBergen has a longstanding commitment to provide this information and the Company is to ensuring a safe and efficient pharmaceutical committed to continued transparency. supply chain. We have taken substantial steps to combat the diversion of controlled substances and fight opioid misuse and abuse. -

Effects of Drug Diversion

Drug abuse is not just a problem con- Determining when pain relieving medica- fined to our streets and our schools. It can tions have been diverted from the rightful recip- happen anywhere a person has a problem ients is often problematic. Long term care facili- related to drug addiction. Frequently it can ties use forms to record which medications have occur in places that may not readily come to been given to residents according to the proper mind for most people – our long term care schedule. When the resident, due to his/her ex- facilities such as nursing homes and assisted isting physical or mental disabilities, is unable to living facilities. When caregivers in long term report that medications have not been admin- care facilities steal medications that were law- istered, facility administrators may have to rely fully prescribed for the residents in their care, on the medication administration records alone. it is called drug diversion. The person completing those records may be the same individual who is diverting the drugs for Drug diversion is a criminal act in- his/her own unlawful use. Occasionally the per- volving the unlawful obtaining and posses- son diverting the medications prescribed for the sion of regulated drugs known as Controlled resident will substitute some other type of med- Dangerous Substances (“CDS”) such as ication in order to attempt to make the proper opioids or narcotics. recipient think that he/she was given dosage that is rightfully due (e.g., giving the resident an ac- Effects of Drug Diversion: etaminophen tablet in place of the more effec- tive, prescribed pain medication.) • It endangers the health of patients who do not receive the prescribed medications they need. -

Name Address City Zip AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP

Name Address City Zip AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 322 N 3RD ST PADUCAH 42001 AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 6810 SHADY OAK RD EDEN PRAIRIE 55344 AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 172 CAHABA VALLEY PKY PELHAM 35124 AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 6305 LASALLE DR LOCKBOURNE 43137 AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 501 PATRIOT PKWY ROANOKE 76262 AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 1001 W TAYLOR RD ROMEOVILLE 60446 AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 11200 NORTH CONGRESS AVE KANSAS CITY 64153 AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 5100 JAINDL BLVD BETHLEHEM 18017 AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 004 101 NORFOLK ST MANSFIELD 2048 AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 008 1325 W STRIKER AVE SACRAMENTO 95834‐1164 AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 012 1851 CALIFORNIA AVE CORONA 92881 AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 017 1765 FREMONT DR SALT LAKE CITY 84104 AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 020 1825 S 43RD AVE PHOENIX 85009 AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 024 24903 AVE KEARNY VALENCIA 91355 AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 026 238 SAND ISLAND ACCESS RD #M‐1 HONOLULU 96819 AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 032 19220 64TH AVE SOUTH KENT 98032 AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 037 12727 W AIRPORT BLVD SUGAR LAND 77478 AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 038 501 W 44TH AVE DENVER 80216 AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 040 1085 N SATELLITE BLVD SUWANEE 30024 AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 041 9900 JEB STUART PKWY GLEN ALLEN 23059 AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 049 ONE INDUSTRIAL PARK DR WILLIAMSTON 48895 AMERISOURCEBERGEN DRUG CO 120 TRANS AIR DR MORRISVILLE 27560 AMERISOURCEBERGEN DRUG CORP 2100 DIRECTORS ROW ORLANDO 32809‐6234 AMERISOURCEBERGEN DRUG CORP 10910 VISTA BLVD SUITE 401 ORLANDO 32829 ASD SPECIALTY HEALTHCARE ABC 345 INTERNATIONAL BLVD STE 400 BROOKS 40109 -

In Brief, Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs: a Guide for Healthcare Providers

