Jerusalem on the Map Basic Facts and Trends 1967-1996 Maya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jerusalem Chronology 2015 January Jan. 1: the Israeli Supreme Court

Jerusalem Chronology 2015 January Jan. 1: The Israeli Supreme Court rejects an appeal to prevent the demolition of the homes of four Palestinians from East Jerusalem who attacked Israelis in West Jerusalem in recent months. - Marabouts at Al-Aqsa Mosque confront a group of settlers touring Al-Aqsa compound. Jan. 3: Palestinian MK Ahmad Tibi joins hundreds of Palestinians marching toward the Al-Aqsa Mosque in the Old City of Jerusalem to mark the Prophet Muhammad's birthday. Jan. 5: Settlers tour Al-Aqsa Mosque compound while Israeli forces confiscate the IDs of Muslims trying to enter. - Around 50 Israeli forces along with 18 settlers tour Al-Aqsa compound. Jan. 8: A Jewish Israeli man is stabbed and injured by an unknown assailant while walking near the Old City’s Damascus Gate. Jan. 9: Israeli police detain at least seven Palestinians in a series of raids in the Old City over the stabbing a day earlier. - Yedioth Ahronoth reports that the Israeli Intelligence (Shabak) frustrated an operation that was intended to blow the Dome of the Rock by an American immigrant. Jan. 11: Israeli police forces detain seven Palestinians from Silwan after a settler vehicle was torched in the area. Jan. 12: A Jerusalem magistrate court has ruled that Israeli settlers who occupied Palestinian homes in East Jerusalem may not make substantial changes to the properties. - Settlers tour Al-Aqsa Mosque compound. Jan. 13: Israeli forces detained three 14-year old youth during a raid on Issawiyya and two women while leaving Al-Aqsa Mosque. Jan. 14: Jewish extremists morning punctured the tires of 11 vehicles in Beit Safafa. -

BULLETIN - JANUARY, 2012 Bulletin Electric Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated Vol

The ERA BULLETIN - JANUARY, 2012 Bulletin Electric Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated Vol. 55, No. 1 January, 2012 The Bulletin WELCOME TO OUR NEW READERS Published by the Electric Railroaders’ Association, For many of you, this is the first time that ing month. This month’s issue includes re- Incorporated, PO Box you are receiving The Bulletin. It is not a ports on transit systems across the nation. In 3323, New York, New new publication, but has been produced by its 53-year history there have been just three York 10163-3323. the New York Division of the Electric Rail- Editors: Henry T. Raudenbush (1958-9), Ar- roaders’ Association since May, 1958. Over thur Lonto (1960-81) and Bernie Linder For general inquiries, the years we have expanded the scope of (1981-present). The current staff also in- contact us at bulletin@ coverage from the metropolitan New York cludes News Editor Randy Glucksman, Con- erausa.org or by phone area to the nation and the world, and mem- tributing Editor Jeffrey Erlitz, and our Produc- at (212) 986-4482 (voice ber contributions are always welcomed in this tion Manager, David Ross, who puts the mail available). ERA’s website is effort. The first issue foretold the abandon- whole publication together. We hope that you www.erausa.org. ment of the Polo Grounds Shuttle the follow- will enjoy reading The Bulletin Editorial Staff: Editor-in-Chief: Bernard Linder THIRD AVENUE’S POOR FINANCIAL CONDITION LED News Editor: Randy Glucksman TO ITS CAR REBUILDING PROGRAM 75 YEARS AGO Contributing Editor: Jeffrey Erlitz This company, which was founded in 1853, the equipment was in excellent condition and was able to survive longer than any other was well-maintained. -

