Do Japanese Candlesticks Help Solving the Trader's Dilemma?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stock Market Explained

Stock Market Explained A Beginner's Guide to Investing and Trading in the Modern Stock Market © Ardi Aaziznia www.PeakCapitalTrading.com Copyrighted Material © Peak Capital Trading CHAPTER 1 Copyrighted Material © Peak Capital Trading Figure 1.1: “covid-19” and “stock market” keyword Google search trends between April 2019 and April 2020. As you can see, there is a clear correlation. As the stock market drop hit the news cycles, people started searching more and more about the stock market in Google! Copyrighted Material © Peak Capital Trading COVID-19 Bear Market 2019 Bull Market 2020 recession due to pandemic v Figure 1.2: Comparison between the bull market of 2019 and the bear market of 2020, as shown by the change in share value of 500 of the largest American companies. These companies are tracked by the S&P 500 and are traded in an exchange-traded fund known as the SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust (ticker: SPY). For your information, S&P refers to Standard & Poor’s, one of the indices which used to track this information. Copyrighted Material © Peak Capital Trading Figure 1.3: How this book is organized. Chapters 1-4 and 7-11 are written by me. Chapters 5 and 6 on day trading are written by Andrew Aziz. Copyrighted Material © Peak Capital Trading CHAPTER 2 Copyrighted Material © Peak Capital Trading Figure 2.1: The return on investing $100 in an exchange-traded fund known as the SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust (ticker: SPY) (which tracks the share value of 500 of the largest American companies (as rated by the S&P 500)) vs. -

The Best Candlestick Patterns

Candlestick Patterns to Profit in FX-Markets Seite 1 RISK DISCLAIMER This document has been prepared by Bernstein Bank GmbH, exclusively for the purposes of an informational presentation by Bernstein Bank GmbH. The presentation must not be modified or disclosed to third parties without the explicit permission of Bernstein Bank GmbH. Any persons who may come into possession of this information and these documents must inform themselves of the relevant legal provisions applicable to the receipt and disclosure of such information, and must comply with such provisions. This presentation may not be distributed in or into any jurisdiction where such distribution would be restricted by law. This presentation is provided for general information purposes only. It does not constitute an offer to enter into a contract on the provision of advisory services or an offer to buy or sell financial instruments. As far as this presentation contains information not provided by Bernstein Bank GmbH nor established on its behalf, this information has merely been compiled from reliable sources without specific verification. Therefore, Bernstein Bank GmbH does not give any warranty, and makes no representation as to the completeness or correctness of any information or opinion contained herein. Bernstein Bank GmbH accepts no responsibility or liability whatsoever for any expense, loss or damages arising out of, or in any way connected with, the use of all or any part of this presentation. This presentation may contain forward- looking statements of future expectations and other forward-looking statements or trend information that are based on current plans, views and/or assumptions and subject to known and unknown risks and uncertainties, most of them being difficult to predict and generally beyond Bernstein Bank GmbH´s control. -

Trading System Development

Trading System Development An Interactive Qualifying Project Submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science By Brian O’Day Dylan Stimson Branden Diniz Submitted to: Prof. Michael Radzicki (advisor) Prof. Hossein Hakim (co-advisor) May 9, 2015 Abstract The purpose of this project was to construct a system of trading systems that would demonstrate a successful long term return on investment across different market conditions. The team was given $300,000 to distribute amongst three scientifically developed systems on the TradeStation platform provided by our advisors. The strategies were designed to incorporate both technical and fundamental data as well as trade diverse markets. The resulting cultivation of systems involved the use of two automated trading strategies and one manual trading strategy that showed substantial profits in the long term. 1 Acknowledgments We would like to thank Professor Radzicki and Professor Hakim for their guidance and support throughout the course of the project. We would also like to thank TradeStation for providing us with a platform for trading that made this project possible. 2 Authorship Page Introduction - Brian Problem Statement - Brian Overview of Systems - All Foundations of Trading and Investing Trading vs Investing - Branden Types of Exchanges - Branden, Dylan Investment Funds - Dylan Types of Orders - Dylan Market Conditions - Dylan Trading different Time Frames - Brian, Branden Costs of Trading/Investing -

