Delivering Constitutional Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Colloquium on Education: British and American Perspectives (4Th, Swansea, Wales, United Kingdom, May 22-24, 1995)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 403 238 SP 037 098 TITLE International Colloquium on Education: British and American Perspectives (4th, Swansea, Wales, United Kingdom, May 22-24, 1995). Proceedings. INSTITUTION Wales Univ., Swansea. Dept. of Education. REPORT NO ISBN-0-90094-438-2 PUB DATE May 95 NOTE 148p. PUB TYPE Collected Works Conference Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Action Research; *College School Cooperation; Cooperative Learning; Educational Change; *Educational Environment; *Educational Policy; Educational Research; Elementary Secondary Education; English (Second Language); Foreign Countries; Higher Education; High Risk Students; Inservice Teacher Education; *Instructional Leadership; Language Minorities; Mathematics Education; Minority Group Teachers; *Partnerships in Education; Standards; Student Evaluation IDENTIFIERS United States; University of Wales Swansea; University of Wisconsin la Crosse; Wales ABSTRACT This collection of studies represents collaboration between the Departments of Education of theUniversity of Wales Swansea and the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. The papers are as follows: (1) "Analysing the Social Climate of Schools andClassrooms" (Robert W. Bilby);(2) "Reading Whose World?" (Diane Cannon);(3) "The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics' Standards:Systemic Change for the Twenty-first Century" (M. ElizabethCason); (4) "Developing Baseline Assessment: A Useful Tool or.a NecessaryEvil?" (Gill Harper-Jones);(5) "A Critical Analysis of Identification, Evaluation, Placement and Programming Processes for Studentsin the United States Who Are Identified as Having ExceptionalNeeds" (Hal Hiebert); (6) "The Effects of Recent Government Policy on the Provision of English Language Instruction for Children ofEthnic Minorities in South Wales" (Graham Howells); (7) "Cooperative Learning in the Workshop: Integrating Social Skills, GroupRoles and Processing to Facilitate Learning in the Integrated Language Arts Classroom" (Carol A. -

Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru the National Assembly for Wales

Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru The National Assembly for Wales Y Pwyllgor Materion Cyfansoddiadol a Deddfwriaethol The Constitutional and Legislative Affairs Committee Dydd Llun, 11 Mawrth 2013 Monday, 11 March 2013 Cynnwys Contents Cyflwyniad, Ymddiheuriadau, Dirprwyon a Datganiadau o Fuddiant Introduction, Apologies, Substitutions and Declarations of Interest Offerynnau Nad Ydynt yn Cynnwys Unrhyw Faterion i’w Codi o dan Reolau Sefydlog Rhif 21.2 neu 21.3 Instruments that Raise no Reporting Issues under Standing Order Nos. 21.2 or 21.3 Offerynnau sy’n Cynnwys Materion i Gyflwyno Adroddiad arnynt i’r Cynulliad o dan Reolau Sefydlog Rhif 21.2 neu 21.3 Instruments that Raise Issues to be Reported to the Assembly under Standing Order Nos. 21.2 or 21.3 Cynnig o dan Reol Sefydlog Rhif 17.42 i Benderfynu Gwahardd y Cyhoedd o’r Cyfarfod Motion under Standing Order No. 17.42 to Resolve to Exclude the Public from the Meeting Tystiolaeth Ynghylch yr Ymchwiliad i Ddeddfu a’r Eglwys yng Nghymru Evidence in Relation to the Inquiry on Law Making and the Church in Wales Papurau i’w Nodi Papers to Note Cynnig o dan Reol Sefydlog Rhif 17.42(vi) i Benderfynu Gwahardd y Cyhoedd o’r Cyfarfod 11/03/2013 Motion under Standing Order No. 17.42(vi) to Resolve to Exclude the Public from the Meeting Cofnodir y trafodion yn yr iaith y llefarwyd hwy ynddi yn y pwyllgor. Yn ogystal, cynhwysir trawsgrifiad o’r cyfieithu ar y pryd. The proceedings are reported in the language in which they were spoken in the committee. -

