Henry Darger: Life and Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darger, Henry (1892-1973) by Jim Elledge

Darger, Henry (1892-1973) by Jim Elledge Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2013 glbtq,Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Now considered one of the most original and important artists of the last half of the twentieth century, Henry Darger died completely unknown in his native Chicago. When he moved out of his one-room apartment on November 24, 1972 into an old folks home a few blocks away, his next door neighbor, who had been hired to clear out Darger's room, discovered over 300 canvases Darger had painted and the huge manuscripts of two novels and an autobiography that he had written. The canvases, which depict naked little girls with penises (who, in many of the paintings, are being eviscerated, strangled, and crucified by adults), became synonymous with the man, causing critics who were unaware of their relevance to the gay subculture of the time to call Darger a pedophile, child killer, and sadist. Darger's Life Darger was born into utter poverty on April 12, 1892. His mother died in childbirth when he was four. Within a few years, his father, a failed, alcoholic tailor, had all but abandoned his parental responsibilities to the boy. Growing up in one of the darkest and most desperate vice districts in Chicago, now Henry Darger. Photo by the much-gentrified Near West Side, Darger became involved in male-male sexual David Berglund, c. 1970. activities early in life, admitting to the most significant one in his autobiography decades later. In it, he reported that, by the time he was eight years old, he had developed a relationship with an adult guard whom he visited late at night at the lumberyard where the man worked. -

The Henry Darger Study Center at the American Folk Art Museum a Collections Policy Recommendation Report

The Henry Darger Study Center at the American Folk Art Museum A Collections Policy Recommendation Report by Shannon Robinson Spring 2010 I. Overview page 3 II. Mission and Goals page 5 III. Service Community and Programs page 7 IV. The Collection and Future Acquisition page 8 V. Library Selection page 11 VI. Responsibilities page 12 VII. Complaints and Censorship page 13 VIII. Evaluation page 13 IX. Bibliography page 15 X. Additional Materials References page 16 I. Overview The American Folk Art Museum in New York City is largely focused on the collection and preservation of the artwork of self-taught artists in the United States and abroad. The Museum began in 1961 as the Museum of Early American Folk Arts; at that time, the idea of appreciating folk art alongside contemporary art was a consequence of modernism (The American Folk Art Museum, 2010c). The collection’s pieces date to as early as the eighteenth century and in it’s earlier days was largely comprised of sculpture. The Museum approached collecting and exhibiting much like a contemporary art gallery. This was in support of its mission promoting the “aesthetic appreciation” and “creative expressions” of folk artists as parallel in content and quality to more mainstream, trained artists. (The American Folk Art Museum, 2010b). Within ten years of opening, however, and though the collection continued to grow, a financial strain hindered a bright future for the Museum. In 1977, the Museum’s Board of Trustees appointed Robert Bishop director (The American Folk Art Museum, 2010c). While Bishop was largely focused on financial and facility issues, he encouraged gift acquisitions, and increasing the collection in general, by promising many artworks from his personal collection. -

Accidental Genius

Accidental Genius Accidental Genius ART FROM THE ANTHONY PETULLO COLLECTION Margaret Andera Lisa Stone with an introduction by Jane Kallir Milwaukee Art Museum DelMonico Books Prestel MUNICH LONDON NEW YORK CONTENTS 19 FOREWORD Daniel T. Keegan 21 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Margaret Andera 23 Art Brut and “Outsider” Art A Changing Landscape Jane Kallir 29 “It’s a picture already” The Anthony Petullo Collection Lisa Stone 45 PLATES 177 THE ANTHONY PETULLO COLLECTION 199 BIOGRAPHIES OF THE ARTISTS !" FOREWORD Daniel T. KeeganDirector, Milwaukee Art Museum The Milwaukee Art Museum is pleased to present Accidental Genius: the Roger Brown Study Collection at the School of the Art Institute Art from the Anthony Petullo Collection, an exhibition that celebrates of Chicago, for her insightful essay for this publication. the gift to the Museum of Anthony Petullo’s collection of modern A project of this magnitude would not have been possible self-taught art. Comprising more than three hundred artworks, the without generous financial support. The Milwaukee Art Museum collection is the most extensive grouping of its kind in any American wishes to thank the Anthony Petullo Foundation; Leslie Hindman, museum or in private hands. Thanks to this gift, the Milwaukee Art Inc.; the Einhorn Family Foundation; and Friends of Art, a support Museum’s holdings now encompass a broadly inclusive represen- group of the Museum, for sponsoring the exhibition. Tony Petullo tation of self-taught art as an international phenomenon. is a past president of Friends of Art, and he credits the group for Tony Petullo, a retired Milwaukee businessman, built his col- introducing him to collecting. -