In Brief Winter 2017 • Volume 10 • Issue 1 Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs: A Guide for Healthcare Providers Since the 1990s, a dramatic increase in prescriptions The Evolution of PDMPs for controlled medications—particularly for opioid pain PDMPs are state-operated databases that collect relievers such as oxycodone and hydrocodone—has information on dispensed medications. The first PDMP been paralleled by an increase in their misuse1 and by was established in 1939 in California, and by 1990 another an escalation of overdose deaths related to opioid pain eight state programs had been established.4 PDMPs would relievers.2 The number of state-run prescription drug periodically send reports to law enforcement, regulatory, monitoring programs (PDMPs) has also increased during or licensing agencies as part of efforts to control diversion this timeframe. Currently, 49 states, the District of of medication by prescribers, pharmacies, and organized Columbia, and 1 U.S. territory (Guam) have criminals. Such diversion can occur through medication or operational PDMPs. prescription theft or illicit selling, prescription forgery or The first state PDMPs provided law enforcement and other counterfeiting, nonmedical prescribing, and other means, public agencies with surveillance data to identify providers including diversion schemes associated with sleep clinics inappropriately prescribing controlled medications. The (sedative-hypnotics and barbiturates), weight clinics objective was to minimize harmful and illegal use and (stimulants), and pain -

Legal Authorities Under the Controlled Substances Act to Combat the Opioid Crisis

Legal Authorities Under the Controlled Substances Act to Combat the Opioid Crisis Updated December 18, 2018 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45164 Legal Authorities Under the Controlled Substances Act to Combat the Opioid Crisis Summary According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the annual number of drug overdose deaths involving prescription opioids (such as hydrocodone, oxycodone, and methadone) and illicit opioids (such as heroin and nonpharmaceutical fentanyl) has more than quadrupled since 1999. A November 2017 report issued by the President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis also observed that “[t]he crisis in opioid overdose deaths has reached epidemic proportions in the United States ... and currently exceeds all other drug-related deaths or traffic fatalities.” How the current opioid epidemic happened, and who may be responsible for fueling it, are complicated questions, though reports suggest that several parties likely played contributing roles, including pharmaceutical manufacturers and distributors, doctors, health insurance companies, rogue pharmacies, and drug dealers and addicts. Many federal departments and agencies are involved in efforts to combat opioid abuse and addiction, including a law enforcement agency within the U.S. Department of Justice, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), which is the focus of this report. The primary federal law governing the manufacture, distribution, and use of prescription and illicit opioids is the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), a statute that the DEA is principally responsible for administering and enforcing. The CSA and DEA regulations promulgated thereunder establish a framework through which the federal government regulates the manufacture, distribution, importation, exportation, and use of certain substances which have the potential for abuse or psychological or physical dependence, including opioids. -

Review of the Drug Enforcement Administration's Regulatory And

Office of the Inspector General U.S. Department of Justice OVERSIGHT INTEGRITY GUIDANCE Review of the Drug Enforcement Administration’s Regulatory and Enforcement Efforts to Control the Diversion of Opioids Evaluation and Inspections Division 19-05 September 2019 (Revised) Executive Summary Review of the Drug Enforcement Administration’s Regulatory and Enforcement Efforts to Control the Diversion of Opioids Introduction Results in Brief In this review, the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) We found that DEA was slow to respond to the examined the regulatory activities and enforcement significant increase in the use and diversion of opioids efforts of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) since 2000. We also found that DEA did not use its from fiscal year (FY) 2010 through FY 2017 to combat available resources, including its data systems and the diversion of opioids to unauthorized users. strongest administrative enforcement tools, to detect According to the Centers for Disease Control and and regulate diversion effectively. Further, we found Prevention (CDC), as of 2017 in the United States more that DEA policies and regulations did not adequately than 130 people die every day from opioid overdose. hold registrants accountable or prevent the diversion of Since 2000, more than 300,000 Americans have lost pharmaceutical opioids. Lastly, we found that while the their lives to an opioid overdose. The misuse of and Department and DEA have recently taken steps to addiction to opioids, including prescription pain address the crisis, more work is needed. relievers, heroin, and synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, DEA Was Slow to Respond to the Dramatic Increase in has led to a national crisis that affects not only public Opioid Abuse and Needs to More Fully Utilize Its health, but also the social and economic welfare of the Regulatory Authorities and Enforcement Resources to country. -

