Copyrights Retold: How Interpretive Rights Foster Creativity and Justify Fan-Based Activities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

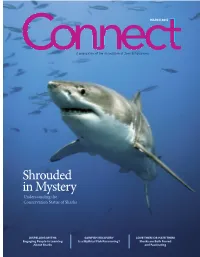

Shrouded in Mystery Understanding the Conservation Status of Sharks

MARCH 2015 A publication of the Association of Zoos & Aquariums Shrouded in Mystery Understanding the Conservation Status of Sharks DISPELLING MYTHS SAWFISH RECOVERY LOVE THEM OR HATE THEM Engaging People in Learning Is a Mythical Fish Recovering? Sharks are Both Feared About Sharks and Fascinating March 2015 Features 18 24 30 36 Shrouded in Mystery Dispelling Myths Sawfi sh Recovery Love Them or Hate Them The International Union for Through informative Once abundant in the Sharks are iconic animals Conservation of Nature Red displays, underwater waters of more than 90 that are both feared and List of Threatened Species tunnels, research, interactive countries around the world, fascinating. Misrepresented indicates that 181 of the touch tanks and candid sawfi sh are now extinct from in a wide array of media, the 1,041 species of sharks and conversations with guests, half of their former range, public often struggles to get rays are threatened with Association of Zoos and and all fi ve species are a clear understanding of the extinction, but the number Aquariums-accredited classifi ed as endangered complex and important role could be even higher. facilities have remarkable or critically endangered by that these remarkable fi sh play BY LANCE FRAZER ways of engaging people in the International Union for in oceans around the world. informal and formal learning. Conservation of Nature. BY DR. SANDRA ELVIN AND BY KATE SILVER BY EMILY SOHN DR. PAUL BOYLE March 2015 | www.aza.org 1 7 13 24 Member View Departments 7 County-Wide Survey 9 Pizzazz in Print 11 By the Numbers 44 Faces & Places Yields No Trace of Rare This Vancouver Aquarium ad AZA shark and ray 47 Calendar Western Pond Turtle was one of fi ve that ran as conservation. -

Aachi Wa Ssipak Afro Samurai Afro Samurai Resurrection Air Air Gear

1001 Nights Burn Up! Excess Dragon Ball Z Movies 3 Busou Renkin Druaga no Tou: the Aegis of Uruk Byousoku 5 Centimeter Druaga no Tou: the Sword of Uruk AA! Megami-sama (2005) Durarara!! Aachi wa Ssipak Dwaejiui Wang Afro Samurai C Afro Samurai Resurrection Canaan Air Card Captor Sakura Edens Bowy Air Gear Casshern Sins El Cazador de la Bruja Akira Chaos;Head Elfen Lied Angel Beats! Chihayafuru Erementar Gerad Animatrix, The Chii's Sweet Home Evangelion Ano Natsu de Matteru Chii's Sweet Home: Atarashii Evangelion Shin Gekijouban: Ha Ao no Exorcist O'uchi Evangelion Shin Gekijouban: Jo Appleseed +(2004) Chobits Appleseed Saga Ex Machina Choujuushin Gravion Argento Soma Choujuushin Gravion Zwei Fate/Stay Night Aria the Animation Chrno Crusade Fate/Stay Night: Unlimited Blade Asobi ni Iku yo! +Ova Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai! Works Ayakashi: Samurai Horror Tales Clannad Figure 17: Tsubasa & Hikaru Azumanga Daioh Clannad After Story Final Fantasy Claymore Final Fantasy Unlimited Code Geass Hangyaku no Lelouch Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children B Gata H Kei Code Geass Hangyaku no Lelouch Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within Baccano! R2 Freedom Baka to Test to Shoukanjuu Colorful Fruits Basket Bakemonogatari Cossette no Shouzou Full Metal Panic! Bakuman. Cowboy Bebop Full Metal Panic? Fumoffu + TSR Bakumatsu Kikansetsu Coyote Ragtime Show Furi Kuri Irohanihoheto Cyber City Oedo 808 Fushigi Yuugi Bakuretsu Tenshi +Ova Bamboo Blade Bartender D.Gray-man Gad Guard Basilisk: Kouga Ninpou Chou D.N. Angel Gakuen Mokushiroku: High School Beck Dance in -

