A Note on the Black Honeyeater by C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Breeding Record of the Black Honeyeater at Port Neill, Eyre Peninsula

76 SOUTH AUSTRALIAN ORNITHOLOGIST, 30 BREEDING RECORD OF THE BLACK HONEYEATER AT PORT NEILL, EYRE PENINSULA TREVOR COX Eckert et al. (1985) pointed out that the Black indicated by dead branches protruding slightly Honeyeater Certhionyx niger has been reported above the vegetation. The male would perch on from Eyre Peninsula but that its occurrence there each branch in turn for approximately one minute requires substantiation. In this note, I report the and repeatedly give a single note call. Display occurrence and breeding ofBlack Honeyeaters on flights at this time attained a height of 1O-12m and the Peninsula. the female was only heard occasionally, uttering a On 5 October 1985, I saw, six to ten Black soft, single note call from the nest area. The male Honeyeaters in a small patch of scrub on a rise defended the territory against other Black adjacent to the southern edge of the township of Honeyeaters, a Singing Honeyeater Port Neill on Eyre Peninsula. The scrub consisted Lichenostomus virescens and a Tawny-crowned of stunted maIlee, Broomebush Melaleuca Honeyeater Gliciphila melanops. It chased the uncinata, Porcupine Grass Triodia irritans and latter 50m on one occasion. shrubs. The only eucalypt flowering at the time The nest wasin a stunted mallee at 0.35m height. was Red Mallee Eucalyptus socialis. It was a small cup 55mm in diameter and 40mm A description taken from my field notes of the deep, made of fine sticks bound with spider web, birds seen at Port Neill is as follows: lined with hair roots and adorned with pieces of A small honeyeater of similar size to silvereye [Zosterops], barkhanging from it. -

Bird Guide for the Great Western Woodlands Male Gilbert’S Whistler: Chris Tzaros Whistler: Male Gilbert’S

Bird Guide for the Great Western Woodlands Male Gilbert’s Whistler: Chris Tzaros Whistler: Male Gilbert’s Western Australia PART 1. GWW NORTHERN Southern Cross Kalgoorlie Widgiemooltha birds are in our nature ® Australia AUSTRALIA Introduction The birds and places of the north-west region of the Great Western Woodlands are presented in this booklet. This area includes tall woodlands on red soils, shrublands on yellow sand plains and mallee on sand and loam soils. Landforms include large granite outcrops, Banded Ironstone Formation (BIF) Ranges, extensive natural salt lakes and a few freshwater lakes. The Great Western Woodlands At 16 million hectares, the Great Western Woodlands (GWW) is close to three quarters the size of Victoria and is the largest remaining intact area of temperate woodland in the world. It is located between the Western Australian Wheatbelt and the Nullarbor Plain. BirdLife Australia and The Nature Conservancy joined forces in 2012 to establish a long-term project to study the birds of this unique region and to determine how we can best conserve the woodland birds that occur here. Kalgoorlie 1 Groups of volunteers carry out bird surveys each year in spring and autumn to find out the species present, their abundance and to observe their behaviour. If you would like to know more visit http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/great-western-woodlands If you would like to participate as a volunteer contact [email protected]. All levels of experience are welcome. The following six pages present 48 bird species that typically occur in four different habitats of the north-west region of the GWW, although they are not restricted to these. -

Understanding Variation in Migratory Movements: a Mechanistic Approach ⇑ Heather E

General and Comparative Endocrinology 256 (2018) 112–122 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect General and Comparative Endocrinology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ygcen Review Understanding variation in migratory movements: A mechanistic approach ⇑ Heather E. Watts a,b, , Jamie M. Cornelius c, Adam M. Fudickar d, Jonathan Pérez e, Marilyn Ramenofsky e a Department of Biology, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, CA 90045, USA b School of Biological Sciences, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164, USA c Biology Department, Eastern Michigan University, MI 48197, USA d Environmental Resilience Institute, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405, USA e Department of Neurobiology, Physiology & Behavior, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA article info abstract Article history: Spatial and temporal fluctuations in resource availability have led to the evolution of varied migration Received 1 May 2017 patterns. In order to appropriately time movements in relation to resources, environmental cues are used Revised 20 July 2017 to provide proximate information for timing and the endocrine system serves to integrate these external Accepted 25 July 2017 cues and behavioral and physiological responses. Yet, the regulatory mechanisms underlying migratory Available online 26 July 2017 timing have rarely been compared across a broad range of migratory patterns. First, we offer an updated nomenclature of migration using a mechanistic perspective to clarify terminology describing migratory Keywords: types in relation to ecology, behavior and endocrinology. We divide migratory patterns into three types: Facultative migration obligate, nomadic, and fugitive. Obligate migration is characterized by regular and directed annual move- Partial migration Fugitive ments between locations, most commonly for breeding and overwintering, where resources are pre- Nomadic dictable and sufficient. -

