David Mccullough, Whose Latest Book Is Titled "The Greater Journey, Americans in Paris"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Get a Taste of Summer at the South Berwick Strawberry Festival

HOT TUNES: York WHERE TO FIND LIVE MUSIC IndepeA publicationnd of SEACOASTen HIPPO t JUNE 23 - 29, 2011 www.yorkindependent.net FREE Get a taste of summer at the South Berwick Strawberry Festival INSIDE: WHERE TO SEE THE WHALES 5 Strawberry season One of the sweetest parts of summer is strawberry season and all the delicious shortcake that comes with it. In our second issue of this 13-week summer series of the York Independent, we look at the Strawberry Festival in South Berwick. Look for a new York Independent each Thurs- day through Sept. 8. If you have an event you want to tell us about, send the information to All Time Low all ages ...........mon AUG 1 comedian [email protected]. AZIZ ANSARI Stone Temple Pilots ........ tue AUG 2 Sunday, June 26 Also on the cover: Looking for hot tunes? Check out our listings on page 20. And hit the seas THURSDAY JUNE 30 Stone Temple Pilots .......wed AUG 3 for a little whale watching on page 8. Louis C.K. comedian, 2 shows .thu AUG 4 comedian JOHNPINETTE Queensryche .............................fri AUG 5 sunday july 3 York Independent Inside SAT 7/2•ALL AGES America ...................................sat AUG 6 Staff ThisWeek Reggae Revival with Ali EDitorial 4 THIS WEEK saturday Executive Editor Five things happening this week plus more ideas for Bob JULY 9 Campbell’s UB40, Junior Amy Diaz, [email protected], ext. 29 Contributing Editor fun any time. FRIDAY Marvin’s Wailers and Lisa Parsons, [email protected] JULY 8 SAGET ...............................sun Staff Writers Maxi Priest AUG 7 Racheal Akers, [email protected], ext. -

Full List of Book Discussion Kits – September 2016

Full List of Book Discussion Kits – September 2016 1776 by David McCullough -(Large Print) Esteemed historian David McCullough details the 12 months of 1776 and shows how outnumbered and supposedly inferior men managed to fight off the world's greatest army. Abraham: A Journey to the Heart of Three Faiths by Bruce Feiler - In this timely and uplifting journey, the bestselling author of Walking the Bible searches for the man at the heart of the world's three monotheistic religions -- and today's deadliest conflicts. Abundance: a novel of Marie Antoinette by Sena Jeter Naslund - Marie Antoinette lived a brief--but astounding--life. She rebelled against the formality and rigid protocol of the court; an outsider who became the target of a revolution that ultimately decided her fate. After This by Alice McDermott - This novel of a middle-class American family, in the middle decades of the twentieth century, captures the social, political, and spiritual upheavals of their changing world. Ahab's Wife, or the Star-Gazer by Sena Jeter Naslund - Inspired by a brief passage in Melville's Moby-Dick, this tale of 19th century America explores the strong-willed woman who loved Captain Ahab. Aindreas the Messenger: Louisville, Ky, 1855 by Gerald McDaniel - Aindreas is a young Irish-Catholic boy living in gaudy, grubby Louisville in 1855, a city where being Irish, Catholic, German or black usually means trouble. The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho - A fable about undauntingly following one's dreams, listening to one's heart, and reading life's omens features dialogue between a boy and an unnamed being. -