Art-Related Archival Materials in the Chicago Area

ART-RELATED ARCHIVAL MATERIALS IN THE CHICAGO AREA Betty Blum Archives of American Art American Art-Portrait Gallery Building Smithsonian Institution 8th and G Streets, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20560 1991 TRUSTEES Chairman Emeritus Richard A. Manoogian Mrs. Otto L. Spaeth Mrs. Meyer P. Potamkin Mrs. Richard Roob President Mrs. John N. Rosekrans, Jr. Richard J. Schwartz Alan E. Schwartz A. Alfred Taubman Vice-Presidents John Wilmerding Mrs. Keith S. Wellin R. Frederick Woolworth Mrs. Robert F. Shapiro Max N. Berry HONORARY TRUSTEES Dr. Irving R. Burton Treasurer Howard W. Lipman Mrs. Abbott K. Schlain Russell Lynes Mrs. William L. Richards Secretary to the Board Mrs. Dana M. Raymond FOUNDING TRUSTEES Lawrence A. Fleischman honorary Officers Edgar P. Richardson (deceased) Mrs. Francis de Marneffe Mrs. Edsel B. Ford (deceased) Miss Julienne M. Michel EX-OFFICIO TRUSTEES Members Robert McCormick Adams Tom L. Freudenheim Charles Blitzer Marc J. Pachter Eli Broad Gerald E. Buck ARCHIVES STAFF Ms. Gabriella de Ferrari Gilbert S. Edelson Richard J. Wattenmaker, Director Mrs. Ahmet M. Ertegun Susan Hamilton, Deputy Director Mrs. Arthur A. Feder James B. Byers, Assistant Director for Miles Q. Fiterman Archival Programs Mrs. Daniel Fraad Elizabeth S. Kirwin, Southeast Regional Mrs. Eugenio Garza Laguera Collector Hugh Halff, Jr. Arthur J. Breton, Curator of Manuscripts John K. Howat Judith E. Throm, Reference Archivist Dr. Helen Jessup Robert F. Brown, New England Regional Mrs. Dwight M. Kendall Center Gilbert H. Kinney Judith A. Gustafson, Midwest -

The New York Times the Outsider Fair Made Art 'Big' Again

The Outsider Fair Made Art ‘Big’ Again By ROBERTA SMITH JAN. 19, 2017 One of Morton Bartlett’s half-size anatomically correct prepubescent girls from 1950. Morton Bartlett, Marion Harris New York’s Outsider Art Fair, which opened Thursday, is celebrating its 25th anniversary. It made its debut in 1993 in the 19th-century Puck Building in SoHo’s northeast corner. I saw the first iteration, reviewed the second and wrote about it many times after that. I enjoy most art fairs for their marathon-like density of visual experience and information, but the Outsider fair quickly became my favorite. It helped make art big again. An untitled painting by Henry Darger of his intrepid Vivian Girls. 2017 Henry Darger/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Andrew Edlin Gallery The focus of the fair, according to its founder, Sanford L. Smith, known as Sandy, was the work of outsider artists, a catchall phrase for many kinds of self-taught creators. (Mr. Smith credited the phrase to Roger Cardinal, the art historian and author of “Outsider Art,” published in 1972.) Outsider work connoted a certain purity — an unstoppable need to make art that was unsullied by the “insider” art world, with its fine-art degrees and commercial machinations that always struck me as rather hoity-toity. Distinct from folk artists who usually evolved within familiar conventions, outsider artists often worked without precedent in relative isolation. They could be developmentally disabled, visionary, institutionalized, reclusive or simply retirees whose hobbies developed an unexpected intensity and originality. The term has long been the subject of debate, and its meaning has become elastic and inclusive. -

