Practical Approaches for Producing Inexpensive Digital Photography in the Dermatology Office Part One

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Photography and Video Policy: to Govern Clinical and Non-Clinical Recordings

PAT/PA 14 v.4 Photography and Video Policy: to Govern Clinical and Non-clinical Recordings This procedural document supersedes: PAT/PA 14 v.3 – Photography and Video Policy: to Govern Clinical and Non-clinical Recordings Did you print this document yourself? The Trust discourages the retention of hard copies of policies and can only guarantee that the policy on the Trust website is the most up-to-date version. If, for exceptional reasons, you need to print a policy off, it is only valid for 24 hours. Author/reviewer: (this Tim Vernon - Head of Medical Photography and version) Graphic Design Roy Underwood - Head of Information Governance & Registration Authority Manager Date written/revised: 20.08.2013 Approved by: Information Governance Group Date of approval: 09 September 2013 Date issued: 12 November 2013 Next review date: 09 September 2016 Target audience: Trust-wide Page 1 of 32 PAT/PA 14 v.4 Amendment Form Please record brief details of the changes made alongside the next version number. If the procedural document has been reviewed without change, this information will still need to be recorded although the version number will remain the same. Version Date Brief Summary of Changes Author Issued Version 4 12 Nov • Amendment to section 5.3 - about the Tim Vernon 2013 copyright of images found on the Internet • Amendment to section 5.5 - about the registration of photography & video equipment with MPGD and its safe storage. Version 3 November • Reformatted to meet new style format Tim Vernon 2012 as per Trust policy CORP/COMM 1 • References updated • Appendices updated and re-designed • Appendix 4 and 5 added Version 2 January ‘Dolphin Imaging System in Orthodontics’ Tim Vernon (minor 2012 added to section 10. -

Page 16 of 128 Exhibit No. Description Deposition

Case 1:04-cv-01373-KAJ Document 467-2 Filed 10/23/2006 Page 1 of 140 Exhibit Description Deposition Objections No. Ex. No. PTX-168 7/16/2003, Technical Reference Napoli Ex. Manual [DM270] (EKCCCI007053- 132 836) PTX-169 2003, Data Sheet for TMS320DM270 Processor (AX200153-55) PTX-170 10/30/2002, DM270 Preliminary Napoli Ex. Register Manual Rev. b0.6 131 (EKCCCI001305-495) PTX-171 TI DM270 Imx Hardware Akiyama Programming Interface, Version 0.0 Ex. 312 (EKCNYII005007249-260) PTX-172 3/3/2003, DM270 Preliminary Data Ohtake Ex. Sheet Rev. b0.7C (EKCCCI008094- 123 131) PTX-173 Fact Sheet for TMS320DM270 Lacks Processor (AX200150-52) authenticity; Hearsay; Lacks foundation; Lacks relevance PTX-174 6/04, Data Sheet rev 0.5 for Hynix Ligler Ex. Lacks HY57V561620C[L]T[P] (AX200163- 13 (ITC) authenticity; 74) Hearsay; Lacks foundation; Lacks relevance PTX-175 Sharp RJ21T3AA0PT Data Sheet Hearsay; (EKCCCI017389-413) Lacks foundation; Lacks relevance PTX-176 DX7630 Thumbnail Test Lacks (AXD022568-81) authenticity; Hearsay; Lacks foundation; Lacks relevance; Inaccurate/ incomplete description PTX-177 1/11/2005, DM270 IP Chain ver. 0.7 Yoshikawa with translation (EKC001021025-31, Ex. 348 AX211033-42) PTX-178 1/26/2004, Bud Camera F/W Task Lacks foundation; Interface Capture Main <-> Image ISR Lacks relevance (DX7630) ver. 0.07 / Takeshi Domen with translation (EKCCCI002404-19, AX211607-26) Page 16 of 128 Case 1:04-cv-01373-KAJ Document 467-2 Filed 10/23/2006 Page 2 of 140 Exhibit Description Deposition Objections No. Ex. No. PTX-179 2/17/2003, Budweiser Camera EXIF Akiyama Lacks foundation; File Access Library Spec (DX7630) Ex. -

