Pyre: a Poetics of Fire and Childhood in the Art of Henry Darger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glitz and Glam

FINAL-1 Sat, Feb 24, 2018 5:31:17 PM Glitz and glam The biggest celebration in filmmaking tvspotlight returns with the 90th Annual Academy Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment Awards, airing Sunday, March 4, on ABC. Every year, the most glamorous people • For the week of March 3 - 9, 2018 • in Hollywood stroll down the red carpet, hoping to take home that shiny Oscar for best film, director, lead actor or ac- tress and supporting actor or actress. Jimmy Kimmel returns to host again this year, in spite of last year’s Best Picture snafu. OMNI Security Team Jimmy Kimmel hosts the 90th Annual Academy Awards Omni Security SERVING OUR COMMUNITY FOR OVER 30 YEARS Put Your Trust in Our2 Familyx 3.5” to Protect Your Family Big enough to Residential & serve you Fire & Access Commercial Small enough to Systems and Video Security know you Surveillance Remote access 24/7 Alarm & Security Monitoring puts you in control Remote Access & Wireless Technology Fire, Smoke & Carbon Detection of your security Personal Emergency Response Systems system at all times. Medical Alert Systems 978-465-5000 | 1-800-698-1800 | www.securityteam.com MA Lic. 444C Old traditional Italian recipes made with natural ingredients, since 1995. Giuseppe's 2 x 3” fresh pasta • fine food ♦ 257 Low Street | Newburyport, MA 01950 978-465-2225 Mon. - Thur. 10am - 8pm | Fri. - Sat. 10am - 9pm Full Bar Open for Lunch & Dinner FINAL-1 Sat, Feb 24, 2018 5:31:19 PM 2 • Newburyport Daily News • March 3 - 9, 2018 the strict teachers at her Cath- olic school, her relationship with her mother (Metcalf) is Videoreleases strained, and her relationship Cream of the crop with her boyfriend, whom she Thor: Ragnarok met in her school’s theater Oscars roll out the red carpet for star quality After his father, Odin (Hop- program, ends when she walks kins), dies, Thor’s (Hems- in on him kissing another guy. -

Verspielter Nihilismus

# 2019/44 dschungel https://jungle.world/artikel/2019/44/verspielter-nihilismus Die Vivian Girls sind wütender denn je Verspielter Nihilismus Von Suse Fischer Nach zwischenzeitlicher Bandauflösung gibt es die Vivian Girls wieder – und sie sind wütender denn je. Fünf Jahre ist es her, dass sie sich offiziell auflösten, doch nun brachte die New Yorker Band Vivian Girls frisch wiedervereint mit »Memory« im September ihr viertes Studioalbum heraus. Die zwei ständigen Mitglieder Cassie Ramone und Katy Goodman gehörten in den späten nuller Jahren zunächst zusammen mit Frankie Rose an den Drums – seit dem zweiten Album »Everything Goes Wrong« ist Ali Koehler die Schlagzeugerin der Band – zum Kern der damals florierenden Noise-Pop-Garage-Punk- Szene in Brooklyn um Bands wie die Dum Dum Girls und DIIV. Sechziger-Jahre-Pop-Soundmuster mischen sich auf »Memory« mit äußerst wütenden Riffs. Im Gegensatz zu dem verstrahlten Feelgood-Sound von Bands, die diesem Genre zugeordnet werden können, wie beispielsweise Best Coast (deren Lieder hauptsächlich davon handeln, dass es die Sonne, das Meer und süße Boys gibt und ja, okay, ein bisschen seltsam traurig ist man vielleicht auch, aber es gibt die Sonne, es gibt das Meer, – repeat!), wohnte bereits den früheren Alben der Vivian Girls mit ihren harmonischen, an die Band Warpaint erinnernden choralen Backroundgesängen doch eine gewisse Härte inne, die sich in einem verspielten Nihilismus immer wieder Bahn brach. Was sich damals lediglich erahnen ließ, nimmt nun auf »Memory« deutlich Form an. Verträumt perlende Sechziger-Jahre-Pop-Soundmuster wie von den Shangri-Las (unüberhörbar die Vorbilder der Vivian Girls) mischen sich mit äußerst wütenden Riffs. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

COSMETOLOGY CURRICULUM | Styling

COSMETOLOGY CURRICULUM | Styling Book ONE | Student Guide COSMETOLOGY CURRICULUM | Styling TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction to Styling Hair..................................................................3 2. Finger Waving Technique........................................................................11 3. Curl Bases and Stems................................................................................18 4. Pin Curls (Flat and Volume)....................................................................22 5. Roller Setting and Curl Variations........................................................34 6. Back-Combing and Back-Brushing.......................................................40 7. Half-Round Brush Air Forming Technique........................................45 8. Round Brush Styling Technique............................................................51 9. Finger Drying and Palm Drying............................................................57 10. Thermal Techniques for Curling...........................................................62 11. Thermal Techniques for Creating Waves.........................................73 12. Thermal Techniques for Smoothing and Straightening.............81 13. French Twist................................................................................................91 14. Draped Style...............................................................................................97 15. Chignon........................................................................................................101 -

