The Gang Beats the Odds: It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia's Consistent Popularity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

SIMPSONS to SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M

CONTEMPORARY ANIMATION: THE SIMPSONS TO SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M. Social Work 134 Instructor: Steven Pecchia-Bekkum Office Phone: 801-935-9143 E-Mail: [email protected] Office Hours: M-W 3:00 P.M.-5:00 P.M. (FMAB 107C) Course Description: Since it first appeared as a series of short animations on the Tracy Ullman Show (1987), The Simpsons has served as a running commentary on the lives and attitudes of the American people. Its subject matter has touched upon the fabric of American society regarding politics, religion, ethnic identity, disability, sexuality and gender-based issues. Also, this innovative program has delved into the realm of the personal; issues of family, employment, addiction, and death are familiar material found in the program’s narrative. Additionally, The Simpsons has spawned a series of animated programs (South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, Rick and Morty etc.) that have also been instrumental in this reflective look on the world in which we live. The abstraction of animation provides a safe emotional distance from these difficult topics and affords these programs a venue to reflect the true nature of modern American society. Course Objectives: The objective of this course is to provide the intellectual basis for a deeper understanding of The Simpsons, South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, and Rick and Morty within the context of the culture that nurtured these animations. The student will, upon successful completion of this course: (1) recognize cultural references within these animations. (2) correlate narratives to the issues about society that are raised. -

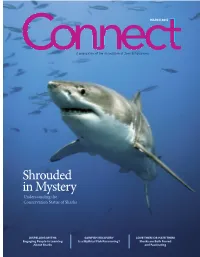

Shrouded in Mystery Understanding the Conservation Status of Sharks

MARCH 2015 A publication of the Association of Zoos & Aquariums Shrouded in Mystery Understanding the Conservation Status of Sharks DISPELLING MYTHS SAWFISH RECOVERY LOVE THEM OR HATE THEM Engaging People in Learning Is a Mythical Fish Recovering? Sharks are Both Feared About Sharks and Fascinating March 2015 Features 18 24 30 36 Shrouded in Mystery Dispelling Myths Sawfi sh Recovery Love Them or Hate Them The International Union for Through informative Once abundant in the Sharks are iconic animals Conservation of Nature Red displays, underwater waters of more than 90 that are both feared and List of Threatened Species tunnels, research, interactive countries around the world, fascinating. Misrepresented indicates that 181 of the touch tanks and candid sawfi sh are now extinct from in a wide array of media, the 1,041 species of sharks and conversations with guests, half of their former range, public often struggles to get rays are threatened with Association of Zoos and and all fi ve species are a clear understanding of the extinction, but the number Aquariums-accredited classifi ed as endangered complex and important role could be even higher. facilities have remarkable or critically endangered by that these remarkable fi sh play BY LANCE FRAZER ways of engaging people in the International Union for in oceans around the world. informal and formal learning. Conservation of Nature. BY DR. SANDRA ELVIN AND BY KATE SILVER BY EMILY SOHN DR. PAUL BOYLE March 2015 | www.aza.org 1 7 13 24 Member View Departments 7 County-Wide Survey 9 Pizzazz in Print 11 By the Numbers 44 Faces & Places Yields No Trace of Rare This Vancouver Aquarium ad AZA shark and ray 47 Calendar Western Pond Turtle was one of fi ve that ran as conservation. -

Family and Satire in Family Guy

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2015-06-01 Where Are Those Good Old Fashioned Values? Family and Satire in Family Guy Reilly Judd Ryan Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Ryan, Reilly Judd, "Where Are Those Good Old Fashioned Values? Family and Satire in Family Guy" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 5583. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/5583 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Where Are Those Good Old Fashioned Values? Family and Satire in Family Guy Reilly Judd Ryan A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Darl Larsen, Chair Sharon Swenson Benjamin Thevenin Department of Theatre and Media Arts Brigham Young University June 2015 Copyright © 2015 Reilly Judd Ryan All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Where Are Those Good Old Fashioned Values? Family and Satire in Family Guy Reilly Judd Ryan Department of Theatre and Media Arts, BYU Master of Arts This paper explores the presentation of family in the controversial FOX Network television program Family Guy. Polarizing to audiences, the Griffin family of Family Guy is at once considered sophomoric and offensive to some and smart and satiric to others. -

