Tudor Kitchen Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Friends of the National Libraries: a Short History

Friends of the National Libraries: A Short History Saving the nation’s written and By Max Egremont printed heritage This history first appeared in a special edition of The Book Collector in Summer 2011, FNL’s eightieth year. The Trustees of Friends of the National Libraries are grateful to the publisher of The Book Collector for permission to reissue the article in its present, slightly amended, form. A Short History 1 HRH The Prince of Wales. © Hugo Burnand. 2 Friends of the National Libraries Friends of the National he Friends of the National Libraries began as a response to an emergency. From the start, the Friends were fortunate in their leadership. Sir Frederic Libraries has helped save TOn March 21 1931, the Times published a letter signed by a group of the great Kenyon was one of British Museum’s great directors and principal librarians, the nation’s written and and the good, headed by the name of Lord D’Abernon, the chairman of the Royal a classical and biblical scholar who made his name as a papyrologist and widened the printed history since Commission on National Museums and Galleries. The message was that there was appeal of the museum by introducing guide lecturers and picture postcards; he also had a need for an organisation similar to the National Art Collections Fund (now called literary credentials as the editor of the works of Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. 1931. FNL awards grants the Art Fund) but devoted to rare books and manuscripts. The reason for this The Honorary Treasurer Lord Riddell, a former associate of Lloyd George, came to national, regional was that sales of rare books and manuscripts from Britain to institutions and to from the world of politics and the press. -

Annual Review 2016/17

Historic Royal Places – Spines Format A4 Portrait Spine Width 35mm Spine Height 297mm HRP Text 20pt (Tracked at +40) Palace Text 30pt (Tracked at -10) Icon 20mm Wide (0.5pt/0.25pt) Annual Review 2016/17 1 2 06 Welcome to another chapter in our story Contents 07 Our work is guided by four principles 08 Chairman’s Introduction 09 Chief Executive – a reflection 10 The Year of the Gardens 14 Guardianship 20 Showmanship 26 Discovery 32 Independence 38 Money matters 39 Visitor trends 40 Summarised financial statements 42 Trustees and Directors 44 Supporters 46 Acknowledgments Clockwise from top left: The White Tower, Tower of London; the West Front, Hampton Court Palace; the East Front, Kensington Palace; the South Front, Hillsborough Castle; Kew Palace; Banqueting House. 4 This year, the famous gardens of Hampton Court Palace took Guardianship: Welcome to centre stage. Already a huge attraction in their own right, this Our work is We exist for tomorrow, not just for yesterday. Our job is to give year the historic gardens burst into even more vibrant life. these palaces a future as valuable as their past. We know how another Prompted by the 300th anniversary of the birth of Lancelot guided by four precious they and their contents are, and we aim to conserve ‘Capability’ Brown, we created a spectacular programme of them to the standard they deserve: the best. chapter in exhibitions, events and activities. A highlight was the royal principles Discovery: opening of the Magic Garden; our playful and spectacular We explain the bigger picture, and then encourage people to our story 21st century contribution to 500 years of garden history. -

Jewel Tower – Final Interpretation Plan

Jewel Tower FINAL Interpretation Plan Curatorial Department 2012/13 Contents 1. Introduction 1.1 Site summary and context of the plan 1.2 Project team 2. History of the site 2.1 Summary 2.2 History of the building and important associations 2.3 Description and features 2.4 Points of significance 3. Conservation management 3.1 Designations 3.2 Condition survey 3.3 Conservation issues 3.4 Parameters for new interpretation 4. Collections 4.1 Summary of collections 4.2 Collections conservation 5. Audiences 5.1 Visitor numbers 5.2 Analysis 5.3 Education visits 5.4 Neighbouring attractions 5.5 Target audiences 6. Existing interpretation and visitor experience 6.1 Audit of current interpretation 6.2 Guidebook 6.3 Events 6.4 Website 7. Interpretation proposals 7.1 Themes 7.2 Interpretation approach 7.3 The scheme 7.4 Maintenance 8. Appendices i) Future work ii) Copy of visitor questionnaire and results iii) Collections in store iv) Activity sheet v) Education visits at the Houses of Parliament vi) Site plan 2 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Site summary and context of the plan The Jewel Tower is a three storey building lying opposite the Houses of Parliament in the heart of London. It was built around 1365 to house Edward III’s personal treasure as part of the palace at Westminster, and is one of the few buildings from this complex to survive today. In the 17th century, the Jewel Tower became the record office for the Houses of Lords and from 1869, it was the home of the Weights and Measures office, which set standards used across the British Empire. -

LONDON the DORCHESTER Two Day Itinerary: Old Favourites When It Comes to History, Culture and Architecture, Few Cities Can Compete with London

