TICL Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phase II Investigation Was Completed in 2005

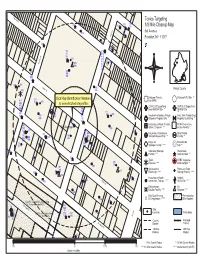

Wa rren St Toxics Targeting 133 339 130 129 131 132 1/8 Mile Closeup Map e v 127 3rd Avenue 419 A d r 128 3 Brooklyn, NY 11217 420 338 340 74 414 88 415 t 89 416 S s 90 371 413 in 20 v 412 376 Ne 425 118 426 117 333 417 396 394 405 395 116 121 381 Ba 392 ltic Kings County 422 St 393 Click Map Identification Numbers National Priority Delisted NPL Site ** 411 113 List (NPL) * 408 114 369 to view detailed site profiles 410 CERCLIS Superfund CERCLIS Superfund 409 384 Non-NFRAP Site ** NFRAP Site 407 383 48 111 ** 331 388 382 87 370 332 399 389 322 Inactive Hazardous Waste Inact. Haz Waste Disp. 400 110 Disposal Registry Site * Registry Qualifying * 109 60 330 Hazardous Waste Treater, RCRA Corrective 328 3rd Avenue 398 Storer, Disposer ** Action Facility * 329 373 58 84 120 75 391 365 Hazardous Substance Solid Waste 115 363 73 364 Waste Disposal Site ** Facility ** 326 404 324 362 85 403 327 423 Major Oil Brownfields 378 112 386 377 385 387 Storage Facility **** Site ** 122 Chemical Storage Hazardous Facility **** Material Spill ** 323 372 123 Toxic MTBE Gasoline 375 Release **** Additive Spill ** 374 367 390 Wastewater Petroleum Bulk 86 366 427 325 Discharge **** Storage Facility **** 424 92 Hazardous Waste Historic 402 368 Bu Generator, Transp. **** Utility Site **** tler 397 St Enforcement Air Docket Facility **** Release **** 401 Env Qual Review Remediation 406 E Designation ***** Site Borders C224051 - Brownfield Cleanup Prog 119 De K - Fulton Municipal MGP 16 G 334 raw 335 St Site 91 e 23 v A Location Waterbody 336 380 418 4 224051 - Hazardous Waste h 337 t 421 21 K - Fulton Works 379 4 22 County Railroad Doug Border Tracks lass S t 1/8 Mile 250 Foot Radius Radius 93 * 1 Mile Search Radius ** 1/2 Mile Search Radius 1/8 0 1/16 1/8 **** 1/8 Mile Search Radius ***** Onsite Search (250 Ft) Distance in Miles LIMITED WARRANTY AND DISCLAIMER OF LIABILITY Who is Covered This limited warranty is extended by Toxics Targeting, Inc. -

Manhattan Resolution Date: September 27, 2011

COMMUNITY BOARD #1 – MANHATTAN RESOLUTION DATE: SEPTEMBER 27, 2011 COMMITTEE OF ORIGIN: BATTERY PARK CITY COMMITTEE VOTE: 6 In Favor 0 Opposed 0 Abstained 0 Recused PUBLIC MEMBERS: 2 In Favor 0 Opposed 1 Abstained 0 Recused BOARD VOTE: 39 In Favor 0 Opposed 0 Abstained 0 Recused RE: Additional West Thames Park lawn usage rules and guidelines WHEREAS: West Thames Park should be well maintained to preserve its longevity; and WHEREAS: The West Thames Park lawn was designed as a community “back yard”, and contemplated as an informal play area for school-age children and other light- impact recreational uses; and WHEREAS: A few simple rules can be implemented to prevent the overuse of the West Thames Park field and maintain a family friendly atmosphere; now THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED THAT: Community Board #1 recommends that the Battery Park City Authority adopt, publically post and enforce the following rules with regard to the West Thames Park lawn: 1) No cleats allowed on the lawn. 2) No one group of people may use more than half the lawn. 3) Play should not be so aggressive as to pose the unreasonable risk of harm to other users. BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED THAT: Community Board #1 recommends that the Battery Park City Authority not issue any permits for athletic league use of the West Thames Park lawn for the next twelve months, and to evaluate, with the Battery Park City Committee, the issue of athletic league permitting at the end of this twelve month period. COMMUNITY BOARD #1 – MANHATTAN RESOLUTION DATE: SEPTEMBER 27, 2011 COMMITTEE OF ORIGIN: -

