October-2019-Issue-No.-4-Art.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

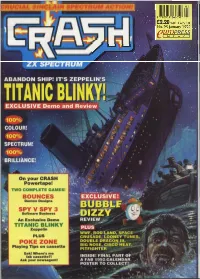

Crash Magazine

CRUCIAL SINCLAIR SPECTRUM ACTION! A— ZX SPECTRUM ABANDON SHIP! IT'S ZEPPELIN'S EXCLUSIVE Demo and Review * •w 100% • f « COLOUR! 'IP 100% A J? * SPECTRUM! * #v b Jfr * 100% • JUP BRILLIANCE1. • v kJ* V in . N > On your CRASH k / H if * - • V Powertape! -T^* 1 J ^ I A TWO COMPLETE GAMES! p, % -- ' • I iVik (T* BOUNCES EXCLUSIVE! ^ Denton Designs niln P SPY V SPY 3 SB Software Business REVIEW^. a. • . > W An Exclusive Demo — \ / f ' TITANIC BLINKY PLUS Jf Zeppelin WWF, ROD-LAND, SPACE fa' V ' PLUS CRUSADE, LOONEY TUNES, // DOUBLE DRAGON III, / t • N POKE ZONE % Playing Tips on cassette BIG NOSE, CISCO HEAT, ^ ' V , ?}/ i/Tr j PITFIGHTER Tjf /1 / ' Eek! Where's me ' j- A>\r I'll J f i''' % fab cassette?! INSIDE! FINAL PART OF * / ^ Ask your newsagent! A FAB 1992 CALENDAR M * / I POSTER TO COLLECT**,, * . a V / Y ' . y ' X- f 'V* ~ ^ - ^LiOGMe^T LiiVd 'a j cAPacowiidl All MGHI j fit ,l $ All filGHIS Pf'Jjr/f OCEAN SOFTWARE LIMITED • 6 CENTRA' TELEPHONE; 061 832 6*33 3 o MA1+ tt I ° < m i i n FS ^^^CifTnj r'lT/ili^ > ® K 1 • j • ^^ (SrrrD>3 ^^ / i\i i \ v.. o. 1 _ - -lift . • /V Vi .vr f«tl . -J I'l 'IKMni'rlirllNil Here you go, all — the second part of our fantastlco double sided poster-calendar, brought to you courtesy of the wonderfully mega-brill talents of Oliver Frey (autographs by appointment only). Unless you're a complete drongo, you'll have saved the other half of the poster from last month's Issue. -

Writing in Grey Joseph Schwartze UCCS Honors Program

Writing in Grey Joseph Schwartze UCCS Honors Program A Darker World The stories in this section look at the darker parts of our world. Fantasy is unnecessary to see depictions of true evil; it exists in day to day life. The mind does not have to warp itself in perverted defense mechanisms to see darkness in our average lives. These stories examine the consequences of the bad events in our world, from the lasting effects on a single person to the terrible choices some people are forced to make. We do not always know the darkness that surrounds us; only an unremarkable symbol might be the reminder. Other times, the darkness around us can be from our own choices, our own accomplishments, and we must live with that stink forever. These stories explore the grey in our world and how the black and white can mix into unfortunate realities. Choices in the Dark Clarissa took the shot, and she savored the burning sensation in her throat. She needed it, the pain. She needed the numbness that followed even more. Her eyes closed, and when she opened them, some 20-something college boy sat next to her. He was dressed like a preppy frat boy, with his khakis and a light blue polo shirt. She knew the drill. A pretty smile painted her features, and she leaned against the counter while she waited for him to say something. A quick adjustment and her dark red, revealing dress showed off more of her thighs and cleavage. “Can I buy you a drink?” he asked confidently. -