Public Events October 2018

Public Events October 2018 Subscribe to this publication by emailing Shayla Butler at [email protected] Table of Contents Overview Highlighted Events ................................................................................................. 3 Open House Chicago .............................................................................................. 4 Chicago Humanities Festival ................................................................................. 5 Year Long Security Dialogue ................................................................................. 8 Neighborhood and Community Relations Northwestern Events 1603 Orrington Avenue, Suite 1730 Arts Evanston, IL 60201 Music Performances ..................................................................................... 10 www.northwestern.edu/communityrelations Exhibits ......................................................................................................... 13 Theatre .......................................................................................................... 14 Film ............................................................................................................... 15 Dave Davis Arts Discussions ............................................................................................ 17 Executive Director [email protected] Living 847-491-8434 Leisure and Social ......................................................................................... 18 Norris Mini Courses Around Campus ARTica -

Outsider Art Becoming Insider: the Example of Henry Darger

OUTSIDER ART BECOMING INSIDER: THE EXAMPLE OF HENRY DARGER by BADE NUR ÇAYIR Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Sabancı University JUNE 2019 Bade Nur Çayır June 2019 © All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT OUTSIDER ART BECOMING INSIDER: THE EXAMPLE OF HENRY DARGER BADE NUR ÇAYIR CULTURAL STUDIES M.A. THESIS, JUNE 2019 Thesis advisor: Prof. AyĢe Gül Altınay Keywords: outsider art, madness, henry darger, art brut, psychiatry This thesis focuses on the outsider art also known as mad art. The question of how a mad becomes an artist by the art world is examined through the example of Henry Darger, one of the most famous outsider artists. Different biographies of Darger show us the process of construction of outsider artist image. The main aim of this thesis is to question the dynamics of the art world and to discuss how it creates its own limits while creating a new identity. It is discussed how the mad, the subject of psychiatry, is reconstructed in the art world and how this construction affects the art world. In this process, biography is treated as a commodity and considered as the most important element in the establishment of the outsider art. iv ÖZET DIġARIDAN SANATIN ĠÇERĠDEN SANATA DÖNÜġMESĠ: HENRY DARGER ÖRNEĞĠ BADE NUR ÇAYIR YÜKSEK LĠSANS TEZĠ, HAZĠRAN 2019 Tez danıĢmanı: Prof. Dr. AyĢe Gül Altınay Anahtar kelimeler: dıĢarı sanatı, delilik, Henry Darger, psikiyatri Bu tez dıĢarıdan sanat olarak adlandırılan deli sanatına odaklanmaktır. Bir delinin nasıl sanat dünyası tarafından sanatçı haline getirildiği sorusu bilinen en ünlü sanatçılardan biri olan Henry Darger örneği üzerinden incelenmektedir. -

Reading the Pedophile: Deconstruction of Innocence Worship Through the Work of Henry Darger Grace Sparapani Vassar College, [email protected]