Computer Infections: from the Wild West to the New Sheriff Beware Of

April 2017 Volume 8, Issue 4 The Newsletter That’s Both Informative and Fun! Computer Infections: From the Wild West to the New Sheriff Is anti-virus software still relevant? Trick question. Computer viruses are not extinct. They are a vast and ever present danger. The issue at hand is whether or not stand-alone virus software is still I hope you enjoy this month’s necessary. newsletter! According to MakeTechEasier.com, the early days of computing were like Gene Rhodes the wild west for viruses, which often had no trouble spreading through email ServiceMaster Quality Services and downloads. Fast-forward to today, we see services such as Google and Microsoft's Kids Started this U.S. Easter Windows have top quality anti-virus capabilities built right in. In fact, keeping up-to-date frequently used services, especially the Tradition operating system, is often the best way to help prevent a virus outbreak. In the 1800s, the rolling lawns of the U.S. At work, protect the company networks by not plugging in unauthorized Capitol were an irresistible target for kids on Easter Monday. computers. Don't install unauthorized software. Don't share your password. One of the few days off for kids and adults, Easter Monday also included lots of leftover hard- boiled eggs. Beware of Questionable Spin Moves Naturally, the Capitol soon became the site of egg rolls, in which children would compete to see Millions love the heart-pounding, socializing of a spin class (stationary whose egg could roll farther without breaking. It cycling). became quite the thing. -

The Casting Director Guide from Now Casting, Inc

The Casting Director Guide From Now Casting, Inc. This printable Casting Director Guide includes CD listings exported from the CD Connection in NowCasting.com’s Contacts NOW area. The Guide is an easy way to get familiar with all the CD’s. Or, you might want to print a copy that lives in your car. Keep in mind that the printable CD Guide is created approximately once a month while the CD Connection is updated constantly. There will be info in the printable “Guide” that is out of date almost immediately… that’s the nature of casting. If you need a more comprehensive, timely and searchable research and marketing tool then you should consider using Contacts NOW in NowCasting.com. In Contacts NOW, you can search the CD database directly, make personal notes, create mailing lists, search Agents, make your own Custom Contacts and print labels. You can even export lists into Postcards NOW – a service that lets you create and mail postcards all from your desktop! You will find Contacts NOW in your main NowCasting menu under Get it NOW or Guides and Labels. Questions? Contact the NowCasting Staff @ 818-841-7165 Now Casting.com We’re Back! Many post hiatus updates! October ‘09 $13.00 Casting Director Guide Run BY Actors FOR Actors More UP- TO-THE-MINUTE information than ANY OTHER GUIDE Compare to the others with over 100 pages of information Got Casting Notices? We do! www.nowcasting.com WHY BUY THIS BOOK? Okay, there are other books on the market, so why should you buy this one? Simple. -

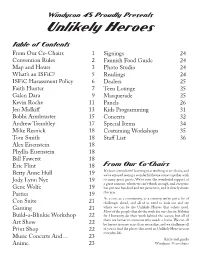

Download Program Book

Windycon 45 Proudly Presents Unlikely Heroes Table of Contents From Our Co-Chairs 1 Signings 24 Convention Rules 2 Fannish Food Guide 24 Map and Hours 3 Photo Studio 24 What’s an ISFiC? 5 Readings 24 ISFiC Harassment Policy 6 Dealers 25 Faith Hunter 7 Teen Lounge 25 Galen Dara 9 Masquerade 25 Kevin Roche 11 Panels 26 Jen Midkiff 13 Kids Programming 31 Bobbi Armbruster 15 Concerts 32 Andrew Trembley 17 Special Items 34 Mike Resnick 18 Costuming Workshops 35 Tom Smith 18 Staff List 36 Alex Eisenstein 18 Phyllis Eisenstein 18 Bill Fawcett 18 From Our Co-Chairs Eric Flint 18 It’s been a wonderful learning year working as co-chairs, and Betty Anne Hull 19 we’ve enjoyed seeing a wonderful theme come together with so many great guests. We’ve seen the wonderful support of Jody Lynn Nye 19 a great concom, whom we can’t thank enough, and everyone Gene Wolfe 19 has put one hundred and ten percent in, and it clearly shows Parties 19 this year. As a con, as a community, as a country, we’ve got a lot of Con Suite 21 challenges ahead, and all of us need to look out and see where we can be the Unlikely Heroes that others need. Gaming 21 Most of the people that do the work for our charity, Habitat Build-a-Blinkie Workshop 22 for Humanity, do their work behind the scenes, but all of them are heroes to someone who needs a home. We can all Art Show 22 be heroes in more ways than we realize, and we challenge all of you to find the places that need an Unlikely Hero in your Print Shop 22 everyday life. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE, Vol. 153, Pt. 19 October 3, 2007