Jerusalem: City of Dreams, City of Sorrows

1 JERUSALEM: CITY OF DREAMS, CITY OF SORROWS More than ever before, urban historians tell us that global cities tend to look very much alike. For U.S. students. the“ look alike” perspective makes it more difficult to empathize with and to understand cultures and societies other than their own. The admittedly superficial similarities of global cities with U.S. ones leads to misunderstandings and confusion. The multiplicity of cybercafés, high-rise buildings, bars and discothèques, international hotels, restaurants, and boutique retailers in shopping malls and multiplex cinemas gives these global cities the appearances of familiarity. The ubiquity of schools, university campuses, signs, streetlights, and urban transportation systems can only add to an outsider’s “cultural and social blindness.” Prevailing U.S. learning goals that underscore American values of individualism, self-confidence, and material comfort are, more often than not, obstacles for any quick study or understanding of world cultures and societies by visiting U.S. student and faculty.1 Therefore, international educators need to look for and find ways in which their students are able to look beyond the veneer of the modern global city through careful program planning and learning strategies that seek to affect the students in their “reading and learning” about these fertile centers of liberal learning. As the students become acquainted with the streets, neighborhoods, and urban centers of their global city, their understanding of its ways and habits is embellished and enriched by the walls, neighborhoods, institutions, and archaeological sites that might otherwise cause them their “cultural and social blindness.” Jerusalem is more than an intriguing global historical city. -

4.Employment Education Hebrew Arnona Culture and Leisure

Did you know? Jerusalem has... STARTUPS OVER OPERATING IN THE CITY OVER SITES AND 500 SYNAGOGUES 1200 39 MUSEUMS ALTITUDE OF 630M CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS COMMUNITY 51 AND ARTS CENTERS 27 MANAGERS ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem JERUSALEM IS ISRAEL’S STUDENTS LARGEST CITY 126,000 DUNAM Graphic design by OVER 40,000 STUDYING IN THE CITY 50,000 VOLUNTEERS Illustration by www.rinatgilboa.com • Learning centers are available throughout the city at the local Provide assistance for olim to help facilitate a smooth absorption facilities. The centers offer enrichment and study and successful integration into Jerusalem. programs for school age children. • Jerusalem offers a large selection of public and private schools Pre - Aliyah Services 2 within a broad religious spectrum. Also available are a broad range of learning methods offered by specialized schools. Assistance in registration for municipal educational frameworks. Special in Jerusalem! Assistance in finding residence, and organizing community needs. • Tuition subsidies for Olim who come to study in higher education and 16 Community Absorption Coordinators fit certain criteria. Work as a part of the community administrations throughout the • Jerusalem is home to more than 30 institutions of higher education city; these coordinators offer services in educational, cultural, sports, that are recognized by the Student Authority of the Ministry of administrative and social needs for Olim at the various community Immigration & Absorption. Among these schools is Hebrew University – centers. -

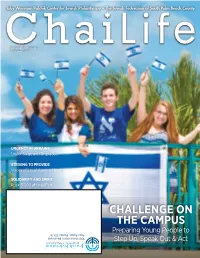

Challenge on the Campus

Volume 10 • Issue 3 Summer 2015 URGENCY IN UKRAINE Under Siege and Displaced STRIVING TO PROVIDE Voices of Local Agency Heads SOLIDARITY AND SPIRIT Rock 3,000 at IsraelFest CHALLENGE ON THE CAMPUS Boca Raton, Florida 33428 Florida Raton, Boca Preparing Young People to 9901 Donna Klein Boulevard Klein Donna 9901 Step Up, Speak Out & Act 1 CHAILIFE We’re Saving you a Seat! JOIN US FOR OUR COMMUNITY MISSION TO ISRAEL! PASSENGER B OA R D I N G your naMe here PASS DATE NOVEMBER 13-19, 2015 DATE 11.13.15 - 11.19.15 DEPARTURE USA ARRIVAL TEL AVIV, ISRAEL MISSION CHAIRS KAREN & MARK DERN ADELE & HERMAN LEBERSFELD See the Innovation Nation Enjoy food, wine and culture Meet with security experts Experience outdoor adventures Attend sessions with Celebrate Shabbat in Jerusalem and more! government officials jewishboca.org/spirit For more information, contact Barbara Kabatznik at 561.852.6050 or [email protected]. PRICE: $3,200* per person – land only, double occupancy *$500 subsidy per person available A minimum individual gift of $500 to the 2016 UJA/Jewish Federation of South Palm Beach County Annual Campaign is required to attend. C atCh the Spirit! We’re Saving 6 JOIN US FOR OURyou COMMUNITY MISSIONa STO ISRAEL!eat! 8 PASSENGER B OA R D I N G your naMe here PASS 16 DATE NOVEMBER 13-19, 2015 DATE 11.13.15 - 11.19.15 DEPARTURE USA 36 ARRIVAL TEL AVIV, ISRAEL MISSION CHAIRS KAREN & MARK DERN ADELE & HERMAN LEBERSFELD 44 FEATURES 4 AN URGENT CALL See the Innovation Nation Enjoy food, wine and culture Ukraine in Need Meet with security experts Experience outdoor adventures 6 JOURNEY TO IMPACT Attend sessions with Celebrate Shabbat in Jerusalem and more! Our 2015 Annual Meeting government officials 8 IN SOLIDarity AND SPIRIT CONTENTS IsraelFest 2015 14 THEY STRIVE to PROVIDE Voices of Agency Heads 14 Federation Partnerships 20 Campaign 2015 jewishboca.org/spirit 16 COMMUNITY OF unity For Naftali, Gil-Ad & Eyal 26 Men’s Division For more information, contact Barbara Kabatznik at 561.852.6050 or [email protected]. -