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2016 Reading the pedophile: deconstruction of innocence worship through the work of Henry Darger Grace Sparapani Vassar College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Sparapani, Grace, "Reading the pedophile: deconstruction of innocence worship through the work of Henry Darger" (2016). Senior Capstone Projects. Paper 581. This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. READING THE PEDOPHILE Deconstruction of innocence worship through the work of Henry Darger Grace Sparapani Undergraduate Senior Thesis for Diploma Under the direction of Professor Wendy Graham Vassar College | English Department Spring 2016 i Acknowledgments I would like to thank, first and foremost and above anyone else, my advisor Wendy Graham for the immense amount of support she has given me since my freshman year at Vassar. It was Professor Graham who first introduced me to psychoanalytic theory, to structural theory, and to Henry Darger; this thesis would not exist without her academic influence or her emotional guidance. I would like also to thank the other professors who have greatly influenced me over my four years in college and have supported me through my thesis process and my studies beyond. I would like to thank my parents for their support; my roommates Audrey and Samantha; my best friends and secondary roommates Athena, Monica, and Lily; and my friends who have sat with me as I wrote this tome in both times of panic and confidence, including but not limited to George, Kali, Sophie, Grace, Sophia, Joe, and Fiona. -

Compass: Folk Art in Four Directions,” on View at the South Street Seaport Museum, New York, June 20, 2012–February 3, 2013

COMPASS FOLK ART IN FOUR DIRECTIONS An Educators’ Resource AMERICAN FOLK ART MUSEUM NEW YORK Education Department 2012 Published in conjunction with the American Folk Art Museum exhibition “Compass: Folk Art in Four Directions,” on view at the South Street Seaport Museum, New York, June 20, 2012–February 3, 2013. Major support for “Compass” is provided by the Ford Foundation. Additional support is provided by Kendra and Allan Daniel, Lucy and Mike Danziger, Jacqueline Fowler, The Leir Charitable Foundations, The Peter Jay Sharp Foundation, and Donna and Marvin Schwartz. © 2012 BY THE AMERICAN FOLK ART MUSEUM 2 LINCOLN SQUARE NEW YORK, NY 10023 WWW.FOLKARTMUSEUM.ORG EDUCATION DEPARTMENT 212. 265. 1040, EXT. 381 [email protected] CONTENTS CREDITS 4 INTRODUCTION Letter from the Executive Director 5 Letter from the Chief Curator & Director of Exhibitions 6 Letter from the Director of Education 7 How to Use This Guide 8 Teaching from Images and Objects 9 LESSON PLANS An Introduction to Folk Art 1 Noah’s Ark & Funeral for Titanic 11 Exploration 2 Beaver in Arctic Waters & Pair of Scrimshaw Teeth 18 3 Map of the Animal Kingdom 24 4 Possum Trot Figures 28 5 Sea Captain & Child Holding Doll and Shoe 33 Social Networking 6 Untitled (Vivian Girls Watching Approaching Storm in Rural Landscape) 40 7 Isobel and Dixie 45 Shopping 8 Newsboy Show Figure 49 Wind, Water, and Weather 9 Schoolhouse Quilt Top 52 10 Situation of America, 1848 & J.B. Schlegelmilch Blacksmith Shop Sign and Weathervane 58 GLOSSARY 66 BIBLIOGRAPHY AND RESOURCES 68 VISITING THE AMERICAN FOLK ART MUSEUM 71 CREDITS PROJECT DIRECTOR Rachel Rosen Director of Education, American Folk Art Museum PRINCIPAL WRITER Nicole Haroutunian Educator and writer CONTRIBUTING WRITER Jennifer Liriano ARTS Intern 2012 EXHIBITION CURATOR Stacy C. -