LONDON THE DORCHESTER Two day itinerary: Old Favourites When it comes to history, culture and architecture, few cities can compete with London. To look out across the Thames is to witness first-hand how effortlessly the city accommodates the modern while holding onto its past. Indeed, with an abundance of history to enjoy within its palaces and museums and stunning architecture to see across the city as a whole, exploring London with this one-day itinerary is an irresistible prospect for visitors and residents alike. Day One Start your day in London with a visit to Buckingham Palace, just 20 minutes’ walk from the hotel or 10 minutes by taxi. BUCKINGHAM PALACE T: 0303 123 7300 | London, SW1A 1AA Buckingham Palace is the 775-room official residence of the Royal Family. During the summer, visitors can take a tour of the State Rooms, the Royal Mews and the Queen’s Gallery, which displays the Royal Collection’s priceless artworks. Changing the Guard takes place every day at 11am in summer (every other day in winter) for those keen to witness some traditional British pageantry. Next, walk to Westminster Abbey, just 15 minutes away from the Palace. WESTMINSTER ABBEY T: 020 7222 5152 | 20 Dean’s Yard, London, SW1P 3PA With over 1,000 years of history, Westminster Abbey is another London icon. Inside its ancient stone walls, 17 monarchs have been laid to rest over the course of the centuries. Beyond its architectural and historical significance, the Abbey continues to be the site in which new monarchs are crowned, making it an integral part of London’s colourful biography. -

The British Museum Annual Reports and Accounts 2019

The British Museum REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2020 HC 432 The British Museum REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2020 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 9(8) of the Museums and Galleries Act 1992 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed on 19 November 2020 HC 432 The British Museum Report and Accounts 2019-20 © The British Museum copyright 2020 The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as British Museum copyright and the document title specifed. Where third party material has been identifed, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries related to this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/ofcial-documents. ISBN 978-1-5286-2095-6 CCS0320321972 11/20 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fbre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Ofce The British Museum Report and Accounts 2019-20 Contents Trustees’ and Accounting Ofcer’s Annual Report 3 Chairman’s Foreword 3 Structure, governance and management 4 Constitution and operating environment 4 Subsidiaries 4 Friends’ organisations 4 Strategic direction and performance against objectives 4 Collections and research 4 Audiences and Engagement 5 Investing -

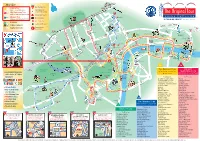

A4 Web Map 26-1-12:Layout 1

King’s Cross Start St Pancras MAP KEY Eurostar Main Starting Point Euston Original Tour 1 St Pancras T1 English commentary/live guides Interchange Point City Sightseeing Tour (colour denotes route) Start T2 W o Language commentaries plus Kids Club REGENT’S PARK Euston Rd b 3 u Underground Station r n P Madame Tussauds l Museum Tour Russell Sq TM T4 Main Line Station Gower St Language commentaries plus Kids Club q l S “A TOUR DE FORCE!” The Times, London To t el ★ River Cruise Piers ss Gt Portland St tenham Ct Rd Ru Baker St T3 Loop Line Gt Portland St B S s e o Liverpool St Location of Attraction Marylebone Rd P re M d u ark C o fo t Telecom n r h Stansted Station Connector t d a T5 Portla a m Museum Tower g P Express u l p of London e to S Aldgate East Original London t n e nd Pl t Capital Connector R London Wall ga T6 t o Holborn s Visitor Centre S w p i o Aldgate Marylebone High St British h Ho t l is und S Museum el Bank of sdi igh s B tch H Gloucester Pl s England te Baker St u ga Marylebone Broadcasting House R St Holborn ld d t ford A R a Ox e re New K n i Royal Courts St Paul’s Cathedral n o G g of Justice b Mansion House Swiss RE Tower s e w l Tottenham (The Gherkin) y a Court Rd M r y a Lud gat i St St e H n M d t ill r e o xfo Fle Fenchurch St Monument r ld O i C e O C an n s Jam h on St Tower Hill t h Blackfriars S a r d es St i e Oxford Circus n Aldwyc Temple l a s Edgware Rd Tower Hil g r n Reg Paddington P d ve s St The Monument me G A ha per T y Covent Garden Start x St ent Up r e d t r Hamleys u C en s fo N km Norfolk -

