David Mccullough 2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

Full List of Book Discussion Kits – September 2016

Full List of Book Discussion Kits – September 2016 1776 by David McCullough -(Large Print) Esteemed historian David McCullough details the 12 months of 1776 and shows how outnumbered and supposedly inferior men managed to fight off the world's greatest army. Abraham: A Journey to the Heart of Three Faiths by Bruce Feiler - In this timely and uplifting journey, the bestselling author of Walking the Bible searches for the man at the heart of the world's three monotheistic religions -- and today's deadliest conflicts. Abundance: a novel of Marie Antoinette by Sena Jeter Naslund - Marie Antoinette lived a brief--but astounding--life. She rebelled against the formality and rigid protocol of the court; an outsider who became the target of a revolution that ultimately decided her fate. After This by Alice McDermott - This novel of a middle-class American family, in the middle decades of the twentieth century, captures the social, political, and spiritual upheavals of their changing world. Ahab's Wife, or the Star-Gazer by Sena Jeter Naslund - Inspired by a brief passage in Melville's Moby-Dick, this tale of 19th century America explores the strong-willed woman who loved Captain Ahab. Aindreas the Messenger: Louisville, Ky, 1855 by Gerald McDaniel - Aindreas is a young Irish-Catholic boy living in gaudy, grubby Louisville in 1855, a city where being Irish, Catholic, German or black usually means trouble. The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho - A fable about undauntingly following one's dreams, listening to one's heart, and reading life's omens features dialogue between a boy and an unnamed being. -

ON the EFFECTIVE USE of PROXY WARFARE by Andrew Lewis Peek Baltimore, Maryland May 2021 © 2021 Andrew Peek All Rights Reserved

ON THE EFFECTIVE USE OF PROXY WARFARE by Andrew Lewis Peek A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland May 2021 2021 Andrew Peek All rights reserved Abstract This dissertation asks a simple question: how are states most effectively conducting proxy warfare in the modern international system? It answers this question by conducting a comparative study of the sponsorship of proxy forces. It uses process tracing to examine five cases of proxy warfare and predicts that the differentiation in support for each proxy impacts their utility. In particular, it proposes that increasing the principal-agent distance between sponsors and proxies might correlate with strategic effectiveness. That is, the less directly a proxy is supported and controlled by a sponsor, the more effective the proxy becomes. Strategic effectiveness here is conceptualized as consisting of two key parts: a proxy’s operational capability and a sponsor’s plausible deniability. These should be in inverse relation to each other: the greater and more overt a sponsor’s support is to a proxy, the more capable – better armed, better trained – its proxies should be on the battlefield. However, this close support to such proxies should also make the sponsor’s influence less deniable, and thus incur strategic costs against both it and the proxy. These costs primarily consist of external balancing by rival states, the same way such states would balance against conventional aggression. Conversely, the more deniable such support is – the more indirect and less overt – the less balancing occurs. -

Media Under Fire: Reporting Conflict in Iraq

INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND ADVICE FOR THE PARLIAMENT INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES Current Issues Brief No. 21 2002–03 Media Under Fire: Reporting Conflict in Iraq DEPARTMENT OF THE PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY ISSN 1440-2009 Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2003 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department of the Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribution to Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced, the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian government document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staff but not with members of the public. Published by the Department of the Parliamentary Library, 2003 I NFORMATION AND R ESEARCH S ERVICES Current Issues Brief No. 21 2002–03 Media Under Fire: Reporting Conflict in Iraq Sarah Miskin, Politics and Public Administration Group Laura Rayner and Maria Lalic, Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Group 24 March 2003 Acknowledgments Our thanks to Jack Waterford, Jane Hearn, Cathy Madden and Alex Tewes for their useful comments and contributions on earlier drafts of this paper. -