David Mccullough to Headline Special Talk at the History Center

Media Contacts: Ned Schano Brady Smith 412-454-6382 412-454-6459 [email protected] [email protected] David McCullough to Headline Special Talk at the History Center Focusing on the Steamboat Arabia -The two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning author will join History Center President and CEO Andy Masich and Steamboat Arabia excavator Dave Hawley for an engaging discussion- PITTSBURGH, Nov. 24, 2014 – The Senator John Heinz History Center will welcome America’s favorite historian and Pittsburgh native David McCullough for a special panel discussion on the importance of America’s river cities with History Center President and CEO Andy Masich and Arabia Steamboat Museum Director Dave Hawley on Tuesday, Dec. 2, at 11 a.m. Held in in conjunction with the museum’s newest exhibition, Pittsburgh’s Lost Steamboat: Treasures of the Arabia , the three historians will discuss Pittsburgh as the “Gateway to the West,” the region’s booming steamboat-building industry during the 19 th century, and the significance of the Arabia’s vast archaeological treasures. The Treasures of the Arabia exhibit features nearly 2,000 objects from the Steamboat Arabia’s massive cargo. In 1856, the Pittsburgh-built vessel carrying more than one million objects hit a snag and sank in the Missouri River. More than 130 years later, a group of modern day treasure hunters rediscovered the Arabia buried 45 feet below a cornfield a half-mile from the river. Remarkably, the anaerobic (oxygen- free) environment perfectly preserved most of the boat’s cargo in excellent condition, including fine dishware, clothing, and even bottled food such as pickles and ketchup. -

David Mccullough

A teacher’s guide to DAVID C ULLOUGH M C WINNER OF THE PULITZER PRIZE TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 About the Author 1 Resources 1 Key Figures 2 Pre-Reading Knowledge 5 Part I, Chapter 1 6 Part I, Chapter 2 8 Part I, Chapter 3 11 Part II, Chapter 4 14 Part II, Chapter 5 17 Part III, Chapter 6 19 Part III, Chapter 7 22 INTRODUCTION Although the passage of the Declaration of Independence is a universally taught event in the United States, most high school students’ knowledge tends to be confined to the events that occurred in the city of Philadelphia during the month of July. In focusing on the events throughout the year of 1776, Pulitzer Prize–winning historian David McCullough gives students a deep understanding, from both sides of the conflict, of the events, people, and decisions that led to the creation of the United States. McCullough’s extensively researched work is filled with primary sources, reinforcing details and differing points of view on the events presented within the text, all of which makes 1776 an excellent text for use with the Common Core standards. This teacher’s guide provides a brief summary of 1776, divided by chapter and then subdivided by section. Each section summary includes a list of Key Features. Also provided for each chapter are the following supplementary teaching aids to spur discussion and challenge the student’s knowledge of the material: Key Terms and Vocabulary, Questions, Primary and Alternate Source Analysis, Activities and Projects, and for some chapters, an Interdisciplinary Activity. -

Literary Award Gala

NASHVILLE PUBLIC LIBRARY LITERARY AWARD GALA NPLF.org LITERARY AWARD GALA The Nashville Public Library Literary Award was established in 2004 to recognize distinguished authors and other individuals for their contributions to the world of books and reading. Each year the award brings an outstanding individual to Nashville to honor his or her achievements, to benefit the library and to promote books and literacy. he NPL Literary Award weekend draws an audience T of nearly 1,000 cultural, political, community and business leaders from Nashville and beyond. Each year, the celebration begins with a Patrons Party. Often called “the best book club in town,” the annual gathering provides an intimate setting for guests to mingle, network and spark riveting conversation. The Literary Award Gala follows at the beautiful downtown library. The black-tie affair begins with cocktails in Ingram Hall and is followed by dinner and remarks from the honoree in the Grand Reading Room. Proceeds from the Literary Award’s Patrons Party and -John Lewis, 2016 Literary Award Honoree Gala benefit the Nashville Public Library Foundation’s mission to support and enhance the Literary Award Honorees Nashville Public Library. Elizabeth Gilbert, 2017 To learn more about sponsorship opportunities, please contact Amanda Tate: [email protected]. John Lewis, 2016 Jon Meacham, 2015 Scott Turow, 2014 Robert K. Massie, 2013 Margaret Atwood, 2012 John McPhee, 2011 Billy Collins, 2010 Doris Kearns Goodwin, 2009 John Irving, 2008 Ann Patchett, 2007 John Updike, 2006 David McCullough, 2005 David Halberstam, 2004 NPLF.org David Remnick 2018 Literary Award Honoree David Remnick has been the editor of The New Yorker since 1998 and a staff writer since 1992. -