Kinder Torah Will Ð"Ìá Bidden to Work the Land?” Jewish People

KIINNDDEERR TOORRAAHH © K P A R A S H A S BTE H A R were like heavenly angels. Their strength SHMITTA was unfathomable. How can it be that a THE HOLY LAND person can achieve such great things from “Y aakov, may I water our garden the mitzvah of Shmitta?” “H ashem spoke to Moshe on Har during the Shmitta year?” “Let’s think about this a minute, Avi. Let Sinai saying, ‘…the land shall rest for “Yes Rachel. We live here in Eretz Yisrael us try to imagine ourselves back in the Hashem’” (Vayikra 25:1-2). Rashi asks the and we are observing the Shmitta. There- days of the Beis HaMikdash.” famous question, “How is Shmitta (the fore, you may water it enough to keep And so, Chaim begins to tell a story. Sabbatical year) related to Har Sinai?” the grass alive.” “Abba, thank you so much for taking such The Keli Yakar has a novel answer to this “How do I know how much water it good care of us. Boruch Hashem, we question. Shmitta and Har Sinai are simi- needs to stay alive?” have a nice farm, and every day you go lar in many ways. Moshe Rabbeinu went “Experiment and see. If you see it drying out and work the fields. You plow, plant, up to Har Sinai after counting seven out too much, then water it.” weeks (49 days) from Yetzias Mitzraim. and tend to the crops. When they are “That may not be so easy.” fully grown, you pick them and bring So too, Shmitta is once every seven years, “Do your best, Rachel dear, and Hashem them to Imma to cook into the delicious and Yovel is after seven Shmittas (49 will help.” meals that we eat. -

Retail Prices in a City*

Retail Prices in a City Alon Eizenberg Saul Lach The Hebrew University and CEPR The Hebrew University and CEPR Merav Yiftach Israel Central Bureau of Statistics July 2017 Abstract We study grocery price differentials across neighborhoods in a large metropolitan area (the city of Jerusalem, Israel). Prices in commercial areas are persistently lower than in residential neighborhoods. We also observe substantial price variation within residential neighborhoods: retailers that operate in peripheral, non-a uent neighborhoods charge some of the highest prices in the city. Using CPI data on prices and neighborhood-level credit card data on expenditure patterns, we estimate a model in which households choose where to shop and how many units of a composite good to purchase. The data and the estimates are consistent with very strong spatial segmentation. Combined with a pricing equation, the demand estimates are used to simulate interventions aimed at reducing the cost of grocery shopping. We calculate the impact on the prices charged in each neighborhood and on the expected price paid by its residents - a weighted average of the prices paid at each destination, with the weights being the probabilities of shopping at each destination. Focusing on prices alone provides an incomplete picture and may even be misleading because shopping patterns change considerably. Specifically, we find that interventions that make the commercial areas more attractive and accessible yield only minor price reductions, yet expected prices decrease in a pronounced fashion. The benefits are particularly strong for residents of the peripheral, non-a uent neighborhoods. We thank Eyal Meharian and Irit Mishali for their invaluable help with collecting the price data and with the provision of the geographic (distance) data. -

מכון ירושלים לחקר ישראל Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies שנתון

