20061023-Tertrais-Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GOVT-PUNJAB Waitinglist Nphs.Pdf

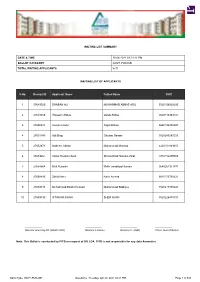

WAITING LIST SUMMARY DATE & TIME 20-04-2021 02:21:11 PM BALLOT CATEGORY GOVT-PUNJAB TOTAL WAITING APPLICANTS 8711 WAITING LIST OF APPLICANTS S No. Receipt ID Applicant Name Father Name CNIC 1 27649520 SHABAN ALI MUHAMMAD ABBAS ADIL 3520106922295 2 27649658 Waseem Abbas Qalab Abbas 3520113383737 3 27650644 Usman Hiader Sajid Abbasi 3650156358657 4 27651140 Adil Baig Ghulam Sarwar 3520240247205 5 27652673 Nadeem Akhtar Muhammad Mumtaz 4220101849351 6 27653461 Imtiaz Hussain Zaidi Shasmshad Hussain Zaidi 3110116479593 7 27654564 Bilal Hussain Malik tasadduq Hussain 3640261377911 8 27658485 Zahid Nazir Nazir Ahmed 3540173750321 9 27659188 Muhammad Bashir Hussain Muhammad Siddique 3520219305241 10 27659190 IFTIKHAR KHAN SHER KHAN 3520226475101 ------------------- ------------------- ------------------- ------------------- Director Housing-XII (LDAC NPA) Director Finance Director IT (I&O) Chief Town Planner Note: This Ballot is conducted by PITB on request of DG LDA. PITB is not responsible for any data Anomalies. Ballot Type: GOVT-PUNJAB Date&time : Tuesday, Apr 20, 2021 02:21 PM Page 1 of 545 WAITING LIST OF APPLICANTS S No. Receipt ID Applicant Name Father Name CNIC 11 27659898 Maqbool Ahmad Muhammad Anar Khan 3440105267405 12 27660478 Imran Yasin Muhammad Yasin 3540219620181 13 27661528 MIAN AZIZ UR REHMAN MUHAMMAD ANWAR 3520225181377 14 27664375 HINA SHAHZAD MUHAMMAD SHAHZAD ARIF 3520240001944 15 27664446 SAIRA JABEEN RAZA ALI 3110205697908 16 27664597 Maded Ali Muhammad Boota 3530223352053 17 27664664 Muhammad Imran MUHAMMAD ANWAR 3520223937489 -

REFORM OR REPRESSION? Post-Coup Abuses in Pakistan

October 2000 Vol. 12, No. 6 (C) REFORM OR REPRESSION? Post-Coup Abuses in Pakistan I. SUMMARY............................................................................................................................................................2 II. RECOMMENDATIONS.......................................................................................................................................3 To the Government of Pakistan..............................................................................................................................3 To the International Community ............................................................................................................................5 III. BACKGROUND..................................................................................................................................................5 Musharraf‘s Stated Objectives ...............................................................................................................................6 IV. CONSOLIDATION OF MILITARY RULE .......................................................................................................8 Curbs on Judicial Independence.............................................................................................................................8 The Army‘s Role in Governance..........................................................................................................................10 Denial of Freedoms of Assembly and Association ..............................................................................................11 -

Copyright © and Moral Rights for This Phd Thesis Are Retained by the Author And/Or Other Copyright Owners

Khan, Adeeba Aziz (2015) Electoral institutions in Bangladesh : a study of conflicts between the formal and the informal. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/id/eprint/23587 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this PhD Thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This PhD Thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this PhD Thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the PhD Thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full PhD Thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD PhD Thesis, pagination. Electoral Institutions in Bangladesh: A Study of Conflicts Between the Formal and the Informal Adeeba Aziz Khan Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in Law 2015 Department of Law SOAS, University of London I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the SOAS, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

Washington's Handprints Found in Pakistan Crisis Management

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 20, Number 29, July 30, 1993 Washington's handprints found in Pakistan crisis management by Susan B. Maitra and Ramtanu Maitra The three-month crisis in Pakistan, which took a full-blown whom are retired Anny men, have also been named. fonn on April 18 with the President dissolving Parliament and sacking the prime minister, has gone into a temporary u.s. meddling lull, with both the President, Ghulam Ishaq Khan, and the Prior to and throughout the crisis, one major player re prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, agreeing to step down. A mained in the shadows, namely Washington. Prime Minister caretaker prime minister and a caretaker President have as Sharif got on the wrong side of Washington when Arab lead sumed control at the center and four provinces of Pakistan, ers, allies of the United States, began complaining early this and preparations for the Oct. 6 national assembly and the year about the training of Muslim guerrillas in Pakistan by Oct. 9 provincial assembly elections have begun. the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence, under the tutelage The crisis had turned into a sordid drama and the country of Javed Nasir, an orthodox Muslim and a close follower of was increasingly ungovernable.During this period, the duly the prime minister. elected Nawaz Sharif governmentand the National Assembly Although Nawaz Sharif had supported the U.S. role in were dissolved by the President, who was already engaged the Gulf war and bent over backwards to accommodate the in a bitter feud with the prime minister. -