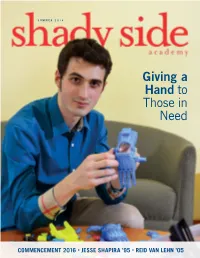

Giving a Hand to Those in Need

SUMMER 2016 Giving a Hand to Those in Need COMMENCEMENT 2016 • JESSE SHAPIRA ’95 • REID VAN LEHN ’05 Editor Lindsay Kovach Associate Editor Jennifer Roupe Contributors Val Brkich Christa Burneff Cristina Rouvalis Photography Commencement and feature photography by James Knox Additional photos provided by SSA faculty, staff, coaches, alumni, students and parents. Class notes photos are submitted by alumni and class correspondents. Design Kara Reid The following icons denote stories related to key goals Printing of SSA’s strategic vision, entitled Challenging Students to Broudy Printing Think Expansively, Act Ethically and Lead Responsibly. Shady Side Academy Magazine is published twice a year for Shady Side Academy alumni, parents and For more information, visit shadysideacademy.org/strategicvision. friends. Letters to the editor should be sent to Lindsay Kovach, Shady Side Academy, 423 Fox Chapel Rd., Academic Community Pittsburgh, PA 15238. Address corrections should be Program Connections sent to the Alumni & Development Office, Shady Side Academy, 423 Fox Chapel Rd., Pittsburgh, PA 15238. Junior School, 400 S. Braddock Ave., Physical Faculty Pittsburgh, PA 15221, 412-473-4400 Resources Middle School, 500 Squaw Run Road East, Pittsburgh, PA 15238, 412-968-3100 Financial Senior School, 423 Fox Chapel Rd., Students Sustainability Pittsburgh, PA 15238, 412-968-3000 www.shadysideacademy.org facebook.com/shadysideacademy twitter.com/shady_side youtube.com/shadysideacademy FSC to be placed by printer contentsSUMMER 2016 FEATURES ALSO IN THIS -

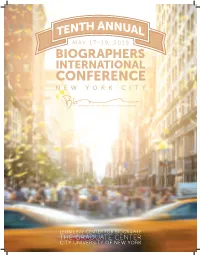

2019 BIO Program Rev3.Indd

MAY 17–1 9, 2019 BIOGRAPHERS INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE NEW YORK CITY LEON LEVY CENTER FOR BIOGRAPHY THE GRADUATE CENTER CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK The 2019 Plutarch Award Biographers International Organization is proud to present the Plutarch Award for the best biography of 2018, as chosen by our members. Congratulations to the ten nominees: The 2019 BIO Award Recipient: James McGrath Morris James McGrath Morris first fell in love with biography as a child reading newspaper obituaries. In fact, his steady diet of them be- came an important part of his education in history. In 2005, after a career as a journalist, an editor, a book publisher, and a school- teacher, Morris began writing books full-time. Among his works are Jailhouse Journalism: The Fourth Estate Behind Bars; The Rose Man of Sing Sing: A True Tale of Life, Murder, and Redemption in the Age of Yellow Journalism; Pulitzer: A Life in Politics, Print, and Power; Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, The First Lady of the Black Press, which was awarded the Benjamin Hooks National Book Prize for the best work in civil rights history in 2015; and The Ambulance Drivers: Hemingway, Dos Passos, and a Friendship Made and Lost in War. He is also the author of two Kindle Singles, The Radio Operator and Murder by Revolution. In 2016, he taught literary journalism at Texas A&M, and he has conducted writing workshops at various colleges, universities, and conferences. He is the progenitor of the idea for BIO and was among the found- ers as well as a past president. -