Welsh Church

(S.R. 0-- O. and S.I. Revised to December 31,1948) ---------~ ~--"------- WELSH CHURCH 1. Charter of Incorporation. 2. Burial Grounds (Commencemen~ 1 of Enactment). p. 220. 1. Charter of Incorporation ORDER IN COUNCIl, APPROVING DRAFT CHARTER UNDER SECTION 13 (2) OF THE WELSH CHURCH ACT, 1914 (4 & 5 GEO. 5. c. 91) INCORPORATING THE REPRESENTA TIVE BODY OF THE CHURCH IN WALES. 1919 No. 564 At the Court at Buckingham Palace, the 15th day of April, 1919. PRESENT, The King's Most Excellent Majesty in Gouncil. :\Vhereas there was this day read at the Board a Report of a Cmnmittee of the Lord.. of His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy C.ouncil, dated the 9th day of April, 1919, in the words following, VIZ.:- " Your Majesty having been pleased, by Your Order of the 10th day of February, 1919, to refer unto this Committee the humble Petition of The Right Reverend the Lord Bishop of St. Asaph, The Right Reverend the Lord Bishop of St. David's, 'rhe Right Reverend the Lord Bishop of Bangor, The Right Reverend the Lord Bishop of Llandaff, The Right Honourable Sir John Eldon Bankes, The Right Honourable Sir J ames Richard Atkin, Sir Owen Philipps, G.C.M.G., M.P., and The Honourable Sir John Sankey, G.B.E., praying that Your Majesty would be pleased, in exercise of Your Royal Preroga- 1,ive and of the power in that behalf contained in Section 13 (2) of the Welsh Church Act, 1914, to grant a Charter of Incorpora tion to the persons mentioned in the Second Schedule to the said Petition, and their successors, being the Representative Body of the Church in Wales under the provisions of the said Ad: "1'he Lords of the Committee, in obedience to Your Majesty's said Order of Reference, have taken the said Petition into consideration, and do this day agree humbly to report, as their opinion, to Your Majesty, that a Charter may be grant~~ by Your Majesty in terms of the Draft hereunto annexed. -

Report on the Welsh Language

Index Abse, Leo, 193 Coalitionism, 157 Annan, Lord, Olairman of the Commit- Committee on Scottish Affairs, 56 tee on Broadcasting 1974, 76 Commonwealth Office, 60 Army, British, 120 Congested Districts Board for the High Arson, 1979-80 campaign in Wales, 89 lands 1897, 150 Assembly, 4 Conservatism and Unionism, 139-70 Scottish, 187, 188, 189, 191, 192 political ideas and practice, 143-4 Welsh, 96, 187, 191, 192, 194 territorial politics, 143 Conservative Irish policy, 153 Balfour, A. J., 153, 155, 157 Conservative Party, 139-70 passim 'Barnett formula', 21, 24 in Scotland and Wales, 14-16 Bi-lingualism in Wales, 69. 70, 75, 78, and voting, 227-47 88 in Wales, 73 bi-lingual education, 83, 87 and Welsh language, 93-4 schools, 81, 82 Constitution, Royal Commission on 'BloodySunday',30January 1972,114 (Crowther, Kilbrandon), 3-4, 13, Board of Trade, 36, 37, 45, 50 16, 94, 188-9, 191 Boer War, 148, 154, 156 Constitutional Convention (NI) 1975, Bonar Law, 157 117' 126 Border Poll Act 1973, 122 CoS IRA, 42, 53 Boundaries between Northern Ireland Council for Wales and Monmouthshire, and Irish Republic, 123 report on The Welsh Language Bowen Committee 1973, 71, 94 Today 1963, 72 British Leyland, 19, 42, 48, 51, 53 Council for the Welsh Language, 72, 92, 94,95 Cabinet and ministries, 60 Council of Ireland, 116, ll7, 124 Callaghan, James, 17, Ill, ll2, 113, Crossman, Richard, 17, 18, 191 127 Diary 1976, 14 Campaign for Democracy in Ulster, Ill Crown, the, 1-3, 100, 101, 102, 104, Campbell-Bannerman, Sir H., 155 119 Carmarthen by-election 1966, 183 Crowther-Hunt, Lord, 191 Central Policy Review Staff Report, 27 Olamberlain, Neville, 148, 159, 161 Dalyell, Tam, 194. -

Welsh Disestablishment: 'A Blessing in Disguise'