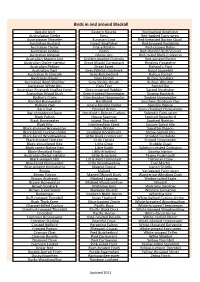

Birds in and Around Blackall

Birds in and around Blackall Apostle bird Eastern Rosella Red backed Kingfisher Australasian Grebe Emu Red-backed Fairy-wren Australasian Shoveler Eurasian Coot Red-breasted Button Quail Australian Bustard Forest Kingfisher Red-browed Pardalote Australian Darter Friary Martin Red-capped Robin Australian Hobby Galah Red-chested Buttonquail Australian Magpie Glossy Ibis Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo Australian Magpie-lark Golden-headed Cisticola Red-winged Parrot Australian Owlet-nightjar Great (Black) Cormorant Restless Flycatcher Australian Pelican Great Egret Richard’s Pipit Australian Pipit Grey (White) Goshawk Royal Spoonbill Australian Pratincole Grey Butcherbird Rufous Fantail Australian Raven Grey Fantail Rufous Songlark Australian Reed Warbler Grey Shrike-thrush Rufous Whistler Australian White Ibis Grey Teal Sacred Ibis Australian Ringneck (mallee form) Grey-crowned Babbler Sacred Kingfisher Australian Wood Duck Grey-fronted Honeyeater Singing Bushlark Baillon’s Crake Grey-headed Honeyeater Singing Honeyeater Banded Honeyeater Hardhead Southern Boobook Owl Barking Owl Hoary-headed Grebe Spinifex Pigeon Barn Owl Hooded Robin Spiny-cheeked Honeyeater Bar-shouldered Dove Horsfield's Bronze-Cuckoo Splendid Fairy-wren Black Falcon House Sparrow Spotted Bowerbird Black Honeyeater Inland Thornbill Spotted Nightjar Black Kite Intermediate Egret Square-tailed kite Black-chinned Honeyeater Jacky Winter Squatter Pigeon Black-faced Cuckoo-shrike Laughing Kookaburra Straw-necked Ibis Black-faced Woodswallow Little Black Cormorant Striated Pardalote -

Threatened and Declining Birds in the New South Wales Sheep-Wheat Belt: Ii

THREATENED AND DECLINING BIRDS IN THE NEW SOUTH WALES SHEEP-WHEAT BELT: II. LANDSCAPE RELATIONSHIPS – MODELLING BIRD ATLAS DATA AGAINST VEGETATION COVER Patchy but non-random distribution of remnant vegetation in the South West Slopes, NSW JULIAN R.W. REID CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, GPO Box 284, Canberra 2601; [email protected] NOVEMBER 2000 Declining Birds in the NSW Sheep-Wheat Belt: II. Landscape Relationships A consultancy report prepared for the New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service with Threatened Species Unit (now Biodiversity Management Unit) funding. ii THREATENED AND DECLINING BIRDS IN THE NEW SOUTH WALES SHEEP-WHEAT BELT: II. LANDSCAPE RELATIONSHIPS – MODELLING BIRD ATLAS DATA AGAINST VEGETATION COVER Julian R.W. Reid November 2000 CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems GPO Box 284, Canberra 2601; [email protected] Project Manager: Sue V. Briggs, NSW NPWS Address: C/- CSIRO, GPO Box 284, Canberra 2601; [email protected] Disclaimer: The contents of this report do not necessarily represent the official views or policy of the NSW Government, the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, or any other agency or organisation. Citation: Reid, J.R.W. 2000. Threatened and declining birds in the New South Wales Sheep-Wheat Belt: II. Landscape relationships – modelling bird atlas data against vegetation cover. Declining Birds in the NSW Sheep-Wheat Belt: II. Landscape Relationships Consultancy report to NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, Canberra. ii Declining Birds in the NSW Sheep-Wheat Belt: II. Landscape Relationships Threatened and declining birds in the New South Wales Sheep-Wheat Belt: II. -