Are You Ready for a Digital Camera? by Jennifer Ruisaard and Conrad Turner

Are You Ready for a Digital Camera? by Jennifer Ruisaard and Conrad Turner Digital cameras flashed onto the technology scene a few years ago, threatening the future of conventional photography. Employing the same elements as traditional cameras, digital cameras convert images into a series of pixels that computers can understand and display directly on-screen. These digital images transmit easily through e-mail attachments and are instantly ready to use. The quality of digital images improved drastically over the last five years. In addition, digital cameras offer the benefits of speed, flexibility, and cost savings. Digital photographs are easy to retouch and manipulate through programs such as Photoshop. Furthermore, digital images do not need to be scanned. Therefore, defects introduced by the scanning process are eliminated. Types of Digital Cameras The digital photography market offers consumers three types of cameras: low-, mid-, and high-range. Buyers of digital cameras should choose a camera depending on their specific needs and the type of job to be done. Low-end digital cameras cost around $1,000 and are equivalent to conventional point-and- shoot cameras. Their low resolution, usually about 640 ´ 480 pixels, makes them a cost-effective tool for jobs that do not require high quality, sharpness, or color accuracy. This range of cameras can produce quality prints up to 2.4 ´ 1.8 inches at 133 lpi (266 ppi), which is sufficient for small brochures, advertisements, and catalog images. The next group of digital cameras, called mid-range, cost between $5,000 and $15,000. These cameras are essentially traditional Single Lens Reflex (SLR) camera bodies. -

Openimageio 1.7 Programmer Documentation (In Progress)

OpenImageIO 1.7 Programmer Documentation (in progress) Editor: Larry Gritz [email protected] Date: 31 Mar 2016 ii The OpenImageIO source code and documentation are: Copyright (c) 2008-2016 Larry Gritz, et al. All Rights Reserved. The code that implements OpenImageIO is licensed under the BSD 3-clause (also some- times known as “new BSD” or “modified BSD”) license: Redistribution and use in source and binary forms, with or without modification, are per- mitted provided that the following conditions are met: • Redistributions of source code must retain the above copyright notice, this list of condi- tions and the following disclaimer. • Redistributions in binary form must reproduce the above copyright notice, this list of con- ditions and the following disclaimer in the documentation and/or other materials provided with the distribution. • Neither the name of the software’s owners nor the names of its contributors may be used to endorse or promote products derived from this software without specific prior written permission. THIS SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED BY THE COPYRIGHT HOLDERS AND CONTRIB- UTORS ”AS IS” AND ANY EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY AND FIT- NESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE ARE DISCLAIMED. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE COPYRIGHT OWNER OR CONTRIBUTORS BE LIABLE FOR ANY DIRECT, INDIRECT, INCIDENTAL, SPECIAL, EXEMPLARY, OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES (INCLUD- ING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, PROCUREMENT OF SUBSTITUTE GOODS OR SERVICES; LOSS OF USE, DATA, OR PROFITS; OR BUSINESS INTERRUPTION) HOWEVER CAUSED AND ON ANY THEORY OF LIABILITY, WHETHER IN CONTRACT, STRICT LIABIL- ITY, OR TORT (INCLUDING NEGLIGENCE OR OTHERWISE) ARISING IN ANY WAY OUT OF THE USE OF THIS SOFTWARE, EVEN IF ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGE. -

Graphicconverter 6.6

User’s Manual GraphicConverter 6.6 Programmed by Thorsten Lemke Manual by Hagen Henke Sales: Lemke Software GmbH PF 6034 D-31215 Peine Tel: +49-5171-72200 Fax:+49-5171-72201 E-mail: [email protected] In the PDF version of this manual, you can click the page numbers in the contents and index to jump to that particular page. © 2001-2009 Elbsand Publishers, Hagen Henke. All rights reserved. www.elbsand.de Sales: Lemke Software GmbH, PF 6034, D-31215 Peine www.lemkesoft.com This book including all parts is protected by copyright. It may not be reproduced in any form outside of copyright laws without permission from the author. This applies in parti- cular to photocopying, translation, copying onto microfilm and storage and processing on electronic systems. All due care was taken during the compilation of this book. However, errors cannot be completely ruled out. The author and distributors therefore accept no responsibility for any program or documentation errors or their consequences. This manual was written on a Mac using Adobe FrameMaker 6. Almost all software, hardware and other products or company names mentioned in this manual are registered trademarks and should be respected as such. The following list is not necessarily complete. Apple, the Apple logo, and Macintosh are trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries. Mac and the Mac OS logo are trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc. Photo CD mark licensed from Kodak. Mercutio MDEF copyright Ramon M. Felciano 1992- 1998 Copyright for all pictures in manual and on cover: Hagen Henke except for page 95 exa- mple picture Tayfun Bayram and others from www.photocase.de; page 404 PCD example picture © AMUG Arizona Mac Users Group Inc. -