4.8B Private Sector Universities/Degree Awarding Institutions Federal 1

4.8b Private Sector Universities/Degree Awarding Institutions Federal 1. Foundation University, Islamabad 2. National University of Computer and Emerging Sciences, Islamabad 3. Riphah International University, Islamabad Punjab 1. Hajvery University, Lahore 2. Imperial College of Business Studies, Lahore 3. Institute of Management & Technology, Lahore 4. Institute of Management Sciences, Lahore 5. Lahore School of Economics, Lahore 6. Lahore University of Management Sciences, Lahore 7. National College of Business Administration & Economics, Lahore 8. University of Central Punjab, Lahore 9. University of Faisalabad, Faisalabad 10. University of Lahore, Lahore 11. Institute of South Asia, Lahore Sindh 1. Aga Khan University, Karachi 2. Baqai Medical University, Karachi 3. DHA Suffa University, Karachi 4. Greenwich University, Karachi 5. Hamdard University, Karachi 6. Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, Karachi 7. Institute of Business Management, Karachi 8. Iqra University, Karachi 9. Isra University, Hyderabad 10. Jinnah University for Women, Karachi 11. Karachi Institute of Economics & Technology, Karachi 12. KASB Institute of Technology, Karachi 13. Muhammad Ali Jinnah University, Karachi 56 14. Newport Institute of Communications & Economics, Karachi 15. Preston Institute of Management, Science and Technology, Karachi 16. Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto Institute of Science and Technology (SZABIST), Karachi 17. Sir Syed University of Engineering and Technology, Karachi 18. Textile Institute of Pakistan, Karachi 19. Zia-ud-Din Medical University, Karachi 20. Biztek Institute of Business Technology, Karachi 21. Dada Bhoy Institute of Higher Education, Karachi NWFP 1. CECOS University of Information Technology & Emerging Sciences, Peshawar 2. City University of Science and Information Technology, Peshawar 3. Gandhara University, Peshawar 4. Ghulam Ishaq Khan Institute of Engineering Sciences & Technology, Topi 5. -

Imports-Exports Enterprise’: Understanding the Nature of the A.Q

Not a ‘Wal-Mart’, but an ‘Imports-Exports Enterprise’: Understanding the Nature of the A.Q. Khan Network Strategic Insights , Volume VI, Issue 5 (August 2007) by Bruno Tertrais Strategic Insights is a bi-monthly electronic journal produced by the Center for Contemporary Conflict at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California. The views expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of NPS, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. Introduction Much has been written about the A.Q. Khan network since the Libyan “coming out” of December 2003. However, most analysts have focused on the exports made by Pakistan without attempting to relate them to Pakistani imports. To understand the very nature of the network, it is necessary to go back to its “roots,” that is, the beginnings of the Pakistani nuclear program in the early 1970s, and then to the transformation of the network during the early 1980s. Only then does it appear clearly that the comparison to a “Wal-Mart” (the famous expression used by IAEA Director General Mohammed El-Baradei) is not an appropriate description. The Khan network was in fact a privatized subsidiary of a larger, State-based network originally dedicated to the Pakistani nuclear program. It would be much better characterized as an “imports-exports enterprise.” I. Creating the Network: Pakistani Nuclear Imports Pakistan originally developed its nuclear complex out in the open, through major State-approved contracts. Reprocessing technology was sought even before the launching of the military program: in 1971, an experimental facility was sold by British Nuclear Fuels Ltd (BNFL) in 1971. -

QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD 18 RESULT GAZETTE of B.A/B.Sc./B.Com SUPPL