Recent Literature

Vol.lo4•XII RecentLiterature [177 RECENT LITERATURE Reviews by Margaret M. Nice BANDING 1. Report of the Bird-Ringing Committee: Progress for 1940. A.L. Thomson. 1941. Brit. Birds, 35:9-14. The Fourth Annual Report of the Bird-Ringing Committee of the British Trust for Ornithology showsa total of 21,182 birds ringed in 1940, nearly 15,000 beingtrapped birds and 6,000 nestlings. Economy.has to be observedin the use of rings. "Further suppliesof aluminum cannot be expectedduring the war." "Valuable help in reporting recoverieshas beengiven by localpolice, as a resultof an officialcircular to Chief Constables." Birds with foreign rings "have been the subject of somesuspicion." 2. Results of Ringing Duck. General Survey of Data from all Sources. A. L. Thomson. 1941. International Wildfowl Iwuiry, 1: 84-105. Univ. Press, Cambridge, Eng. A very interestingsummary of Old World data with seven maps,a discussionof resultsof ringingin the breedingquarters, wintering quarters, and on migration, wi•h notes on anomalousbehavior of individuals, as when a Mallard raised in England breedsin Sweden,etc. Although duck populationsin Great Britain are mainly stationary, on the whole most of the ducksseem highly migratory,while many of themexhibit a widevariety in routes. No. 16 is basedon the technique of color banding. MIGRATION 3. Homing and Earth Magnetism.--(Heimfindeversuche und Erdmag- netismus.) A. Daanje. 1941. Vogelzug,12:15-17. A discussionof Strese- mann's theory which is basedon that of Viguier, and of experimentsin this field. Casamajorand Wodzicki placed magnetson birds' headswith negative results; such contrivances are very unpleasant to birds and disturb their behavior. Schein'sstarlings raised in captivity failed to return when releasedat a distance; Daanje believesthis due to the wire cagein whichthey were kept, for this would confusethe magnetic field. -

SBOC Full Bird List

Box 1722 Mildura Vic 3502 BirdLife Mildura - Full Bird List Please advise if you see birds not on this list Date Notes Locality March 2012 Observers # Denotes Rarer Species Emu Grey Falcon # Malleefowl Black Falcon Stubble Quail Peregrine Falcon Brown Quail Brolga Plumed Whistling-Duck Purple Swamphen Musk Duck Buff-banded Rail Freckled Duck Baillon's Crake Black Swan Australian Spotted Crake Australian Shelduck Spotless Crake Australian Wood Duck Black-tailed Native-hen Pink-eared Duck Dusky Moorhen Australasian Shoveler Eurasian Coot Grey Teal Australian Bustard # Chestnut Teal Bush Stone-curlew Pacific Black Duck Black-winged Stilt Hardhead Red-necked Avocet Blue-billed Duck Banded Stilt Australasian Grebe Red-capped Plover Hoary-headed Grebe Double-banded Plover Great Crested Grebe Inland Dotterel Rock Dove Black-fronted Dotterel Common Bronzewing Red-kneed Dotterel Crested Pigeon Banded Lapwing Diamond Dove Masked Lapwing Peaceful Dove Australian Painted Snipe # Tawny Frogmouth Latham's Snipe # Spotted Nightjar Black-tailed Godwit Australian Owlet-nightjar Bar-tailed Godwit White-throated Needletail Common Sandpiper # Fork-tailed Swift Common Greenshank Australasian Darter Marsh Sandpiper Little Pied Cormorant Wood Sandpiper # Great Cormorant Ruddy Turnstone Little Black Cormorant Red-necked Stint Pied Cormorant Sharp-tailed Sandpiper Australian Pelican Curlew Sandpiper Australasian Bittern Painted Button-quail # Australian Little Bittern Red-chested Button-quail White-necked Heron Little Button-quail Eastern Great Egret Australian -

