Noise and Texture, Towards an Asian Influenced Composition Approach to the Concert Flute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4. Non-Heptatonic Modes

Tagg: Everyday Tonality II — 4. Non‐heptatonic modes 151 4. Non‐heptatonic modes If modes containing seven different scale degrees are heptatonic, eight‐note modes are octatonic, six‐note modes hexatonic, those with five pentatonic, while four‐ and three‐note modes are tetratonic and tritonic. Now, even though the most popular pentatonic modes are sometimes called ‘gapped’ because they contain two scale steps larger than those of the ‘church’ modes of Chapter 3 —doh ré mi sol la and la doh ré mi sol, for example— they are no more incomplete FFBk04Modes2.fm. 2014-09-14,13:57 or empty than the octatonic start to example 70 can be considered cluttered or crowded.1 Ex. 70. Vigneault/Rochon (1973): Je chante pour (octatonic opening phrase) The point is that the most widespread convention for numbering scale degrees (in Europe, the Arab world, India, Java, China, etc.) is, as we’ve seen, heptatonic. So, when expressions like ‘thirdless hexatonic’ occur in this chapter it does not imply that the mode is in any sense deficient: it’s just a matter of using a quasi‐global con‐ vention to designate a particular trait of the mode. Tritonic and tetratonic Tritonic and tetratonic tunes are common in many parts of the world, not least in traditional music from Micronesia and Poly‐ nesia, as well as among the Māori, the Inuit, the Saami and Native Americans of the great plains.2 Tetratonic modes are also found in Christian psalm and response chanting (ex. 71), while the sound of children chanting tritonic taunts can still be heard in playgrounds in many parts of the world (ex. -

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

“Choosing an Influence, Or Bach the Inexhaustible: the Heterophony of the Voices of Twentieth- Century Composers”

Min-Ad: Israel Studies in Musicology Online, Vol. 13, 2015-16 Yulia Kreinin -“Choosing an Influence, or Bach the Inexhaustible: The Heterophony of the Voices of Twentieth- Century Composers” “Choosing an Influence, or Bach the Inexhaustible: The Heterophony of the Voices of Twentieth-Century Composers” YULIA KREININ Bach’s influence on posterity has been evident for over 250 years. In fact, since 1829, the year of Mendelssohn’s historic performance of the St. Matthew Passion, Bach has been one of the most respected figures in European musical culture. By the start of the twentieth century, Bach’s cultural presence was a given. Nevertheless, the twentieth century witnessed a new stage in the appreciation and understanding of Bach. In the first half of the century, “Back to Bach” was a significant motto for two waves of neoclassicism. From the 1960s on, Bach’s passion genre tradition was revived and reinterpreted, while other forms of homage to him blossomed (preludes and fugues, concerti grossi, works for solo strings). Composers’ spiritual dialogue with Bach took on a new importance. In this context, it is appropriate to investigate the reason(s) for the unique persistence of Bach’s influence into the twentieth century, an influence that surpasses that of other major composers of the past, including Mozart and Beethoven. Many scholars have addressed this conundrum; musicological research on Bach’s influence can be found in the four volumes of Bach und die Nachwelt (English, “Bach and Posterity”), published in Germany,1 and the seven volumes of Bach Perspectives, published in the United States.2 Nevertheless, “Why Bach?” has found only a partial answer and merits further examination. -

International Council for Traditional Music

PROMOTION. INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL FOR TRADITIONAL MUSIC Escola de Muska " SPONSORSHIP CAP ES 36,hWORLD·CONFERENCE, RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL, JULY 4-11 2001 The International Council for Traditional Music is a Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) in Formal Consultative Relations with UNESCO Fundacao Universitaria 1r Jose Bonifacio IDATErrIME IJuly 4 July 5 July II ROOM Salao 16:00 - 8:00 9:0010:30 Dourado PM Opening Welcome Ceremony Reception 11:00 - 12:30 Plenary Session: Samba Salao 2:30 - 4:00 9:0010:30 2:30- 6:00 ,yO 9:00-10:30 9:00-10:30 Pedro Panel: The Panel: Confronting the Open Meeting 'hey Have a Word for Music in New Contexts Panel-The Caiman politics of Past, Shaping the to ".txu What is "Music'? 11:00 - 12:30 Relationships between Experience Future.. Discuss Forms 12:30 Panel: The Censorship of Music: Researchers and the and ]]:00 - 12:30 of oClHuenting Garifuna Forms and Effects Communities They Study Interpretation.. Plenary Session Organization : Collaborative Efforts 2:30 - 4:00 Panel 11:00-12:30 2:30 - 4:00 and n ~esearchers and the Recent Ethno musicological Research in Music of the 4:30- 6:00 Panel: Interchange niry Research in Indigerious Societies Middle East and Beyond Panel: Shifting Ethnomusicologists among :OO!'9neJ from South American Lowlands 12:30 - 1:00 Contexts, and Independent Brazilians P(}p~Iaf Mu.sic in Indonesia.. _ part I Closing Session Changing Record Production in Studying 4:3Q26:OO fanel 4:30 - 6:00 Panel Roles: The Brazil and Beyond Traditional [email protected] ta the Source: Hispanic Recent Ethno musicological Relationships 4:30- 6:00 Music Mu~CfrGrn tbe Americas in the Research in Indigenous .. -