18 QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD RESULT GAZETTE OF B.A/B.Sc./B.Com SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2015 (Part-II) Reg. No. Roll No. Name Father Name Status Marks Remarks (002) 110021310011 3000002 Syed Afaq Hussain Syed Amin Hussain COMPT. ENG:II 110021310001 3000003 Syed Atif Hussain Syed Sajid Hussain Shah PASS 430 110021310004 3000004 Mahr Ahmad Kamal Mahr Shabbir Hussain COMPT. ENG:II 110021310006 3000005 Shahzad Ahmed Ashiq Hussain COMPT. ENG:II 110021310007 3000006 Wali Khan Khowazik PASS 441 110021310013 3000007 Muhammad Ehsan Juma Khan PASS 437 110021310014 3000008 Mujahid Din Roz Din COMPT. ENG:II ENG-LIT:II 110021310015 3000009 Mehtab arshad Arshad Mehmood COMPT. ENG:II 110021310018 3000010 Mahr Muhammad Ijlal Mahr Shabbir Hussain COMPT. ECO:I ECO:II 110021310021 3000011 Sammar Abbas Muhammad Ismail PASS 436 110021310022 3000012 Muhammad Riaz Muhammad Hussain COMPT. ENG:II 110021310026 3000013 Anas Ayaz Ayaz Ahmad COMPT. ECO:I 110021310027 3000014 Muhammad Shahzad Muhammad khursheed COMPT. ENG:II APP-PSY:II 110021310029 3000015 Shahab U Din Ch Zaheer Ud Din Ahmed PASS 384 110021310031 3000016 Muzaffar Sultan Muhammad Sultan Khan PASS 453 110021310033 3000017 Sohail Iqbal Muhammad Iqbal COMPT. ENG:II 110021310034 3000018 Malik Waqar Ahmed Malik Iftikhar Ahmad COMPT. ENG:I 110021310035 3000019 Waqar Haider Ghulam Haider COMPT. ENG:I ENG:II 110021310036 3000020 Arif Zaman Mehran Khan PASS 434 110021310038 3000021 Fahad Raza Muhammad Muslimeen COMPT. ENG:I ENG-LIT:II 110021310039 3000022 Mubasher Nawaz Muhammad Nawaz PASS 423 19 QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD RESULT GAZETTE OF B.A/B.Sc./B.Com SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2015 (Part-II) Reg. -

Pakistan's Nuclear Future

CHAPTER 1 PAKISTAN’S NUCLEAR WOES Henry D. Sokolski Raise the issue of Pakistan’s nuclear program before almost any group of Western security analysts, and they are likely to throw up their hands. What might happen if the current Pakistani government is taken over by radicalized political forces sympathetic to the Taliban? Such a government, they fear, might share Pakistan’s nuclear weapons materials and know-how with others, including terrorist organizations. Then there is the possibility that a more radical government might pick a war again with India. Could Pakistan prevail against India’s superior conventional forces without threatening to resort to nuclear arms? If not, what, if anything, might persuade Pakistan to stand its nuclear forces down? There are no good answers to these questions and even fewer near or mid-term fixes against such contingencies. This, in turn, encourages a kind of policy fatalism with regard to Pakistan. This book, which reflects research that the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center commis- sioned over the last 2 years, takes a different tack. Instead of asking questions that have few or no good answers, this volume tries to characterize specific nuclear problems that the ruling Pakistani government faces with the aim of establishing a base line set of challenges for remedial action. Its point of departure is to consider what nuclear challenges Pakistan will face if moderate forces remain in control of the government and no hot war breaks out against India. A second volume of commissioned research planned for 1 publication in 2008 will consider how best to address these challenges. -

C05516700.Pdf

'C00175067 Page: 116 of 170 UNCLASSIFIED Document 61 CLAS UNCLASSIFIED CLAS UNCLASSIFIED APSN TB1506101591C PROM PaIS LONDON UK SUBJ TAKEALL-- Comllst: Moscow Consolidated 14 Jun 91 Full Text Super zone of Message 1 GLOBAL 2 1 "intl situation: questions and answers": viktor levin on nato's future as discussed in recent bessmertnykh-genscher talks (4 min, sent); in reply to two letters which regret loss of eastern europe to socialism and note onset of anarchy and famine there, gubernatorov talks to k. pat syuk , who does not believe that all the sacrificies made by soviet ppl to secure victory in VVII were made only to split germany and its ppl for an indefinite period and to try to implant soviet ways in europe (5 min); civil engineer from krasnodar kray asks why usa is so stubbornly seeking to retain their military bases in philippines? gubernatorov quotes armitage as saying that u.s. future is linked with asia, further quotes from intl herald tribune and u.s. marine general grey (4 min); letter from ventspils raises question of use of force abroad by usa on pretext of defending its interests, gubernator quotes from nixon's book "real war," published in 1980 in which he exhorts his successors on need to learn to make effective use of force for defending u.s. interests, casey quoted on range of these interests, quotes from white house document for u.s. ambassadors and cia issued 10 yeara ago as guide for action, from shultz stmt in '83 on usa having sent armed forces to developing countries VVII (5 min); gubernatorov chats to sergey pravdin in reply to kiev teacher's question about circumstances in which u.s. -