David Mccullough to Headline Special Talk at the History Center

Media Contacts: Ned Schano Brady Smith 412-454-6382 412-454-6459 [email protected] [email protected] David McCullough to Headline Special Talk at the History Center Focusing on the Steamboat Arabia -The two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning author will join History Center President and CEO Andy Masich and Steamboat Arabia excavator Dave Hawley for an engaging discussion- PITTSBURGH, Nov. 24, 2014 – The Senator John Heinz History Center will welcome America’s favorite historian and Pittsburgh native David McCullough for a special panel discussion on the importance of America’s river cities with History Center President and CEO Andy Masich and Arabia Steamboat Museum Director Dave Hawley on Tuesday, Dec. 2, at 11 a.m. Held in in conjunction with the museum’s newest exhibition, Pittsburgh’s Lost Steamboat: Treasures of the Arabia , the three historians will discuss Pittsburgh as the “Gateway to the West,” the region’s booming steamboat-building industry during the 19 th century, and the significance of the Arabia’s vast archaeological treasures. The Treasures of the Arabia exhibit features nearly 2,000 objects from the Steamboat Arabia’s massive cargo. In 1856, the Pittsburgh-built vessel carrying more than one million objects hit a snag and sank in the Missouri River. More than 130 years later, a group of modern day treasure hunters rediscovered the Arabia buried 45 feet below a cornfield a half-mile from the river. Remarkably, the anaerobic (oxygen- free) environment perfectly preserved most of the boat’s cargo in excellent condition, including fine dishware, clothing, and even bottled food such as pickles and ketchup. -

Huge Beirut Rally Rebuffs 'Gucci Revolution'

workers.org Workers and oppressed peoples of the world unite! MARCH 17, 2005 VOL. 47, NO. 9 50¢ •EEUU amenaza a presidente venezolano Lebanese reject •Tribunal: ‘No pena de muerte para jóvenes’ 12 U.S. intervention FIGHT FOR EMPIRE? Recruiting takes Huge Beirut rally rebuffs ‘Gucci revolution’ nose dive 3 By Fred Goldstein to the demands by the Bush administration and its allies and stooges that Syria remove its troops from Lebanon and that The Lebanese people converged on Beirut from all the poor Hezbollah be disarmed. areas of the country on March 6 in a massive anti-imperialist, Reuters of March 8, referring to a speech by Hezbollah leader anti-Zionist showing. They gave a resounding rebuff to efforts Sheikh Hassan Nasrallah, reported that “Nasrallah said no one by the Bush administration to isolate Syria, attack Hezbollah and in Lebanon feared the United States, whose troops left Beirut in set the stage for expanding its war for “regime change” in the 1984”—a few months after a car bombing which killed 241 Middle East to Damascus. Marines at their headquarters in Beirut. “We have defeated them WOMEN’S Organizers said 1 million demonstrated. Even the most mod- in the past and if they come again we will defeat them again,” he HISTORY erate estimate by the big business press was half a million. is reported to have said. Overhead panning of the demonstration by video cameras show- Placards at the rally, according to the AP, said “Syria & MONTH ing it overflowing Riyadh Solh Square in central Beirut for as far Lebanon brothers forever,” “America is the source of terrorism,” as the eye could see in all directions. -

David Mccullough

A teacher’s guide to DAVID C ULLOUGH M C WINNER OF THE PULITZER PRIZE TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 About the Author 1 Resources 1 Key Figures 2 Pre-Reading Knowledge 5 Part I, Chapter 1 6 Part I, Chapter 2 8 Part I, Chapter 3 11 Part II, Chapter 4 14 Part II, Chapter 5 17 Part III, Chapter 6 19 Part III, Chapter 7 22 INTRODUCTION Although the passage of the Declaration of Independence is a universally taught event in the United States, most high school students’ knowledge tends to be confined to the events that occurred in the city of Philadelphia during the month of July. In focusing on the events throughout the year of 1776, Pulitzer Prize–winning historian David McCullough gives students a deep understanding, from both sides of the conflict, of the events, people, and decisions that led to the creation of the United States. McCullough’s extensively researched work is filled with primary sources, reinforcing details and differing points of view on the events presented within the text, all of which makes 1776 an excellent text for use with the Common Core standards. This teacher’s guide provides a brief summary of 1776, divided by chapter and then subdivided by section. Each section summary includes a list of Key Features. Also provided for each chapter are the following supplementary teaching aids to spur discussion and challenge the student’s knowledge of the material: Key Terms and Vocabulary, Questions, Primary and Alternate Source Analysis, Activities and Projects, and for some chapters, an Interdisciplinary Activity. -