Methods, Trends and Solutions for Drug Diversion by Tina Kristof

Methods, Trends and Solutions for Drug Diversion by Tina Kristof IAHSS-F RS-18-01 February 8, 2018 Evidence Based Healthcare Security Research Series IAHSS Foundation The International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety - Foundation (IAHSS Foundation) was established to foster and promote the welfare of the public through educational and research and development of healthcare security and safety body of knowledge. The IAHSS Foundation promotes and develops educational research into the maintenance and improvement of healthcare security and safety management as well as develops and conducts educational programs for the public. For more information, please visit: www.iahssf.org. The IAHSS Foundation creates value and positive impact on our profession and our industry…..and we are completely dependent on the charitable donations of individuals, corporations and organizations. Please realize the value of the Foundation’s research – and help us continue our mission and our support to the healthcare industry and the security and safety professionals that serve our institutions, staff and most importantly – our patients. To make a donation or to request assistance from the IAHSS Foundation, please contact Nancy Felesena at (888) 353-0990. Thank You for our continued support. Karim H. Vellani, CPP, CSC Committee Chair IAHSS Foundation IAHSS Foundation’s Evidence Based Healthcare Security Research Committee KARIM H. VELLANI, CPP, CSC BRYAN WARREN, MBA, CHPA, CPO-I Threat Analysis Group, LLC Carolinas HealthCare System RON HAWKINS THOMAS TAGGART Security Industry Association Paladin Security MAUREEN MCMAHON RN, BSN, MS STEPHEN A. TARANTO, Jr., J.D. Boston Medical Center Boston University Medical Center BONNIE MICHELMAN, CPP, CHPA KEN WHEATLEY, MA, CPP Massachusetts General Hospital/Partners Royal Security Group, LLC Healthcare P a g e | 1 Introduction Drug abuse in the United States has reached epidemic proportions. -

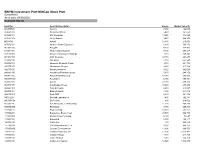

BNYM Investment Port:Midcap Stock Port (Unaudited) As of Date: 09/30/2020 Common Stocks

BNYM Investment Port:MidCap Stock Port (Unaudited) As of date: 09/30/2020 Common Stocks Identifier Security Description Shares Market Value ($) 002535300 Aaron's 7,450 422,043 00404A109 Acadia Healthcare 5,480 161,550 004498101 ACI Worldwide 13,250 346,223 00508Y102 Acuity Brands 9,470 969,255 BD845X2 Adient 12,480 216,278 00737L103 Adtalem Global Education 6,800 166,872 00766T100 AECOM 4,170 174,473 018581108 Alliance Data Systems 7,130 299,317 01973R101 Allison Transmission Holdings 7,110 249,845 00164V103 AMC Networks 10,710 264,644 023436108 Amedisys 2,760 652,547 025932104 American Financial Group 3,310 221,704 03073E105 AmerisourceBergen 2,220 215,162 042735100 Arrow Electronics 5,620 442,069 04280A100 Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals 5,670 244,150 045487105 Associated Banc-Corp 47,940 605,003 05329W102 Autonation 6,980 369,451 05368V106 Avient 23,030 609,374 053774105 Avis Budget Group 10,600 278,992 05464C101 Axon Enterprise 2,410 218,587 062540109 Bank of Hawaii 4,830 244,012 06417N103 Bank OZK 6,630 141,352 090572207 Bio-Rad Laboratories 1,480 762,881 09073M104 Bio-Techne 880 218,002 05550J101 BJs Wholesale Club Holdings 11,270 468,269 09227Q100 Blackbaud 3,750 209,363 103304101 Boyd Gaming 18,350 563,162 105368203 Brandywine Realty Trust 93,500 966,790 11120U105 Brixmor Property Group 6,300 73,647 117043109 Brunswick 8,150 480,117 12685J105 Cable One 300 565,629 127190304 CACI International, Cl. A 3,980 848,377 12769G100 Caesars Entertainment 11,890 666,553 133131102 Camden Property Trust 11,390 1,013,482 134429109 Campbell Soup 4,440 -

