Malnutrition in Zambia Harnessing Social Protection for the Most Vulnerable

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zambia 30 September 2017

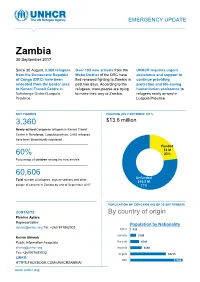

EMERGENCY UPDATE Zambia 30 September 2017 Since 30 August, 3,360 refugees Over 100 new arrivals from the UNHCR requires urgent from the Democratic Republic Moba District of the DRC have assistance and support to of Congo (DRC) have been fled renewed fighting to Zambia in continue providing relocated from the border area past two days. According to the protection and life-saving to Kenani Transit Centre in refugees, more people are trying humanitarian assistance to Nchelenge District/Luapula to make their way to Zambia. refugees newly arrived in Province. Luapula Province. KEY FIGURES FUNDING (AS 2 OCTOBER 2017) 3,360 $13.6 million requested for Zambia operation Newly-arrived Congolese refugees in Kenani Transit Centre in Nchelenge, Luapula province. 2,063 refugees have been biometrically registered Funded $3 M 60% 23% Percentage of children among the new arrivals Unfunded XX% 60,606 [Figure] M Unfunded Total number of refugees, asylum-seekers and other $10.5 M people of concern in Zambia by end of September 2017 77% POPULATION OF CONCERN (AS OF 30 SEPTEMBER) CONTACTS By country of origin Pierrine Aylara Representative Population by Nationality [email protected] Tel: +260 977862002 Other 415 Somalia 3199 Kelvin Shimoh Public Information Associate Burundi 4749 [email protected] Rwanda 6130 Tel: +260979585832 Angola 18715 LINKS: DRC 27398 HTTPS:FACEBOOK.COM/UNHCRZAMBIA/ www.unhcr.org 1 EMERGENCY UPDATE > Zambia / 30 September 2017 Emergency Response Luapula province, northern Zambia Since 30 August, over 3,000 asylum-seekers from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have crossed into northern Zambia. New arrivals are reportedly fleeing insecurity and clashes between Congolese security forces FARDC and a local militia groups in towns of Pweto, Manono, Mitwaba (Haut Katanga Province) as well as in Moba and Kalemie (Tanganyika Province). -

Fostering Accountability and Transparency (FACT) in Zambia Quarterly Report

Fostering Accountability and Transparency (FACT) in Zambia Quarterly Report January 1 to March 30, 2019 Youth Symposium Participants Outside FQM Trident Foundation Limited Offices after receiving training from one of FACT partners Submission Date: April 30, 2019 Submitted by: Chilufya Kasutu Agreement Number: Chief of Party AID-611-14-L-00001 Counterpart International, Zambia Email: [email protected] Submitted to: Edward DeMarco, USAID Zambia AOR This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development, Zambia (USAID/Zambia). It was prepared by Counterpart International. ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS AOR Agreement Officer’s Representative ART Anti-Retroviral Treatment CCAs Community Conservation Areas CCPs Community Conservation Plans CFGs Community Forest Groups CEFTA Citizens Engagement in Fostering Transparency and Accountability COMACO Community Markets for Conservation CRB Community Resource Boards CSPR Civil Society for Poverty Reduction CSO Civil Society Organization DAC District Advocacy Committee DAMI District Alternative Mining Indaba DDCC District Development Coordinating Committee DEBS District Education Board Secretary DHO District Health Office DIM District Integrated Meetings EITI Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative ESSP Education and Skills Sector Plan FACT Fostering Accountability and Transparency FZS Frankfurt Zoological Society GPE Global Partnership for Education GRZ Government of the Republic of Zambia HCC Health Centre Committee HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus LAG -

ZAMBIA HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT 1 January to 30 June 2018