Aldwych-House-Brochure.Pdf

Executive summary • An iconic flagship in the heart of Midtown • This imposing building invested with period grandeur, has been brought to life in an exciting and modern manner • A powerful and dramatic entrance hall with 9 storey atrium creates a backdrop to this efficient and modern office • A total of 142,696 sq ft of new lettings have taken place leaving just 31,164 sq ft available • A space to dwell… 4,209 – 31,164 SQ FT 4 | ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM | 5 Aldwych House • MoreySmith designed reception • Full height (9 storey) central atrium fusing a modern which provides a light, modern, interior with imposing spacious circulation area 1920s architecture • Floors are served by a newly refurbished lightwell on the west side and a dramatically lit internal Aldwych House totals 174,000 atrium to the east from lower sq ft over lower ground to 8th ground to 3rd floor floors with a 65m frontage • An extensive timber roof terrace onto historic Aldwych around a glazed roof area • Showers, cycle storage and a drying room are located in the basement with easy access from the rear of the building • The ROKA restaurant is on the ground floor 6 | ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM | 7 8 | ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM Floorplate Typical upper floor c. 18,000 sq ft Typical upper floor CGI with sample fit-out 10 | ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM | 11 Floorplate Typical upper floor with suite fit-out 12 | ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM | 13 SOHO TOTTENHAM COURT ROAD MIDTOWN | LONDON Aldwych House, now transformed as part of the dynamic re-generation of this vibrant eclectic midtown destination, stands tall and COVENT GARDEN commanding on the north of the double crescent of Aldwych. -

Restoration and Renewal of the Palace of Westminster

Availaible online at www.parliament.uk/jcpow © Parliamentary Copyright House of Lords and House of Commons 2016 OF WESTMINSTER: SESSION 2016–17: FROM THE JOINT COMMITTEE ON PALACE FIRST REPORT This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament Licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright House of Lords House of Commons Joint Committee on the Palace of Westminster Restoration and Renewal of the Palace of Westminster First Report of Session 2016–17 HL Paper 41 HC 659 HL Paper 41 HC 659 House of Lords House of Commons Joint Committee on the Palace of Westminster Restoration and Renewal of the Palace of Westminster First Report of Session 2016–17 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Lords to be printed on 5 September 2016 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 5 September 2016 HL Paper 41 HC 659 Published on 8 September 2016 by authority of the House of Lords and House of Commons Joint Committee on the Palace of Westminster The Joint Committee on the Palace of Westminster was appointed in July 2015 to consider the restoration and renewal of the Palace of Westminster. The House of Commons Members were appointed on 16 July 2015. The House of Lords Members were appointed on 20 July 2015 and reappointed on 25 May 2016. Membership HOUSE OF LORDS HOUSE OF COMMONS Baroness Stowell of Beeston (Conservative) Chris Grayling MP (Conservative) (Co-Chairman) (Co-Chairman) Lord Carter of Coles (Labour) Chris Bryant MP (Labour) Lord Deighton (Conservative) -

Anecdotes of Painting in England : with Some Account of the Principal

C ' 1 2. J? Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/paintingineng02walp ^-©HINTESS <0>F AEHJKTID 'oat/ /y ' L o :j : ANECDOTES OF PAINTING IN ENGLAND; WITH SOME ACCOUNT OF THE PRINCIPAL ARTISTS; AND INCIDENTAL NOTES ON OTHER ARTS; COLLECTED BY THE LATE MR. GEORGE VERTUE; DIGESTED AND PUBLISHED FROM HIS ORIGINAL MSS. BY THE HONOURABLE HORACE WALPOLE; WITH CONSIDERABLE ADDITIONS BY THE REV. JAMES DALLAWAY. LONDON PRINTED AT THE SHAKSPEARE PRESS, BY W. NICOL, FOR JOHN MAJOR, FLEET-STREET. MDCCCXXVI. LIST OF PLATES TO VOL. II. The Countess of Arundel, from the Original Painting at Worksop Manor, facing the title page. Paul Vansomer, . to face page 5 Cornelius Jansen, . .9 Daniel Mytens, . .15 Peter Oliver, . 25 The Earl of Arundel, . .144 Sir Peter Paul Rubens, . 161 Abraham Diepenbeck, . 1S7 Sir Anthony Vandyck, . 188 Cornelius Polenburg, . 238 John Torrentius, . .241 George Jameson, his Wife and Son, . 243 William Dobson, . 251 Gerard Honthorst, . 258 Nicholas Laniere, . 270 John Petitot, . 301 Inigo Jones, .... 330 ENGRAVINGS ON WOOD. Arms of Rubens, Vandyck & Jones to follow the title. Henry Gyles and John Rowell, . 39 Nicholas Stone, Senior and Junior, . 55 Henry Stone, .... 65 View of Wollaton, Nottinghamshire, . 91 Abraham Vanderdort, . 101 Sir B. Gerbier, . .114 George Geldorp, . 233 Henry Steenwyck, . 240 John Van Belcamp, . 265 Horatio Gentileschi, . 267 Francis Wouters, . 273 ENGRAVINGS ON WOOD continued. Adrian Hanneman, . 279 Sir Toby Matthews, . , .286 Francis Cleyn, . 291 Edward Pierce, Father and Son, . 314 Hubert Le Soeur, . 316 View of Whitehall, . .361 General Lambert, R. Walker and E. Mascall, 368 CONTENTS OF THE SECOND VOLUME. -