NYS Certified MWBE's Contact List

NYS Certified MWBE 's Contact List 3/29/2011 1 Company Name M/WBE LastName First Name Title Phone Email Address City ST Zip Capabilities 781-891-3300 134 West 29th Street New York NY 10001 VoIP and Video Network Assessments, CDR Analysis and Reporting, Advanced Abacus Group, Inc. W Mulloy Mary Pres. 617-489-0200 [email protected] 13 Falmonth Heights Rd. Falmonth MA 02540 ACD Reporting, Voice Recording, Open Source Telephony Consulting 185 Van Rensselaer Blvd. IT staffing, Data storage architecture, design and implementation, Remote online ACube Consulting, Inc M Ahmed Azim Pres. 518-331-3636 [email protected] 2-2B Albany NY 12204 backup/recovery services, Server, desktop, peripheral installation services Medical Archiving Solutions; Media creation and distribution solutions; nComputing solutions for PC consolidation; Data Security solutions; HP Enterprise solutions, servers and storage and HP printers; Emergency Notification consulting services; telecommunications from Alcatel Lucent; consulting services Affinity Enterprises, LLC W Hylant Peg Pres. 518-693-6344 [email protected] 116 East Ave Saratoga Springs NY 12866 for HP platforms and other solution providers. Albany Information Technology Software Development Team Leadership, Custom Software Development from Group, LLC M Woytowich Michael Pres. 518-633-1864 [email protected] 376 Broadway Suite 17 Saratoga Springs NY 12866 requirements through implementation CSCIC Compliance, Risk Assessments, Remediation Plans, Security Policies, information Security Risk Analysis, Reporting & Compliance, IT Project Allen Associates W Allen Mary Beth President 518-482-1431 [email protected] 352 Manning Blvd Albany NY 12206 Management 12047- IT, Business Intelligence, Data Warehousing, Project Management & Business Alternative Insights, Inc. W Smith Susan Pres. -

Procurement Report

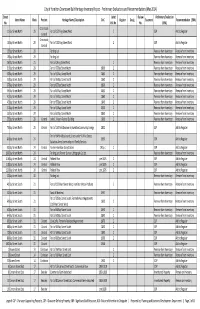

Procurement Tranactions Bulk Load Worksheet Version 1.8 Procurement Transaction In accordance with Sections 2879 and 2824(e) of the Public Authorities Law, please provide the following information on each procurement contract that was active (open) at any time during the reporting period: Columns whose names contain "*" are required and must have values for each record to be loaded. Do not enter blank lines, as a blank line (a line with no information) will be regarded as the end of the fil This worksheet must be saved as type "csv" in order to be uploaded to PARIS. Select "Save As" from the "File" menu above and select "CSV (comma delimited)" as the file type. Note: Most cells have some level of validation, however, validation in Excel only functions when you actually type data in the cell. It is recommended that you selectively check validation in rows that you have copied data into. ----------------------------------------Vendor Address -------------------------------------------------------------- Exempt from the Number of Is the Is the Number of publication Bids or Vendor a Vendor a Were MWBE bids or requirements Explain why the Proposals NYS or Minority or firms proposals of Article 4c fair market Received Foreign Woman- solicited as received of the value is less Does the * Amount Amount Current or Prior to Business Owned part of this from economic than the Transaction Award Begin Renewal contract have Expended For Expended For Outstanding Award of Enterprise Business procurement MWBE development Fair Market contract * Postal Province/ Country Name if * Vendor Name Number * Procurement Description * Status * Type of Procurement * Award Process Date Date Date an end Date? End Date Amount Fiscal Year Life To Date Balance Contract ? Enterprise? process? firms. -