UNICEF ZAMBIA HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT 1 January to 30 June 2018 Zambia Humanitarian Situation Report ©UNICEF Zambia/2017/Ayisi ©UNICEF REPORTING PERIOD: JANUARY - JUNE 2018 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights 15,425 # of registered refugees in Nchelengue • As of 28 June 2018, a total of 15,425 refugees from the district Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) were registered at (UNHCR, Infographic 28 June 2018) Kenani transit centre in the Luapula Province of Zambia. • UNICEF and partners are supporting the Government of Zambia 79% to provide life-saving services for all the refugees in Kenani of registered refugees are women and transit centre and in the Mantapala permanent settlement area. children • More than half of the refugees have been relocated to Mantapala permanent settlement area. 25,000 • The set-up of basic services in Mantapala is drastically delayed # of expected new refugees from DRC in due to heavy rainfall that has made access roads impassable. Nchelengue District in 2018 • Discussions between UNICEF and the Government are under way to develop a transition and sustainability plan to ensure the US$ 8.8 million continuity of services in refugee hosting areas. UNICEF funding requirement UNICEF’s Response with Partners Funding Status 2018 UNICEF Sector Carry- forward Total Total amount: UNICEF Sector $0.2 m Funds received current Target Results* Target year: $2.5 m Results* Nutrition: # of children admitted for SAM 400 273 400 273 treatment Health: # of children vaccinated against 11,875 6,690 11,875 6,690 measles WASH: # of people provided with access to 15,000 9,253 25,000 15,425 Funding Gap: $6.1 m safe water =68% Child Protection: # of children receiving 5,500 3,657 9,000 4,668 psychosocial and/or other protection services Funds available include funding received for the current year as well as the carry-forward from the previous year. -

Fifty Years of the Kasempa District, Zambia 1964 – 2014 Change and Continuity

FIFTY YEARS OF THE KASEMPA DISTRICT, ZAMBIA 1964 – 2014 CHANGE AND CONTINUITY. A case study of the ups and downs within a remote rural Zambian region during the fifty years since Independence. A descriptive analysis of its demography, geography, infrastructure, agricultural practice and present and traditional cultural aspects, including an account on the traditional ceremony of the installation of regional Headmen and the role and functions of the Kaonde clan structure. Dick Jaeger, 2015 [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MAPS AND FIGURES...........................................................................................................3 PART I 4 PREFACE – A WORD OF THANKS.....................................................................................................4 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY......................................................................................................6 CHAPTER 1. DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGES.......................................................................................10 ZAMBIA.............................................................................................................................10 KASEMPA DISTRICT........................................................................................................10 CHAPTER 2. AGRICULTURE............................................................................................................12 INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................................12 -

Ecological Changes in the Zambezi River Basin This Book Is a Product of the CODESRIA Comparative Research Network

Ecological Changes in the Zambezi River Basin This book is a product of the CODESRIA Comparative Research Network. Ecological Changes in the Zambezi River Basin Edited by Mzime Ndebele-Murisa Ismael Aaron Kimirei Chipo Plaxedes Mubaya Taurai Bere Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa DAKAR © CODESRIA 2020 Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa Avenue Cheikh Anta Diop, Angle Canal IV BP 3304 Dakar, 18524, Senegal Website: www.codesria.org ISBN: 978-2-86978-713-1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage or retrieval system without prior permission from CODESRIA. Typesetting: CODESRIA Graphics and Cover Design: Masumbuko Semba Distributed in Africa by CODESRIA Distributed elsewhere by African Books Collective, Oxford, UK Website: www.africanbookscollective.com The Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA) is an independent organisation whose principal objectives are to facilitate research, promote research-based publishing and create multiple forums for critical thinking and exchange of views among African researchers. All these are aimed at reducing the fragmentation of research in the continent through the creation of thematic research networks that cut across linguistic and regional boundaries. CODESRIA publishes Africa Development, the longest standing Africa based social science journal; Afrika Zamani, a journal of history; the African Sociological Review; Africa Review of Books and the Journal of Higher Education in Africa. The Council also co- publishes Identity, Culture and Politics: An Afro-Asian Dialogue; and the Afro-Arab Selections for Social Sciences. -