Status Quo Just Supposin'... Mp3, Flac, Wma

Status Quo Just Supposin'... mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Just Supposin'... Country: Netherlands Released: 1980 Style: Pop Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1376 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1399 mb WMA version RAR size: 1542 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 265 Other Formats: DXD ASF MIDI DXD WAV ASF AC3 Tracklist Hide Credits What You're Proposing A1 4:16 Written-By – Frost*, Rossi* Run To Mummy A2 3:09 Written-By – Bown*, Rossi* Don't Drive My Car A3 4:36 Written-By – Bown*, Parfitt* Lies A4 4:01 Written-By – Frost*, Rossi* Over The Edge A5 4:29 Written-By – Lancaster*, Lamb* The Wild Ones B1 4:00 Written-By – Lancaster* Name Of The Game B2 4:31 Written-By – Lancaster*, Bown*, Rossi* Coming And Going B3 6:29 Written-By – Young*, Parfitt* Rock 'N' Roll B4 5:23 Written-By – Young*, Rossi* Credits Co-producer – John Eden, Status Quo Other [Editor In Chief] – Slavko Terzić Other [Reviewer] – Svetolik Jakovljević Notes Edition with red labels on black plastic cassette. Barcode and Other Identifiers Rights Society: SOKOJ Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Just Supposin'... (LP, 6302 057 Status Quo Vertigo 6302 057 UK 1980 Album) Just Supposin'... (LP, 6302 057 Status Quo Vertigo 6302 057 Germany 1980 Album) Just Supposin'... (LP, 6302 057 Status Quo PGP RTB 6302 057 Italy 1980 Album) 63 02 057, Just Supposin'... (LP, Vertigo, 63 02 057, Status Quo Spain 1981 58784 Album, S/Edition) Vertigo 58784 Just Supposin'... (LP, 6302 057 Status Quo Vertigo 6302 057 Netherlands 1980 Album) Related Music albums to Just Supposin'.. -

Status Quo – En Studie Av Ett Rockbands Karriär

“Together We Can Rock´n´Roll” Status Quo – en studie av ett rockbands karriär Eva Kjellander Pedagogiska institutionen/ Avd. för bild, musik och kulturpedagogik Växjö universitet Handledare: Boel Lindberg D-uppsats i Musikvetenskap Ht 2005 2 Abstract Eva Kjellander: “Together we can rock´n´roll”, Status Quo – a study of the career of a rock band. Växjö: Musicology 2005. 80p. The main purpose of this essay is on one hand to try to find and explain the formula of success of the rock group Status Quo, and on the other to elucidate and explain the foundation and essence in the music made by Status Quo, but also to study how, if and why the foundation and essence have changed over the years. The method of investigation is partly based on a musical analysis of three albums from three different periods: Hello! (1973), Ain´t Complaining (1988) and Heavy Traffic (2002), and partly on a sociological study of the group’s career between 1962 and today, 2005. The first part of the essay concerns the period between 1962-1973 with an analysis of the album Hello!; the second part concerns the period 1974-1988 and the album Ain´t Complaining; finally, the third part concerns the years between 1989-2002 with an intensified analysis of the album Heavy Traffic. In the forth part of the essay I discuss the career of Status Quo from a sociological point of view. I run to the conclusion that the essence of Status Quo is the boogie-woogie comp on Fender guitar by Rick Parfitt, the riff on Francis Rossis´ Fender guitar in combination with the base, the piano and the drums. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Előadó Album Címe a Balladeer Panama -Jewelcase- a Balladeer Where Are You, Bambi

Előadó Album címe A Balladeer Panama -Jewelcase- A Balladeer Where Are You, Bambi.. A Fine Frenzy Bomb In a Birdcage A Flock of Seagulls Best of -12tr- A Flock of Seagulls Playlist-Very Best of A Silent Express Now! A Tribe Called Quest Collections A Tribe Called Quest Love Movement A Tribe Called Quest Low End Theory A Tribe Called Quest Midnight Marauders A Tribe Called Quest People's Instinctive Trav Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothin' But a N Ab/Cd Cut the Crap! Ab/Cd Rock'n'roll Devil Abba Arrival + 2 Abba Classic:Masters.. Abba Icon Abba Name of the Game Abba Waterloo + 3 Abba.=Tribute= Greatest Hits Go Classic Abba-Esque Die Grosse Abba-Party Abc Classic:Masters.. Abc How To Be a Zillionaire+8 Abc Look of Love -Very Best Abyssinians Arise Accept Balls To the Wall + 2 Accept Eat the Heat =Remastered= Accept Metal Heart + 2 Accept Russian Roulette =Remaste Accept Staying a Life -19tr- Acda & De Munnik Acda & De Munnik Acda & De Munnik Adem-Het Beste Van Acda & De Munnik Live Met Het Metropole or Acda & De Munnik Naar Huis Acda & De Munnik Nachtmuziek Ace of Base Collection Ace of Base Singles of the 90's Adam & the Ants Dirk Wears White Sox =Rem Adam F Kaos -14tr- Adams, Johnny Great Johnny Adams Jazz.. Adams, Oleta Circle of One Adams, Ryan Cardinology Adams, Ryan Demolition -13tr- Adams, Ryan Easy Tiger Adams, Ryan Love is Hell Adams, Ryan Rock'n Roll Adderley & Jackson Things Are Getting Better Adderley, Cannonball Cannonball's Bossa Nova Adderley, Cannonball Inside Straight Adderley, Cannonball Know What I Mean Adderley, Cannonball Mercy -

