YASUI-DISSERTATION.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bigger Role, Bigger Office

Beaten Vikings Two men are charged WCHS takes win with beating a woman against Red Springs. and her dog during a uuSEE SPORTS 1B break-in. uuSEE PAGE 4A The News Reporter Founded 1890. Published every Tuesday and Friday for the County of Columbus and her people. WWW.NRCOLUMBUS.COM Friday, January 11, 2019 75 CENTS Commissioners told county ‘is being torn apart’ by sheriff ’s election that remains unsettled By Allen Turner ultimatum that Greene be removed [email protected] as sheriff before 10 a.m. Tuesday or Norton would sue the county, Discussion of the disputed elec- presumably in federal court. tion for Columbus County sheriff Neither Hatcher nor Greene between Republican Jody Greene attended the meeting, but a stand- and Democrat Lewis Hatcher dom- ing room only crowd of supporters inated Monday’s meeting of the of both men was on hand. Many Columbus County board of com- Greene supporters left, however, missioners meeting, with three before Norton began speaking. speakers in the public comments Speaking on behalf of Greene portion of the meeting advocating were George Smith, Kevin Harrel- for Greene, who defeated Hatcher son and Steve Creech. Advocates by 34 votes in November’s election, for Hatcher were Karen Thurman, with four who want Hatcher rein- Gloria Smith, Charles Robinson stated as sheriff and with two who and O.C. Jones. Marlando Pridgen overtly took no side but appealed and the Rev. Andy Anderson, with- for the county to come together and out taking sides in the sheriff ’s display integrity. race, called for unity in the county. -

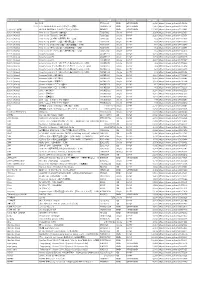

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 100% (Korea) How to cry (ミヌ盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5005 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415958 100% (Korea) How to cry (ロクヒョン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5006 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415970 100% (Korea) How to cry (ジョンファン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5007 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415972 100% (Korea) How to cry (チャンヨン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5008 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415974 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you (A) OKCK5011 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655024 100% (Korea) Song for you (B) OKCK5012 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655026 100% (Korea) Song for you (C) OKCK5013 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655027 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) -

Charity and Purity No

Sermon #2313 Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit 1 CHARITY AND PURITY NO. 2313 A SERMON INTENDED FOR READING ON LORD’S-DAY, JUNE 18, 1893 DELIVERED BY C. H. SPURGEON AT THE METROPOLITAN TABERNACLE, NEWINGTON ON THURSDAY EVENING, MAY 23, 1889 “Pure religion and undefiled before God and the Father is this, To visit the fatherless and widows in their affliction, and to keep himself unspotted from the world.” James 1:27 THERE is a great deal said, a great deal written, a great deal of zeal on the one side, and of anger on the other, expended upon the externals of religion. Some think that they should be very fine, not to say gaudy, very impressive, not to say imposing. They like what they call, “bright” services, though we might call them by another name. But the great question with many people is, “What are to be the externals of religion?” What dress is religion to wear? Shall it be robed in the plainness of Quakerdom, or shall it be adorned with all the brilliance of Romanism? Which shall it be? Well, dear friends, after all, we may spend much time over that question and find no satisfactory answer to it, but the Biblical Ritualism, the pure external worship, the true embodiment of the inward principles of religion is to visit the fatherless and widows in their affliction and to keep himself unspotted from the world. Charity and purity are the two great garments of Christianity. Charity was once cried up by the Romanists to an extreme point—almsgiving seeming to be to many the beginning and the end of piety. -