TICL Journal

TICL Journal Volume 31, No. 2 Fall 2002 Issue Copyright 2002 by the New York State Bar Association ISSN 1530-390X TORTS, INSURANCE AND COMPENSATION LAW SECTION EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE—2002-2003 SECTION CHAIR NINTH DISTRICT Dennis R. McCoy THIRD DISTRICT Thomas J. Burke 1100 M&T Center Edward B. Flink 10 Bank Street, Suite 1040 Three Fountain Plaza 7 Airport Park Boulevard White Plains, NY 10606 Buffalo, NY 14203 Latham, NY 12110 Hon. Anthony J. Mercorella 150 East 42nd Street VICE-CHAIR Christine K. Krackeler New York, NY 10017 Eric Dranoff 16 Sage Estate 331 Madison Avenue Menands, NY 12204 New York, NY 10017 TENTH DISTRICT FOURTH DISTRICT James J. Keefe, Jr. SECRETARY Paul J. Campito 1140 Franklin Avenue Eileen E. Buholtz 131 State Street P.O. Box 7677 250 Times Square Building P.O. Box 1041 Garden City, NY 11530 45 Exchange Street, Suite 250 Schenectady, NY 12305 Rochester, NY 14614 Arthur J. Smith Robert P. McNally 125 Jericho Turnpike Jericho, NY 11753 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 175 Ottawa Street Lake George, NY 12845 LIAISON ELEVENTH DISTRICT Edward S. Reich Edward H. Rosenthal 26 Court Street, Suite 606 FIFTH DISTRICT 125-10 Queens Boulevard Brooklyn, NY 11242 Timothy J. Fennell 26 East Oneida Street Kew Gardens, NY 11415 Oswego, NY 13126 DELEGATES TO THE TWELFTH DISTRICT HOUSE OF DELEGATES Lori E. Petrone Mitchell S. Cohen Louis B. Cristo 1624 Genesee Street 116 John Street, 33rd Floor 700 Reynolds Arcade Utica, NY 13502 New York, NY 10038 16 East Main Street Rochester, NY 14614 SIXTH DISTRICT Robert S. Summer John J. Pollock 714 East 241st Street Edward B. -

Manhattan Community Board 1 Full Board Meeting

Manhattan Community Board 1 Full Board Meeting TUESDAY, APRIL 28, 2015 6:00 PM Southbridge Towers 90 Beekman Street Community Room Catherine McVay Hughes, Chairperson Noah Pfefferblit, District Manager Lucy Acevedo, Community Coordinator Tamar Hovsepian, Community Liaison Diana Switaj, Director of Planning and Land Use Michael Levine, Planning Consultant Manhattan Community Board 1 Public Session Comments by members of the public (6 PM to 7 PM) (Please limit to 1-2 minutes per speaker, to allow everyone to voice their opinions) Guest Speaker: Captain Mark Iocco, Commanding Officer, New York Police Department 1st Precinct Manhattan Community Board 1 Business Session • Adoption of March 2015 minutes • Chairperson’s Report – C. McVay Hughes • District Manager’s Report – N. Pfefferblit • Treasurer’s Report – J. Kopel (Postponed until May 2015) Battery Park – portions of the fence are down to open up park and bike path near Pier A (04/17/15) WTC Calatrava PATH Station Tour – with CB1 Planning and PANYNJ (04/07/15) Working Group Session with Legends at the 1 WTC Observatory – with CB1 Planning and Executive Committees and PANYNJ (04/23/15) Photos: B. Scheck James Zadroga NYC Council Resolution – joined NYC Council Member Chin, Mariama James and others to celebrate vote on resolution calling on Congress to reauthorize the James Zadroga 9/11 Act which provides vital health treatment and compensation to 9/11 survivors and first responders (City Hall Steps, 04/16/15) Manhattan Community Board 1 Population Change Update #2 School Overcrowding Task Force April 15, 2015 Jeff Sun Community Planning Fellow Supervised by Diana Switaj Director of Planning & Land Use Manhattan Community Board 1 Population Change Analysis Methodology Notes: * Residential units count tabulated by CB 1 from 2012 to 2016 and beyond. -