теð¹ñ‚ÑšñКñƒð¾ Ðлбуð¼ ÑпиÑ

Ð¡Ñ‚ÐµÐ¹Ñ‚ÑŠÑ ÐšÑƒÐ¾ ÐÐ »Ð±ÑƒÐ¼ ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (Ð ´Ð¸ÑÐ ºÐ¾Ð³Ñ€Ð°Ñ„иÑÑ ‚а & график) Quid Pro Quo https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/quid-pro-quo-3487249/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/aquostic-%28stripped-bare%29- Aquostic (Stripped Bare) 17986778/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/famous-in-the-last-century- Famous in the Last Century 1134642/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-party-ain%27t-over-yet- The Party Ain't Over Yet 1134632/songs Bula Quo! https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/bula-quo%21-12015662/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/accept-no-substitute%21---the-definitive- Accept No Substitute! - The Definitive Hits hits-28668024/songs The Best of Status Quo https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-best-of-status-quo-384171/songs Gold https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/gold-3109981/songs In My Chair https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/in-my-chair-3797138/songs Down the Dustpipe https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/down-the-dustpipe-3714786/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/accept-no-substitute%21-the-definitive- Accept No Substitute! The Definitive Hits hits-48804332/songs Hit Album https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/hit-album-3785911/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/golden-hour-of-status-quo- Golden Hour of Status Quo 3772976/songs Fresh Quota https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/fresh-quota-3753088/songs The Party Aint Over Yet.. -

Mcdougall, Christopher

2 To John and Jean McDougall , my parents , who gave me everything and keep on giving 3 CHAPTER 1 To live with ghosts requires solitude. —ANNE M ICHAELS , Fugitive Pieces FOR DAYS, I’d been searching Mexico’s Sierra Madre for the phantom known as Caballo Blanco—the White Horse. I’d finally arrived at the end of the trail, in the last place I expected to find him—not deep in the wilderness he was said to haunt, but in the dim lobby of an old hotel on the edge of a dusty desert town.! “Sí, El Caballo está ,” the desk clerk said, nodding. Yes, the Horse is here. “For real?” After hearing that I’d just missed him so many times, in so many bizarre locations, I’d begun to suspect that Caballo Blanco was nothing more than a fairy tale, a local Loch Ness mons-truo dreamed up to spook the kids and fool gullible gringos. “He’s always back by five,” the clerk added. “It’s like a ritual.” I didn’t know whether to hug her in relief or high-five her in triumph. I checked my watch. That meant I’d actually lay eyes on the ghost in less than … hang on. “But it’s already after six.” The clerk shrugged. “Maybe he’s gone away.” I sagged into an ancient sofa. I was filthy, famished, and defeated. I was exhausted, and so were my leads. Some said Caballo Blanco was a fugitive; others heard he was a boxer who’d run off to punish himself after beating a man to death in the ring. -

Claire Gradidge, Thesis

UNIVERSITY OF WINCHESTER Innovating from Tradition: Creating an Historical Detective Novel for a Contemporary Audience. Claire Gradidge ORCID Number: 0000-0003-3978-8707 Doctor of Philosophy December 2017 This Thesis has been completed as a requirement for a postgraduate research degree of the University of Winchester. This page is intentionally left blank. DECLARATION AND COPYRIGHT STATEMENT Declaration: No portion of the work referred to in the Thesis has been submitted in support of an application for another degree or qualification of this or any other university or other institute of learning. I confirm that this Thesis is entirely my own work. Copyright: Copyright © Claire Gradidge 2017, ‘Innovating from Tradition: Creating an Historical Detective Novel for a Contemporary Audience’, University of Winchester, PhD Thesis pp 1- 335 ORCID Number: 0000-0003-3978-8707. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Copies (by any process) either in full, or of extracts, may be made only in accordance with instructions given by the author. Details may be obtained from the RKE centre, University of Winchester. This page must form part of any such copies made. Further copies (by any process) of copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the permission (in writing) of the author. No profit may be made from selling, copying or licensing the author’s work without further agreement. 1 Acknowledgements I should like to thank a number of people for their help and support during the course of my PhD studies. -