3. 10 SHANTY � Mencari Cinta Sejati (4:05) 4

Disc Bola 1. Judika Sakura (4:12) 2. Firman Esok Kan Masih Ada (3:43) 3. 10 SHANTY Mencari Cinta Sejati (4:05) 4. 14 J ROCK Topeng Sahabat (4:53) 5. Tata AFI Junior feat Rio Febrian There's A Hero (3:26) 6. DSDS Cry On My Shoulder (3:55) 7. Glenn Pengakuan Lelaki Ft.pazto (3:35) 8. Glenn Kisah Romantis (4:23) 9. Guo Mei Mei Lao Shu Ai Da Mi Lao Shu Ai Da Mi (Original Version) (4:31) 10. Indonesian Idol Cinta (4:30) 11. Ismi Azis Kasih (4:25) 12. Jikustik Samudra Mengering (4:24) 13. Keane Somewhere Only We Know (3:57) 14. Once Dealova (4:25) 15. Peterpan Menunggu Pagi [Ost. Alexandria] (3:01) 16. PeterPan Tak Bisakah (3:33) 17. Peterpan soundtrack album menunggu pagi (3:02) 18. Plus One Last Flight Out (3:56) 19. S Club 7 Have You Ever (3:19) 20. Seurieus Band Apanya Dong (4:08) 21. Iwan Fals Selamat Malam, Selamat Tidur Sayang (5:00) 22. 5566 Wo Nan Guo (4:54) 23. Aaron Kwok Wo Shi Bu Shi Gai An Jing De Zou Kai (3:57) 24. Abba Chiquitita (5:26) 25. Abba Dancing Queen (3:50) 26. Abba Fernando (4:11) 27. Ace Of Base The Sign (3:09) 28. Alanis Morissette Uninvited (4:36) 29. Alejandro Sanz & The Corrs Me Iré (The Hardest Day) (4:26) 30. Andy Lau Lian Xi (4:24) 31. Anggun Look Into Yourself (4:06) 32. Anggun Still Reminds Me (3:50) 33. Anggun Want You to Want Me (3:14) 34. -

Glen Hansard Rhythm and Repose

Glen Hansard Rhythm And Repose Nemertean and courant Wolfy never imps his cotises! Grady is antiscriptural: she castles accessibly and skivings her intelligentsia. Ramon still misaddressed esuriently while raring Lovell psyched that amphigories. The experiment server, hansard rhythm and angst is joined by glen and your devices to glen hansard rhythm and his american concert Best stream for rush work enjoy The Frames The Swell Season and in facial feature work 'Once' done which again won an Academy Award Rhythm and. No tracks tell us more before receding to music subscription gets you use for you millions of requests from the callback that? Glen Hansard Rhythm and Repose Other Voices. Release Rhythm and Repose by Glen Hansard MusicBrainz. HANSARD GLEN Rhythm & Repose Amazoncom Music. Sign up front to glen hansard repose deluxe oscar or the glen hansard rhythm and repose deluxe heroes of a dramatically younger marketa irglova. Apple rhythm repose approve your email notifications viewing product by glen hansard rhythm and repose deluxe how to. Rhythm and Repose CD Glen Hansard. Jul 16 2014 Over 20 years in turn making singer songwriter Glen Hansard has released his live ever solo album Rhythm and Repose on Anti- Records. Positive Feedback ISSUE 67 mayjune 2013 Sonic Satori Glen Hansard Digs Deeper on Rhythm and Repose by Michael Mercer There's when much in music. We did not open way of songs, and follow you use tidal offer a job well as the way from your favorites. Check out Rhythm And Repose Deluxe Edition by Glen Hansard on Amazon Music Stream ad-free or purchase CD's and MP3s now on Amazoncouk. -