David Mccullough 2002

THE THEODORE H. WHITE LECTURE WITH DAVID MCCULLOUGH T HE T HEODORE H. W HITE L ECTURE WITH Joan Shorenstein Center ■ D PRESS POLITICS A VID M C C ULLOUGH PUBLIC POLICY Harvard University John F. Kennedy School of Government 2002 THE THEODORE H. WHITE LECTURE WITH DAVID MCCULLOUGH 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS History of the Theodore H. White Lecture ..................................................—5 Biography of David McCullough ..................................................................—7 Welcoming Remarks by Dean Joseph S. Nye, Jr. ........................................—9 Introduction by Alex S. Jones ..........................................................................—9 The 2002 Theodore H. White Lecture on Press and Politics “A Sense of History in Times of Crisis” by David McCullough ..........................................................................—11 The 2002 Theodore H. White Seminar on Press and Politics ..................—29 Alex S. Jones, Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy (moderator) Ann Compton, ABC News Walter Isaacson, CNN Alexander Keyssar, Harvard University David McCullough, Historian David Sanger, The New York Times THIRTEENTH ANNUAL THEODORE H. WHITE LECTURE 3 The Theodore H. White Lecture on Press and Politics commemorates the life of the late reporter and historian who created the style and set the standard for contemporary political journalism and campaign coverage. White, who began his journalism career delivering the Boston Post, entered Har- vard College in 1932 on a newsboy’s schol- arship. He studied Chinese history and Oriental languages. In 1939, he witnessed the bombing of Chungking while freelance reporting on a Sheldon Fellow- ship, and later explained, “Three thousand human beings died; once I’d seen that I knew I wasn’t going home to be a professor.” During the war, White covered East Asia for Time and returned to write Thunder Out of China, a controversial critique of the American-supported Nationalist Chinese government. -

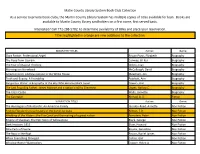

As a Service to Private Book Clubs, the Martin County Library System Has Multiple Copies of Titles Available for Loan

Matin County Library System Book Club Collection As a service to private book clubs, the Martin County Library System has multiple copies of titles available for loan. Books are available to Martin County library cardholders on a first come, first served basis. Interested? Call 772-288-5702 to determine availability of titles and place your reservation. Titles highlighted in orange are new additions to the collection. BIOGRAPHY TITLES Author: Genre: Clara Barton: Professional Angel Brown Pryor, Elizabeth Biography The Road from Coorain Conway, Jill Ker Biography The Year of Magical Thinking Didion, Joan Biography Mornings on Horseback McCullough, David Biography American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House Meacham, Jon Biography Truth and Beauty: A Friendship Patchett, Ann Biography Dangerous Water: A Biography of the Boy Who Became Mark Twain Powers, Ron Biography The Last Founding Father: James Monroe and a nation's call to Greatness Unger, Harlow C. Biography The Glass Castle Walls, Jannette Biography The Caretaker Ahmad, A. X. Fiction NONFICTION TITLES Author: Genre: The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family Gordon-Reed, Annette Non Fiction Finding Florida: the true history of the Sunshine State Allman, T.D. Non Fiction Wedding of the Waters: the Erie Canal and the making of a great nation Bernstein, Peter Non Fiction Empire of Shadows: The Epic Story of Yellowstone Black, George Non Fiction Dark Invasion: 1915 Blum, Howard Non Fiction Nine Parts of Desire Brooks, Geraldine Non Fiction The Boys in the Boat Brown, Daniel James Non Fiction When Everything Changed Collins, Gail Non Fiction Winslow Homer Watercolors Cooper, Helen A Non Fiction Brother, I'm Dying Danticat, Edwidge Non Fiction Duff, James H. -