08B Murchison.Cdr

RATITE COCKATOO, PARROT HONEYEATER, CHAT BUTCHERBIRD, Emu Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo Pied Honeyeater CURRAWONG Major Mitchell's Cockatoo Singing Honeyeater Pied Butcherbird QUAIL Galah Grey-fronted Honeyeater Australian Magpie Stubble Quail Little Corella White-plumed Honeyeater Cockatiel White-fronted Honeyeater FANTAIL PIGEON, DOVE Australian Ringneck Yellow-throated Miner Grey Fantail Common Bronzewing Mulga Parrot Spiny-cheeked Honeyeater Willie Wagtail Crested Pigeon Budgerigar Crimson Chat Diamond Dove Bourke's Parrot White-fronted Chat RAVEN, CROW Black Honeyeater Little Crow FROGMOUTH CUCKOO Brown Honeyeater Torresian Crow Tawny Frogmouth Horsfield's Bronze-Cuckoo Black-eared Cuckoo BABBLER FLYCATCHER, MONARCH NIGHTJAR Pallid Cuckoo Grey-crowned Babbler Magpie-lark Spotted Nighjar White-browed Babbler Australian Owlet-nightjar OWL ROBIN, SCRUB-ROBIN Southern Boobook QUAIL-THRUSH, ALLIES Hooded Robin RAPTOR Varied Sittella Black-shouldered Kite KINGFISHER, ALLIES OLD WORLD WARBLER Black-breasted Buzzard Red-backed Kingfisher CUCKOO-SHRIKE, TRILLER Rufous Songlark Whistling Kite Sacred Kingfisher Ground Cuckoo-shrike Brown Songlark Brown Goshawk Black-faced Cuckoo-shrike Collared Sparrowhawk FAIRY-WREN, GRASSWREN White-winged Triller SWALLOW, MARTIN Spotted Harrier Splendid Fairy-wren White-backed Swallow Little Eagle White-winged Fairy-wren WHISTLER, SHRIKE- Welcome Swallow Nankeen Kestrel THRUSH Tree Martin Brown Falcon SCRUBWREN, ALLIES Rufous Whistler Redthroat Grey Shrike-thrush FINCH SHOREBIRD Western Gerygone Crested Bellbird Zebra Finch Banded Lapwing Yellow-rumped Thornbill Chestnut-rumped Thornbill WOODSWALLOW PIPIT BUTTON-QUAIL Southern Whiteface Black-faced Woodswallow Australasian Pipit Little Button-quail PARDALOTE Striated Pardalote This is a record of bird sightings within a kilometre walk of the Prepared by Birds Australia Murchison Settlement. Western Australia Please report any unlisted sightings to the Murchison Museum or to the office of Birds Australia Western Australia. -

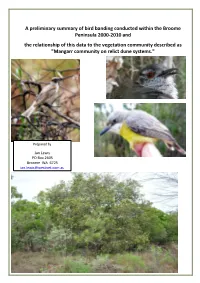

A Preliminary Summary of Bird Banding Conducted Within The

A preliminary summary of bird banding conducted within the Broome Peninsula 2000-2010 and the relationship of this data to the vegetation community described as "Mangarr community on relict dune systems." Prepared by Jan Lewis PO Box 2605 Broome WA 6725 [email protected] INTRODUCTION Jan Lewis has been involved in voluntary bird research since 1998 and has assisted in bird surveys conducted by Broome Bird Observatory, the Australasian Wader Study Group, Mornington Wildlife Sanctuary, DEC and Save the Gouldian Fund. Jan became a licensed bird bander in 2000 and currently operates two research projects: o In Broome: Avian dynamics in the coastal habitat of Broome Peninsula o In Wyndham: Comparative ecology of some little known East Kimberley passerines. Jan has published several articles detailing the findings of her research, including articles in Amytornis, the Western Australian Journal of Ornithology: “Ageing and sexing Red-headed Honeyeaters ( Myzomela erythrocephala ), with notes on aspects of the breeding biology” Amytornis 2 (2010). p 15-24. “Timing of breeding and wing moult in the Yellow White-eye ( Zosterops luteus ) near Broome, Western Australia”. Amytornis 3 , (2011). pp13-18. “Synchronous breeding by the Star Finch ( Neochmia ruficauda) in the east Kimberley, WA”. Amytornis 2 (2010), p 25-28. “Post juvenile moult and associated changes in bare parts in Star Finches ( Neochmia ruficauda ) in the Wyndham region of WA”. Accepted for publication in Amytornis volume 4. BACKGROUND Bird research has been conducted in Minyirr Park between the Broome Port and Barred Creek since late 2000 under license from Environment Australia and with the permission of the former Coastal Landcare Management Committee, the Port of Broome and the Yawuru/Goolarabaloo Traditional Owners. -