Candlestick Patterns

INTRODUCTION TO CANDLESTICK PATTERNS Learning to Read Basic Candlestick Patterns www.thinkmarkets.com CANDLESTICKS TECHNICAL ANALYSIS Contents Risk Warning ..................................................................................................................................... 2 What are Candlesticks? ...................................................................................................................... 3 Why do Candlesticks Work? ............................................................................................................. 5 What are Candlesticks? ...................................................................................................................... 6 Doji .................................................................................................................................................... 6 Hammer.............................................................................................................................................. 7 Hanging Man ..................................................................................................................................... 8 Shooting Star ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Checkmate.......................................................................................................................................... 9 Evening Star .................................................................................................................................... -

© 2012, Bigtrends

1 © 2012, BigTrends Congratulations! You are now enhancing your quest to become a successful trader. The tools and tips you will find in this technical analysis primer will be useful to the novice and the pro alike. While there is a wealth of information about trading available, BigTrends.com has put together this concise, yet powerful, compilation of the most meaningful analytical tools. You’ll learn to create and interpret the same data that we use every day to make trading recommendations! This course is designed to be read in sequence, as each section builds upon knowledge you gained in the previous section. It’s also compact, with plenty of real life examples rather than a lot of theory. While some of these tools will be more useful than others, your goal is to find the ones that work best for you. Foreword Technical analysis. Those words have come to have much more meaning during the bear market of the early 2000’s. As investors have come to realize that strong fundamental data does not always equate to a strong stock performance, the role of alternative methods of investment selection has grown. Technical analysis is one of those methods. Once only a curiosity to most, technical analysis is now becoming the preferred method for many. But technical analysis tools are like fireworks – dangerous if used improperly. That’s why this book is such a valuable tool to those who read it and properly grasp the concepts. The following pages are an introduction to many of our favorite analytical tools, and we hope that you will learn the ‘why’ as well as the ‘what’ behind each of the indicators. -

Timeframeset

QuantShare Programming Language Table of contents 1. QuantShare Language 1.1 Application Info 1.1.1 NbGroups 1.1.2 NbIndexes 1.1.3 NbIndustries 1.1.4 NbInGroup 1.1.5 NbInIndex 1.1.6 NbInIndustry 1.1.7 NbInMarket 1.1.8 NbInSector 1.1.9 NbMarkets 1.1.10 NbSectors 1.2 Candlestick Pattern 1.2.1 Cdl2crows (0) 1.2.2 Cdl2crows (1) 1.2.3 Cdl3blackcrows (0) 1.2.4 Cdl3blackcrows (1) 1.2.5 Cdl3inside (0) 1.2.6 Cdl3inside (1) 1.2.7 Cdl3linestrike (0) 1.2.8 Cdl3linestrike (1) 1.2.9 Cdl3outside (0) 1.2.10 Cdl3outside (1) 1.2.11 Cdl3staRsinsouth (0) 1.2.12 Cdl3staRsinsouth (1) 1.2.13 Cdl3whitesoldiers (0) 1.2.14 Cdl3whitesoldiers (1) 1.2.15 CdlAbandonedbaby (0) 1.2.16 CdlAbandonedbaby (1) 1.2.17 CdlAdvanceblock (0) 1.2.18 CdlAdvanceblock (1) 1.2.19 CdlBelthold (0) 1.2.20 CdlBelthold (1) 1.2.21 CdlBreakaway (0) 1.2.22 CdlBreakaway (1) 1.2.23 CdlClosingmarubozu (0) 1.2.24 CdlClosingmarubozu (1) 1.2.25 CdlConcealbabyswall (0) 1.2.26 CdlConcealbabyswall (1) 1.2.27 CdlCounterattack (0) 1.2.28 CdlCounterattack (1) 1.2.29 CdlDarkcloudcover (0) 1.2.30 CdlDarkcloudcover (1) 1.2.31 CdlDoji (0) 1.2.32 CdlDoji (1) 1.2.33 CdlDojistar (0) 1.2.34 CdlDojistar (1) 1.2.35 CdlDragonflydoji (0) 1.2.36 CdlDragonflydoji (1) 1.2.37 CdlEngulfing (0) 1.2.38 CdlEngulfing (1) 1.2.39 CdlEveningdojistar (0) 1.2.40 CdlEveningdojistar (1) 1.2.41 CdlEveningstar (0) 1.2.42 CdlEveningstar (1) 1.2.43 CdlGapsidesidewhite (0) 1.2.44 CdlGapsidesidewhite (1) 1.2.45 CdlGravestonedoji (0) 1.2.46 CdlGravestonedoji (1) 1.2.47 CdlHammer (0) 1.2.48 CdlHammer (1) 1.2.49 CdlHangingman (0) 1.2.50 -