American Folk Art Museum

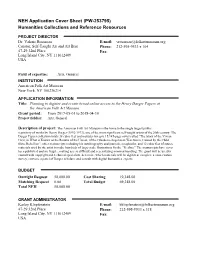

NEH Application Cover Sheet (PW-253795) Humanities Collections and Reference Resources PROJECT DIRECTOR Dr. Valerie Rousseau E-mail: [email protected] Curator, Self-Taught Art and Art Brut Phone: 212-595-9533 x 104 47-29 32nd Place Fax: Long Island City, NY 111012409 USA Field of expertise: Arts, General INSTITUTION American Folk Art Musuem New York, NY 100236214 APPLICATION INFORMATION Title: Planning to digitize and create broad online access to the Henry Darger Papers at the American Folk Art Museum. Grant period: From 2017-05-01 to 2018-04-30 Project field(s): Arts, General Description of project: The American Folk Art Museum is the home to the single largest public repository of works by Henry Darger (1892-1973), one of the most significant self-taught artists of the 20th century. The Darger Papers collection totals 38 cubic feet and includes his epic 15,145-page novel called “The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion”, other manuscripts including his autobiography and journals, scrapbooks, and 12 cubic feet of source materials used by the artist to make hundreds of large-scale illustrations for the “Realms.” The manuscripts have never been published and are fragile, making access difficult and necessitating minimal handling. The grant will be used to consult with copyright and technical specialists, determine which materials will be digitized, complete a conservation survey, convene a panel of Darger scholars, and consult with digital humanities experts. BUDGET Outright Request 50,000.00 Cost Sharing 19,348.00 Matching Request 0.00 Total Budget 69,348.00 Total NEH 50,000.00 GRANT ADMINISTRATOR Karley Klopfenstein E-mail: [email protected] 47-29 32nd Place Phone: 212-595-9533 x 318 Long Island City, NY 111012409 Fax: USA American Folk Art Museum Digitizing the Henry Darger Papers 1. -

How Outsider Art Entered the Inner Sanctum of World-Class Museums: a Q&A with Phillip March Jones by Karen Rosenberg Jan

Expert Eye How Outsider Art Entered the Inner Sanctum of World-Class Museums: A Q&A With Phillip March Jones By Karen Rosenberg Jan. 13, 2016 Phillip March Jones, the director of Andrew Edlin Gallery. At age 16, Phillip March Jones took a detour from a family road trip to visit the Georgia home of the Reverend Howard Finster, the Baptist minister and visionary artist known for his proselytizing paintings and elaborate found-object sculpture garden. “As an aspiring artist in high school, I was really enamored with him,” Jones recalls. “Here was a guy who was unafraid to use any kind of material in any kind of way, who was definitely on his own track.” Thus began a life and career in outsider art, as a gallerist, foundation director, and an artist with an eye for the Southern vernacular. Seven years ago Jones founded Institute 193, a nonprofit contemporary art space and publisher, in Lexington, Kentucky. While running that gallery, he published his own artist book (Points of Departure: Roadside Memorial Polaroids, The Jargon Society, 2012) and became the inaugural director of the now-prominent Souls Grown Deep Foundation, an organization created by the pioneering Southern collector Bill Arnett to preserve the work of self-taught African-American artists—an undertaking soon to be celebrated in an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. An opportunity to open a New York branch of the Paris-based gallery Christian Berst Art Brut brought him to New York a few years later, and in December he joined Andrew Edlin Gallery (one of the city’s top dealers in outsider art) as it settled into a new home on the Bowery right across from the New Museum. -

Public Events November 2018

Public Events November 2018 Subscribe to this publication by emailing Shayla Butler at [email protected] Table of Contents Overview Highlighted Events ................................................................................................. 3 Year Long Security Dialogue .................................................................................. 5 Neighborhood and Community Relations 1603 Orrington Avenue, Suite 1730 Northwestern Events Evanston, IL 60201 Arts www.northwestern.edu/communityrelations Music Performances ....................................................................................... 7 Exhibits ......................................................................................................... 11 Theatre .......................................................................................................... 14 Dave Davis Film ............................................................................................................... 16 Executive Director Arts Discussions ............................................................................................ 17 [email protected] 847-491-8434 Living Leisure and Social ......................................................................................... 18 Norris Mini Courses Around Campus To receive this publication electronically ARTica (art studio) every month, please email Shayla Butler at Norris Outdoors [email protected] Northwestern Music Academy Religious Services .......................................................................................