CODE by R.Mutt

CODE by R.Mutt dcraw.c 1. /* 2. dcraw.c -- Dave Coffin's raw photo decoder 3. Copyright 1997-2018 by Dave Coffin, dcoffin a cybercom o net 4. 5. This is a command-line ANSI C program to convert raw photos from 6. any digital camera on any computer running any operating system. 7. 8. No license is required to download and use dcraw.c. However, 9. to lawfully redistribute dcraw, you must either (a) offer, at 10. no extra charge, full source code* for all executable files 11. containing RESTRICTED functions, (b) distribute this code under 12. the GPL Version 2 or later, (c) remove all RESTRICTED functions, 13. re-implement them, or copy them from an earlier, unrestricted 14. Revision of dcraw.c, or (d) purchase a license from the author. 15. 16. The functions that process Foveon images have been RESTRICTED 17. since Revision 1.237. All other code remains free for all uses. 18. 19. *If you have not modified dcraw.c in any way, a link to my 20. homepage qualifies as "full source code". 21. 22. $Revision: 1.478 $ 23. $Date: 2018/06/01 20:36:25 $ 24. */ 25. 26. #define DCRAW_VERSION "9.28" 27. 28. #ifndef _GNU_SOURCE 29. #define _GNU_SOURCE 30. #endif 31. #define _USE_MATH_DEFINES 32. #include <ctype.h> 33. #include <errno.h> 34. #include <fcntl.h> 35. #include <float.h> 36. #include <limits.h> 37. #include <math.h> 38. #include <setjmp.h> 39. #include <stdio.h> 40. #include <stdlib.h> 41. #include <string.h> 42. #include <time.h> 43. #include <sys/types.h> 44. -

Megaplus Conversion Lenses for Digital Cameras

Section2 PHOTO - VIDEO - PRO AUDIO Accessories LCD Accessories .......................244-245 Batteries.....................................246-249 Camera Brackets ......................250-253 Flashes........................................253-259 Accessory Lenses .....................260-265 VR Tools.....................................266-271 Digital Media & Peripherals ..272-279 Portable Media Storage ..........280-285 Digital Picture Frames....................286 Imaging Systems ..............................287 Tripods and Heads ..................288-301 Camera Cases............................302-321 Underwater Equipment ..........322-327 PHOTOGRAPHIC SOLUTIONS DIGITAL CAMERA CLEANING PRODUCTS Sensor Swab — Digital Imaging Chip Cleaner HAKUBA Sensor Swabs are designed for cleaning the CLEANING PRODUCTS imaging sensor (CMOS or CCD) on SLR digital cameras and other delicate or hard to reach optical and imaging sur- faces. Clean room manufactured KMC-05 and sealed, these swabs are the ultimate Lens Cleaning Kit in purity. Recommended by Kodak and Fuji (when Includes: Lens tissue (30 used with Eclipse Lens Cleaner) for cleaning the DSC Pro 14n pcs.), Cleaning Solution 30 cc and FinePix S1/S2 Pro. #HALCK .........................3.95 Sensor Swabs for Digital SLR Cameras: 12-Pack (PHSS12) ........45.95 KA-11 Lens Cleaning Set Includes a Blower Brush,Cleaning Solution 30cc, Lens ECLIPSE Tissue Cleaning Cloth. CAMERA ACCESSORIES #HALCS ...................................................................................4.95 ECLIPSE lens cleaner is the highest purity lens cleaner available. It dries as quickly as it can LCDCK-BL Digital Cleaning Kit be applied leaving absolutely no residue. For cleaing LCD screens and other optical surfaces. ECLIPSE is the recommended optical glass Includes dual function cleaning tool that has a lens brush on one side and a cleaning chamois on the other, cleaner for THK USA, the US distributor for cleaning solution and five replacement chamois with one 244 Hoya filters and Tokina lenses. -