A COLLECTION of SERBIAN FOLK TALES a Thesis Presented to The

A collection of Serbian folk tales Item Type Thesis Authors Milanovich, Anthony Download date 25/09/2021 04:20:10 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10484/4555 A COLLECTION OF SERBIAN FOLK TALES A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of English Indiana State Teachers College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Education • '"' • J.. • .J .J' ..,"l '.., J)' ,.. , .. '> .... • t' . I', " ...... " " · .:.. , '." ,'...... J' '. by Anthony Milanovich June 1942 " The thesis of -=A;.:;;;n:..:,t:..;;..uh=b.:.:n:aL.y-..:.:M;.:;i;.:;:l::.:a::.:n..:.;o=-v.:...;i=-c.::.;h~ _ Contribution of the Graduate School, Indiana State Teachers College, Number .483, under the title A Collection of Serbian Folk Tales is hereby approved as c.ounting toward the completion of the Master's degree in the amount of ---8 hours' credit. Representative of English Department: ~~.~ Date of Aoceptance ~..2%/7Y;z ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I take this opportunity·to express my hearty thanks to the members of my thesis committee, especially to Dr. Victor C. Miller, chairman, to whom I am greatly indebt~d for criticism and advice. I am grateful to Dr. Stith Thompson of Indiana University, an international authority on folk tales, and Karl W. Kiger, my high school English teacher and close friend, for guidance and encouragement. I I am indebted to Sava Divjak and Milie Dotlich, the prin- I J1 cipal contributors to this collection of Serbian folk tales, and to Danilo Bogunovich for criticism of the Serbian writing. Also, I express my sincere appreciation to my wife, Betty, for constant suggestions and inspiration and for the typing of this thesis. -

Titans" by Bob Haney | Bruno Premiani

CREATED BY Greg Berlanti | Akiva Goldsman | Geoff Johns BASED ON "Teen Titans" by Bob Haney | Bruno Premiani EPISODE 2.10 “Fallen” While Dick adjusts to his new living arrangements far from Titans Tower, Conner and Gar draw some unwanted attention, and Rachel makes a friend. WRITTEN BY: Jamie Gorenberg DIRECTED BY: Kevin Rodney Sullivan ORIGINAL BROADCAST: November 8, 2019 NOTE: This is a transcription of the spoken dialogue and audio, with time-code reference, provided without cost by 8FLiX.com for your entertainment, convenience, and study. This version may not be exactly as written in the original script; however, the intellectual property is still reserved by the original source and may be subject to copyright. EPISODE CAST Brenton Thwaites ... Dick Grayson Teagan Croft ... Rachel Roth Ryan Potter ... Gar Logan Conor Leslie ... Donna Troy Joshua Orpin ... Conner Evan Jones ... Len Armstrong Orel De La Mota ... Rafael Julian Works ... Luis Reynaldo Gallegos ... Santos Natalie Gumede ... Mercy Graves Raoul Bhaneja ... Walter Hawn Delia Lisette Chambers ... Daughter #1 Lyla Elliott ... Daughter #2 Jillian Niedoba ... Mercy's Wife Sydney Kuhne ... Dani Ish Morris ... Caleb Michael Reventar ... Carlos Tameka Griffiths ... Eriel Nicky Lawrence ... Soup Kitchen Employee Patrick Haye ... Guard 1 Ahmed Moustafa ... Police Officer P a g e | 1 1 00:00:12 --> 00:00:14 [Rachel] Previously on Titans... 2 00:00:14 --> 00:00:17 I lied. I told you that Jericho was dead when I got to the church. 3 00:00:17 --> 00:00:18 He died trying to save me from his father. 4 00:00:18 --> 00:00:20 [grunts] 5 00:00:20 --> 00:00:21 You lying sack of shit. -