Determinants of Spatio Temporal Variability of Water Quality in The

© University of Hamburg 2018 All rights reserved Klaus Hess Publishers Göttingen & Windhoek www.k-hess-verlag.de ISBN: 978-3-933117-95-3 (Germany), 978-99916-57-43-1 (Namibia) Language editing: Will Simonson (Cambridge), and Proofreading Pal Translation of abstracts to Portuguese: Ana Filipa Guerra Silva Gomes da Piedade Page desing & layout: Marit Arnold, Klaus A. Hess, Ria Henning-Lohmann Cover photographs: front: Thunderstorm approaching a village on the Angolan Central Plateau (Rasmus Revermann) back: Fire in the miombo woodlands, Zambia (David Parduhn) Cover Design: Ria Henning-Lohmann ISSN 1613-9801 Printed in Germany Suggestion for citations: Volume: Revermann, R., Krewenka, K.M., Schmiedel, U., Olwoch, J.M., Helmschrot, J. & Jürgens, N. (eds.) (2018) Climate change and adaptive land management in southern Africa – assessments, changes, challenges, and solutions. Biodiversity & Ecology, 6, Klaus Hess Publishers, Göttingen & Windhoek. Articles (example): Archer, E., Engelbrecht, F., Hänsler, A., Landman, W., Tadross, M. & Helmschrot, J. (2018) Seasonal prediction and regional climate projections for southern Africa. In: Climate change and adaptive land management in southern Africa – assessments, changes, challenges, and solutions (ed. by Revermann, R., Krewenka, K.M., Schmiedel, U., Olwoch, J.M., Helmschrot, J. & Jürgens, N.), pp. 14–21, Biodiversity & Ecology, 6, Klaus Hess Publishers, Göttingen & Windhoek. Corrections brought to our attention will be published at the following location: http://www.biodiversity-plants.de/biodivers_ecol/biodivers_ecol.php Biodiversity & Ecology Journal of the Division Biodiversity, Evolution and Ecology of Plants, Institute for Plant Science and Microbiology, University of Hamburg Volume 6: Climate change and adaptive land management in southern Africa Assessments, changes, challenges, and solutions Edited by Rasmus Revermann1, Kristin M. -

St-Georges Platinum Enters Into an Agreement to Acquire Copper-Cobalt-Nickel Projects in the Zambian Copper Belt

ST-GEORGES PLATINUM ENTERS INTO AN AGREEMENT TO ACQUIRE COPPER-COBALT-NICKEL PROJECTS IN THE ZAMBIAN COPPER BELT Montreal, Quebec, February 5th, 2014 – St-Georges Platinum & Base Metals ltd (OTCQX: SXOOF) (CSE: SX) is pleased to announce that it has entered into a binding agreement to acquire 100% of two mineral mining projects in the Kasempa and Mwinilunga Districts in Western Zambia. Shongwa Project (Kasempa District) The Shongwa IOCG & Nickel project is located in Northwestern Zambia. The project area lies approximately 60km northwest of the town of Kasempa in northwest Zambia. The area is poorly developed with only minor trails away from the gravel Kasempa-Kaoma road link. The area consists of forested and relatively flat covered plains with some rolling hills and some permanent watercourses. Minor areas of habitation and subsistence farming exist to the south of Shongwa. The Large Scale Prospecting License (LPL) 14817-HQ-LPL covers an area of 726 square km. It was recently converted into 3 mining licenses covering the same total territory. The Shongwa project is the site of one of the oldest known deposits in Zambia dating back to the fourth century. Since the rediscovery of these ancient workings in 1899, the area has been mined intermittently for the recovery of high-grade copper ore. From 1903 until 1914, copper was recovered by underground mining of high-grade veins, followed by hand sorting and direct smelting. Mining activities terminated with the onset of World War 1. In 1952 further exploration and mine development commenced, with minimum production in 1956. Sulphide concentrate was also produced onsite from rich vein ore from lower mine levels utilizing a small concentrator. -