Farewell to the Kodak DCS Dslrs

John Henshall’s Chip Shop FAREWELL TO THE KODAK DCS John Henshall looks at Kodak’s legacy as the end of its DSLR production is announced . hen Kodak introduced the the world’s first totally portable Digital W Camera System – the DCS – in 1991 it established Eastman Kodak as the world leader of professional digital image capture. Fourteen years later, Kodak has just announced that it is ending production 1992: DCS200 of Digital Single Lens Reflex cameras. The DCS was a product launched ahead of its potential market, but one which indelibly marked the start of the future of photography. Kodak was smart. It housed its DCS in something photographers were already at home with: a Nikon F3 camera body. All the F3’s functions were retained, and the DCS used standard Nikon lenses. Only the 1991: The original Kodak DCS [100] and DSU 2005: Last of the line – the DCS ProSLR/c focusing screen was changed. A new Kodak-produced digital The relative sensitivity of the camera back was fixed to the Nikon F3 DCS camera back was ISO100. body. A light sensitive integrated circuit Exposure could be ‘pushed’ by – Charge Coupled Device – was fitted one, two or three ƒ-stops to into its film plane. ISO200, 400 or 800 on an This CCD image sensor had an individual shot-by-shot basis. incredible 1.3 million individual pixels It was not necessary to m o c . – more than four times as many as in expose a whole ‘roll of film’ at e r t n television cameras – arranged in a the same ISO rating, as was e c - i 1024 x 1280 pixel rectangle measuring necessary when shooting film. -

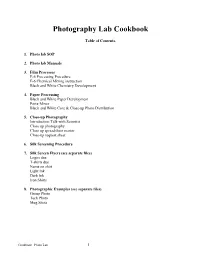

Photography Lab Cookbook

Photography Lab Cookbook Table of Contents. 1. Photo lab SOP 2. Photo lab Manuals 3. Film Processes E-6 Processing Procedure E-6 Chemical Mixing instruction Black and White Chemistry Development 4. Paper Processing Black and White Paper Development Porta-Mixer Black and White Core & Close-up Photo Distribution 5. Close-up Photography Introduction Talk with Scientist Close up photography Close up spreadsheet master Close-up request sheet 6. Silk Screening Procedure 7. Silk Screen Flyers (see separate files) Logos due T-shirts due Name on shirt Light Ink Dark Ink Iron Shirts 8. Photographic Examples (see separate files) Group Photo Tech Photo Mug Shots Cookbook– Photo Lab 1 PHOTO LAB STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURE (SOP) PORTCALL (on coming) Onboard ship: • Find off going Marine Lab Specialist’s, Photo Lab and begin X-over. X-over • Read lab reports from previous leg. • Discuss with off going marine specialist any changes in equipment status, software or procedures. • Check supply levels in photo lab and hold refer. You are responsible for this inventory. Estimate amount of film, paper and chemistry needed for each particular type of leg. If you do not feel you have enough supplies necessary (after checking oncoming shipments), notify LO to purchase film/paper/chemistry in port. • You are responsible for knowing the status of ALL equipment in your lab by the end of the x- over. If you need additional days to complete your x-over, notify the LO ASAP so that arrangements can be made. Other: • Assist with loading/unloading freight and other tasks as directed by LO/ALO. -

ASSESSING MEDICAL PHOTOGRAPHY EQUIPMENT a Guide to Available Technology and Its Potential Benefits

COVER FOCUS ASSESSING MEDICAL PHOTOGRAPHY EQUIPMENT A guide to available technology and its potential benefits. BY EMILY ALTEN Emily Alten is a writing enthusiast and biology nerd who specializes in educational healthcare and medicine content for RxPhoto. She is a Magna Cum Laude graduate from Columbia University with a degree in biological sciences/pre-medical studies. RxPhoto’s medical app converts an iPhone or an iPad into a clinical photography system securely capturing, managing, and sharing patient photos and videos. RxPhoto.com ithout a doubt, you need to take photos of your anatomical region. Most physicians set up a photography patients on a daily basis. Whether you’re building room specifically for using these types of cameras. a before and after portfolio for marketing or using photography for procedure tracking, you want MOBILE DEVICES Wyour pictures to look clean and consistent. Very few offices have Because of the upfront cost of the other options, it’s no a skilled photographer on staff, so it can be difficult to decide on surprise that many doctors are using mobile devices, such as the best camera to use. Ahead, we profile the pros and cons of tablets and smartphones, especially since the quality of mobile the three most common options for aesthetic photography. device cameras has been improving at a staggering pace. DSLR MOBILE DEVICES VERSUS DSLR Many physicians choose a DSLR camera for their clinical Smartphone and tablet cameras are often just as good, if photography, and most set up a dedicated photography not better, than standard point-and-shoot digital cameras. -