Welsh disestablishment: ‘A blessing in disguise’. David W. Jones The history of the protracted campaign to achieve Welsh disestablishment was to be characterised by a litany of broken pledges and frustrated attempts. It was also an exemplar of the ‘democratic deficit’ which has haunted Welsh politics. As Sir Henry Lewis1 declared in 1914: ‘The demand for disestablishment is a symptom of the times. It is the democracy that asks for it, not the Nonconformists. The demand is national, not denominational’.2 The Welsh Church Act in 1914 represented the outcome of the final, desperate scramble to cross the legislative line, oozing political compromise and equivocation in its wake. Even then, it would not have taken place without the fortuitous occurrence of constitutional change created by the Parliament Act 1911. This removed the obstacle of veto by the House of Lords, but still allowed for statutory delay. Lord Rosebery, the prime minister, had warned a Liberal meeting in Cardiff in 1895 that the Welsh demand for disestablishment faced a harsh democratic reality, in that: ‘it is hard for the representatives of the other 37 millions of population which are comprised in the United Kingdom to give first and the foremost place to a measure which affects only a million and a half’.3 But in case his audience were insufficiently disheartened by his homily, he added that there was: ‘another and more permanent barrier which opposes itself to your wishes in respect to Welsh Disestablishment’, being the intransigence of the House of Lords.4 The legislative delay which the Lords could invoke meant that the Welsh Church Bill was introduced to parliament on 23 April 1912, but it was not to be enacted until 18 September 1914. -

THE USE of INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES in PROCEEDINGS of the HOUSE of COMMONS and COMMITTEES Report of the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs

THE USE OF INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES IN PROCEEDINGS OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS AND COMMITTEES Report of the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs The Honourable Larry Bagnell, Chair JUNE 2018 42nd PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION Published under the authority of the Speaker of the House of Commons SPEAKER’S PERMISSION The proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees are hereby made available to provide greater public access. The parliamentary privilege of the House of Commons to control the publication and broadcast of the proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees is nonetheless reserved. All copyrights therein are also reserved. Reproduction of the proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees, in whole or in part and in any medium, is hereby permitted provided that the reproduction is accurate and is not presented as official. This permission does not extend to reproduction, distribution or use for commercial purpose of financial gain. Reproduction or use outside this permission or without authorization may be treated as copyright infringement in accordance with the Copyright Act. Authorization may be obtained on written application to the Office of the Speaker of the House of Commons. Reproduction in accordance with this permission does not constitute publication under the authority of the House of Commons. The absolute privilege that applies to the proceedings of the House of Commons does not extend to these permitted reproductions. Where a reproduction includes briefs to a Standing Committee of the House of Commons, authorization for reproduction may be required from the authors in accordance with the Copyright Act. -

Parliamentary Debates House of Commons Official Report

PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT Welsh Grand Committee SILK COMMISSION Wednesday 5 February 2014 (Morning) CONTENTS Silk Commission General debate in progress when the Committee adjourned till this day at Two o’clock. PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS LONDON – THE STATIONERY OFFICE LIMITED £6·00 Members who wish to have copies of the Official Report of Proceedings in General Committees sent to them are requested to give notice to that effect at the Vote Office. No proofs can be supplied. Corrigenda slips may be published with Bound Volume editions. Corrigenda that Members suggest should be clearly marked in a copy of the report—not telephoned—and must be received in the Editor’s Room, House of Commons, not later than Sunday 9 February 2014 STRICT ADHERENCE TO THIS ARRANGEMENT WILL GREATLY FACILITATE THE PROMPT PUBLICATION OF THE BOUND VOLUMES OF PROCEEDINGS IN GENERAL COMMITTEES © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2014 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 1 Welsh Grand Committee5 FEBRUARY 2014 Silk Commission 2 The Committee consisted of the following Members: Chairs: MARTIN CATON,†ALBERT OWEN † Bebb, Guto (Aberconwy) (Con) Irranca-Davies, Huw (Ogmore) (Lab) Brennan, Kevin (Cardiff West) (Lab) † James, Mrs Siân C. (Swansea East) (Lab) Bryant, Chris (Rhondda) (Lab) † Jones, Mr David (Secretary of State for Wales) Buckland, Mr Robert (South Swindon) (Con) Jones, Susan Elan (Clwyd South) (Lab) † Cairns, Alun (Vale of Glamorgan) (Con) † Kawczynski, Daniel (Shrewsbury and Atcham) Clwyd, Ann (Cynon Valley) (Lab) (Con) † Crabb, Stephen (Parliamentary Under-Secretary of † Llwyd, Mr Elfyn (Dwyfor Meirionnydd) (PC) State for Wales) † Lucas, Ian (Wrexham) (Lab) David, Wayne (Caerphilly) (Lab) Moon, Mrs Madeleine (Bridgend) (Lab) Davies, David T. -