Counterpoint | Music | Britannica.Com

SCHOOL AND LIBRARY SUBSCRIBERS JOIN • LOGIN • ACTIVATE YOUR FREE TRIAL! Counterpoint & READ VIEW ALL MEDIA (6) VIEW HISTORY EDIT FEEDBACK Music Written by: Roland John Jackson $ ! " # Counterpoint, art of combining different melodic lines in a musical composition. It is among the characteristic elements of Western musical practice. The word counterpoint is frequently used interchangeably with polyphony. This is not properly correct, since polyphony refers generally to music consisting of two or more distinct melodic lines while counterpoint refers to the compositional technique involved in the handling of these melodic lines. Good counterpoint requires two qualities: (1) a meaningful or harmonious relationship between the lines (a “vertical” consideration—i.e., dealing with harmony) and (2) some degree of independence or individuality within the lines themselves (a “horizontal” consideration, dealing with melody). Musical theorists have tended to emphasize the vertical aspects of counterpoint, defining the combinations of notes that are consonances and dissonances, and prescribing where consonances and dissonances should occur in the strong and weak beats of musical metre. In contrast, composers, especially the great ones, have shown more interest in the horizontal aspects: the movement of the individual melodic lines and long-range relationships of musical design and texture, the balance between vertical and horizontal forces, existing between these lines. The freedoms taken by composers have in turn influenced theorists to revise their laws. The word counterpoint is occasionally used by ethnomusicologists to describe aspects of heterophony —duplication of a basic melodic line, with certain differences of detail or of decoration, by the various performers. This usage is not entirely appropriate, for such instances as the singing of a single melody at parallel intervals (e.g., one performer beginning on C, the other on G) lack the truly distinct or separate voice parts found in true polyphony and in counterpoint. -

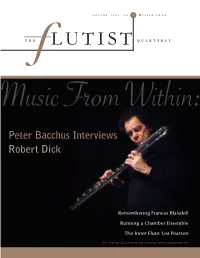

The Flutist Quarterly Volume Xxxv, N O

VOLUME XXXV , NO . 2 W INTER 2010 THE LUTI ST QUARTERLY Music From Within: Peter Bacchus Interviews Robert Dick Remembering Frances Blaisdell Running a Chamber Ensemble The Inner Flute: Lea Pearson THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION , INC :ME:G>:C8: I=: 7DA9 C:L =:69?D>CI ;GDB E:6GA 6 8ji 6WdkZ i]Z GZhi### I]Z cZl 8Vadg ^h EZVgaÉh bdhi gZhedch^kZ VcY ÓZm^WaZ ]ZVY_d^ci ZkZg XgZViZY# Djg XgV[ihbZc ^c ?VeVc ]VkZ YZh^\cZY V eZg[ZXi WaZcY d[ edlZg[ja idcZ! Z[[dgiaZhh Vgi^XjaVi^dc VcY ZmXZei^dcVa YncVb^X gVc\Z ^c dcZ ]ZVY_d^ci i]Vi ^h h^bean V _dn id eaVn# LZ ^ck^iZ ndj id ign EZVgaÉh cZl 8Vadg ]ZVY_d^ci VcY ZmeZg^ZcXZ V cZl aZkZa d[ jcbViX]ZY eZg[dgbVcXZ# EZVga 8dgedgVi^dc *). BZigdeaZm 9g^kZ CVh]k^aaZ! IC (,'&& -%%".),"(',* l l l # e Z V g a [ a j i Z h # X d b Table of CONTENTS THE FLUTIST QUARTERLY VOLUME XXXV, N O. 2 W INTER 2010 DEPARTMENTS 5 From the Chair 51 Notes from Around the World 7 From the Editor 53 From the Program Chair 10 High Notes 54 New Products 56 Reviews 14 Flute Shots 64 NFA Office, Coordinators, 39 The Inner Flute Committee Chairs 47 Across the Miles 66 Index of Advertisers 16 FEATURES 16 Music From Within: An Interview with Robert Dick by Peter Bacchus This year the composer/musician/teacher celebrates his 60th birthday. Here he discusses his training and the nature of pedagogy and improvisation with composer and flutist Peter Bacchus. -

