TICL Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FLI Schedules - 1-16-07 in Re: FABRIKANT-LEER INTERNATIONAL, LTD., Debtor

United States Bankruptcy Court Southern District of New York In re: FABRIKANT-LEER INTERNATIONAL, LTD., Debtor. Case No. 06-12739 (SMB) Chapter 11 SUMMARY OF SCHEDULES Indicate as to each schedule whether that schedule is attached and state the number of pages in each. Report the totals from Schedules A, B, D, E, F, I, and J in the boxes provided. Add the amounts of all claims from Schedules A and B to determine the total amount of the debtor’s assets. Add the amounts of all claims from Schedules D, E, and F to determine the total amount of the debtor’s liabilities. Individual debtors must also complete the “Statistical Summary of Certain Liabilities and Related Data” if they file a case under chapter 7, 11, or 13. ATTACHED NO. OF NAME OF SCHEDULE ASSETS LIABILITIES OTHER (Yes/No) SHEETS A - Real Property Yes 1 $ 0 B - Personal Property Yes 4 149,451,077 C - Property Claimed as Exempt Yes 1 D - Creditors Holding Secured Claims Yes 1 $ 161,947,902 E - Creditors Holding Unsecured Priority Claims (Total of Claims of Yes 2 390,177 Schedule E) F - Creditors Holding Unsecured Yes 2 119,861,635 Non Priority Claims G - Executory Contracts and Yes 1 Unexpired Leases H - Codebtors Yes 1 I - Current Income of Individual Debtor(s) Yes 1 N/A J - Current Expenditures of Individual Yes 1 N/A Debtor(s) TOTAL 15 $149,451,077.20 $282,199,714.42 FLI Schedules - 1-16-07 In re: FABRIKANT-LEER INTERNATIONAL, LTD., Debtor. Case No. 06-12739 (SMB) Chapter 11 SCHEDULE A - REAL PROPERTY Except as directed below, list all real property in which the debtor has any legal, equitable, or future interest, includingall property owned as a co-tenant, community property, or in which the debtor has a life estate. -

The New Executive Offices Represent the New Standard for Boutique Office Space in New York City

The new Executive Offices represent the new standard for boutique office space in New York City. The entry features an iconic 93-foot glass totem that reflects the spirit and design of the soaring 96-story residential tower at 432 Park Avenue. The offices are exceptionally spacious, with large column-free spans, flexible floor plates and ceiling heights of more than fifteen feet. Uninterrupted floor-to-ceiling windows allow for an abundance of natural light to illuminate each space. Strong, expansive and sleek, the floors offer the highest-quality office space for the most demanding tenants. 432 Park Avenue Executive Offices & Retail Entry Diagram Angled Entry & Iconic Glass Totem Private Lobby Angled Entry & Iconic Glass Totem Reception Private Corner Office Analysts/Trading Conference Room Collaborative Seating Area Analysts/Trading/Support Abundant Natural Light 12'-6" 15'-6" Vision Finished Slab to Slab Glass Ceiling Height 9'-0" 10'-6" Vision Finished Slab to Slab Glass Ceiling Height 432 Park Avenue Executive Offices Traditional Office Typical Section at Curtain Wall Typical Section at Curtain Wall with Perimeter PTAC Building Facts Location Floor Sizes Electrical Located at the base of 432 Park 4 levels of 17,600+ RSF per floor Approximately 12 watts per sq ft Avenue Tower, the Western exclusive of base building load; 460 Hemisphere’s tallest residential Finished Ceiling Heights volt, 3 phase main service with building at 1,396' tall 12'-6" redundant Con Edison feeds Design Slab to Slab Heights HVAC Iconic entry design with 93' tall cut 15'-6" Roof mounted 675 ton cooling tower out and glass totem for condenser water system dedicated Column Spacing Modern private lobby featuring for commercial/retail units. -

