BOB SEDERGREEN: the INTERVIEW by Adrian Jackson*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Highly Recommended New Cds for 2018

Ed Love's Highly Recommended New CDs for 2018 Artist Title Label Dave Young and Terry Promane Octet Volume Two Modica Music Phil Parisot Creekside OA2 John Stowell And Ulf Bandgren Night Visitor Origin Eric Reed A Light In Darkness WJ3 Katharine McPhee I Fall In Love Too Easily BMG Takaaki Otomo New Kid In Town Troy Dr. Lonnie Smith All In My Mind Blue Note Clovis Nicolas Freedom Suite Ensuite Sunnyside Wayne Escoffery Vortex Sunnyside Steve Hobbs Tribute To Bobby Challenge Adam Shulman Full Tilt Cellar Live` Scott Hamilton Live At Pyat Hall Cellar Live Keith O’ Rourke Sketches From The Road Chronograph Jason Marsalis Melody Reimagined Book One Basin Street 1 Ed Love's Highly Recommended New CDs for 2018 Artist Title Label Dan Block Block Party High Michael Waldrop Origin Suite Origin Roberto Margris Live In Miami J Mood Dan Pugach Nonet Plus One Unit UTR Jeff Hamilton Live From San Pedro Capri Phil Stewart Melodious Drum Cellar Live Ben Paterson That Old Feeling Cellar Live Jemal Ramirez African Skies Joyful Beat Michael Dease Reaching Out Positone Ken Fowser Don’t Look Down Positone New Faces Straight Forward Positone Emmet Cohen With Ron Carter Masters Legacy Series Volume Two Cellar Live Bob Washut Journey To Knowhere N/C Mike Jones and Penn Jillette The Show Before The Show Capri 2 Ed Love's Highly Recommended New CDs for 2018 Artist Title Label Dave Tull Texting And Driving Toy Car Corcoran Holt The Mecca Holt House Music Bill Warfield For Lew Planet Arts Wynton Marsalis United We Swing Blue Engine Scott Reeves Without A Trace Origin -

Complexity Through Interaction

Complexity Through Interaction An investigation into the spontaneous development of collective musical ideas from simple thematic materials Nicholas Tasman Haywood M.Music Performance, The University of Melbourne (Victorian College of the Arts) Submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania Hobart (June 2014) ii DECLARATION This exegesis contains the results of research carried out at the University of Tasmania, Conservatorium of Music between 2010 and 2013. It contains no material that, to my knowledge, has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information that is duly acknowledged in the exegesis. I declare that this exegesis is my own work and contains no material previously published or written by another person except where clear acknowledgement or reference has been made in the text. This exegesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Nicholas Tasman Haywood Date ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................. iv List of Figures ............................................................................................................ v Abstract ................................................................................................................... vi Chapter 1 ................................................................................................................. -

Michael Brecker Chronology

Michael Brecker Chronology Compiled by David Demsey • 1949/March 29 - Born, Phladelphia, PA; raised in Cheltenham, PA; brother Randy, sister Emily is pianist. Their father was an attorney who was a pianist and jazz enthusiast/fan • ca. 1958 – started studies on alto saxophone and clarinet • 1963 – switched to tenor saxophone in high school • 1966/Summer – attended Ramblerny Summer Music Camp, recorded Ramblerny 66 [First Recording], member of big band led by Phil Woods; band also contained Richie Cole, Roger Rosenberg, Rick Chamberlain, Holly Near. In a touch football game the day before the final concert, quarterback Phil Woods broke Mike’s finger with the winning touchdown pass; he played the concert with taped-up fingers. • 1966/November 11 – attended John Coltrane concert at Temple University; mentioned in numerous sources as a life-changing experience • 1967/June – graduated from Cheltenham High School • 1967-68 – at Indiana University for three semesters[?] • n.d. – First steady gigs r&b keyboard/organist Edwin Birdsong (no known recordings exist of this period) • 1968/March 8-9 – Indiana University Jazz Septet (aka “Mrs. Seamon’s Sound Band”) performs at Notre Dame Jazz Festival; is favored to win, but is disqualified from the finals for playing rock music. • 1968 – Recorded Score with Randy Brecker [1st commercial recording] • 1969 – age 20, moved to New York City • 1969 – appeared on Randy Brecker album Score, his first commercial release • 1970 – co-founder of jazz-rock band Dreams with Randy, trombonist Barry Rogers, drummer Billy Cobham, bassist Doug Lubahn. Recorded Dreams. Miles Davis attended some gigs prior to recording Jack Johnson. -