JOHN THOMPSON Managing Director

NEW YORK, NY JOHN THOMPSON Managing Director PROFILE John Thompson is a managing director in the New York office of Lee & Associates. He specializes in office leasing for both landlords and tenants. CAREER SUMMARY Mr. Thompson joined Lee & Associates NYC in 2019. He has over 35 years of experience in office leasing and commercial real estate advisory roles at the industry’s leading firms. O 212.776.4354 C 914.525.0232 With extensive experience on both sides of commercial real estate transactions, Mr. Thompson has represented an array of corporate clients jthompson@ as well as many prominent Manhattan office buildings. He has advised lee-associates.com clients on assignments involving brokerage, property acquisitions and lee-associates.com dispositions, and property management. Most recently, Mr. Thompson 845 Third Avenue oversaw the leasing of 116 and 85 John Street in Lower Manhattan. He has also represented major corporations such as Barclays Bank, MCI, 4th Floor Metropolitan Life, Hallmark Cards, and Viacom. New York, NY 10022 Prior to joining Lee & Associates NYC, Mr. Thompson had worked at Douglas Elliman Commercial, was a managing director at Galbreath Company, and an assistant vice president at Cross & Brown in its leasing and sales division. Mr. Thompson began his real estate career at Cushman PARTIAL CLIENT LIST & Wakefield. • Barclays Bank • MCI EXPERIENCE • Metropolitan Life • 2019 to present: Managing Director, Lee & Associates • Hallmark Cards • 2015 to 2019: Senior Broker, Douglas Elliman Commercial • Viacom EDUCATION LEASING AGENT • Bachelor’s Degree in Economics, Union College • 85 John Street • Licensed to practice real estate in the state of New York • 111 John Street • 116 John Street COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT • 67 Broad Street • Member, Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY) • 315 Park Avenue South • 140 East 45th Street • 540 Madison Avenue • 1633 Broadway • The Falchi Building – 31-00 47th Avenue, Long Island City . -

Downtown Built Heritage Inventory List

City of Hamilton Downtown Built Heritage Inventory Project ‐ Preliminary Evaluations and Recommendations (May 2014) Street Listed By‐Law Preliminary Evaluation Street Name Block Precinct Heritage Name/ Description DoC Register Desig. Easement Recommendation (ERA) No. Vol. No. No. (ERA) Crossroads; 11 Bay Street North 29 Part of 152 King Street West 2 CSP Add to Register Central Crossroads; 13 Bay Street North 29 Part of 152 King Street West 2 CSP Add to Register Central 15 Bay Street North 29 Parking Lot Remove from Inventory Remove from Inventory 19 Bay Street North 29 Parking Lot Remove from Inventory Remove from Inventory 26 Bay Street North 21 Part of 2 King Street West 2 Remove from Inventory Remove from Inventory 31 Bay Street North 29 Part of 55 Bay Street North 1860 2 Remove from Inventory Remove from Inventory 33 Bay Street North 29 Part of 55 Bay Street North 1860 2 Remove from Inventory Remove from Inventory 35 Bay Street North 29 Part of 55 Bay Street North 1860 2 Remove from Inventory Remove from Inventory 37 Bay Street North 29 Part of 55 Bay Street North 1860 2 Remove from Inventory Remove from Inventory 39 Bay Street North 29 Part of 55 Bay Street North 1860 2 Remove from Inventory Remove from Inventory 41 Bay Street North 29 Part of 55 Bay Street North 1860 2 Remove from Inventory Remove from Inventory 45 Bay Street North 29 Part of 55 Bay Street North 1840 2 Remove from Inventory Remove from Inventory 51 Bay Street North 29 Part of 55 Bay Street North 1900 2 Remove from Inventory Remove from Inventory 53 Bay Street North 29 Part of 55 Bay Street North 1860 2 Remove from Inventory Remove from Inventory 55 Bay Street North 29 Central John C. -