June 2010 Vol

Castlemaine Naturalist June 2010 Vol. 35.5 #377 Monthly newsletter of the Cortinarius archeri at Sailors Falls Castlemaine Field Naturalists Club Inc. photo - Denis Hurley Terrick Terrick Chris Morris Terrick Terrick , locally known as “The Forest” is 200kms north of Castlemaine and never disappointing but well worth a visit even in dry times. Its an easy drive across the northern plains skirting Bendigo to the park entrance at Mitiamo, another semi- deserted township of inland Victoria. A closed Hotel tells it all. The same at Mologa on the edge of the forest and long since abandoned leaving the remnants of three schools and cottage foundations The isolated granite outcrops and the forest of White Cypress Pines gives it character and marks it out from the surrounding countryside of cleared farmland. The history of the landscape goes back thousands of years judging by the dating of Aboriginal remains and tree scars crafted for canoes which suggests a wetter riverine type of country in earlier times. Lignum Swamps together with Black Box front the dry creeks and provide good nesting hollows. Major Mitchell came through in 1836 and wrote of the fertility of the land as viewed from Pyramid Hill This encouraged the squatters in his wake to take up the land except the small segment of bush which became the forest. There are no other parks close too, just a vast expanse of paddocks – cleared of natural vegetation. Old-timers tell of seemingly thousands of Budgerigars wheeling as one in a flash of color, gold and green. These have gone. As have the Ducks with young in large numbers now that their water is no longer available in dams, swamps and creeks. -

Birds Ofnarran Lake Nature Reserve, New South Wales

38 AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2003, 20, 38-54 Birds ofNarran Lake Nature Reserve, New South Wales ANDREW J. LEY 19 Lynches Road, Armidale, N.S.W 2350 (Email: [email protected]) Summary The 181 species of birds recorded from the Narran Lake Nature Reserve are listed. A further 19 species are on a supplementary list of doubtful records from the Nature Reserve and of potential additions to the full list. Occurrence and breeding activity of waterbirds in the Nature Reserve in 1998-2001 inclusive are documented. The Nature Reserve experienced high floods in October 1998 and April 1999; a large breeding event took place on the first of these but little breeding occurred on the second. Introduction Narran Lake Nature Reserve is in the Western Division of New South Wales between Walgett and Brewarrina. Its location and layout have been mapped previously (Ley 1998a). This bird list has been compiled from observations made during numerous visits to the area since 1985 and is the first complete list published for the Nature Reserve. Public access into Narran Lake Nature Reserve is restricted, and permission to enter should be sought from the National Parks and Wildlife Servic.e (NPWS) office in Narrabri. Special-interest groups may seek permission to enter but general public access for recreation purposes is not permitted. Natural Heritage of Narran Lake Nature Reserve The following description is paraphrased from Hunter (1999) and NPWS (2000). Climate The climate is semi-arid; the average annual rainfall for the ten years· 1990- 99 was 495 mm. There is a long hot summer and a short cold winter with average maximum and minimum temperatures of 36°C and 21 ac, and 18oC and 6°C respectively. -

Australia Queensland Outback 21St July to 4Th August 2020 (15 Days) Cape York Peninsula Extension 3Rd to 12Th August 2020 (10 Days)

Australia Queensland Outback 21st July to 4th August 2020 (15 days) Cape York Peninsula Extension 3rd to 12th August 2020 (10 days) Spinifex Pigeon by Jonathan Rossouw Our Queensland Outback birding adventure explores the remote and scenic corners of Western Queensland and the Gulf Country where many of Australia’s most desirable and seldom-seen endemics await us. RBL Australia – Queensland Outback & Cape York Ext Itinerary 2 This comprehensive tour targets all the region’s specialties in the unique and fascinating spinifex- dominated, stunted-Eucalyptus woodland, arid plains and savannah that covers much of this part of the continent. The birding is truly fantastic and we’ll be searching for a number of rare and little- known gems like Carpentarian and Kalkadoon Grasswrens, Masked, Long-tailed, Painted, Gouldian and Star Finches, Spinifex Pigeon, Spinifexbird, Grey and Black Falcons, Black-chested Buzzard, Red-backed Kingfisher, Ground Cuckooshrike, Purple-crowned Fairywren, Pictorella Mannikin, Rufous-crowned Emu-wren, Hall’s Babbler and Chestnut-breasted Quail-thrush to mention just a few of the possible highlights we hope to encounter on this specialist Australian birding tour. THE TOUR AT A GLANCE… THE QUEENSLAND OUTBACK ITINERARY Day 1 Arrival in Cairns Day 2 Cairns to Georgetown Day 3 Georgetown to Karumba Day 4 Karumba area Day 5 Karumba to Burketown Day 6 Burketown to Boodjamulla National Park Day 7 Boodjamulla National Park Day 8 Boodjamulla National Park to Mount Isa Days 9 & 10 Mount Isa area Day 11 Mount Isa to Winton Day