Short Takes Jazz News Festival Reviews Jazz Stories Interviews Columns

THE INDEPENDENT JOURNAL OF CREATIVE IMPROVISED MUSIC SHORT TAKES JAZZ NEWS FESTIVAL REVIEWS JAZZAMANCA 2020 JAZZ STORIES PATTY WATERS INTERVIEWS PETER BRÖTZMANN BILL CROW CHAD LEFOWITZ-BROWN COLUMNS NEW ISSUES - REISSUES PAPATAMUS - CD REVIEWS OBITURARIES Volume 46 Number 2 April May June Edition 2020 Ed Schuller (bassist, composer) on GM Recordings My name is Eddy I play the bass A kind of music For the human race And with beauty and grace Let's stay on the case As we look ahead To an uncertain space Peace, Music Love and Life" More info, please visit: www.gmrecordings.com Email: [email protected] GM Recordings, Inc. P.O. Box 894 Wingdale, NY 12594 3 | CADENCE MAGAZINE | APRIL MAY JUNE 2016 L with Wolfgang Köhler In the Land of Irene Kral & Alan Broadbent Live at A-Trane Berlin “The result is so close, so real, so beautiful – we are hooked!” (Barbara) “I came across this unique jazz singer in Berlin. His live record transforms the deeply moving old pieces into the present.” (Album tip in Guido) “As a custodian of tradition, Leuthäuser surprises above all with his flawless intonation – and that even in a live recording!” (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung) “Leuthäuser captivates the audience with his adorable, youthful velvet voice.” (JazzThing) distributed by www.monsrecords.de presents Kądziela/Dąbrowski/Kasper Tom Release date: 20th March 2020 For more information please visit our shop: sklep.audiocave.pl or contact us at [email protected] The latest piano trio jazz from Quadrangle Music Jeff Fuller & Friends Round & Round Jeff Fuller, bass • Darren Litzie, piano • Ben Bilello, drums On their 4th CD since 2014, Jeff Fuller & Friends provide engaging original jazz compositions in an intimate trio setting. -

ON JAZZ Willis "Gatortall" Jackson Begins His First Miller and Dick Cary

x::+}..: A i'_'........:....,:....,..........:.?"`+:..:............ .; ,.,?`e:bº:Ó'ó6.`i;.. ::..:..a ON JAZZ Willis "Gatortall" Jackson begins his first Miller and Dick Cary. TOP 40 L BUMS European tour in his more than thirty-year The First Harlem Jazz Festival will be career next week. Joining Jackson will be held August 17-31. This unique event will longtime associates Carl Wilson, Boogaloo have three different shows each night dur- Joe Jones and Joe Hedrick. The tour will W--- Weeks ing the period. Aiding the ambiance of the On last about three weeks and will include Festival is the fact that the performances 8,5 8/5 Chart stops in Belgium, Holland and France. will be held in clubs for the most part. 1 SOUNDS AND STUFF Jackson's latest album is "Bar Wars" on Small's Paradise, Celebrity Club, ... 21 MY SONG Cotton LIKE THAT! KEITH JARRETT (ECM -1-1115) 27 2 Muse. Club and Vincent's Place will be the main QUINCY JONES (A&M SP 4685) 1 8 The Jazzmobile lineup for this week in- locations. 22 MONTREUX SUMMIT ARTISTS cludes performances by Frank Foster, Bob to 2 FEELS SO GOOD VARIOUS Oregon Electra/Asylum with an album CHUCK MANGIONE (A&M SP 4658) 2 41 (Columbia JG 35090) 23 5 Cunningham, Art Blakey and The Jazz for September release titled, "Out Ot The Messengers, Junior Cook, Bill Hardman Woods." The band thinks it is their best yet. 3 IMAGES 23 PAT METHENY GROUP BA -6030) 4 5 (ECM -1-1114) 28 2 Charles Rouse and Hugh Lawson. Also coming up on E/A will be LPs by CRUSADERS (ABC Jazz A Cordes, a young, swinging band Donald Byrd and Patrice Rushen. -