Computer Infections: from the Wild West to the New Sheriff Beware Of

April 2017 Volume 8, Issue 4 The Newsletter That’s Both Informative and Fun! Computer Infections: From the Wild West to the New Sheriff Is anti-virus software still relevant? Trick question. Computer viruses are not extinct. They are a vast and ever present danger. The issue at hand is whether or not stand-alone virus software is still I hope you enjoy this month’s necessary. newsletter! According to MakeTechEasier.com, the early days of computing were like Gene Rhodes the wild west for viruses, which often had no trouble spreading through email ServiceMaster Quality Services and downloads. Fast-forward to today, we see services such as Google and Microsoft's Kids Started this U.S. Easter Windows have top quality anti-virus capabilities built right in. In fact, keeping up-to-date frequently used services, especially the Tradition operating system, is often the best way to help prevent a virus outbreak. In the 1800s, the rolling lawns of the U.S. At work, protect the company networks by not plugging in unauthorized Capitol were an irresistible target for kids on Easter Monday. computers. Don't install unauthorized software. Don't share your password. One of the few days off for kids and adults, Easter Monday also included lots of leftover hard- boiled eggs. Beware of Questionable Spin Moves Naturally, the Capitol soon became the site of egg rolls, in which children would compete to see Millions love the heart-pounding, socializing of a spin class (stationary whose egg could roll farther without breaking. It cycling). became quite the thing. -

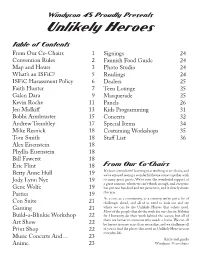

Download Program Book

Windycon 45 Proudly Presents Unlikely Heroes Table of Contents From Our Co-Chairs 1 Signings 24 Convention Rules 2 Fannish Food Guide 24 Map and Hours 3 Photo Studio 24 What’s an ISFiC? 5 Readings 24 ISFiC Harassment Policy 6 Dealers 25 Faith Hunter 7 Teen Lounge 25 Galen Dara 9 Masquerade 25 Kevin Roche 11 Panels 26 Jen Midkiff 13 Kids Programming 31 Bobbi Armbruster 15 Concerts 32 Andrew Trembley 17 Special Items 34 Mike Resnick 18 Costuming Workshops 35 Tom Smith 18 Staff List 36 Alex Eisenstein 18 Phyllis Eisenstein 18 Bill Fawcett 18 From Our Co-Chairs Eric Flint 18 It’s been a wonderful learning year working as co-chairs, and Betty Anne Hull 19 we’ve enjoyed seeing a wonderful theme come together with so many great guests. We’ve seen the wonderful support of Jody Lynn Nye 19 a great concom, whom we can’t thank enough, and everyone Gene Wolfe 19 has put one hundred and ten percent in, and it clearly shows Parties 19 this year. As a con, as a community, as a country, we’ve got a lot of Con Suite 21 challenges ahead, and all of us need to look out and see where we can be the Unlikely Heroes that others need. Gaming 21 Most of the people that do the work for our charity, Habitat Build-a-Blinkie Workshop 22 for Humanity, do their work behind the scenes, but all of them are heroes to someone who needs a home. We can all Art Show 22 be heroes in more ways than we realize, and we challenge all of you to find the places that need an Unlikely Hero in your Print Shop 22 everyday life. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE, Vol. 153, Pt. 19 October 3, 2007

October 3, 2007 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE, Vol. 153, Pt. 19 26339 b 1800 Today I’m introducing legislation to worrisome’’ by a former Pentagon cy- SPECIAL ORDERS rename the Fairdale, Kentucky, Post bersecurity expert, and as reported by Office the Lance Corporal Robert A. Bill Gertz in today’s Washington The SPEAKER pro tempore (Ms. Lynch Memorial Post Office, so that it Times, a current Pentagon official con- CLARKE). Under the Speaker’s an- may stand as a testament to his firmed, ‘‘Huawei is up to its eyeballs nounced policy of January 18, 2007, and heroics and strong character. For his with the Chinese military’’; while an- under a previous order of the House, selfless devotion to all of us in the other official stated ‘‘we are proposing the following Members will be recog- United States, he deserves our recogni- to sell the PLA a key to our front door. nized for 5 minutes each. tion and thanks. For their sacrifice, his This is a very dangerous trend.’’ f family deserves our support. We are This is not the first time Communist HONORING LANCE CORPORAL poorer for the loss of him but we, as a China’s Huawei Technologies has ROBERT LYNCH community and a country, are better raised legitimate American concerns. off for the short time we had him. In January 2006 Newsweek described The SPEAKER pro tempore. Under a Huawei Technologies as ‘‘a little too previous order of the House, the gen- I urge my colleagues to join me today in honoring Lance Corporal Rob- obsessed with acquiring advanced tech- tleman from Kentucky (Mr. -