Manhattan Office Market

Manhattan Offi ce Market 3 RD QUARTER 2019 REPORT A NEWS RECAP AND MARKET SNAPSHOT Pictured: 380 Second Avenue Looking Ahead New Letter-Grade Energy Ratings Requirement for NYC Buildings The bill proposed in 2017 as part of a “package of quality-of-life” measure was reportedly enacted by Mayor de Blasio on January 8, 2018. Local Law 33 is the latest initiative to reduce greenhouse emissions and increase the energy effi ciency of large and mid-sized New York City buildings. Beginning January 2020, city-owned buildings larger than 10,000 square feet and all other commercial and residential buildings over 25,000 square feet will be required to display energy effi ciency grades near a public entrance, reportedly expanding upon Local 84 of 2009, which requires the submission of annual energy and water consumption benchmark data. Ranging from “A” to “F,” the letter grades will be based on the United States Department of Energy’s Energy Star score. Rating Required Score Rating Required Score “A” 85 or higher “C” 55 or higher “B” 70 or higher “D” Less than 55 “F” if information not submitted by owner to the city “N” if not feasible to obtain a score, however the city plans to audit the information submitted for the ranking Response to the new law has been mixed, with some suggesting last year that the “system may need to provide exemptions for those buildings with historical designations that may be prohibited from completing certain upgrades.” Proponents of the bill believe it will help push the city’s building owners to reduce energy usage and carbon emissions as intended. -

An Insurer's Right of Subrogation in New York

TICL Journal Volume 31, No. 1 Spring 2002 Issue Copyright 2002 by the New York State Bar Association ISSN 1530-390X TORTS, INSURANCE AND COMPENSATION LAW SECTION EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE—2002-2003 SECTION CHAIR THIRD DISTRICT Hon. Anthony J. Mercorella Dennis R. McCoy Edward B. Flink 150 East 42nd Street 1100 M&T Center 7 Airport Park Boulevard New York, NY 10017 Three Fountain Plaza Latham, NY 12110 Buffalo, NY 14203 TENTH DISTRICT Christine K. Krackeler James J. Keefe, Jr. 16 Sage Estate VICE-CHAIR 1140 Franklin Avenue Menands, NY 12204 Eric Dranoff P.O. Box 7677 331 Madison Avenue Garden City, NY 11530 New York, NY 10017 FOURTH DISTRICT Paul J. Campito Thomas J. Spellman, Jr. SECRETARY 131 State Street 50 Route 111 Hillside Village Plaza Eileen E. Buholtz P.O. Box 1041 Smithtown, NY 11787 250 Times Square Building Schenectady, NY 12305 45 Exchange Street, Suite 250 Rochester, NY 14614 Robert P. McNally ELEVENTH DISTRICT P.O. Box 2017 Edward H. Rosenthal Glens Falls, NY 12801 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 125-10 Queens Boulevard Kew Gardens, NY 11415 LIAISON FIFTH DISTRICT Edward S. Reich Timothy J. Fennell Arthur J. Smith 26 Court Street, Suite 606 26 East Oneida Street 125 Jericho Turnpike Brooklyn, NY 11242 Oswego, NY 13126 Jericho, NY 11753 DELEGATES TO THE Lori E. Petrone TWELFTH DISTRICT HOUSE OF DELEGATES 1624 Genesee Street Mitchell S. Cohen William N. Cloonan Utica, NY 13502 116 John Street, 33rd Floor 85 Main Street New York, NY 10038 Kingston, NY 12401 SIXTH DISTRICT John J. Pollock Robert S. Summer Edward B. Flink P.O. -