מכון ירושלים לחקר ישראל Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies שנתון סטטיסטי לירושלים Statistical Yearbook of Jerusalem 2016 2016 לוחות נוספים – אינטרנט Additional Tables - Internet לוח ג/19 - אוכלוסיית ירושלים לפי קבוצת אוכלוסייה, רמת הומוגניות חרדית1, רובע, תת-רובע ואזור סטטיסטי, 2014 Table III/19 - Population of Jerusalem by Population Group, Ultra-Orthodox Homogeneity Level1, Quarter, Sub-Quarter, and Statistical Area, 2014 % רמת הומוגניות חרדית )1-12( סך הכל יהודים ואחרים אזור סטטיסטי ערבים Statistical area Ultra-Orthodox Jews and Total homogeneity Arabs others level )1-12( ירושלים - סך הכל Jerusalem - Total 10 37 63 849,780 רובע Quarter 1 10 2 98 61,910 1 תת רובע 011 - נווה יעקב Sub-quarter 011 - 3 1 99 21,260 Neve Ya'akov א"ס .S.A 0111 נווה יעקב )מזרח( Neve Ya'akov (east) 1 0 100 2,940 0112 נווה יעקב - Neve Ya'akov - 1 0 100 2,860 קרית קמניץ Kiryat Kamenetz 0113 נווה יעקב )דרום( - Neve Ya'akov (south) - 6 1 99 3,710 רח' הרב פניז'ל, ,.Harav Fenigel St מתנ"ס community center 0114 נווה יעקב )מרכז( - Neve Ya'akov (center) - 6 1 99 3,450 מבוא אדמונד פלג .Edmond Fleg St 0115 נווה יעקב )צפון( - 3,480 99 1 6 Neve Ya'akov (north) - Meir Balaban St. רח' מאיר בלבן 0116 נווה יעקב )מערב( - 4,820 97 3 9 Neve Ya'akov (west) - Abba Ahimeir St., רח' אבא אחימאיר, Moshe Sneh St. רח' משה סנה תת רובע 012 - פסגת זאב צפון Sub-quarter 012 - - 4 96 18,500 Pisgat Ze'ev north א"ס .S.A 0121 פסגת זאב צפון )מערב( Pisgat Ze'ev north (west) - 6 94 4,770 0122 פסגת זאב צפון )מזרח( - Pisgat Ze'ev north (east) - - 1 99 3,120 רח' נתיב המזלות .Netiv Hamazalot St 0123 -

The Upper Kidron Valley

Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Founded by the Charles H. Revson Foundation The Upper Kidron Valley Conservation and Development in the Visual Basin of the Old City of Jerusalem Editor: Israel Kimhi Jerusalem 2010 Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies – Study No. 398 The Upper Kidron Valley Conservation and Development in the Visual Basin of the Old City of Jerusalem Editor: Israel Kimhi This publication was made possible thanks to the assistance of the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Fund, San Francisco. 7KHFRQWHQWRIWKLVGRFXPHQWUHÀHFWVWKHDXWKRUV¶RSLQLRQRQO\ Photographs: Maya Choshen, Israel Kimhi, and Flash 90 Linguistic editing (Hebrew): Shlomo Arad Production and printing: Hamutal Appel Pagination and design: Esti Boehm Translation: Sagir International Translations Ltd. © 2010, The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Hay Elyachar House 20 Radak St., Jerusalem 92186 http://www.jiis.org E-mail: [email protected] Research Team Israel Kimhi – head of the team and editor of the report Eran Avni – infrastructures, public participation, tourism sites Amir Eidelman – geology Yair Assaf-Shapira – research, mapping, and geographical information systems Malka Greenberg-Raanan – physical planning, development of construction Maya Choshen – population and society Mike Turner – physical planning, development of construction, visual analysis, future development trends Muhamad Nakhal ±UHVLGHQWSDUWLFLSDWLRQKLVWRU\SUR¿OHRIWKH$UDEQHLJKERU- hoods Michal Korach – population and society Israel Kimhi – recommendations for future development, land uses, transport, planning Amnon Ramon – history, religions, sites for conservation Acknowledgments The research team thanks the residents of the Upper Kidron Valley and the Visual Basin of the Old City, and their representatives, for cooperating with the researchers during the course of the study and for their willingness to meet frequently with the team. -