Candlestick and Pivot Point Trading Triggers

ffirs.qxd 9/25/06 10:00 AM Page iii Candlestick and Pivot Point Trading Triggers Setups for Stock, Forex, and Futures Markets JOHN L. PERSON John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirs.qxd 9/25/06 10:00 AM Page iv Copyright © 2007 by John L. Person. All rights reserved. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. Published simultaneously in Canada. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as per- mitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646- 8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or com- pleteness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. -

Bullish Pattern Created by Connecting Two Or More Lows, with Each Successive Low Higher Than the Previous Low

1 Account Value: The account value is how much one’s account is worth. ADP Non Farm Employment Change: This U.S. report is a measure of non-farm private employment. It was developed in order to help meet the need for timely and accurate estimates of short-term movements in the labor market. Analyst: When analyzing the market, analysts can generally be divided into two camps – fundamentals and technicals. Fundamental analysts are those who mainly look at the fundamental aspects of an economy in forming their opinions. They stay on top of the markets by reading and analyzing what the current economic data say about current market conditions, what is fundamentally driving the market, and where it’s headed. Technical analysts are those who primarily rely on chart indicators and patterns to help predict where price will move next. Some tools that technical analysts use are Fibonacci retracement, candlesticks and momentum indicators. Ascending Trend Channel: An ascending trend channel is a basic chart pattern used in technical analysis. Ascending trend channels are a useful tool due to their ability to predict overall changes in trend. As long as prices remain within the ascending trend channel, the upward trend in price can be expected to continue. As soon as prices exceed either trendline forming the channel, however, a strong signal either to buy or to sell is generated. A break through the upper trendline generates a strong buy signal, while a break through the lower trendline generates a strong sell signal. Ascending Trend Line: A bullish pattern created by connecting two or more lows, with each successive low higher than the previous low. -

5-Step-Trading Fx ® Workbook

1 L E X¶S FAV O URI T E T E C H NI C A L T R A DIN G ST R AT E G I ES F O R F X - W O R K B O O K This workbook is intended to accompany the /H[¶VF avourite Technical Trading Strategies for F X - Applicable to Commodities and Equity Indexes as well online module. WORKBOOK QU ESTION: Why do you think technical indicators make trading less emotional and more objective? 2 Table of contents Types of traders ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Technical indicators: Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 7 Technical indicators: Leading Indicators ................................................................................................................ 9 a) Support & Resistance, Fibonacci retracement levels and Floor Pivot points ............................................. 9 b) Relative Strength Index (RSI) .................................................................................................................. 13 c) Stochastic Oscillator ................................................................................................................................. 14 Technical indicators: Lagging Indicators .............................................................................................................. 16 a) Moving Averages ..................................................................................................................................... -

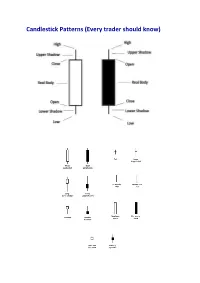

Candlestick Patterns (Every Trader Should Know)

Candlestick Patterns (Every trader should know) A doji represents an equilibrium between supply and demand, a tug of war that neither the bulls nor bears are winning. In the case of an uptrend, the bulls have by definition won previous battles because prices have moved higher. Now, the outcome of the latest skirmish is in doubt. After a long downtrend, the opposite is true. The bears have been victorious in previous battles, forcing prices down. Now the bulls have found courage to buy, and the tide may be ready to turn. For example = INET Doji Star A “long-legged” doji is a far more dramatic candle. It says that prices moved far higher on the day, but then profit taking kicked in. Typically, a very large upper shadow is left. A close below the midpoint of the candle shows a lot of weakness. Here’s an example of a long-legged doji. For example = K Long-legged Doji A “gravestone doji” as the name implies, is probably the most ominous candle of all, on that day, price rallied, but could not stand the altitude they achieved. By the end of the day. They came back and closed at the same level. Here ’s an example of a gravestone doji: A “Dragonfly” doji depicts a day on which prices opened high, sold off, and then returned to the opening price. Dragonflies are fairly infrequent. When they do occur, however, they often resolve bullishly (provided the stock is not already overbought as show by Bollinger bands and indicators such as stochastic). For example = DSGT The hangman candle , so named because it looks like a person who has been executed with legs swinging beneath, always occurs after an extended uptrend The hangman occurs because traders, seeing a sell-off in the shares, rush in to grab the stock a bargain price. -