Hysteria in the Lens of Nineteenth Century Medical Photography

11 EXPOSURE, NEGATIVE, PROOF: HYSTERIA IN THE LENS OF NINETEENTHCENTURY MEDICAL PHOTOGRAPHY M ICHAEL P. V ICARO P ENNS YLVANIA STATE U NIVERS ITY—G REATER A LLEGHENY This article explores the role of photography in the and forcing things in the world to present themselves in cultural production of “hysteria” in the nineteenth-cen- a manner that could be seen, analyzed, and thereby con- tury, arguing that image-making technologies deeply trolled (Heidegger 1938). Photography, introduced into shaped public perceptions of deviance and normality. a flourishing culture of scientific empiricism, helped to Late nineteenth-century hysteria can be described as a satisfy and to amplify the desire for vantage points from uniquely “photogenic” ailment— literally produced and which one might witness and dutifully record without bias developed by the light of the camera flash. Art historians the magnitude and minutia of life (Peters 2005). In early have studied the photographic history of hysteria (Didi- texts, the processes of daguerreotypy and photography Huberman 2003; Koehler 2001; Schade 1995; Gilman were routinely called “discoveries” rather than “inventions,” 1982). But media scholars have largely ignored the way suggesting that they were natural phenomenon harnessed images of hysteria functioned as a series of visual argu- by human hands (Marien 2002). In Daguerre’s words, “the ments about the “normal” bourgeois, white, feminine body. daguerreotype is not an instrument which serves to draw Conversely, those whose work has situated hysteria in the nature; but a chemical and physical process which gives larger context of the formation of the modern body have her the power to reproduce herself ” (qtd. -

Digitális Fotokamerák

DIGITÁLIS FOTOKAMERÁK 2020 augusztus blzs ver. 1.1 TARTALOMJEGYZÉK 1. A digitális kameragyártás általános helyzete…………………………...3 2. Középformátum………………………………………………………...6 2.1 Hátfalak……………………………………………………………..9 2.2 Kamerák…………………………………………………………...18 3. Kisfilmes teljes képkockás formátum………………………………….21 3.1 Tükörreflexesek……………………………………………………22 3.2 Távmérősek………………………………………………………...31 3.3 Kompaktok…………………………………………………………33 3.4 Tükörnélküli cserélhető objektívesek………………………………35 4. APS-C formátum……………………………………………………….42 4.1 Tükörreflexesek…………………………………………………….43 4.2 Kompaktok………………………………………………………….50 4.3 Tükörnélküli cserélhető objektívesek……………………………….53 5. Mikro 4/3-os formátum…………………………………………………60 5.1 Olympus…………………………………………………………….61 5.2 Panasonic…………………………………………………………...64 6. „1 col”-os formátum……………………………………………………69 6.1 Cserélhető objektívesek…………………………………………….69 6.2 Beépített objektívesek………………………………………………71 7. „Nagyszenzoros” zoom-objektíves kompaktok………………………..75 8. „Kisszenzoros” zoom-objektíves kompaktok………………………….77 8.1 Bridge kamerák…………………………………………………….78 8.2 Utazó zoomos ( szuperzoomos ) kompaktok……………………….81 8.3 Strapabíró ( kaland- víz- ütés- porálló ) kompaktok………………..83 9. A kurrens kamerák összefoglalása……………………………………...87 9.1 Technológia szerint…………………………………………………87 9.2 Gyártók szerint……………………………………………………..89 10. Gyártók és rendszereik………………………………………………....90 10.1 Canon……………………………………………………………...91 10.2 Sony……………………………………………………………….94 10.3 Nikon……………………………………………………………...98 10.4 Olympus………………………………………………………….101 10.5 Panasonic………………………………………………………...104