Preliminary Geology and Petrography of Swat Kohistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SWAT SW15D00711-Onging Schemes of ADP 2015-16

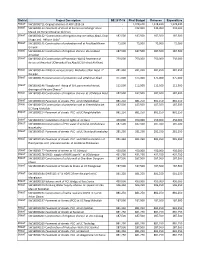

District Project Description BE 2017-18 Final Budget Releases Expenditure SWAT SW15D00711-Onging Schemes of ADP 2015-16 - 1,328,430 1,328,430 1,328,430 SWAT SW16D00113-Pavement of street at Parrai nearJehangir Abad - 332,000 332,000 332,000 Masjid UC Parrai COAsghar Ali Khan SWAT SW16D00132-"Construction of Irrigation channel atHaji Abad, Chail 187,500 187,500 187,500 187,500 Shagai and Akhoon Baba" SWAT SW16D00141-Construction of protection wall at FaizAbad Khwar 75,000 75,000 75,000 75,000 Ground SWAT SW16D00142-Construction of irrigation channel atFaiz Abad 187,500 187,500 187,500 187,500 Amankot SWAT SW16D00143-Construction of Protection Wall & Pavement of 750,000 750,000 750,000 750,000 streets at Amankot UCAmankot Faiz Abad (C/O Irshad Ali Khan) SWAT SW16D00144-DWSS at various streets Mohallas ofFaiz Abad 2” 281,250 281,250 281,250 281,250 dia pipe SWAT SW16D00145-Construction of protection wall atRahman Abad 375,000 375,000 375,000 375,000 SWAT SW16D00146-"Supply and fixing of Gril, pavementof street, 112,500 112,500 112,500 112,500 drainage at Maizaro Dherai " SWAT SW16D00149-Construction of irrigation channel at UCMalook Abad 187,500 187,500 187,500 187,500 SWAT SW16D00150-Pavement of streets PCC at UC MalookAbad 881,250 881,250 881,250 881,250 SWAT SW16D00153-Construction of protection wall at GreenMohallah 187,500 187,500 187,500 187,500 UC Rang Mohallah SWAT SW16D00154-Pavement of streets PCC at UC RangMohallah 881,250 881,250 881,250 881,250 SWAT SW16D00157-Installation of street lights at UC Bunr 450,000 450,000 450,000 450,000 -

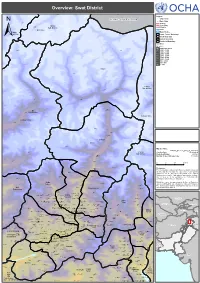

Swat District !

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Overview: Swat District ! ! ! ! SerkiSerki Chikard Legend ! J A M M U A N D K A S H M I R Citiy / Town ! Main Cities Lohigal Ghari ! Tertiary Secondary Goki Goki Mastuj Shahi!Shahi Sub-division Primary CHITRAL River Chitral Water Bodies Sub-division Union Council Boundary ± Tehsil Boundary District Boundary ! Provincial Boundary Elevation ! In meters ! ! 5,000 and above Paspat !Paspat Kalam 4,000 - 5,000 3,000 - 4,000 ! ! 2,500 - 3,000 ! 2,000 - 2,500 1,500 - 2,000 1,000 - 1,500 800 - 1,000 600 - 800 0 - 600 Kalam ! ! Utror ! ! Dassu Kalam Ushu Sub-division ! Usho ! Kalam Tal ! Utrot!Utrot ! Lamutai Lamutai ! Peshmal!Harianai Dir HarianaiPashmal Kalkot ! ! Sub-division ! KOHISTAN ! ! UPPER DIR ! Biar!Biar ! Balakot Mankial ! Chodgram !Chodgram ! ! Bahrain Mankyal ! ! ! SWAT ! Bahrain ! ! Map Doc Name: PAK078_Overview_Swat_a0_14012010 Jabai ! Pattan Creation Date: 14 Jan 2010 ! ! Sub-division Projection/Datum: Baranial WGS84 !Bahrain BahrainBarania Nominal Scale at A0 paper size: 1:135,000 Ushiri ! Ushiri Madyan ! 0 5 10 15 kms ! ! ! Beshigram Churrai Churarai! Disclaimers: Charri The designations employed and the presentation of material Tirat Sakhra on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Beha ! Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, Bar Thana Darmai Fatehpur city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the Kwana !Kwana delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Kalakot Matta ! Dotted line represents a!pproximately the Line of Control in Miandam Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. Sebujni Patai Olandar Paiti! Olandai! The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been Gowalairaj Asharay ! Wari Bilkanai agreed upon by the parties. -