Magicalg Burst

Magical g Burst a game of desperate magical girls Second Draft (2.1) ©2011 by Ewen Cluney Thanks to: Judgment and Anonymous from /tg/, Kurt, Joshua Gervais, Joe Iglesias, Jonathan Davis, and the folks on #becomethemeguca Intro Comic ................................................................................................................................................................2 Introduction ...............................................................................................................................................................4 A Magical World ........................................................................................................................................................6 Creating Your Magical Girl .........................................................................................................................................8 Playing the Game .....................................................................................................................................................11 The Game Master's Job .............................................................................................................................................28 Appendix 1: Random Tables .....................................................................................................................................35 Appendix 2: Addendum ............................................................................................................................................42 -

A Crooked King with a Crooked Back

August 8, 2017 The Our 24th Year of Publishing FREE Weekly (979) 849-5407 PLEASE mybulletinnewspaper.com © 2017 TAKE ONE LAKE JACKSON Bulletin• CLUTE • RICHWOOD • FREEPORT • OYSTER CREEK • ANGLETON DANBURY • ALVIN • WEST COLUMBIA • BRAZORIA • SWEENY A crooked Baseball the king with a old fashioned crooked back way – no A/C By Ron Rozelle By John Toth Contributing Editor Editor and Publisher Well, you might have heard on I’m sitting in Kauffman Stadium the news or read in the paper a in Kansas City, waiting for the few years ago that they’ve found sun to set so the temperature can King Richard the Third. go back down to the low 90s. I don’t know about you, but I This is a grand stadium, but was getting awfully worried. After there is something missing – a all, he’d been missing for over dome. Air conditioning would be 500 years. And they hadn’t even nice also. put out an Of course, we have to walk Amber alert. all around It turns out the place so he’d been in that I can see the park- everything in ing lot of a UW donates $100,000 to S.F.A for mental health work one visit. Who grocery store Stephen F. Austin Commu- to care for residents and enable the uninsured. knows when in Leicester, I’ll be return- THE WORDSMITH nity Health Network received them to live healthier lives. Its main locations are found in a small city $100,000 from the United Way Stephen F. Austin Community Alvin and Freeport. -

Ending on a Sour… Er… Sober Note?” Nehemiah 13:4-31 31 August 2014

“Ending On a Sour… Er… Sober Note?” Nehemiah 13:4-31 31 August 2014 Maybe you’ve heard the expression, “Jump the shark.” It is a phrase that was originally used to denote the tipping point at which a TV series is deemed by the viewers to have passed its peak, or has introduced plot twists that are logically inconsistent in terms of everything that has preceded them. Once a show has “jumped the shark,” the viewer senses a noticeable decline in quality or feels the show has undergone too many changes to retain its original charm. The term has also evolved to describe other areas of pop culture where people, actors, authors, etc seem to lose their edge and they are on an obvious decline. Where did the phrase “jump the shark” originate? The term comes from a Happy Days episode centering around Arthur Fonzarelli, also known as Fonzie, or the Fonz. Remember Fonzie? Fonzie was the cool, womanizer who could woo all the ladies with his love and looks. Fonzie would take your girl right outta your arms just by looking at her! He was that cool! Straight out of your arms into the arms of the Fonz. Well, there is an episode of Happy Days where the Fonz is waterskiing in the ocean, with perfect hair and wearing his famous leather jacket, and he jumps over a shark in the ocean. So the Fonz is waterskiing in the ocean, he sees a shark fin, the viewer is terrified because we think the Fonz is gonna get eaten by a shark, and what does Fonzie do? He does what only the Fonz could do: he jumps over the shark! Hence, the expression, “jump the shark.” That episode was the beginning of the end for Happy Days. -