October 3, 2007 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE, Vol. 153, Pt. 19 26339 b 1800 Today I’m introducing legislation to worrisome’’ by a former Pentagon cy- SPECIAL ORDERS rename the Fairdale, Kentucky, Post bersecurity expert, and as reported by Office the Lance Corporal Robert A. Bill Gertz in today’s Washington The SPEAKER pro tempore (Ms. Lynch Memorial Post Office, so that it Times, a current Pentagon official con- CLARKE). Under the Speaker’s an- may stand as a testament to his firmed, ‘‘Huawei is up to its eyeballs nounced policy of January 18, 2007, and heroics and strong character. For his with the Chinese military’’; while an- under a previous order of the House, selfless devotion to all of us in the other official stated ‘‘we are proposing the following Members will be recog- United States, he deserves our recogni- to sell the PLA a key to our front door. nized for 5 minutes each. tion and thanks. For their sacrifice, his This is a very dangerous trend.’’ f family deserves our support. We are This is not the first time Communist HONORING LANCE CORPORAL poorer for the loss of him but we, as a China’s Huawei Technologies has ROBERT LYNCH community and a country, are better raised legitimate American concerns. off for the short time we had him. In January 2006 Newsweek described The SPEAKER pro tempore. Under a Huawei Technologies as ‘‘a little too previous order of the House, the gen- I urge my colleagues to join me today in honoring Lance Corporal Rob- obsessed with acquiring advanced tech- tleman from Kentucky (Mr. -

A Crooked King with a Crooked Back

August 8, 2017 The Our 24th Year of Publishing FREE Weekly (979) 849-5407 PLEASE mybulletinnewspaper.com © 2017 TAKE ONE LAKE JACKSON Bulletin• CLUTE • RICHWOOD • FREEPORT • OYSTER CREEK • ANGLETON DANBURY • ALVIN • WEST COLUMBIA • BRAZORIA • SWEENY A crooked Baseball the king with a old fashioned crooked back way – no A/C By Ron Rozelle By John Toth Contributing Editor Editor and Publisher Well, you might have heard on I’m sitting in Kauffman Stadium the news or read in the paper a in Kansas City, waiting for the few years ago that they’ve found sun to set so the temperature can King Richard the Third. go back down to the low 90s. I don’t know about you, but I This is a grand stadium, but was getting awfully worried. After there is something missing – a all, he’d been missing for over dome. Air conditioning would be 500 years. And they hadn’t even nice also. put out an Of course, we have to walk Amber alert. all around It turns out the place so he’d been in that I can see the park- everything in ing lot of a UW donates $100,000 to S.F.A for mental health work one visit. Who grocery store Stephen F. Austin Commu- to care for residents and enable the uninsured. knows when in Leicester, I’ll be return- THE WORDSMITH nity Health Network received them to live healthier lives. Its main locations are found in a small city $100,000 from the United Way Stephen F. Austin Community Alvin and Freeport. -