Post-Populism in Zambia: Michael Sata's Rise

This is the accepted version of the article which is published by Sage in International Political Science Review, Volume: 38 issue: 4, page(s): 456-472 available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512117720809 Accepted version downloaded from SOAS Research Online: http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/24592/ Post-populism in Zambia: Michael Sata’s rise, demise and legacy Alastair Fraser SOAS University of London, UK Abstract Models explaining populism as a policy response to the interests of the urban poor struggle to understand the instability of populist mobilisations. A focus on political theatre is more helpful. This article extends the debate on populist performance, showing how populists typically do not produce rehearsed performances to passive audiences. In drawing ‘the people’ on stage they are forced to improvise. As a result, populist performances are rarely sustained. The article describes the Zambian Patriotic Front’s (PF) theatrical insurrection in 2006 and its evolution over the next decade. The PF’s populist aspect had faded by 2008 and gradually disappeared in parallel with its leader Michael Sata’s ill-health and eventual death in 2014. The party was nonetheless electorally successful. The article accounts for this evolution and describes a ‘post-populist’ legacy featuring hyper- partisanship, violence and authoritarianism. Intolerance was justified in the populist moment as a reflection of anger at inequality; it now floats free of any programme. Keywords Elections, populism, political theatre, Laclau, Zambia, Sata, Patriotic Front Introduction This article both contributes to the thin theoretic literature on ‘post-populism’ and develops an illustrative case. It discusses the explosive arrival of the Patriotic Front (PF) on the Zambian electoral scene in 2006 and the party’s subsequent evolution. -

Socio-Economic Impact of Small Scale Emerald Mining on Local Community Livelihoods: the Case of Lufwanyama District

International Journal of Education and Research Vol. 3 No. 6 June 2015 SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACT OF SMALL SCALE EMERALD MINING ON LOCAL COMMUNITY LIVELIHOODS: THE CASE OF LUFWANYAMA DISTRICT Precious Moyo Shoko Precious Moyo Shoko has been graduate student studying for her MA in peace and conflict studies in the Dag Hammarskjöld Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies of the Copperbelt University. She specialised in environment and sustainable development for which this article is a part of her research output. She is the corresponding author. Her address is The Copperbelt University, DHIPS, P.O. Box 21692, Kitwe, Zambia, Mobile No: +260 977 674 743, Email: [email protected] Jacob Mwitwa Jacob Mwitwa is a Professor of natural resources management in the Copperbelt University in Zambia. He currently is in charge of Research and Innovation for the Copperbelt University. He has over 20 years of experience in natural resources management, environmental resources policy, rural livelihoods and conservation, and project management. He holds a PhD from the University of Stellenbosch and has published two books, and articles in peer-reviewed journals. His major research interest lie in resource rights and governance of environmental resources in the context of mining, climate change and protected area management. Professor Jacob Mwitwa contacts are School of Natural Resources, The Copperbelt University, P.O. Box 21692, Kitwe, Zambia, Mobile No: +260 977 848 462/966 848 462, Email: [email protected] Abstract Lufwanyama district has some of the world’s best emeralds and mining, is not contributing to the local economic development. Mining has failed to stimulate local enterprises, traditional industries and access to environmental resources. -