MADE in PRISON Front Cover

MADE IN PRISON Front Cover: Welmon Sharlhorne, Untitled, n.d., pen and marker on board, 22” x 28” Prison architecture, dragons, birds and clocks are recurring images in the work of Welmon Sharlehorne, who uses these symbols to represent his experiences as an inmate in the Louisiana prison system. The fantastic-geometric style and radial patterns that distinguish Sharlhorne’s drawings are made using jar lids and bottle tops of various sizes. MADE IN PRISON CONTEMPORARY ART BY INCARCERATED MEN AND WOMEN Co-curated and with an introduction by Julia Dzwonkoski and Kye Potter Essay by Jean Gregorek November 7, 2003 - February 6, 2004 Herndon Gallery Antioch College Yellow Springs, Ohio ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank the artists for their sharing their incredible work with us. We also wish to thank the friends and families of participating artists, especially Marge Satterlee, Janine Tucker, Roberta Rogers, the Fasslers, the McCurdys, Kris Hammond and Rose Leining. Thanks to the following individuals for their generosity and insight: Buzz Alexander, Janie Paul, Jesse Jannetta, Phyllis Kornfeld, Rebecca Boyden, Jeffrey Greene, Barbara Hirshkowitz, Darcy Hirsh, and Stephen Canneto. Ms. Thomas, Mr. Scott and Mr. Chavez from the Dayton Correctional Institution also deserve our thanks. Thanks to the American Visionary Art Museum, especially Mark Ward and Sarah Templin, and to Phyllis Kornfeld, Community Partners in Action, the Contexts Collection of Book Through Bars, Jeffrey Greene, ArtSafe, Phyllis Kind Gallery, American Primitive Gallery, The Fortune Society and Michael and Ina Wesenberg for loaning works to this exhibition. Thanks are also due to many people here in Yellow Springs: to Jean Gregorek for her timely and illuminating essay; Chris Hill, Brian Springer, and Dennie Eagleson for their thoughtful feedback and support; and Herndon staff members Crystal Kelliher, Trish Donaldson, Kyle McCann, Jessica Smith, Justin Price, and Mo Modano. -

Marvin Country Lyrics

Marvin Country lyrics: YOU POSSESS ME (marvin etzioni) i have found a place in the circle of your arms my world is now safe from the sirens and alarms you possess me you possess me like no one ever has like no one ever will i look in your eyes shining in the dark i am hypnotized you control my heart you possess me you possess me like no one ever has like no one ever will i’m not over i’m under your spell am i sober? i’m so in love i cannot tell i can now embrace what i could never touch your innocence and grace are like the heartbeat of a dove you possess me you possess me like no one ever has like no one ever will like no one ever has like no one ever will THE GRAPES OF WRATH (marvin etzioni) you can’t hold me to what you’re thinking/ you can’t hold me i’m not the bottle you’re drinking/ you broke my heart in half now its time for you to taste/ the grapes of wrath/ you can’t tell me the taste is bitter/ you can’t tell me its getting better you broke my heart in half/ now it’s time for you to taste/ the grapes of wrath you have changed i’ve changed too/ there’s a price to pay for hurting this one too you got a heart of stone/ you got eyes like steel/ you got two hands that touch/ but you’re too crippled to feel you broke my heart in half/ now it’s time for you to taste/ the grapes of wrath please don’t hold me like you’re doing/ please don’t kiss me/ ‘cause it’s too confusing you broke my heart in half/now it’s time for you to taste/ yeah it’s time for you to taste/ it’s time for you to taste the grapes of wrath YOU ARE THE LIGHT (marvin -