Senate Foreign Relations Committee

SENATE OF PAKISTAN PAKISTAN WORLDVIEW Report - 21 SENATE FOREIGN RELATIONS COMMITTEE Visit to Azerbaijan December, 2008 http://www.foreignaffairscommittee.org List of Contents 1. From the Chairman’s Desk 5 2. Executive Summary 9-14 3. Members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee Delegation to Azerbaijan 17 4. Verbatim record of the meetings held in Azerbaijan: Meeting with Pakistan-Azerbaijan Friendship Group 21-24 Meeting with Permanent Commission of the Milli Mejlis for International and Inter-Parliamentary Relations 25-26 Meeting with Permanent Commission of the Milli Mejlis for Social Affairs 27 Meeting with Permanent Commission of the Milli Mejlis for Security and Defence 28-29 Meeting with Chairman of the Milli Mejlis (National Assembly) 30-34 Meeting with Vice Chairman of New Azerbaijan Party 35-37 Meeting with Minister for Industry and Energy 38-40 Meeting with President of the Republic of Azerbaijan 41-44 Meeting with the Foreign Minister 45-47 Meeting with the Prime Minister of Azerbaijan 48-50 5. Appendix: Pakistan - Azerbaijan Relations 53-61 Photo Gallery of the Senate Foreing Relations Committee Visit to Azerbaijan 65-66 6. Profiles: Profiles of the Chairman and Members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee 69-76 Profiles of the Committee Officials 79-80 03 Visit to Azerbaijan From the Chairman’s Desk The Report on Senate Foreign Relations Committee visit to Azerbaijan is of special significance. Azerbaijan emerged as an independent country in 1991 with the breakup of Soviet Union, along with five other Central Asian states. Pakistan recognized it shortly after its independence and opened diplomatic relations with resident ambassadors in the two capitals. -

Analysis of Growth Rates in Different Regimes of Pakistan: Distribution and Forecasting Anwar Hussain ∗ & Naila Nazir ∗∗

Analysis of Growth Rates in Different Regimes of Pakistan: Distribution and Forecasting Anwar Hussain ∗ & Naila Nazir ∗∗ Abstract The present study aims to analyze the growth rate distribution pattern in different regimes of Pakistan and also forecasts the growth rates of agricultural, industrial, services and GDP growth rates in Pakistan. The study uses secondary data ranging from 1956 to 2011. The data from 1956 to 2000 has been obtained from State Bank of Pakistan and from 2001 to 2011 from Economic Survey of Pakistan. For the analysis of the regime-wise distribution of growth rates, the Gini-coefficient and Lorenz curve are used. While for forecasting the growth rates, moving average forecast and exponential smoothing method have been used. The findings revealed that the Gini-coefficients for agriculture, industrial, services and GDP growth rates were 0.161453, 0.214199, 0.147940 and 0.112955. The Lorenz curve also suggests equality between selected growth rates regime-wise. The moving average forecasts for agriculture, industrial, services sector and GDP growth rates in the year 2012 is 1.7%, 2.7%, 2.9% and 3.1% respectively for the year 2012. According to the exponential smoothing method these growth rates in the year 2012 are projected to be 1.9%, 3.1%, 3.8% and 3.3% respectively. Looking over the growth distribution pattern, there is a need to take revolutionary steps and big push to boost the macroeconomic variables performance in Pakistan. Based on the forecasting results, the services sector may decline in next year, which needs to be focused on. Key words : Growth Rates, Distribution, Lorenz Curve, Gini-coefficient, Forecasting, Moving Average, Exponential Smoothing. -

3 Who Is Who and What Is What

3 e who is who and what is what Ever Success - General Knowledge 4 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Ever Success Revised and Updated GENERAL KNOWLEDGE Who is who? What is what? CSS, PCS, PMS, FPSC, ISSB Police, Banks, Wapda, Entry Tests and for all Competitive Exames and Interviews World Pakistan Science English Computer Geography Islamic Studies Subjectives + Objectives etc. Abbreviations Current Affair Sports + Games Ever Success - General Knowledge 5 Saad Book Bank, Lahore © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this book may be reproduced In any form, by photostate, electronic or mechanical, or any other means without the written permission of author and publisher. Composed By Muhammad Tahsin Ever Success - General Knowledge 6 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Dedicated To ME Ever Success - General Knowledge 7 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Ever Success - General Knowledge 8 Saad Book Bank, Lahore P R E F A C E I offer my services for designing this strategy of success. The material is evidence of my claim, which I had collected from various resources. I have written this book with an aim in my mind. I am sure this book will prove to be an invaluable asset for learners. I have tried my best to include all those topics which are important for all competitive exams and interviews. No book can be claimed as prefect except Holy Quran. So if you found any shortcoming or mistake, you should inform me, according to your suggestions, improvements will be made in next edition. The author would like to thank all readers and who gave me their valuable suggestions for the completion of this book.