51036-002: Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Cities Improvement Project

Environmental Impact Assessment (Draft) Project Number: 50136-002 February 2021 Pakistan: Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Cities Improvement Project Mingira Solid Waste Management Facility Development Main Report Prepared by Project Management Unit, Planning and Development Department, Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa for the Asian Development Bank. This draft environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section on ADB’s website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Environmental Impact Assessment Project Number: 51036-003 Loan Number: 6016-PAK February 2021 PAK: Mingora Solid Waste Management Facility (SWMF) Development Prepared by PMU - KPCIP for the Asian Development Bank (ADB) This Environmental Impact Assessment Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of the ADB website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgements as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

A New Travel Guide Book on Swat Valley

A new Travel Guide Book on Swat Valley Sustainable Tourism Foundation Pakistan (STFP) has published a new travel guide under the title of “Swat Valley Travel Guide and Hotel Directory”. The main focus of this travel guide is to promote eco-friendly recreational and adventure tourism and to provide updated information about the historical sites and tourist destinations in the beautiful Valley of Swat. This travel guide provides detailed and updated tourist information about Swat Valley with lots of breathtaking pictures. This travel guide is written by Aftab Rana who is a veteran traveler and hiker. He has has more than 25 years experience in the field of tourism and has also been working as a tourism development specialist in Swat Valley on a project for the revival of tourism in Swat under the auspicious of an international development agency. Amir Rashid who is also a keen traveler and excellent landscape photographer has brilliantly captured the scenic beauty of Swat Valley for this travel guide. This guide book has English and Udru editions (Urdu Edition is presently under print). It has description of more than 20 historical sites and more than 40 places of general tourist interest in Swat Valley including many new tourist spots which are introduced first time in this guide book. More than 8 lakes of Swat Valley (most of them are unknown) are also mentioned in this guide book. This 80 pages guide book has more than 80 high quality color photographs of tourist spots of Swat Valley and three sketch maps add value to this compact guidebook on this scenic Valley. -

The Dynamics of Public Perceptions and Climate Change in Swat Valley, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

sustainability Article The Dynamics of Public Perceptions and Climate Change in Swat Valley, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan Muhammad Suleman Bacha 1 , Muhammad Muhammad 2,3 , Zeyneb Kılıç 4,* and Muhammad Nafees 1 1 Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Peshawar, Peshawar 25000, Pakistan; [email protected] (M.S.B.); [email protected] (M.N.) 2 Department of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Peshawar, Peshawar 25000, Pakistan; [email protected] 3 Urban Policy and Planning Unit, Planning and Development Department, Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Peshawar 25000, Pakistan 4 Department of Civil Engineering, Adiyaman University, Adiyaman 02040, Turkey * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +90-5538135664 Abstract: With rising temperatures, developing countries are exposed to the horrors of climate change more than ever. The poor infrastructure and low adaptation capabilities of these nations are the prime concern of current studies. Pakistan is vulnerable to climate-induced hazards including floods, droughts, water shortages, shifts in weather patterns, loss of biodiversity, melting of glaciers, and more in the coming years. For marginal societies dependent on natural resources, adaptation becomes a challenge and the utmost priority. Within the above context, this study was designed to fill the existing research gap concerning public knowledge of climate vulnerabilities and respective adaptation strategies in the northern Hindukush–Himalayan region of Pakistan. Using the stratified sampling technique, 25 union councils (wards) were selected from the nine tehsils (sub-districts) of Citation: Bacha, M.S.; Muhammad, M.; the study area. Using the quantitative method approach, structured questionnaires were employed Kılıç, Z.; Nafees, M. The Dynamics of to collect data from 396 respondents. -