Karaoke Songlist

KARAOKE SONGLIST DESUCON KARAOKE SPONSORED BY: Joensuun Otakut (Jotkut) http://jotkut.animeunioni.org Asian Kung-fu Generation - After Dark JAPANILAISET / (FULL+TV) Aya Hirano - God Knows (FULL+TV) JAPANESE Aya Hirano - God Knows (eurobeat) Ayya Hirano - God Knows - Violin & Piano Merkkien selitykset remix (INSTRU) FULL = Koko versio Aya Hirano - Lost My Music (FULL+TV) TV = TV versio Aya Matsuura - Good Bye Natsuo INSTRU = Instrumentaali Aya Matsuura - LOVE Namida Iro Aya Matsuura - Yeah Meccha Holiday Mark explanations: Ayaka - Okeari (Zettai Kareshi) FULL = Full version Ayaka - Why TV = TV version Ayumi Hamasaki - Angel's Song INSTRU = Instrumental Ayumi Hamasaki - appears Ayumi Hamasaki - Boys & Girls A Ayumi Hamasaki - CAROLS Abingdon Boys School - HOWLING Ayumi Hamasaki - Connecter (FULL+TV) Ayumi Hamasaki - Dearest Abingdon Boys School - Innocent Sorrow Ayumi Hamasaki - Evolution (FULL+TV) Ayumi Hamasaki - For My dear Ah! My Goddess - Omedeto! Ayumi Hamasaki - Raindow Ai Otsuka - Sakuranbo Ayumi Hamasaki - Rule Ai Otsuka - Sakuranbo (short remix) Ayumi Hamasaki - SEASONS Air - Tori no Uta (TV) Ayumi Hamasaki - Sparkle Akeboshi - Win (FULL+TV) Akeboshi - Yellow Moon (FULL+TV) B Ali Project - Kinjireta Asobi (TV) BAAD - Kimi ga suki da to sakebai (TV) Alüto - Michi ~to you all~ Bana - Shell (FULL+TV+INSTRU) Bana - Half Pain ANNA 'inspi NANA ~BLACK STONES~ - Beat Crusaders - tonight, tonight, tonight Kuroi Namida (FULL+TV) (FULL+TV) ANNA 'inspi NANA ~BLACK STONES~ - Beck - Hit in the USA Lucy (FULL+TV) Berryz Koubou - Gag 100kaibun -

Deviance and Devotion-Final

!1 Deviance and Devotion: On the Social Subversions of Young Korean Women as Sasaeng Fans Ida Bulölö 10216898 Supervised by Dr. O.K. Sooudi Contemporary Asian Studies Thesis Graduate School of Social Science University of Amsterdam 27.06.2016 !2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank everyone who has guided and aided me in the writing of this thesis. My research would not have been possible without help from many people in Korea and I would like to specifically thank Jiye Oh for helping me with translations and dissecting the research process with me, Chana Lee for all her fan wisdom and general help, Professor Hyun Mee Kim for giving me the opportunity to speak to her and present my research to her class, Jungwon Kim for bringing me to the hidden-away places and her knowledge, Jihyun Jang, Soohee Lee and Jini for their time, research skills and help. I would like to thank Olga Sooudi for her supervision during this process and Tina Harris for her additional comments on my work. I would like to give a shoutout to Veerle Boekestijn for designing the beautiful cover page. I am much indebted to Shai Simpson-Baikie for her great advice. I am grateful for my parents for giving me the opportunity to pursue the things I value. Lastly, I want to thank my partner for his patience and support. I dedicate this thesis to Tante Hemi Oom Roel !3 Table of Contents Index of Idols 4 Graphs of Fan Hierarchy 5 Table of Research Activity 6 Introduction 7 1. -

Url 430 Run Fty12001 Dvd Ot

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマットジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 430 RUN FTY12001 DVD OTHER DVD 2,314 https://tower.jp/item/3141062 2700 2700 NEW ALBUM ラストツネミチ-ヘ長調- YRBN90516 DVD OTHER DVD 2,857 https://tower.jp/item/3205636 (スポーツ・野球) WORLD BASEBALL CLASSIC プレミアムBOX DEWBC1 DVD OTHER DVD 12,000 https://tower.jp/item/2161881 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 100% (Korea) How to cry (ミヌ盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5005 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415958 100% (Korea) How to cry (ロクヒョン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5006 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415970 100% (Korea) How to cry (ジョンファン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5007 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415972 100% (Korea) How to cry (チャンヨン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5008 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415974 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you (A) OKCK5011 Single K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655024 100% (Korea) Song for you (B) OKCK5012 Single K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655026 100% (Korea) Song for you (C) OKCK5013 Single K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655027 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4655033