United States Securities and Exchange Commission Form

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): June 6, 2008 BOSTON PROPERTIES LIMITED PARTNERSHIP (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 0-50209 04-3372948 (State or other jurisdiction (Commission File Number) (IRS Employer of incorporation) Identification No.) 800 Boylston Street, Suite 1900, Boston, Massachusetts 02199-8103 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (617) 236-3300 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions (see General Instruction A.2. below): ☐ Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) ☐ Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Item 1.01. Entry into a Material Definitive Agreement. Item 2.03. Creation of a Direct Financial Obligation or an Obligation under an Off-Balance Sheet Arrangement of a Registrant. On June 6, 2008, Boston Properties Limited Partnership (the “Company”) a Delaware limited partnership and the entity through which Boston Properties, Inc. conducts substantially all of its business, utilized an accordion feature under its Fifth Amended and Restated Revolving Credit Agreement with a consortium of lenders to increase the current maximum borrowing amount under the facility from $605 million to $923.3 million, and the Company expects to further increase the maximum borrowing amount to $1 billion in the near future. -

Phase II Investigation Was Completed in 2005

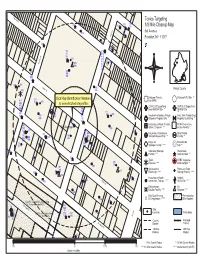

Wa rren St Toxics Targeting 133 339 130 129 131 132 1/8 Mile Closeup Map e v 127 3rd Avenue 419 A d r 128 3 Brooklyn, NY 11217 420 338 340 74 414 88 415 t 89 416 S s 90 371 413 in 20 v 412 376 Ne 425 118 426 117 333 417 396 394 405 395 116 121 381 Ba 392 ltic Kings County 422 St 393 Click Map Identification Numbers National Priority Delisted NPL Site ** 411 113 List (NPL) * 408 114 369 to view detailed site profiles 410 CERCLIS Superfund CERCLIS Superfund 409 384 Non-NFRAP Site ** NFRAP Site 407 383 48 111 ** 331 388 382 87 370 332 399 389 322 Inactive Hazardous Waste Inact. Haz Waste Disp. 400 110 Disposal Registry Site * Registry Qualifying * 109 60 330 Hazardous Waste Treater, RCRA Corrective 328 3rd Avenue 398 Storer, Disposer ** Action Facility * 329 373 58 84 120 75 391 365 Hazardous Substance Solid Waste 115 363 73 364 Waste Disposal Site ** Facility ** 326 404 324 362 85 403 327 423 Major Oil Brownfields 378 112 386 377 385 387 Storage Facility **** Site ** 122 Chemical Storage Hazardous Facility **** Material Spill ** 323 372 123 Toxic MTBE Gasoline 375 Release **** Additive Spill ** 374 367 390 Wastewater Petroleum Bulk 86 366 427 325 Discharge **** Storage Facility **** 424 92 Hazardous Waste Historic 402 368 Bu Generator, Transp. **** Utility Site **** tler 397 St Enforcement Air Docket Facility **** Release **** 401 Env Qual Review Remediation 406 E Designation ***** Site Borders C224051 - Brownfield Cleanup Prog 119 De K - Fulton Municipal MGP 16 G 334 raw 335 St Site 91 e 23 v A Location Waterbody 336 380 418 4 224051 - Hazardous Waste h 337 t 421 21 K - Fulton Works 379 4 22 County Railroad Doug Border Tracks lass S t 1/8 Mile 250 Foot Radius Radius 93 * 1 Mile Search Radius ** 1/2 Mile Search Radius 1/8 0 1/16 1/8 **** 1/8 Mile Search Radius ***** Onsite Search (250 Ft) Distance in Miles LIMITED WARRANTY AND DISCLAIMER OF LIABILITY Who is Covered This limited warranty is extended by Toxics Targeting, Inc. -

Commercial and Federal Litigation Section Newsletter a Publication of the Commercial and Federal Litigation Section of the New York State Bar Association