IEE: Pakistan

Initial Environmental Examination May 2012 PAK: Flood Emergency Reconstruction Project Prepared by National Highways Authority for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 31 May 2012) Currency unit – Pakistani Rupees (PRs) PRs1.00 = $0.01069 $1.00 = PRs93.53 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank AOI Area of Influence BOD Biological Oxygen Demand CMS Conservation of Migratory Species COD Chemical Oxygen Demand COSHH Control of Substances Hazardous to Health EC Electrical Conductivity EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EALS Environment Afforestation Land and Social EMP Environmental Management Plan EPA Environmental Protection Agency EPA’s Environmental Protection Agencies ESIA Environmental & Social Impact Assessment FAO Food and Agriculture Organization CA Cultivated Area GRC Grievance Redress Committee IEE Initial Environmental Examination M&E Monitoring and Evaluation NCS National Conservation Strategy NEQS National Environmental Quality Standards NOC No-Objection Certificate O&M Operation and Maintenance NHA National Highway Authority PEPA Pakistan Environmental Protection Act PEPC Pakistan Environmental Protections Council PHS Public Health and Safety PMU Project Management Unit PPE Personal Protective Equipment RSC Residual Sodium Carbonate SAR Sodium Adsorption Ratio SFA Social Frame Work Agreement SMO SCARPS Monitoring Organization SOP Survey of Pakistan SOP Soil Survey of Pakistan TDS Total Dissolved Solids US-EPA United States Environmental Protection Agency WAPDA Water and Power Development Authority WHO World Health Organization WWF Worldwide Fund for Nature NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and its agencies ends on 30 June. (ii) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. -

Threats to the Sustainability of Ethno-Medicinal Uses in Northern Pakistan (A Case Study of Miandam Valley, District Swat, NWFP

Volume 11(2) Threats to the sustainability of Ethno-Medicinal uses in Northern Pakistan (A Case Study of Miandam Valley, District Swat, NWFP Province, Pakistan) Threats to the sustainability of Ethno-Medicinal uses in Northern Pakistan (A Case Study of Miandam Valley, District Swat, NWFP Province, Pakistan) Sahibzada Muhammad Adnan1, Ashiq Ahmad Khan2, Abdul Latif & Zabta Khan Shiwari1 1 Kohat University of Science and Technology, Kohat, NWFP, Pakistan; 2 WWF-Pakistan, University Town Peshawar, NWFP, Pakista, * E-mail: [email protected] December 2006 Download at: http://www.lyonia.org/downloadPDF.php?pdfID=2.494.1 Threats to the sustainability of Ethno-Medicinal uses in Northern Pakistan (A Case Study of Miandam Valley, District Swat, NWFP Province, Pakistan) Abstract Miandam valley is best reprehensive of moist temperate forest geographically located 35, 02 N and 72, 33 E. The valley has over 300 plant species of which majority plants species are reported to be medicinal. The local community prepares medicines from these species through traditional way by using their indigenous knowledge for curing variety of disease. Decrease in medicinal plants has been observed in the last 30 years due to various threats and issues. Deforestation has been reported the main threat behind the declining trends of medicinal plants. The results shows that due to external pressures many plant species have been found endangered, rare and vulnerable. A high deforestation rate of 2% per year has been recorded over the last 30 years. Each year 8,053 trees are cutting in the valley for domestic and commercial consumption which is more than the actual yield provided by working circles and outside working circles areas. -

Exploring Patterns of Phytodiversity, Ethnobotany, Plant Geography and Vegetation in the Mountains of Miandam, Swat, Northern Pakistan