Concert Series

•~.t: 16,000 People Read th» opening with a salm $Afb e Published Every Tuesday - "Justice to ails Bf the 112th Fit-id Ar 1 Now Jersey Nation^ _L and Friday Noon. malice toward none. * rnof Moore was in. : ana there was SIR-;. and SUMMIT RECORD abined chorus as well FORTY'-THIRD YEAR. NO. 78 SUMMIT, N,JW FRIDAY AFTERNOON, JUNE 3, 1932 $3.50 PER YEAR lows In Summit - •."••'••• : \' • • • Three in Holehouse, chair- TWO COPS,FIND TWO COPS! smorlal committee of Concert Series Coddington Talks Lacking Money to Pay Fines Judge Williams Many Summit Girls "AreiitWeiirat brothers, is ami "Somebody's breaking into Day tarations for tin- Apparently Ends the Ash wood Pharmacy," the is to be held the excited voice of - a woman to the Old Guard Will Revoke Licenses-Traffic Court Cases Kent Place Seniors Hogs, it appears, were apparent- The Playhouse June, in the even, , shrilled over the telephone in ly offered a day In which to get all u the biting they- cared to do out of >yterlan Church at I Subscriptkig Concert s police headquarters Wednesday Justice Hobert B. Williams an- chanic. was arraigned for n 42-mlle Describes the Work of nounced last night In Traffic Court nu .hour, speeding charge preferred Twenty Will Graduate their systems. What is more, they Clever Super«Cast Pre- ie urges all t),S(i jf- .' night. e! Fails ^Receive Re- The sergeant In charge.,, hop- Growing and Creating that hereafter defendants lacking by Officer Van Tionk, lie received With Record Class Mon- apparently chose Wednesday, June ing to nip the probable bur- the amount of their fine will have a-suspended sentence when ho ox- 1st. -

Darger, Henry (1892-1973) by Jim Elledge

Darger, Henry (1892-1973) by Jim Elledge Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2013 glbtq,Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Now considered one of the most original and important artists of the last half of the twentieth century, Henry Darger died completely unknown in his native Chicago. When he moved out of his one-room apartment on November 24, 1972 into an old folks home a few blocks away, his next door neighbor, who had been hired to clear out Darger's room, discovered over 300 canvases Darger had painted and the huge manuscripts of two novels and an autobiography that he had written. The canvases, which depict naked little girls with penises (who, in many of the paintings, are being eviscerated, strangled, and crucified by adults), became synonymous with the man, causing critics who were unaware of their relevance to the gay subculture of the time to call Darger a pedophile, child killer, and sadist. Darger's Life Darger was born into utter poverty on April 12, 1892. His mother died in childbirth when he was four. Within a few years, his father, a failed, alcoholic tailor, had all but abandoned his parental responsibilities to the boy. Growing up in one of the darkest and most desperate vice districts in Chicago, now Henry Darger. Photo by the much-gentrified Near West Side, Darger became involved in male-male sexual David Berglund, c. 1970. activities early in life, admitting to the most significant one in his autobiography decades later. In it, he reported that, by the time he was eight years old, he had developed a relationship with an adult guard whom he visited late at night at the lumberyard where the man worked. -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

Lgbts Confront Persecution

Volume 85 - Issue 10 November 16, 2012 LGBTs confront persecution Airband to Campus group offers support to LGBT students take the place BY TYLER LEHMANN of NBDC FEATURES CO-EDITOR BY GILLIAN ANDERSON Recalling dirty looks on campus and A once-popular Northwestern event, harassment in dorms, Northwestern Airband, will be introduced to a new College’s lesbian, gay, bisexual and generation of students. transgender students said they are Airband is a competition in which “persecuted” at the school. In response, groups create a lip-syncing performance NW’s unofficial student-run LGBT to a song or mix of songs. advocacy group has expanded its efforts “It is lip syncing but not the band to raise awareness of perceived LGBT type of lip syncing,” said Aaron discrimination on campus. Beadner, director of student programs. “Everyone should have a place where Most students were still in high they feel safe and free to be who they school when Airband last took place are and not feel judged or persecuted, and on campus four years ago. Some we want to be that for anyone who needs former students who remember it us,” said senior Keely Wright, executive are now working for NW, and a few administrator of LEAP, an organization current students have heard about it for LGBT-affirming students that is from recent graduates. unaffiliated with NW. “I remember Airband as a student,” Taking its name from the acronym said Drew Schmidt who graduated “Love, Education, Acceptance, Pride,” from NW in 2005 and is now the the group clashes with NW’s official audiovisual technician at NW. -