The Silence of the Lambs

THE SILENCE OF THE LAMB Thomas Harris CHAPTER 1 Behavioral Science, the FBI section that deals with serial murder, is on the bottom floor of the Academy building at Quantico, half-buried in the earth. Clarice Starling reached it flushed after a fast walk from Hogan's Alley on the firing range. She had grass in her hair and grass stains on her FBI Academy windbreaker from diving to the ground under fire in an arrest problem on the range. No one was in the outer office, so she fluffed briefly by her reflection in the glass doors. She knew she could look all right without primping. Her hands smelled of gunsmoke, but there was no time to wash--- Section Chief Crawford's summons had said now. She found Jack Crawford alone in the cluttered suite of offices. He was standing at someone else's desk talking on the telephone and she had a chance to look him over for the first time in a year. What she saw disturbed her. Normally, Crawford looked like a fit, middle-aged engineer who might have paid his way through college playing baseball--- a crafty catcher, tough when he blocked the plate. Now he was thin, his shirt collar was too big, and he had dark puffs under his reddened eyes. Everyone who could read the papers knew Behavioral Science section was catching hell. Starling hoped Crawford wasn't on the juice. That seemed most unlikely here. Crawford ended his telephone conversation with a sharp "No." He took her file from under his arm and opened it. -

Clarion West Presents Karen Lord

Clarion West presents Karen Lord [00:00:05] Welcome to The Seattle Public Library’s podcasts of author readings and library events. Library podcasts are brought to you by The Seattle Public Library and Foundation. To learn more about our programs and podcasts, visit our web site at w w w dot SPL dot org. To learn how you can help the library foundation support The Seattle Public Library go to foundation dot SPL dot org [00:00:36] Good evening. My name is Misha Stone I'm a Reader Services librarian here at The Seattle Public Library. Thank you for coming tonight. Thank you for joining us. I always love the Clarion West summer reader series both because I'm on the board now but you'll hear more about the board in a moment. But also just because I love meeting all of the authors who are here as instructors for the six week residential program it is lovely to have Karen Lord here tonight and as well as the 18 students here who are writing away. So thank you. Before I turn the program over to Klarion West a few items of business. This event is supported by the Seattle Public Library Foundation author series sponsor Gary Kunis and media sponsor the Seattle Times and presented in partnership with the university bookstore. Thank you Dwayne and Lily by books. And now I am turning the podium over to Mnisi sholl I [00:01:47] Mnisi shawl also known as Denise Tangela shawl. [00:01:51] Clarine West board member and lake I have this speech here that you guys all know so I'm not going to ask you to sing along but I'm tempted. -

No Truck with the Chilean Junta! Trade Union Internationalism, Australia and Britain,1973-1980

No Truck with the Chilean Junta! Trade Union Internationalism, Australia and Britain,1973-1980 No Truck with the Chilean Junta! Trade Union Internationalism, Australia and Britain,1973-1980 Ann Jones Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Jones, Ann, author. Title: No truck with the Chilean junta! : trade union internationalism, Australia and Britain, 1973-1980 / Ann Jones. ISBN: 9781925021530 (paperback) 9781925021547 (ebook) Subjects: International labor activities--History Labor movement--History. Labor unions--Australia. Labor unions--Great Britain. Labor unions--Chile--Political activity. Dewey Number 322.2 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Nic Welbourn and layout by ANU Press Cover image © Steve Bell 1987 - All Rights Reserved. http://www.belltoons.co.uk/reuse. Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgments . vii List of abbreviations . ix Introduction . 1 Britain 1 . The ‘principal priority’ of the campaign: The trade union movement . 25 2 . A ‘roll call’ of the labour movement: Harnessing labour participation . 63 3 . ‘Unique solidarity’? The mineworkers’ delegation, 1977 . 89 4 . Pinochet’s jets and Rolls Royce East Kilbride . 117 Australia 5 . Opening doors for Chile: Strategic individuals and networks . 155 6 . ‘Chile is not alone’: Actions for resource-sensible organisations .