Intraoral Pressure in Ethnic Wind Instruments

Intraoral Pressure in Ethnic Wind Instruments Clinton F. Goss Westport, CT, USA. Email: [email protected] ARTICLE INFORMATION ABSTRACT Initially published online: High intraoral pressure generated when playing some wind instruments has been December 20, 2012 linked to a variety of health issues. Prior research has focused on Western Revised: August 21, 2013 classical instruments, but no work has been published on ethnic wind instruments. This study measured intraoral pressure when playing six classes of This work is licensed under the ethnic wind instruments (N = 149): Native American flutes (n = 71) and smaller Creative Commons Attribution- samples of ethnic duct flutes, reed instruments, reedpipes, overtone whistles, and Noncommercial 3.0 license. overtone flutes. Results are presented in the context of a survey of prior studies, This work has not been peer providing a composite view of the intraoral pressure requirements of a broad reviewed. range of wind instruments. Mean intraoral pressure was 8.37 mBar across all ethnic wind instruments and 5.21 ± 2.16 mBar for Native American flutes. The range of pressure in Native American flutes closely matches pressure reported in Keywords: Intraoral pressure; Native other studies for normal speech, and the maximum intraoral pressure, 20.55 American flute; mBar, is below the highest subglottal pressure reported in other studies during Wind instruments; singing. Results show that ethnic wind instruments, with the exception of ethnic Velopharyngeal incompetency reed instruments, have generally lower intraoral pressure requirements than (VPI); Intraocular pressure (IOP) Western classical wind instruments. This implies a lower risk of the health issues related to high intraoral pressure. -

A Performance Guide to Selected Piano Solo Works Of

A PERFORMANCE GUIDE TO SELECTED PIANO SOLO WORKS OF LISAN WANG A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF ARTS BY TAO HE DISSERTATION ADVISORS: DR. BRETT CLEMENT DR. JAMES HELTON BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2020 Acknowledgements As this dissertation finally reaches completion, I wish to express gratitude to those who gave me their unreserved support. First, I would like to thank my mentors: I have received careful guidance from Dr. James Helton, my piano performance instructor. I admire his profound knowledge and rigorous scholarship. Without his help, I would not have been able to achieve my current level of musicianship and knowledge. I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Mei Zhong, my vocal performance professor. She led me into a whole new field, expanded my career, and inspired my potential. I would like to thank Dr. Brett Clement for always providing me help, advice, and insight throughout this entire dissertation process. I want to express gratitude to my family. To my parents and wife, thank you for your dedication, full support, and endurance for undertaking the many years I have spent away from home. I would like to offer the greatest blessing to my adorable son and daughter who are the motivation and spiritual pillar of my hard work! I would like to thank all of my friends who cared for and helped me. My special thanks go to Phillip Michael Blaine for his great assistance and strong support. He is one of my most trustworthy friends. -

2018 Available in Carbon Fibre

NFAc_Obsession_18_Ad_1.pdf 1 6/4/18 3:56 PM Brannen & LaFIn Come see how fast your obsession can begin. C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Booth 301 · brannenutes.com Brannen Brothers Flutemakers, Inc. HANDMADE CUSTOM 18K ROSE GOLD TRY ONE TODAY AT BOOTH #515 #WEAREVQPOWELL POWELLFLUTES.COM Wiseman Flute Cases Compact. Strong. Comfortable. Stylish. And Guaranteed for life. All Wiseman cases are hand- crafted in England from the Visit us at finest materials. booth 408 in All instrument combinations the exhibit hall, supplied – choose from a range of lining colours. Now also NFA 2018 available in Carbon Fibre. Orlando! 00 44 (0)20 8778 0752 [email protected] www.wisemanlondon.com MAKE YOUR MUSIC MATTER Longy has created one of the most outstanding flute departments in the country! Seize the opportunity to study with our world-class faculty including: Cobus du Toit, Antero Winds Clint Foreman, Boston Symphony Orchestra Vanessa Breault Mulvey, Body Mapping Expert Sergio Pallottelli, Flute Faculty at the Zodiac Music Festival Continue your journey towards a meaningful life in music at Longy.edu/apply TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the President ................................................................... 11 Officers, Directors, Staff, Convention Volunteers, and Competition Committees ................................................................ 14 From the Convention Program Chair ................................................. 21 2018 Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished Service Awards ........ 22 Previous Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished -

WOODWIND INSTRUMENT 2,151,337 a 3/1939 Selmer 2,501,388 a * 3/1950 Holland

United States Patent This PDF file contains a digital copy of a United States patent that relates to the Native American Flute. It is part of a collection of Native American Flute resources available at the web site http://www.Flutopedia.com/. As part of the Flutopedia effort, extensive metadata information has been encoded into this file (see File/Properties for title, author, citation, right management, etc.). You can use text search on this document, based on the OCR facility in Adobe Acrobat 9 Pro. Also, all fonts have been embedded, so this file should display identically on various systems. Based on our best efforts, we believe that providing this material from Flutopedia.com to users in the United States does not violate any legal rights. However, please do not assume that it is legal to use this material outside the United States or for any use other than for your own personal use for research and self-enrichment. Also, we cannot offer guidance as to whether any specific use of any particular material is allowed. If you have any questions about this document or issues with its distribution, please visit http://www.Flutopedia.com/, which has information on how to contact us. Contributing Source: United States Patent and Trademark Office - http://www.uspto.gov/ Digitizing Sponsor: Patent Fetcher - http://www.PatentFetcher.com/ Digitized by: Stroke of Color, Inc. Document downloaded: December 5, 2009 Updated: May 31, 2010 by Clint Goss [[email protected]] 111111 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 US007563970B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,563,970 B2 Laukat et al. -

The Ryukyuanist a Newsletter on Ryukyu/Okinawa Studies No

The Ryukyuanist A Newsletter on Ryukyu/Okinawa Studies No. 67 Spring 2005 This issue offers further comments on Hosei University’s International Japan-Studies and the role of Ryukyu/Okinawa in it. (For a back story of this genre of Japanese studies, see The Ryukyuanist No. 65.) We then celebrate Professor Robert Garfias’s achievements in ethnomusicology, for which he was honored with the Japanese government’s Order of the Rising Sun. Lastly, Publications XLVIII Hosei University’s Kokusai Nihongaku (International Japan-Studies) and the Ryukyu/Okinawa Factor “Meta science” of Japanese studies, according to the Hosei usage of the term, means studies of non- Japanese scholars’ studies of Japan. The need for such endeavors stems from a shared realization that studies of Japan by Japanese scholars paying little attention to foreign studies of Japan have produced wrong images of “Japan” and “the Japanese” such as ethno-cultural homogeneity of the Japanese inhabiting a certain immutable space since times immemorial. New images now in formation at Hosei emphasize Japan’s historical “internationality” (kokusaisei), ethno-cultural and regional diversity, fungible boundaries, and demographic changes. In addition to the internally diverse Yamato Japanese, there are Ainu and Ryukyuans/Okinawans with their own distinctive cultures. Terms like “Japan” and “the Japanese” have to be inclusive enough to accommodate the evolution of such diversities over time and space. Hosei is a Johnny-come-lately in the field of Japanese studies (Hosei scholars prefer -

“PRESENCE” of JAPAN in KOREA's POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Ju

TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Jung M.A. in Ethnomusicology, Arizona State University, 2001 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2007 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Eun-Young Jung It was defended on April 30, 2007 and approved by Richard Smethurst, Professor, Department of History Mathew Rosenblum, Professor, Department of Music Andrew Weintraub, Associate Professor, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung, Professor, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Eun-Young Jung 2007 iii TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE Eun-Young Jung, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Korea’s nationalistic antagonism towards Japan and “things Japanese” has mostly been a response to the colonial annexation by Japan (1910-1945). Despite their close economic relationship since 1965, their conflicting historic and political relationships and deep-seated prejudice against each other have continued. The Korean government’s official ban on the direct import of Japanese cultural products existed until 1997, but various kinds of Japanese cultural products, including popular music, found their way into Korea through various legal and illegal routes and influenced contemporary Korean popular culture. Since 1998, under Korea’s Open- Door Policy, legally available Japanese popular cultural products became widely consumed, especially among young Koreans fascinated by Japan’s quintessentially postmodern popular culture, despite lingering resentments towards Japan.