Literary Award Gala

NASHVILLE PUBLIC LIBRARY LITERARY AWARD GALA NPLF.org LITERARY AWARD GALA The Nashville Public Library Literary Award was established in 2004 to recognize distinguished authors and other individuals for their contributions to the world of books and reading. Each year the award brings an outstanding individual to Nashville to honor his or her achievements, to benefit the library and to promote books and literacy. he NPL Literary Award weekend draws an audience T of nearly 1,000 cultural, political, community and business leaders from Nashville and beyond. Each year, the celebration begins with a Patrons Party. Often called “the best book club in town,” the annual gathering provides an intimate setting for guests to mingle, network and spark riveting conversation. The Literary Award Gala follows at the beautiful downtown library. The black-tie affair begins with cocktails in Ingram Hall and is followed by dinner and remarks from the honoree in the Grand Reading Room. Proceeds from the Literary Award’s Patrons Party and -John Lewis, 2016 Literary Award Honoree Gala benefit the Nashville Public Library Foundation’s mission to support and enhance the Literary Award Honorees Nashville Public Library. Elizabeth Gilbert, 2017 To learn more about sponsorship opportunities, please contact Amanda Tate: [email protected]. John Lewis, 2016 Jon Meacham, 2015 Scott Turow, 2014 Robert K. Massie, 2013 Margaret Atwood, 2012 John McPhee, 2011 Billy Collins, 2010 Doris Kearns Goodwin, 2009 John Irving, 2008 Ann Patchett, 2007 John Updike, 2006 David McCullough, 2005 David Halberstam, 2004 NPLF.org David Remnick 2018 Literary Award Honoree David Remnick has been the editor of The New Yorker since 1998 and a staff writer since 1992. -

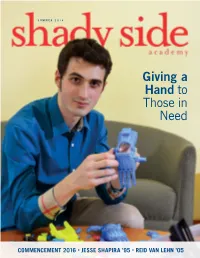

Giving a Hand to Those in Need

SUMMER 2016 Giving a Hand to Those in Need COMMENCEMENT 2016 • JESSE SHAPIRA ’95 • REID VAN LEHN ’05 Editor Lindsay Kovach Associate Editor Jennifer Roupe Contributors Val Brkich Christa Burneff Cristina Rouvalis Photography Commencement and feature photography by James Knox Additional photos provided by SSA faculty, staff, coaches, alumni, students and parents. Class notes photos are submitted by alumni and class correspondents. Design Kara Reid The following icons denote stories related to key goals Printing of SSA’s strategic vision, entitled Challenging Students to Broudy Printing Think Expansively, Act Ethically and Lead Responsibly. Shady Side Academy Magazine is published twice a year for Shady Side Academy alumni, parents and For more information, visit shadysideacademy.org/strategicvision. friends. Letters to the editor should be sent to Lindsay Kovach, Shady Side Academy, 423 Fox Chapel Rd., Academic Community Pittsburgh, PA 15238. Address corrections should be Program Connections sent to the Alumni & Development Office, Shady Side Academy, 423 Fox Chapel Rd., Pittsburgh, PA 15238. Junior School, 400 S. Braddock Ave., Physical Faculty Pittsburgh, PA 15221, 412-473-4400 Resources Middle School, 500 Squaw Run Road East, Pittsburgh, PA 15238, 412-968-3100 Financial Senior School, 423 Fox Chapel Rd., Students Sustainability Pittsburgh, PA 15238, 412-968-3000 www.shadysideacademy.org facebook.com/shadysideacademy twitter.com/shady_side youtube.com/shadysideacademy FSC to be placed by printer contentsSUMMER 2016 FEATURES ALSO IN THIS -