The Political Ecology of a Small-Scale Fishery, Mweru-Luapula, Zambia

Managing inequality: the political ecology of a small-scale fishery, Mweru-Luapula, Zambia Bram Verelst1 University of Ghent, Belgium 1. Introduction Many scholars assume that most small-scale inland fishery communities represent the poorest sections of rural societies (Béné 2003). This claim is often argued through what Béné calls the "old paradigm" on poverty in inland fisheries: poverty is associated with natural factors including the ecological effects of high catch rates and exploitation levels. The view of inland fishing communities as the "poorest of the poorest" does not imply directly that fishing automatically lead to poverty, but it is linked to the nature of many inland fishing areas as a common-pool resources (CPRs) (Gordon 2005). According to this paradigm, a common and open-access property resource is incapable of sustaining increasing exploitation levels caused by horizontal effects (e.g. population pressure) and vertical intensification (e.g. technological improvement) (Brox 1990 in Jul-Larsen et al. 2003; Kapasa, Malasha and Wilson 2005). The gradual exhaustion of fisheries due to "Malthusian" overfishing was identified by H. Scott Gordon (1954) and called the "tragedy of the commons" by Hardin (1968). This influential model explains that whenever individuals use a resource in common – without any form of regulation or restriction – this will inevitably lead to its environmental degradation. This link is exemplified by the prisoner's dilemma game where individual actors, by rationally following their self-interest, will eventually deplete a shared resource, which is ultimately against the interest of each actor involved (Haller and Merten 2008; Ostrom 1990). Summarized, the model argues that the open-access nature of a fisheries resource will unavoidably lead to its overexploitation (Kraan 2011). -

FORM #3 Grants Solicitation and Management Quarterly

FORM #3 Grants Solicitation and Management Quarterly Progress Report Grantee Name: Maternal and Child Survival Program Grant Number: # AID-OAA-A-14-00028 Primary contact person regarding this report: Mira Thompson ([email protected]) Reporting for the quarter Period: Year 3, Quarter 1 (October –December 2018) 1. Briefly describe any significant highlights/accomplishments that took place during this reporting period. Please limit your comments to a maximum of 4 to 6 sentences. During this reporting period, MCSP Zambia: Supported MOH to conduct a data quality assessment to identify and address data quality gaps that some districts have been recording due to inability to correctly interpret data elements in HMIS tools. Some districts lacked the revised registers as well. Collected data on Phase 2 of the TA study looking at the acceptability, level of influence, and results of MCSP’s TA model that supports the G2G granting mechanism. Data collection included interviews with 53 MOH staff from 4 provinces, 20 districts and 20 health facilities. Supported 16 districts in mentorship and service quality assessment (SQA) to support planning and decision-making. In the period under review, MCSP established that multidisciplinary mentorship teams in 10 districts in Luapula Province were functional. Continued with the eIMCI/EPI course orientation in all Provinces. By the end of the quarter under review, in Muchinga 26 HCWs had completed the course, increasing the number of HCWs who improved EPI knowledge and can manage children using IMNCI Guidelines. In Southern Province, 19 mentors from 4 districts were oriented through the electronic EPI/IMNCI interactive learning and had the software installed on their computers. -

Ministry of Health Provincial Health Office, Northwestern Province

REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA MINISTRY OF HEALTH PROVINCIAL HEALTH OFFICE, NORTHWESTERN PROVINCE REPORT ON LONG LASTING INSECTICIDE NETS MASS DISTRIBUTION CAMPAIGN 2017 COMPILED BY NSOFWA FRANCIS CHIEF ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH OFFICER NORTH WESTERN PROVINCE 1 Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 2 2.0 MAIN OBJECTIVE AND MASS CAMPAIGN STRATEGY .................... 4 3.0 STAGES OF THE CAMPAIGN ........................................................... 4 3.1 PLANNING AND PREPARATORY STAGE .......................................... 5 3.2 HOUSEHOLD REGISTRATION, DATA ENTRY AND DATA VALIDATION 5 3.2.1 MOBILIZATION AND SENSITIZATION ........................................... 6 3.3 DISTRIBUTION METHODS .............................................................. 6 4.0 SUCCESSES ................................................................................. 16 5.0 CHALLENGES .............................................................................. 16 6.0 LESSONS LEARNT ....................................................................... 17 7.0 RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................... 17 8.0 CONCLUSION ............................................................................... 18 1 2 1.0 INTRODUCTION North-Western Province is one of the ten Provinces of Zambia. The Province has a total of eleven Districts that is: Solwezi (provincial capital), Chavuma, Zambezi, Kabompo, Mwinilunga, Mufumbwe, Kasempa, Ikelengi, Manyinga, kalumbila