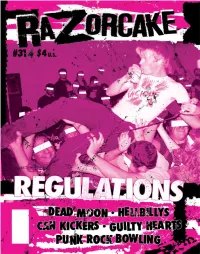

Razorcake Issue #31 As A

was on my back at the bottom of an abandoned swimming pool after Some of them die. Then ants eat them. My leg felt a tingle; I pulled it out an hour of skating, hoping the pain would subside. I heard a wet from under the desk, and saw that there were about one hundred ants on snap and didn’t want to look. I hadn’t been getting rad. I was just and inside the cast. I got a flashlight to see where they were concentrat- I returning to the shallow end, something I’ve done thousands of ed and smacked my forehead on the edge of my desk when I leaned times. When I looked, my foot was pointing in the wrong direction and down. For the first time in a long while, I felt crushed. I felt like quitting. was slowly trying to correct itself. My back foot had slipped off my skate- All of this: the zine, the books, the non-profit. Kaput. Done. Get a job, board and I’d run over my ankle. This was mid September. We’d literally work for someone else. I’d given it my shot and it felt like I’d been beat- dropped off the last Razorcakes for our bi-monthly big mailout hours en by hammers. before. As a treat to myself for working so hard, I’d planned a week-long My friends and family wouldn’t let me go. Chris Devlin drove me “vacation at home,” where I didn’t have anything solid planned except to physical therapy and to get my pain medication, while learning new skating new places, reading, listening to music, and hanging out. -

Reality Bonsai Animism and Science-Fiction As a Blueprint for Media Art in Contemporary Japan

Reality Bonsai Animism and Science-Fiction as a Blueprint for Media Art in Contemporary Japan Mauro Arrighi A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Southampton Solent University for the degree of Master of Philosophy March 2018 ‘This work is the intellectual property of Mauro Arrighi. You may copy up to 5% of this work for private study, or personal, non-commercial research. Any re-use of the information contained within this document should be fully referenced, quoting the author, title, university, degree level and pagination. Queries or requests for any other use, or if a more substantial copy is required, should be directed in the owner(s) of the Intellectual Property Rights’. Table of Contents Section 1 1 Abstract………………………………………………………………………………...........3 2 Introduction…………………………………………………………………….....................4 2.1 Aims.....………………………………………………………………………........9 3 Research Methods…………………………………………………………………….........10 4 Literature Survey…………………………………………………………………………..12 5 Historical and Theoretical Frameworks that Inform Japanese Media Art……………........22 6 Convergence of the Real and the Virtual in Japanese Society 6.1 The Relationship Between Escapism and Media Art...………..............................25 7 Case study: Media Artist Takahiro Hayakawa…………………...…...……….……...........35 8 Case study: Media Artist Kazuhiko Hachiya………………………………………..…......38 9 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….............43 10 List of Illustrations……………………………………………………………………......44 Section 2 1 Evidence of Practical work……………………………………………………....................47 -

Wealth Maximization Strategies* That Have “Jumped the Shark”

Certified Financial Services, LLC 600 Parsippany Road Suite 200 Parsippany, NJ 07054 Richard Aronwald Creative Financial Specialist wealth maximization strategies* www.richardaronwald.com May 2017 Financial Ideas (401k's/Student Loans) In September 1977, the hit TV show “Happy Days” started its fifth season. Since its debut, the situation comedy about 1950s-era high schoolers had seen a once-minor character, Arthur Fonzarelli – “the Fonz” – become a pop-culture icon for That his leather jacket and cool demeanor. The season-opening episode began with the central characters visiting Los Angeles, Have where, in response to a dare, the Fonz was about to jump a shark – wearing water skis and his leather jacket. “Jumped For many fans and critics, this ludicrous plot development marked a turning point. While “Happy Days” would continue for the another seven years, they felt the show was different – and not as good – compared to the first five seasons. Shark” In 1985, radio personality Jon Hein coined the term “jumping the shark” for the moment a once-popular TV show starts to lose its way. Today, the phrase has expanded to any event or idea “that is believed to be past its peak in quality or relevance.” Just because something has jumped the shark doesn’t mean it’s gone, or that some people don’t see benefit in it. But as Hein put it, “You know from now on, it’s all downhill…it will never be the same.” Hmm… “ideas that are believed to be past their peak in quality or relevance.” That sounds like a provocative starting point for some personal finance commentary. -

Alyssa Michaud Department of Music Research Schulich School Of

AFTER THE MUSIC BOX: A HISTORY OF AUTOMATION IN REAL-TIME MUSICAL PERFORMANCE Alyssa Michaud Department of Music Research Schulich School of Music McGill University, Montreal August 2019 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology © Alyssa Michaud 2019 i TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ iii Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... v Résumé .......................................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ ix Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Music and Technology: An Overview ........................................................................................ 7 Research Methods and Chapter Breakdown ............................................................................. 20 Who are the Mechanics? ........................................................................................................... 20 Chapter 1: The Player Piano: From Domestic Machine to Expressive Instrument .....................