EXPLORING PATTERNS OF PHYTODIVERSITY, ETHNOBOTANY, PLANT GEOGRAPHY AND VEGETATION IN THE MOUNTAINS OF MIANDAM, SWAT, NORTHERN PAKISTAN BY Naveed Akhtar M. Phil. Born in Swat, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Academic Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in the Georg-August-University School of Science (GAUSS) under Faculty of Biology Program Biodiversity and Ecology Georg-August-University of Göttingen Göttingen, 2014 ZENTRUM FÜR BIODIVERSITÄT UND NACHHALTIGE LANDNUTZUNG SEKTION BIODIVERSITÄT, ÖKOLOGIE UND NATURSCHUTZ EXPLORING PATTERNS OF PHYTODIVERSITY, ETHNOBOTANY, PLANT GEOGRAPHY AND VEGETATION IN THE MOUNTAINS OF MIANDAM, SWAT, NORTHERN PAKISTAN Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultäten der Georg-August-Universität Göttingen Vorgelegt von M.Phil. Naveed Akhtar aus Swat, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan Göttingen, 2014 WHEN WE ARE FIVE AND THE APPLES ARE FOUR MY MOTHER SAYS “I DO NOT LIKE APPLES” DEDICATED TO My Mother Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Erwin Bergmeier Albrecht-von-Haller-Institute ofPlant Sciences Department of Vegetation & Phytodiversity Analysis Georg-August-University of Göttingen Untere Karspüle 2 37073, Göttingen, Germany Co-supervisor: Prof. Dr. Dirk Hölscher Department of Tropical Silviculture & Forest Ecology Georg-August-University of Göttingen Büsgenweg 1 37077, Göttingen, Germany Table of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................................ -

Short Communications

Short Communications Pakistan J. Zool., vol. 38(1), pp. 77-82, 2006. Ali and Ripley ( Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan , vol. 19, Oxford University NON-SONG BIRDS OF VALLEY Press, New Delhi, 1968-1974) have been followed SWAT: PAKISTAN for birds identification. However, help has also been taken from Roberts ( Compact handbook of The Abstract.- The checklist includes 38 non- birds of Pakistan , vol. 1, and 2) for distribution, song birds (Non-passeriformies) of the valley migration and status especially about the high Swat along with their key characters, status, specific locality, English and vernacular names. attitude birds unapproachable for us. Foraging, roosting, breeding, plumage and This work will help in reviewing the existing migratory characters are also being considered. database regarding birds of the valley Swat. Key words: Non-song birds, checklist, Swat. ENUMERATION OF THE BIRDS Valley Swat is situated in the North of Pakistan, 150 km away from Peshawar. It is 1. Alcedo atthis Linnaeus bounded on the west by the Malakand Agency and Small blue Kingfisher (E.*), Kir-keray, Mahi- District Dir, on the north by the District Chitral and khurak (Ver.**) Gilgit, on the east by Kohistan of the Northern areas A small graceful kingfisher with a large head, and District Mansehra and on the south by the short neck and stout bill. The bill is black, District Buner. Climate of the valley is moderate, straight and pointed like a dagger. Often January is the coldest month and June is the hottest. hover over open water and then suddenly Summer season temperature seldom rises 37°C . -

49050-001: Provincial Strategy for Inclusive and Sustainable Urban Growth

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 49050-001 December 2020 Islamic Republic of Pakistan: Provincial Strategy for Inclusive and Sustainable Urban Growth (Cofinanced by the Japan Fund for Poverty Reduction) Prepared by Saaf Consult (SC), Netherlands in association with dev-consult (DC), Pakistan For Planning and Development Department, Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. KP-SISUG Swat Regional Development Plan CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 01 December 2020) Currency unit – Pakistan Rupee (PKR) PKR1.00 = $0.0063 $1.00 = PKRs 159.4166 ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank ADP - annual development program APTMA - All Pakistan Textile Mills Association CDG - City District Government CDIA - Cities Development Initiative for Asia CIU - city implementation unit CLG - City Local Government CNG - compressed natural gas CPEC - China-Pakistan Economic Corridor CRVA - climate resilience and vulnerability assessment DDAC - District Development Advisory Committee DFID - Department for International Development (UK) DM - disaster management DRR - disaster risk reduction EA - executing agency EIA - environmental impact assessment EMP - environmental management plan EPA - Environmental Protection Agency [of Khyber PakHtunkHwa] -

Pseudoscorpions from the Mountains of Northern Pakistan (Arachnida: Pseudoscorpiones)