Reggie Workman Working Man

APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM REGGIE WORKMAN WORKING MAN JIM JONNY RICHARD EDDIE McNEELY KING WYANDS JEFFERSON Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JIM Mcneely 6 by ken dryden [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JONNY KING 7 by donald elfman General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : REGGIE WORKMAN 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : RICHARD WYANDS by marilyn lester Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest WE Forget : EDDIE JEFFERSON 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : MINUS ZERO by george grella US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviews 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne -

Lists of Members 1996

Lists of Members Governing Bodies, Faculties, Boards, Academic and Administrative Staff 1996 Main Committees and Departmental Lists as at 1st February, 1996. Address All general correspondence directed to the University should be addressed to The Registrar, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria. Australia, 3052. Telephone: (03) 9344 4000 Fax: (03) 9344 5104 Contents UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE: SENIOR OFFICE BEARERS COUNCIL 1 *COMMI 11tES 2 4 COUNCILS OF HALLS OF RESIDENCE COMMITthE OF CONVOCATION 8 *ACADEMIC BOARD FACULTIES 10 BOARDS 13 PROFESSORS 21 22 PROFESSORIAL ASSOCIATES WITH 1-11LE OF PROFESSOR 28 READERS 30 PROFESSORS EMERITUS 35 HEADS OF AFFILIATED COLLEGES 40 HEADS OF HALLS OF RESIDENCE 40 TEACHING AND RESEARCH STAFF - Agriculture, Forestry and Horticulture 41 Architecture, Building and Planning 45 Arts 46 Economics and Commerce 53 Education 56 Engineering 60 Law 65 Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences 67 Melbourne Business School 99 Music 100 Science 101 Veterinary Science 107 Victorian College of the Arts 109 LIBRARY 112 FACULTY ADMINISTRATION 115 GRADUATE SCHOOL ADMINISTRATION 119 CENTRAL ADMINISTRATION 120 Office of the Vice-Chancellor and Principal 120 Academic Registrar's Division 122 Academic Services 122 Academic Administration 122 Academic Planning Support Unit 122 External Relations 122 The Graduate Centre 123 International Office 123 Student and Staff Services 123 Human Resources 125 Registrar's Division 126 Executive Services 126 Financial Operations 126 Information -

The Tony Gould Quartet Live in Concert Featuring Graeme Lyall

THE TONY GOULD QUARTET LIVE IN CONCERT FEATURING GRAEME LYALL 1 he main purpose of this recording likes of the Lyall, who has never been even if only for posterity. (The producer is to document the playing of one of remotely interested in promoting his own of this recording, Martin Wright, is one Tthe great jazz saxophonists. extraordinary talent. He reminds one of the few in this country who have a The number of recorded performances of the great Paul Desmond, who might conscience in this regard, and thankfully by Graeme Lyall is shamefully small. It never have been heard had it not been for it extends right across the spectrum of is a classic case of ‘cultural cringe’ in that Brubeck. Desmond, too, by the way, was art music. Some future history of music while this country continues to enjoy visits quiet of nature, which probably accounts in this country will confirm this man’s by outstanding jazz players from overseas, for the sheer beauty of sound both these contribution.) most of whom record prolifically, we tend musicians produce. And so the pieces here were recorded still to ignore some of the marvellous Not many people make a real effort to in two venues, not always under ideal talent ‘on our doorstep’, especially the ensure that we record such musicians, conditions for recording, but given the above, well worth the trouble. These are all well known and much loved pieces. All the performances are spontaneous in every way. Rehearsals consisted of coffee all round, friendly debate about which pieces to play, and what key to play them in, not necessarily the same one each time! The only thing left was to argue about who announces the pieces. -

Downloaded PDF File of the Original First-Edi- Pete Extracted More Music from the Song Form of the Chart That Adds Refreshing Contrast