DRUG DIVERSION: ENFORCEMENT TRENDS, INVESTIGATION, & PREVENTION Regina F

DRUG DIVERSION: ENFORCEMENT TRENDS, INVESTIGATION, & PREVENTION Regina F. Gurvich, MBA, CHC, CHPC Agenda ◦ Definitions, causes, and sources ◦ Regulations and enforcement trends ◦ Role of the Compliance Officer ◦ Investigating and preventing drug diversion ◦ Case study 1 The estimated cost of controlled prescription drug diversion and abuse to Federal, State, and private medical insurers is approximately $72.65 billion a year. "The President’s FY 2018 Budget Request supports $27.8 billion for drug control efforts spanning prevention, treatment, interdiction, international operations, and law enforcement across 14 Executive Branch departments, the Federal Judiciary, and the District of Columbia. This represents an increase of $279.7 million (1.0 percent) over the annualized Continuing Resolution (CR) level in FY 2017 of $27.5 billion. Within this total, the Budget supports $1.3 billion in investments authorized by the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA) the 21st Century Cures Act, and other opioid-specific programs to help address the opioid epidemic." "National Drug Control Budget: FY 2018 Funding Highlights" (Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President, Office of National Drug Control Policy), May 2017, p. 2. National Drug Control Budget: FY 2018 Funding Highlights" (Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President, Office of National Drug Control Policy), May 2017, Table 1, p. 16; Table 2, p. 18; and Table 3, p. 19. 3 2 Definition Drug diversion is the illegal distribution or abuse of prescription drugs or their use for unintended or illicit purposes ◦ Often due to addiction or for financial gain ◦ Proliferation of pain clinics has led to an increase in the illegal distribution of expired or counterfeit medications ◦ High-value and Schedule II – V Controlled Substances frequently diverted: ◦ Opioids ◦ Performance enhancing drugs (e.g. -

GAO-01-1011 Attention Disorder Drugs: Few Incidents of Diversion

United States General Accounting Office GAO Report to Congressional Requesters September 2001 ATTENTION DISORDER DRUGS Few Incidents of Diversion or Abuse Identified by Schools GAO-01-1011 Contents Letter 1 Results in Brief 2 Background 2 Few Incidents of Diversion or Abuse of Attention Disorder Drugs Identified by Schools 6 Most Schools Dispense Attention Disorder Medications and Follow Drug Security Procedures 10 Many States and Local School Districts Have Provisions for School Administration of Medications 15 Conclusions 19 Agency Comments 20 Appendix I Objectives, Scope and Methodology 21 Appendix II Survey of Public School Principals – Diversion/Abuse of Medication for Attention Disorders 26 Appendix III State Controls on Dispensing of Drugs in Public Schools 33 Appendix IV Anecdotal Accounts of School-Based Diversion or Abuse of Attention Disorder Medications 36 Appendix V Studies Related to Diversion or Abuse of Methylphenidate by School-Aged Children 38 Appendix VI State Statutes, Regulations, and Mandatory Policies Addressing the Administration of Medication to Students 40 Page i GAO-01-1011 Attention Disorder Drugs Appendix VII GAO Contacts and Staff Acknowledgments 46 Tables Table 1:Rise in Production Quota for Methylphenidate and Amphetamine 5 Table 2:Measures Taken by School Officials as a Consequence of Diversion or Abuse of Attention Disorder Drugs 9 Table 3: School Personnel Dispensing Attention Disorder Medication 13 Table 4: Sample of Schools in Our Study 23 Figures Figure 1: Brand Name Methylphenidate Pills 4 Figure -