Church Autonomy in the United Kingdom

Final Draft - 12 March 1999 CHURCH AUTONOMY IN THE UNITED KINGDOM MARK HILL LLB, LLM(Canon Law), AKC, of the Middle Temple, Barrister-at-Law; Research Fellow, Centre for Law and Religion, Cardiff Law School; Formerly Visiting Fellow, Emmanuel College, Cambridge; Deputy Chancellor of the Diocese of Winchester Presented to the Second European/American Conference on Religious Freedom, ‘Church Autonomy and Religious Liberty’, at the University of Trier, Germany, on 27-30 May 1999 From the point of view of the state, though not necessarily of every religious organisation, the autonomy of churches in any legal system is achieved actively, through the express grant and preservation of rights of self-determination, self-governance and self-regulation; and passively, through non-interference on the part of organs of state such as national government, local or regional government or the secular courts. In the United Kingdom there is no systematic provision made for the autonomy of churches and, in the main, a self-denying ordinance of neutrality predominates. This paper considers, by reference to the general and the particular, the operation of churches within the United Kingdom1 and the extent to which the state does – and does not – interfere with their internal regulation. The Human Rights Act 1998 Though the first nation state of the Council of Europe to ratify the European Convention on Human Rights on 18 March 1951, and though permitting individual petition to the European Court in Strasbourg since 1966,2 the United Kingdom declined to give effect to the Convention in its domestic law until the socialist government recently passed the Human Rights Act 1998. -

The Cabinet Manual

The Cabinet Manual A guide to laws, conventions and rules on the operation of government 1st edition October 2011 The Cabinet Manual A guide to laws, conventions and rules on the operation of government 1st edition October 2011 Foreword by the Prime Minister On entering government I set out, Cabinet has endorsed the Cabinet Manual as an authoritative guide for ministers and officials, with the Deputy Prime Minister, our and I expect everyone working in government to shared desire for a political system be mindful of the guidance it contains. that is looked at with admiration This country has a rich constitution developed around the world and is more through history and practice, and the Cabinet transparent and accountable. Manual is invaluable in recording this and in ensuring that the workings of government are The Cabinet Manual sets out the internal rules far more open and accountable. and procedures under which the Government operates. For the first time the conventions determining how the Government operates are transparently set out in one place. Codifying and publishing these sheds welcome light on how the Government interacts with the other parts of our democratic system. We are currently in the first coalition Government David Cameron for over 60 years. The manual sets out the laws, Prime Minister conventions and rules that do not change from one administration to the next but also how the current coalition Government operates and recent changes to legislation such as the establishment of fixed-term Parliaments. The content of the Cabinet Manual is not party political – it is a record of fact, and I welcome the role that the previous government, select committees and constitutional experts have played in developing it in draft to final publication. -

WRITTEN EVIDENCE from the SECRETARY of STATE for WALES I Shall Address in Turn Each of the Issues Raised in the Committee’S Call for Evidence

Subordinate Legislation Committee Inquiry into the scrutiny of subordinate legislation and delegated powers Consultation Response SLC 9 - Secretary of State for Wales WRITTEN EVIDENCE FROM THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WALES I shall address in turn each of the issues raised in the Committee’s call for evidence 1. Scrutiny of Statutory Instruments on the grounds set out in Standing Order 15.3 • The effectiveness of the Welsh Assembly Government’s consultation with stakeholders in respect of statutory instruments: For the Welsh Assembly Government to comment. • How the Welsh Assembly Government works with the UK Government when drafting statutory instruments For the Welsh Assembly Government to comment. However, UK Departments and the Welsh Assembly Government work closely together where legislation requires drafting of a statutory instrument, to ensure that Welsh interests are properly represented. • How the Committee can undertake effective and timely scrutiny of regulations in respect of their legal importance or policy objectives This is a matter for the Committee. • What the Committee can learn from the House of Lords Merits Committee, whose reporting remit is similar to that of SO 15.3 This is a matter for the Committee. 2. Additional considerations relating to statutory instruments implementing European Union Directives • The effectiveness and transparency of the Welsh Assembly Government’s transposition procedures For the Welsh Assembly Government to comment. • The extent to which the Welsh Assembly Government can and does tailor the implementing regulations to the needs of Wales in view of the parameters set by European Directives For the Welsh Assembly Government to comment. 3. Scrutiny of Bills of the UK Parliament which have an impact in Wales • The procedures in place to make transparent the implications of UK Bills on areas of devolved competency and the powers of Welsh Ministers As Secretary of State for Wales, I have statutory duty {section 33 of GOWA 06} to consult the National Assembly on the UK Government’s legislative programme. -