3-Day London City Guide a Preplanned Step-By-Step Time Line and City Guide for London

3 days 3-day London City Guide A preplanned step-by-step time line and city guide for London. Follow it and get the best of the city. 3-day London City Guide 2 © PromptGuides.com 3-day London City Guide Overview of Day 1 LEAVE HOTEL Tested and recommended hotels in London > Take subway or bus to Westminster station 09:00-09:10 Big Ben One of London's Page 5 best-known landmarks 09:10-09:20 Houses of Parliament One of London's most Page 5 impressive building 09:20-09:30 Westminster Bridge Excellent spot for taking Page 5 photos of Big Ben and Take a walk to Nr. 10 Downing street - 5’ Houses of Parliament 09:35-09:45 Nr.10 Downing Street Official home and office Page 6 of Britain's Prime Take a walk to Westminster Abbey - 5’ Minister 09:50-11:20 Westminster Abbey One of the finest Page 6 examples of medieval Take Bus line 148 from Parliament Square/Westminster architecture in Europe Abbey stop to Hyde Park Corner stop (Direction: White City Bus Station) Take a walk to Buckingam Palace - 10’ in all 11:30-12:00 Buckingham Palace One of London's best Page 7 recognized landmarks Take a walk to St. James's Park - 5’ 12:05-12:35 St. James's Park Lovely park with a duck Page 7 and pelican pond Lunch time Take a walk to Cabinet War Room 13:45-15:15 Cabinet War Rooms Unique historical place Page 7 Take a walk to Charing Cross station Take Northern Line to Tottenham Court Road station (Direction: Edgeware or High Barnet) Take a walk to British Museum - 25’ in all 15:40-17:30 The British Museum Oldest museum in the Page 8 world Take a walk to Holborn -

The Old War Office Building

MINISTRY OF DEFENCE The Old War Office Building A history The Old War Office Building …a building full of history Foreword by the Rt. Hon Geoff Hoon MP, Secretary of State for Defence The Old War Office Building has been a Whitehall landmark for nearly a century. No-one can fail to be impressed by its imposing Edwardian Baroque exterior and splendidly restored rooms and stairways. With the long-overdue modernisation of the MOD Main Building, Defence Ministers and other members of the Defence Council – the Department’s senior committee – have moved temporarily to the Old War Office. To mark the occasion I have asked for this short booklet, describing the history of the Old War Office Building, to be published. The booklet also includes a brief history of the site on which the building now stands, and of other historic MOD headquarters buildings in Central London. People know about the work that our Armed Forces do around the world as a force for good. Less well known is the work that we do to preserve our heritage and to look after the historic buildings that we occupy. I hope that this publication will help to raise awareness of that. The Old War Office Building has had a fascinating past, as you will see. People working within its walls played a key role in two World Wars and in the Cold War that followed. The building is full of history. Lawrence of Arabia once worked here. I am now occupying the office which Churchill, Lloyd-George and Profumo once had. -

Collecting the World

Large print text Collecting the World Please do not remove from this display Collecting the World Founded in 1753, the British Museum opened its doors to visitors in 1759. The Museum tells the story of human cultural achievement through a collection of collections. This room celebrates some of the collectors who, in different ways, have shaped the Museum over four centuries, along with individuals and organisations who continue to shape its future. The adjoining galleries also explore aspects of collecting. Room 1: Enlightenment tells the story of how, in the early Museum, objects and knowledge were gathered and classified. Room 2a: The Waddesdon Bequest, displays the collection of Renaissance and Baroque masterpieces left to the British Museum by Baron Ferdinand Rothschild MP at his death in 1898. Gallery plan 2 Expanding Horizons Room 1 Enlightenment Bequest Waddesdon The Room 2a 1 3 The Age Changing of Curiosity Continuity 4 Today and Tomorrow Grenville shop 4 Collecting the World page Section 1 6 The Age of Curiosity, 18th century Section 2 2 5 Expanding Horizons, 19th century Section 3 80 Changing Continuity, 20th century Section 4 110 Today and Tomorrow, 21st century Portraits at balcony level 156 5 Section 1 The Age of Curiosity, 18th century Gallery plan 2 Expanding Horizons 1 3 The Age Changing of Curiosity Continuity 4 Today and Tomorrow 6 18th century The Age of Curiosity The Age of Curiosity The British Museum was founded in 1753 as a place of recreation ‘for all studious and curious persons’. Its founding collection belonged to the physician Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753).