A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org APRIL 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Map .................................................................................................................................. i Summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 Definitions of Apartheid and Persecution ................................................................................. -

Greater Jerusalem” Has Jerusalem (Including the 1967 Rehavia Occupied and Annexed East Jerusalem) As Its Centre

4 B?63 B?466 ! np ! 4 B?43 m D"D" np Migron Beituniya B?457 Modi'in Bei!r Im'in Beit Sira IsraelRei'ut-proclaimed “GKharbrathae al Miasbah ter JerusaBeitl 'Uer al Famuqa ” D" Kochav Ya'akov West 'Ein as Sultan Mitzpe Danny Maccabim D" Kochav Ya'akov np Ma'ale Mikhmas A System of Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Deir Quruntul Kochav Ya'akov East ! Kafr 'Aqab Kh. Bwerah Mikhmas ! Beit Horon Duyuk at Tahta B?443 'Ein ad D" Rafat Jericho 'Ajanjul ya At Tira np ya ! Beit Liq Qalandi Kochav Ya'akov South ! Lebanon Neve Erez ¥ ! Qalandiya Giv'at Ze'ev D" a i r Jaba' y 60 Beit Duqqu Al Judeira 60 B? a S Beit Nuba D" B? e Atarot Ind. Zone S Ar Ram Ma'ale Hagit Bir Nabala Geva Binyamin n Al Jib a Beit Nuba Beit 'Anan e ! Giv'on Hahadasha n a r Mevo Horon r Beit Ijza e t B?4 i 3 Dahiyat al Bareed np 6 Jaber d Aqbat e Neve Ya'akov 4 M Yalu B?2 Nitaf 4 !< ! ! Kharayib Umm al Lahim Qatanna Hizma Al Qubeiba ! An Nabi Samwil Ein Prat Biddu el Almon Har Shmu !< Beit Hanina al Balad Kfar Adummim ! Beit Hanina D" 436 Vered Jericho Nataf B? 20 B? gat Ze'ev D" Dayr! Ayyub Pis A 4 1 Tra Beit Surik B?37 !< in Beit Tuul dar ! Har A JLR Beit Iksa Mizpe Jericho !< kfar Adummim !< 21 Ma'ale HaHamisha B? 'Anata !< !< Jordan Shu'fat !< !< A1 Train Ramat Shlomo np Ramot Allon D" Shu'fat !< !< Neve Ilan E1 !< Egypt Abu Ghosh !< B?1 French Hill Mishor Adumim ! B?1 Beit Naqquba !< !< !< ! Beit Nekofa Mevaseret Zion Ramat Eshkol 1 Israeli Police HQ Mesilat Zion B? Al 'Isawiya Lifta a Qulunyia ! Ma'alot Dafna Sho'eva ! !< Motza Sheikh Jarrah !< Motza Illit Mishor Adummim Ind. -

Religion and Geography

Park, C. (2004) Religion and geography. Chapter 17 in Hinnells, J. (ed) Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion. London: Routledge RELIGION AND GEOGRAPHY Chris Park Lancaster University INTRODUCTION At first sight religion and geography have little in common with one another. Most people interested in the study of religion have little interest in the study of geography, and vice versa. So why include this chapter? The main reason is that some of the many interesting questions about how religion develops, spreads and impacts on people's lives are rooted in geographical factors (what happens where), and they can be studied from a geographical perspective. That few geographers have seized this challenge is puzzling, but it should not detract us from exploring some of the important themes. The central focus of this chapter is on space, place and location - where things happen, and why they happen there. The choice of what material to include and what to leave out, given the space available, is not an easy one. It has been guided mainly by the decision to illustrate the types of studies geographers have engaged in, particularly those which look at spatial patterns and distributions of religion, and at how these change through time. The real value of most geographical studies of religion in is describing spatial patterns, partly because these are often interesting in their own right but also because patterns often suggest processes and causes. Definitions It is important, at the outset, to try and define the two main terms we are using - geography and religion. What do we mean by 'geography'? Many different definitions have been offered in the past, but it will suit our purpose here to simply define geography as "the study of space and place, and of movements between places".