Be in Accord with Liberty Island Preservation Planning Documents • Work Collaboratively with Our Nonprofit Foundation Partner

Manhattan Community Board 1 Full Board Meeting Thursday, December 17, 2015 6:00 PM South Street Seaport Museum Melville Gallery 213 Water Street Catherine McVay Hughes, Chairperson Noah Pfefferblit, District Manager Lucy Acevedo, Community Coordinator Diana Switaj, Director of Planning and Land Use Michael Levine, Planning Consultant CB1's OFFICE HAS MOVED Please update your records to reflect the following changes: Manhattan Community Board 1 1 Centre Street, Room 2202 North New York, NY 10007 Tel: (212) 669-7970 Fax: (212) 669-7899 Website: http://www.nyc.gov/html/mancb1/html/ho me/home.shtml Email: [email protected] Manhattan Community Board 1 Public Session Comments by members of the public (6 PM to 7 PM) (Please limit to 1-2 minutes per speaker, to allow everyone to voice their opinions) Welcome Captain Jonathan Boulware, Executive Director, South Street Seaport Museum Manhattan Community Board 1 Business Session • Adoption of November 2015 minutes • Chairperson’s Report – C. McVay Hughes • District Manager’s Report – N. Pfefferblit Senators, Congress Members Announce Renewal of Zadroga 9/11 Health and Compensations Programs to be Included in Final Omnibus Spending Bill December 15, 2015 Rachel Maddow Show December 16, 2015 Renewal of Zadroga 9/11 Health & Compensation Programs Sign installed for Spruce Street School Beekman Street light fixed, working on paving and striping Bikeway-walkway has reopened from Vesey though Liberty Streets on the west side of Route 9A and Fulton Street NYC Rescue Mission and volunteers, including from Chinatown and Community Board 1, prepared a feast for hundreds of men, women and children from low income communities and shelters across New York City (11/27/15) Manhattan Community Board 1 Committee Reports Personnel – S. -

ATTACHMENT B Section II. Property Information

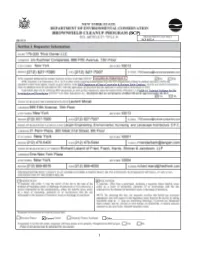

ATTACHMENT A Section I. Requestor Information NYS Department of State’s Corporation and Business Entity Database Entity Information for 175-225 Third Owner LLC Brownfield Cleanup Program Application Attachment A 225 3rd Street Brooklyn, NY ATTACHMENT A SECTION I: REQUESTOR INFORMATION A copy of the entity information from the NYS Department of State’s Corporation & Business Entity Database is included with this attachment. Pursuant to ECL § 27-1405(1), 175-225 Third Owner LLC is properly designated as a Volunteer because its liability arises solely from involvement with the site after the release/discharge and because it has taken appropriate care to stop any continuing release, to prevent any threatened future release, and to prevent or limit human, environmental or natural resource exposures to any previously released hazardous waste. 1 Entity Information Page 1 of 2 NYS Department of State Division of Corporations Entity Information The information contained in this database is current through January 7, 2015. Selected Entity Name: 175-225 THIRD OWNER LLC Selected Entity Status Information Current Entity Name: 175-225 THIRD OWNER LLC DOS ID #: 4680242 Initial DOS Filing Date: DECEMBER 15, 2014 County: NEW YORK Jurisdiction: DELAWARE Entity Type: FOREIGN LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY Current Entity Status: ACTIVE Selected Entity Address Information DOS Process (Address to which DOS will mail process if accepted on behalf of the entity) NATIONAL REGISTERED AGENTS, INC. 111 EIGHTH AVENUE NEW YORK, NEW YORK, 10011 Registered Agent NATIONAL REGISTERED AGENTS, INC. 111 EIGHTH AVENUE NEW YORK, NEW YORK, 10011 This office does not require or maintain information regarding the names and addresses of members or managers of nonprofessional limited liability companies.