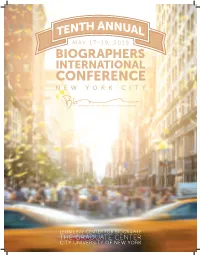

2019 BIO Program Rev3.Indd

MAY 17–1 9, 2019 BIOGRAPHERS INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE NEW YORK CITY LEON LEVY CENTER FOR BIOGRAPHY THE GRADUATE CENTER CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK The 2019 Plutarch Award Biographers International Organization is proud to present the Plutarch Award for the best biography of 2018, as chosen by our members. Congratulations to the ten nominees: The 2019 BIO Award Recipient: James McGrath Morris James McGrath Morris first fell in love with biography as a child reading newspaper obituaries. In fact, his steady diet of them be- came an important part of his education in history. In 2005, after a career as a journalist, an editor, a book publisher, and a school- teacher, Morris began writing books full-time. Among his works are Jailhouse Journalism: The Fourth Estate Behind Bars; The Rose Man of Sing Sing: A True Tale of Life, Murder, and Redemption in the Age of Yellow Journalism; Pulitzer: A Life in Politics, Print, and Power; Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, The First Lady of the Black Press, which was awarded the Benjamin Hooks National Book Prize for the best work in civil rights history in 2015; and The Ambulance Drivers: Hemingway, Dos Passos, and a Friendship Made and Lost in War. He is also the author of two Kindle Singles, The Radio Operator and Murder by Revolution. In 2016, he taught literary journalism at Texas A&M, and he has conducted writing workshops at various colleges, universities, and conferences. He is the progenitor of the idea for BIO and was among the found- ers as well as a past president. -

D:\Documents\Shauna's Documents\100 Best Nonfiction

Have You Read the 100 Best Nonfiction Books of the 20th Century? 1. The Education of Henry Adams, Henry Adams* 2. The Varieties of Religious Experience, William James* 3. Up from Slavery, Booker T. Washington* 4. A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf 5. Silent Spring, Rachel Damon 6. Selected Essays, 1917–1932, T. S. Eliot 7. The Double Helix, James D. Watson 8. Speak, Memory, Vladimir Nabokov 9. The American Language, H. L. Mencken 10. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, John Maynard Keynes 11. The Lives of a Cell, Lewis Thomas 12. The Frontier in American History, Frederick Jackson Turner 13. Black Boy, Richard Wright 14. Aspects of the Novel, E. M. Forster 15. The Civil War, Shelby Foote* 16. The Guns of August, Barbara Tuchman 17. The Proper Study of Mankind, Isaiah Berlin 16. The Nature and Destiny of Man, Reinhold Niebuhr 19. Notes of a Native Son, James Baldwin 20. The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, Gertrude Stein* 21. The Elements of Style, William Strunk and E. B. White 22. An American Dilemma, Gunnar Myrdal 23. Principia Mathematica, Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell 24. The Mismeasure of Man, Stephen Jay Gould 25. The Mirror and the Lamp, Meyer Howard Abrams 26. The Art of the Soluble, Peter B. Medawar 27. The Ants, Bert Hoelldobler and Edward O. Wilson 26. A Theory of Justice, John Rawls 29. Art and Illusion, Ernest H. Gombrich 30. The Making of the English Working Class, E. P. Thompson 31. The Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B. -

Maya Angelou Robert Fĕ Asleson David Mccullough Barbara S

Baltimore ’86 Four other theme speakers highlight ACRL’s National Conference. Maya Angelou Robert Fĕ Asleson David McCullough Barbara S. Uehling Besides Alan C. Kay, whose profile appeared in writer, and playwright, and speaks six languages the October Cò-RL News, there are four other ma fluently. jor speakers on “Energies for Transition,” the Born in St. Louis, she spent most of her child theme of ACRL’s Fourth National Conference in hood with her grandmother in Stamps, Arkansas. Baltimore, April 9-12, 1986. Maya Angelou is an In 1940 she moved to San Francisco with her fam author, poet, playwright, professional stage and ily and worked a variety of jobs, writing poetry and screen performer and singer. Robert F. Asleson, studying dance and drama at night. In 1952 she re president of International Thomson Information, ceived a scholarship to study dance with Pearl Pri Inc., will speak on trends in publishing. David Mc mus in New York. Returning to San Francisco early Cullough, prizewinning historian and biographer in 1954, Angelou made her first professional ap and host of the popular “Smithsonian World” series pearance at the Purple Onion as a singer, then on PBS, will talk from the perspective of a scholarly joined the European touring company of Porgy consumer of library collections and services and and Bess as the lead dancer. will help identify transitions in American society. Angelou lived in Africa in the early 1960s. In Barbara S. Uehling, chancellor and professor of 1961 she became the associate editor of The Arab psychology at the University of Missouri, Colum Observer in Cairo, at that time the only English- bia, will speak from the perspective of an adminis language news weekly in the Middle East.