Ending on a Sour… Er… Sober Note?” Nehemiah 13:4-31 31 August 2014

“Ending On a Sour… Er… Sober Note?” Nehemiah 13:4-31 31 August 2014 Maybe you’ve heard the expression, “Jump the shark.” It is a phrase that was originally used to denote the tipping point at which a TV series is deemed by the viewers to have passed its peak, or has introduced plot twists that are logically inconsistent in terms of everything that has preceded them. Once a show has “jumped the shark,” the viewer senses a noticeable decline in quality or feels the show has undergone too many changes to retain its original charm. The term has also evolved to describe other areas of pop culture where people, actors, authors, etc seem to lose their edge and they are on an obvious decline. Where did the phrase “jump the shark” originate? The term comes from a Happy Days episode centering around Arthur Fonzarelli, also known as Fonzie, or the Fonz. Remember Fonzie? Fonzie was the cool, womanizer who could woo all the ladies with his love and looks. Fonzie would take your girl right outta your arms just by looking at her! He was that cool! Straight out of your arms into the arms of the Fonz. Well, there is an episode of Happy Days where the Fonz is waterskiing in the ocean, with perfect hair and wearing his famous leather jacket, and he jumps over a shark in the ocean. So the Fonz is waterskiing in the ocean, he sees a shark fin, the viewer is terrified because we think the Fonz is gonna get eaten by a shark, and what does Fonzie do? He does what only the Fonz could do: he jumps over the shark! Hence, the expression, “jump the shark.” That episode was the beginning of the end for Happy Days. -

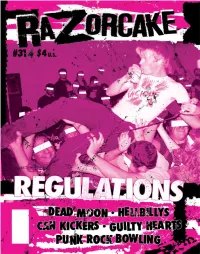

Razorcake Issue #31 As A

was on my back at the bottom of an abandoned swimming pool after Some of them die. Then ants eat them. My leg felt a tingle; I pulled it out an hour of skating, hoping the pain would subside. I heard a wet from under the desk, and saw that there were about one hundred ants on snap and didn’t want to look. I hadn’t been getting rad. I was just and inside the cast. I got a flashlight to see where they were concentrat- I returning to the shallow end, something I’ve done thousands of ed and smacked my forehead on the edge of my desk when I leaned times. When I looked, my foot was pointing in the wrong direction and down. For the first time in a long while, I felt crushed. I felt like quitting. was slowly trying to correct itself. My back foot had slipped off my skate- All of this: the zine, the books, the non-profit. Kaput. Done. Get a job, board and I’d run over my ankle. This was mid September. We’d literally work for someone else. I’d given it my shot and it felt like I’d been beat- dropped off the last Razorcakes for our bi-monthly big mailout hours en by hammers. before. As a treat to myself for working so hard, I’d planned a week-long My friends and family wouldn’t let me go. Chris Devlin drove me “vacation at home,” where I didn’t have anything solid planned except to physical therapy and to get my pain medication, while learning new skating new places, reading, listening to music, and hanging out. -

Familyguy Script

1 EXT. CHURCH PARKING LOT 1 The parking lot is filled with parked cars, including the Griffin’s, everyone is inside the church. CUT TO: 2 INT. CHURCH 2 The entire CONGREGATION, including the GRIFFINS are sitting in the pews waiting for mass to start. LOIS (To Peter.) Peter, it sure has been a while. Where do you think the Preacher could be? PETER (Looks around.) I don’t know. I’ll go see if I can find him. Come on Chris. PETER and CHRIS leave the isle and head to the back of the church. CUT TO: 3 EXT. BACK OF CHURCH 3 The PREACHER is sitting in the gutter crying and drinking alcohol. PETER Uh. Hey, you’re late for mass. PREACHER I’m not sure if I think there is even a God anymore. I mean, I’ve been praying to him for over 40 years and not one of my prayers were answered. God doesn’t exist! CHRIS Is that true dad? PETER No Chris. Of course there is a God. But you have to see it from his point of view. (MORE) (CONTINUED) 2. 3 CONTINUED: 3 PETER (CONT'D) I mean, if you think about it, God is basically watching us like a TV show. Do you honestly think he can sit there for over 4,000 years watching the same thing? God only knows what he’s doing now. CAMERA PULLS UP INTO THE SKY, THROUGH THE CLOUDS, REVEALING HEAVEN WHERE GOD AND JESUS ARE PLAYING FOOSBALL. IN THE BACKGROUND THERE IS A SCORE BOARD GOD IS WINNING 37 TO 0 AND A “RULES” BOARD IS FLOATING NEXT TO IT WHICH SAYS “RULE #1 : NO DIVINE POWERS”.