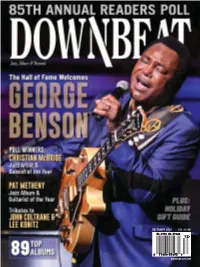

DECEMBER 2016 VOLUME 83 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob; North Carolina: Robin -

International Jazz News Festival Reviews Concert

THE INDEPENDENT JOURNAL OF CREATIVE IMPROVISED MUSIC INTERNATIONAL JAZZ NEWS TOP 10 ALBUMS - CADENCE CRITIC'S PICKS, 2019 TOP 10 CONCERTS - PHILADEPLHIA, 2019 FESTIVAL REVIEWS CONCERT REVIEWS CHARLIE BALLANTINE JAZZ STORIES ED SCHULLER INTERVIEWS FRED FRITH TED VINING PAUL JACKSON COLUMNS BOOK LOOK NEW ISSUES - REISSUES PAPATAMUS - CD Reviews OBITURARIES Volume 46 Number 1 Jan Feb Mar Edition 2020 CADENCE Mainstream Extensions; Music from a Passionate Time; How’s the Horn Treating You?; Untying the Standard. Cadence CD’s are available through Cadence. JOEL PRESS His robust and burnished tone is as warm as the man....simply, one of the meanest tickets in town. “ — Katie Bull, The New York City Jazz Record, December 10, 2013 PREZERVATION Clockwise from left: Live at Small’s; JP Soprano Sax/Michael Kanan Piano; JP Quartet; Return to the Apple; First Set at Small‘s. Prezervation CD’s: Contact [email protected] WWW.JOELPRESS.COM Harbinger Records scores THREE OF THE TEN BEST in the Cadence Top Ten Critics’ Poll Albums of 2019! Let’s Go In Sissle and Blake Sing Shuffl e Along of 1950 to a Picture Show Shuffl e Along “This material that is nearly “A 32-page liner booklet GRAMMY AWARD WINNER 100 years old is excellent. If you with printed lyrics and have any interest in American wonderful photos are included. musical theater, get these discs Wonderfully done.” and settle down for an afternoon —Cadence of good listening and reading.”—Cadence More great jazz and vocal artists on Harbinger Records... Barbara Carroll, Eric Comstock, Spiros Exaras, -

Downbeat.Com December 2020 U.K. £6.99

DECEMBER 2020 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM DECEMBER 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Catalogue.Pdf

MASTER TAPE SOUND LAB sonic upstream www.MasterTapeSoundLab.com For Orders: [email protected] MASTER TAPE CATALOGUE Masterpieces on Master Tape: 64 Master Tapes, about 30 min. each Limited release on 1 generation 2 track 15 ips IEC master tape dubs: Jazz, Classical, Vocals, other. Pricing & formats: www.mastertapesoundlab.com. Samples & recording process: http://www.reel2reel.tv/transformer/recordings_intro.htm All recordings on this catalogue were licensed for limited master tape release by Master Sound Tape Lab and are hereby offered for personal use only. Any reproduction of the tapes offered here is forbidden and subject to copy right law. "I just received the samples this morning. Utterly brilliant. The finest capture of the natural acoustic I have ever heard". - Howard Popeck, SIMPLY STAX, UK "Wonderful recording - you have captured the airy and spacious acoustic perfectly, there is lovely delicacy in the treble and the mids are liquid; in short, very very analogue." - Mike Kontor, designer of NotePerfect Loudspeakers. "I do love Mercury Living Presence recordings and I thought that the sound was impossible to get again, now you did it!" - Vincenzo Fratello, SAP, Nagra Italy. "In essence, it's audio 'vanity publishing': Metaxas has issued a disc of recordings from his own archives. But the results will simply astound you". Ken Kessler, Hi Fi News & Record Review. A. Jazz: 1. Anita Hustas Trio, BMW EDGE, Melbourne 2005 2-3. Andrea Keller - Jazz Ensemble, BMW EDGE, 2005 Tapes 1&2 4-5. Aaron Choulai Trio at BENNETTS LANE, Melbourne 2005, Tapes 1&2 6-7. Aaron Choulai Trio, at BMW EDGE, 2005, Melbourne, Tapes 1&2 8-9.