Jul/Aug 2009

CHART PATTERNS SECTORS MARKET UPDATE Yahoo! Developing Energy NASDAQ 100 A Bullish Triangle Consolidating Outperforms JULY/AUGUST 2009 US$7.95 .com THE MAGAZINE FOR INSTITUTIONAL AND PROFESSIONAL TRADERS TM CANTr YOU HANDLEaders THE DRAWDOWNS? Trading systems 101 10 EIGHT STRAIGHT WEEKS Two months of steady gains? 18 WILL DIAMONDS BREAK THE BANKS? Stopping the bulls in their tracks 20 short-TERM VIEW OF GOLD Fibonacci levels may affect price 25 COILS AND LEDGES The less volatile they are… 30 YAHOO GAPS UP Will the trend reversal breakout pull Yahoo higher? 35 WHAT BIG RALLY? XLF DAILY VS. XLF HOURLY Step back and look 39 APPLE ABOVE BAND Will the rally continue? 41 MAILING LABEL Change service requested service Change 98116-4499 WA ttle, Sea XLF, DAILY. Prices may form a higher low and XLF, HOURLY. Prices gap lower from the bearish diamond pattern as 4757 California Ave. SW Ave. California 4757 begin to channel high. negative divergence begins unraveling on the MACD. Traders.com page 2 • Traders • With The Higher Volatility And 300-500 Point Dow Moves In A Day, 3 Interviews At Why More and More Investors Trust My Day Trading Profi ts Are Approximately 4 Times Higher Than In 2007 Interview Mr. Jim Kane – A Trader Using AbleSys Software www.ablesys.com .com AbleTrend to Make Their Trading Decisions Mr. Jim Kane, How long have you been trading? What is the most important factor in trading? How does I have been trading, on and off, for 20 years. Several times AbleTrend help? I got so frustrated that I switched to mutual funds, but that Risk management. -

Index.Pdf (69.91KB)

26_178089 bindex.qxp 2/27/08 9:38 PM Page 329 Index • Symbols & • B • Numerics • bar charts candlestick chart, compared to, 19, 20, %K (fast) stochastic oscillators, 263 317–319 %D (slow) stochastic oscillators, 263 defined, 10, 27–28 5-day moving average, 253–254, 256, 257, single line, 28 258–260 on Web sites, 53 10-day moving average, 259–260 BEA Systems, 220 20-day moving average, 255, 256, 258–260 bear market, defined, 22 24-hour electronic trading Bear Stearns Companies, Inc., 147 high and low prices, futures, 36–37 bearish state volume, relationship to, 25 candlestick charting and patterns, 20–22, 30-minute chart, 74–75 279–290 200-day moving average, 253 closing price as body of candlestick, 38 defined, 96 double-stick patterns • A • dark cloud cover, 172–174 abandoned baby doji star, 167–168 bearish, 229–231 engulfing pattern, 156–158 bullish, 199–201 harami, 159–161 affordability and trading choices, 15 harami cross, 161–164 after-hours trading inverted hammer, 164–167 high and low prices, futures, 36–37 meeting line, 168–172 volume, relationship to, 25 neck lines, 180–183 Alcoa, 170, 171 piercing line, 172–174 Altera Corp., 304 separating lines, 178–180 Amazon.com, 269 thrusting lines, 175–177 American Express, 310–311 sell indicators, 279–290 American Stock Exchange (AMEX), 33, 68 single-stick pattern Amgen, Inc., 151–152 belt hold, 113 Analog Devices Inc., 206–207 doji, 90–94 Apple Computer, 93–94, 168, 169, 276, gravestone doji, 90–94 292–293 long black candle, 84–90 Applebee’s International, 221–222 long marubozus, 86–88