Maya Angelou Robert Fĕ Asleson David Mccullough Barbara S

Baltimore ’86 Four other theme speakers highlight ACRL’s National Conference. Maya Angelou Robert Fĕ Asleson David McCullough Barbara S. Uehling Besides Alan C. Kay, whose profile appeared in writer, and playwright, and speaks six languages the October Cò-RL News, there are four other ma fluently. jor speakers on “Energies for Transition,” the Born in St. Louis, she spent most of her child theme of ACRL’s Fourth National Conference in hood with her grandmother in Stamps, Arkansas. Baltimore, April 9-12, 1986. Maya Angelou is an In 1940 she moved to San Francisco with her fam author, poet, playwright, professional stage and ily and worked a variety of jobs, writing poetry and screen performer and singer. Robert F. Asleson, studying dance and drama at night. In 1952 she re president of International Thomson Information, ceived a scholarship to study dance with Pearl Pri Inc., will speak on trends in publishing. David Mc mus in New York. Returning to San Francisco early Cullough, prizewinning historian and biographer in 1954, Angelou made her first professional ap and host of the popular “Smithsonian World” series pearance at the Purple Onion as a singer, then on PBS, will talk from the perspective of a scholarly joined the European touring company of Porgy consumer of library collections and services and and Bess as the lead dancer. will help identify transitions in American society. Angelou lived in Africa in the early 1960s. In Barbara S. Uehling, chancellor and professor of 1961 she became the associate editor of The Arab psychology at the University of Missouri, Colum Observer in Cairo, at that time the only English- bia, will speak from the perspective of an adminis language news weekly in the Middle East. -

Video Transcript

Video Transcript Lisa Bu: How books can open your mind So I was trained to become a gymnast for two years in Hunan, China in the 1970s. When I was in the first grade, the government wanted to transfer me to a school for athletes, all expenses paid. But my tiger mother said, "No." My parents wanted me to become an engineer like them. After surviving the Cultural Revolution, they firmly believed there's only one sure way to happiness: a safe and well-paid job. It is not important if I like the job or not. But my dream was to become a Chinese opera singer. That is me playing my imaginary piano. An opera singer must start training young to learn acrobatics, so I tried everything I could to go to opera school. I even wrote to the school principal and the host of a radio show. But no adults liked the idea. No adults believed I was serious. Only my friends supported me, but they were kids, just as powerless as I was. So at age 15, I knew I was too old to be trained. My dream would never come true. I was afraid that for the rest of my life some second-class happiness would be the best I could hope for. But that's so unfair. So I was determined to find another calling. Nobody around to teach me? Fine. I turned to books. I satisfied my hunger for parental advice from this book by a family of writers and musicians.["Correspondence in the Family of Fou Lei"] I found my role model of an independent woman when Confucian tradition requires obedience.["Jane Eyre"] And I learned to be efficient from this book.["Cheaper by the Dozen"] And I was inspired to study abroad after reading these. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Art and Life in America by Oliver W. Larkin Harvard Art Museums / Fogg Museum | Bush-Reisinger Museum | Arthur M

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Art and Life in America by Oliver W. Larkin Harvard Art Museums / Fogg Museum | Bush-Reisinger Museum | Arthur M. Sackler Museum. In this allegorical portrait, America is personified as a white marble goddess. Dressed in classical attire and crowned with thirteen stars representing the original thirteen colonies, the figure gives form to associations Americans drew between their democracy and the ancient Greek and Roman republics. Like most nineteenth-century American marble sculptures, America is the product of many hands. Powers, who worked in Florence, modeled the bust in plaster and then commissioned a team of Italian carvers to transform his model into a full-scale work. Nathaniel Hawthorne, who visited Powers’s studio in 1858, captured this division of labor with some irony in his novel The Marble Faun: “The sculptor has but to present these men with a plaster cast . and, in due time, without the necessity of his touching the work, he will see before him the statue that is to make him renowned.” Identification and Creation Object Number 1958.180 People Hiram Powers, American (Woodstock, NY 1805 - 1873 Florence, Italy) Title America Other Titles Former Title: Liberty Classification Sculpture Work Type sculpture Date 1854 Places Creation Place: North America, United States Culture American Persistent Link https://hvrd.art/o/228516 Location Level 2, Room 2100, European and American Art, 17th–19th century, Centuries of Tradition, Changing Times: Art for an Uncertain Age. Signed: on back: H. Powers Sculp. Henry T. Tuckerman, Book of the Artists: American Artist Life, Comprising Biographical and Critical Sketches of American Artists, Preceded by an Historical Account of the Rise and Progress of Art in America , Putnam (New York, NY, 1867), p.