Arthropoda Selecta 13 (4): 225261 © ARTHROPODA SELECTA, 2004 Pseudoscorpions from the mountains of northern Pakistan (Arachnida: Pseudoscorpiones) Ëîæíîñêîðïèîíû ãîðíûõ ðàéîíîâ ñåâåðíîãî Ïàêèñòàíà (Arachnida: Pseudoscorpiones) Selvin Dashdamirov Ñåëüâèí Äàøäàìèðîâ Institut für Zoomorphologie, Zellbiologie und Parasitologie, Heinrich-Heine-Universit¬t, Universit¬tsstr. 1, Dòsseldorf 40225 Germany. E-mail: [email protected] KEY WORDS: Pseudoscorpiones, taxonomy, faunistics, distribution, ecology, new genus, new species, Pakistan. ÊËÞ×ÅÂÛÅ ÑËÎÂÀ: Pseudoscorpiones, òàêñîíîìèÿ, ôàóíèñòèêà, ýêîëîãèÿ, íîâûé ðîä, íîâûå âèäû, Ïàêèñòàí. ABSTRACT. The false-scorpion fauna of the mon- gen.n., sp.n. (Chernetidae). Äàíà íîâàÿ êîìáèíàöèÿ: tane parts of northern Pakistan is updated. At present it Bisetocreagris afghanica (Beier, 1959), comb.n. ex contains 30 species, including six new: Mundochtho- Microcreagris. Äëÿ áîëüøèíñòâà âèäîâ ïðèâîäÿòñÿ nius asiaticus sp.n., Tyrannochthonius oligochetus äåòàëüíûå ôàóíèñòè÷åñêèå è òàêñîíîìè÷åñêèå çà- sp.n., Rheoditella swetlanae sp.n., Allochernes minor ìå÷àíèÿ, à òàêæå èëëþñòðàöèè. Ðÿä îïðåäåëåíèé sp.n., Allochernes loebli sp.n. and Bipeltochernes pa- âûçûâàþò ñîìíåíèÿ, è äëÿ èõ óòî÷íåíèÿ íåîáõîäè- kistanicus gen.n., sp.n. (Chernetidae). Detailed faunis- ìû ðîäîâûå ðåâèçèè. Ôàóíà â îñíîâíîì ïàëåàðêòè- tic and taxonomic remarks as well as illustrations are ÷åñêàÿ, íî ïðèñóòñòâóþò è íåñêîëüêî îðèåíòàëü- provided to most of them. A new combination is pro- íûõ ýëåìåíòîâ. posed: Bisetocreagris afghanica (Beier, 1959), comb.n. ex Microcreagris. The identities of some species re- main insecure, because their respective genera require Introduction revision. The fauna is mostly Palaearctic, but a few Oriental elements are apparent as well. Pseudoscorpions from most parts of Central Asia are still poorly-known. This especially applies to the ZUSAMMENFASSUNG. -

Present State and Future Trends of Pine Forests of Malam Jabba, Swat District, Pakistan

Pak. J. Bot., 47(6): 2161-2169, 2015. PRESENT STATE AND FUTURE TRENDS OF PINE FORESTS OF MALAM JABBA, SWAT DISTRICT, PAKISTAN MUHAMMAD FAHEEM SIDDIQUI1, ARSALAN1, MOINUDDIN AHMED2, MUHAMMAD ISHTIAQ HUSSAIN3, JAVED IQBAL4AND MUHAMMAD WAHAB5 1Department of Botany, University of Karachi, 75270, Pakistan 2Indiana State University, Terre Haute, Indiana, USA 47809-1902 3Centre for Plant Conservation, University of Karachi, 75270, Pakistan 4Department of Botany, Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science and Technology, Karachi 5State Key Laboratory of Vegetation and Environmental Change, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100093, China *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract Present state and future trend of pine forests of Malam Jabba, Swat district, Pakistan explored. We focused on vegetation composition, structure, diversity and forests dynamics. Thirteen stands were sampled by Point Centered Quarter method. Among all stands four monospecific forests of Pinus wallichiana attained highest density ha-1 except in one stand where Picea smithiana attained 401 trees ha-1. Unlike density, the basal area m2 ha-1 of these stands varies stand to stand. Based on floristic composition and importance value index, five different communities viz Pinus wallichiana-Picea smithiana; Picea smithiana-Pinus wallichiana; Abies pindrow-Pinus wallichiana; Pinus wallichiana-Abies pindrow; Abies pindrow-Picea smithiana and 4 monospecific forests of Pinus wallichiana were recognized. Size class structure of forests showed marked influence of anthropogenic disturbance because not a single stand showed ideal regeneration pattern (inverse J shape distribution). Future of these forests is worst due to absence trees in small size classes. Gaps are also evident in most of the forest stands.