Generics Breakout Welcome

Generics Breakout Welcome David Picard Senior Vice President, Global Generic Pharmaceuticals Discussion Agenda • CERTIO Enhancements • American Health Packaging Alan Ratliff, Director, Supplier Trade o Kyle Pudenz, Senior Vice President, o Manufacturer and Data Services Relations • Generic Sourcing • Stable Supply Initiative o Chris Doerr, Vice President, Global o Heather Ryan, Senior Manager, Drug Shortage Generic Sourcing Solutions • Q&A SM • SureSupply o Heather Odenwelder, Senior Director, Category Management o Charles Hartenstine, Senior Director, Category Management CERTIO 2020 AmerisourceBergen Switzerland Kyle Pudenz Senior Vice President, Manufacturer and Data Services CERTIO® 2020 Evolving the CERTIO solution to address key business challenges. Further Supply Chain Integration Support Proactive Communication Easier to Use Project Overview Working with key stakeholders to address your business needs CERTIO 2020 Kickoff CERTIO Champions Sessions December 14 2019 Unique CERTIO Champions 108+ 9 Engaged CERTIO Users November Enhanced CERTIO 9 Dashboards 90+ CERTIO 2020 Launch CERTIO® 2020 and Beyond Continuing to shape your preferred supply chain solution • Launching November 9, 2020 o No change in current functionality Contact Upcoming training opportunities o [email protected] • Platform Evolution 2021 o Product Oversight o Failure to Supply o …and more! Special thanks to our CERTIO® Champions! Manufacturer Partners AmerisourceBergen Ajanta Lannett Global Generics Leadership Alembic Lupin Category Management Apotex Mallinckrodt -

ABCDEF LAST UPDATED: 05/28/2014 This Reflects the Last Date of Any Changes Made to the List

ABCDEF LAST UPDATED: 05/28/2014 This reflects the last date of any changes made to the list. Authorized Distributors Below is a list of Roxane Laboratories, Inc. (RLI) Authorized Distributors. These distributors have met RLI's requirements to distribute RLI's products. Authorized Distributors listed below are approved to distribute the entire RLI product line provided that they have the appropriate licenses. AmerisourceBergen Drug Corp AmerisourceBergen Drug Corp 172 Cahaba Valley Pkwy PELHAM AL AmerisourceBergen Drug Corp 1825 S 43rd Ave STE B PHOENIX AZ AmerisourceBergen Drug Corp 1851 California Ave CORONA CA AmerisourceBergen Drug Corp 1325 W Striker Ave SACRAMENTO CA AmerisourceBergen Drug Corp 24903 Avenue Kearny VALENCIA CA AmerisourceBergen Drug Corp 501 W 44th Ave DENVER CO AmerisourceBergen Drug Corp 2100 Directors Row ORLANDO FL AmerisourceBergen Drug Corp 1085 N Satellite Blvd SUWANEE GA AmerisourceBergen Drug Corp 238 Sand Island Access Rd #M1 HONOLULU HI AmerisourceBergen Drug Corp 1001 W TAYLOR RD ROMEOVILLE IL AmerisourceBergen Drug Corp 322 N 3RD St PADUCAH KY AmerisourceBergen Drug Corp 101 Norfolk St MANSFIELD MA AmerisourceBergen Drug Corp One Industrial Park Dr WILLIAMSTON MI AmerisourceBergen Drug Corp 6810 Shady Oak Rd EDEN PRAIRIE MN AmerisourceBergen Drug Corp 11200 N CONGRESS AVE KANSAS CITY MO AmerisourceBergen Drug Corp 8190 Lackland Rd SAINT LOUIS MO AmerisourceBergen Drug Corp 6300 St Louis St MERIDIAN MS AmerisourceBergen Drug Corp 8605 Ebenezer Church Rd RALEIGH NC AmerisourceBergen Drug Corp 100 Friars