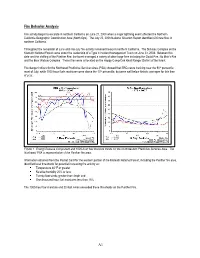

A1 Fire Behavior Analysis

Fire Behavior Analysis Fire activity began to escalate in northern California on June 21, 2008 when a major lightning event affected the Northern California Geographic Coordination Area (North Ops). The July 22, 2008 National Situation Report identified 602 new fires in northern California. Throughout the remainder of June and into July fire activity remained heavy in northern California. The Siskiyou Complex on the Klamath National Forest came under the leadership of a Type II Incident Management Team on June 23, 2008. Between this date and the staffing of the Panther Fire, the forest managed a variety of other large fires including the Gould Fire, No Man‘s Fire and the Bear Wallow Complex. These fires were all located on the Happy Camp/Oak Knoll Ranger District of the forest. Fire danger indices for the Northwest Predictive Services Area (PSA) showed that ERCs were tracking near the 90th percentile most of July, while 1000-hour fuels moistures were above the 10th percentile, but were well below historic averages for this time of year. Figure 1. Energy Release Component and 1000-hour fuel moisture trends for the Northwestern Predictive Services Area. The Northwest PSA is representative of the Panther fire area. Information obtained from the Pocket Card for the western portion of the Klamath National Forest, including the Panther fire area, identified local thresholds for potential increasing fire activity as: Temperature 85°F or greater Relative humidity 20% or less Twenty-foot winds greater than 4mph and One-thousand hour fuel moistures less than 15% The 1000-hour fuel moisture and 20-foot winds exceeded these thresholds on the Panther Fire. -

The Henry Darger Study Center at the American Folk Art Museum a Collections Policy Recommendation Report

The Henry Darger Study Center at the American Folk Art Museum A Collections Policy Recommendation Report by Shannon Robinson Spring 2010 I. Overview page 3 II. Mission and Goals page 5 III. Service Community and Programs page 7 IV. The Collection and Future Acquisition page 8 V. Library Selection page 11 VI. Responsibilities page 12 VII. Complaints and Censorship page 13 VIII. Evaluation page 13 IX. Bibliography page 15 X. Additional Materials References page 16 I. Overview The American Folk Art Museum in New York City is largely focused on the collection and preservation of the artwork of self-taught artists in the United States and abroad. The Museum began in 1961 as the Museum of Early American Folk Arts; at that time, the idea of appreciating folk art alongside contemporary art was a consequence of modernism (The American Folk Art Museum, 2010c). The collection’s pieces date to as early as the eighteenth century and in it’s earlier days was largely comprised of sculpture. The Museum approached collecting and exhibiting much like a contemporary art gallery. This was in support of its mission promoting the “aesthetic appreciation” and “creative expressions” of folk artists as parallel in content and quality to more mainstream, trained artists. (The American Folk Art Museum, 2010b). Within ten years of opening, however, and though the collection continued to grow, a financial strain hindered a bright future for the Museum. In 1977, the Museum’s Board of Trustees appointed Robert Bishop director (The American Folk Art Museum, 2010c). While Bishop was largely focused on financial and facility issues, he encouraged gift acquisitions, and increasing the collection in general, by promising many artworks from his personal collection. -

(FCC) Complaints About Saturday Night Live (SNL), 2019-2021 and Dave Chappelle, 11/1/2020-12/10/2020

Description of document: Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Complaints about Saturday Night Live (SNL), 2019-2021 and Dave Chappelle, 11/1/2020-12/10/2020 Requested date: 2021 Release date: 21-December-2021 Posted date: 12-July-2021 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Request Federal Communications Commission Office of Inspector General 45 L Street NE Washington, D.C. 20554 FOIAonline The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. Federal Communications Commission Consumer & Governmental Affairs Bureau Washington, D.C. 20554 December 21, 2021 VIA ELECTRONIC MAIL FOIA Nos. -

Introduction to Fire Behavior Modeling (2012)

Introduction to Fire Behavior Modeling Introduction to Wildfire Behavior Modeling Introduction Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................ 5 Chapter 1: Background........................................................................................ 7 What is wildfire? ..................................................................................................................... 7 Wildfire morphology ............................................................................................................. 10 By shape........................................................................................................ 10 By relative spread direction ........................................................................... 12 Wildfire behavior characteristics ........................................................................................... 14 Flame front rate of spread (ROS) ................................................................... 15 Heat per unit area (HPA) ................................................................................ 17 Fireline intensity (FLI) .................................................................................... 19 Flame size ..................................................................................................... 23 Major influences on fire behavior simulations ....................................................................... 24 Fuelbed structure .........................................................................................