The Pre-Action Protocol for Judicial Review Under the Civil Procedure Rules

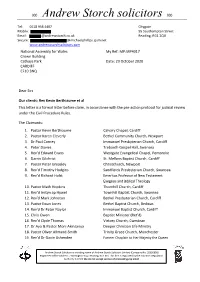

000 Andrew Storch solicitors 000 Tel: 0118 958 4407 Citygate Mobile: 95 Southampton Street Email: @andrewstorch.co.uk Reading, RG1 2QU Secure: @michaelphillips.cjsm.net www.andrewstorchsolicitors.com National Assembly for Wales My Ref: MP:MP4017 Crown Building Cathays Park Date: 23 October 2020 CARDIFF CF10 3NQ Dear Sirs Our clients: Rev Kevin Berthiaume et al This letter is a formal letter before claim, in accordance with the pre-action protocol for judicial review under the Civil Procedure Rules. The Claimants: 1. Pastor Kevin Berthiaume Calvary Chapel, Cardiff 2. Pastor Karen Cleverly Bethel Community Church, Newport 3. Dr Paul Corney Immanuel Presbyterian Church, Cardiff 4. Peter Davies Treboeth Gospel Hall, Swansea 5. Rev’d Edward Evans Westgate Evangelical Chapel, Pembroke 6. Darrin Gilchrist St. Mellons Baptist Church, Cardiff 7. Pastor Peter Greasley Christchurch, Newport 8. Rev’d Timothy Hodgins Sandfields Presbyterian Church, Swansea 9. Rev’d Richard Holst Emeritus Professor of New Testament Exegesis and Biblical Theology 10. Pastor Math Hopkins Thornhill Church, Cardiff 11. Rev’d Iestyn ap Hywel Townhill Baptist Church, Swansea 12. Rev'd Mark Johnston Bethel Presbyterian Church, Cardiff 13. Pastor Ewan Jones Bethel Baptist Church, Bedwas 14. Rev'd Dr Peter Naylor Immanuel Baptist Church, Cardiff 15. Chris Owen Baptist Minister (Ret’d) 16. Rev’d Clyde Thomas Victory Church, Cwmbran 17. Dr Ayo & Pastor Moni Akinsanya Deeper Christian Life Minstry 18. Pastor Oliver Allmand-Smith Trinity Grace Church, Manchester 19. Rev’d Dr Gavin Ashenden Former Chaplain to Her Majesty the Queen Andrew Storch Solicitors is a trading name of Andrew Storch Solicitors Limited (Company No. -

Church and State in the Twenty-First Century

THIRTY-SECOND ANNUAL CONFERENCE 5 to 7 April 2019 Cumberland Lodge, Windsor Great Park Church and State in the Twenty-first Century Slide 7 Table of contents Welcome and Introduction 3 Conference programme 4-6 Speakers' biographies 7-10 Abstracts 11-14 Past and future Conferences 15 Attendance list 16-18 AGM Agenda 19-20 AGM Minutes of previous meeting 21-23 AGM Chairman’s Report 24-27 AGM Accounts 2017/18 28-30 Committee membership 31 Upcoming events 32 Day Conference 2020 33 Cumberland Lodge 34-36 Plans of Cumberland Lodge 37-39 Directions for the Royal Chapel of All Saints 40 2 Welcome and Introduction We are very pleased to welcome you to our Residential Conference at Cumberland Lodge. Some details about Cumberland Lodge appear at the end of this booklet. The Conference is promoting a public discussion of the nature of establishment and the challenges it may face in the years ahead, both from a constitutional vantage point and in parochial ministry for the national church. A stellar collection of experts has been brought together for a unique conference which will seek to re-imagine the national church and public religion in the increasingly secular world in the current second Elizabethan age and hereafter. Robert Blackburn will deliver a keynote lecture on constitutional issues of monarchy, parliament and the Church of England. Norman Doe and Colin Podmore will assess the centenaries of, respectively, the Welsh Church Act 1914 and the Church of England Assembly (Powers) Act 1919 (known as the ‘Enabling Act’), and the experience of English and Welsh Anglicanism over this period.