NYSBA FALL 2001 | VOL. 7 | NO. 1 Commercial and Federal Litigation Section Newsletter A publication of the Commercial and Federal Litigation Section of the New York State Bar Association A Message from the A Message from the Outgoing Chair Incoming Chair I welcome the opportunity, As your incoming Chair, I through this newsletter, to keep want to share with you the the 1,800 Section members excitement I feel about our Sec- informed about Section news tion in the coming year. Thanks and provide information that is to the groundwork done by helpful in daily practice, as the Sharon Porcellio, the Section is dedicated and energetic 2001- in its strongest position in years. 2002 officers assume their new Moreover, I want you to be roles. This issue contains an aware of the dedication and update on Section activities, energy exhibited by the individ- recent CPLR amendments, and uals whom you selected to serve Executive Committee Meeting as officers with me. In addition, summaries. For additional information, including the there are numerous people on the Executive Committee Commercial Division Law Report, please visit the Section who have volunteered and are working hard to make Web site at http://www.nysba.org/sections/comfed. this a great year for our Section. On behalf of the Section, I appreciate your support and This incoming message will have several purposes: welcome your involvement at every level—from read- to recognize certain people, to advise you of new offer- ing the Section’s publications and attending CLE pro- ings by our Section, and to discuss with you certain grams to active committee involvement. -

“The 1961 New York City Zoning Resolution, Privately Owned Public

“The 1961 New York City Zoning Resolution, Privately Owned Public Space and the Question of Spatial Quality - The Pedestrian Through-Block Connections Forming the Sixth-and-a-Half Avenue as Examples of the Concept” University of Helsinki Faculty of Arts Department of Philosophy, History, Culture and Art Studies Art History Master’s thesis Essi Rautiola April 2016 Tiedekunta/Osasto Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos/Institution– Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Filosofian, historian, kulttuurin ja taiteiden tutkimuksen laitos Tekijä/Författare – Author Essi Rautiola Työn nimi / Arbetets titel – Title The 1961 New York City Zoning Resolution, Privately Owned Public Space and the Question of Spatial Quality - The Pedestrian Through-Block Connections Forming the Sixth-and-a-Half Avenue as Examples of the Concept Oppiaine /Läroämne – Subject Taidehistoria Työn laji/Arbetets art – Level Aika/Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä/ Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro gradu Huhtikuu 2016 104 + 9 Tiivistelmä/Referat – Abstract Tutkielma käsittelee New Yorkin kaupungin kaavoituslainsäädännön kerrosneliöbonusjärjestelmää sekä sen synnyttämiä yksityisomisteisia julkisia tiloja ja niiden tilallista laatua nykyisten ihanteiden valossa. Esimerkkitiloina käytetään Manhattanin keskikaupungille kuuden korttelin alueelle sijoittuvaa kymmenen sisä- ja ulkotilan sarjaa. Kerrosneliöbonusjärjestelmä on ollut osa kaupungin kaavoituslainsäädäntöä vuodesta 1961 alkaen ja liittyy olennaisesti New Yorkin kaupungin korkean rakentamisen perinteisiin. Se on mahdollistanut ylimääräisten -

NY Business Law Journal a Publication of the Business Law Section of the New York State Bar Association Inside Headnotes 6 (David L

NYSBA FALL 2008 | VOL. 12 | NO. 2 NY Business Law Journal A publication of the Business Law Section of the New York State Bar Association Inside HeadNotes 6 (David L. Glass) Internet Banking and the Community Reinvestment Act: An Examination of the Proposals to Establish Compliance 8 (Anthony D. Altamuro, Law Student Writing Competition First Place Winner) Auction Rate Securities: Mechanics and Turmoil 16 (Sachin Raval, Law Student Writing Competition Second Place Winner) The Lawyers’ Foreclosure Intervention Network: Addressing Mortgage Foreclosure in New York City 25 (Thomas C. Baxter, Jr. and Michael V. Campbell) Tugboats, Glaucoma and the Check Collection Process 32 (Jay L. Hack) Wrestling the Fire: Climate Change Law in New York State 34 (Nathan Whitehouse) New York Employment Law Update 42 (James R. Grasso) Ethical Issues for Business Lawyers Documents and Lawyers: Oil and Water? 46 (C. Evan Stewart) Intellectual Property in Various Types of Business Transactions 50 (Ralph J. Scola) Preventing the Inevitable: How Thinking About What Might Happen Can Help Ensure That It Won’t 55 (Victoria A. Cundiff) Getting Ready to Sell a Small Business: A Conversation with a Client 71 (Miriam V. Gold) The Role of the Corporate Secretary in Corporate Governance: The View from a U.S. Subsidiary of a Japanese Insurance Company 75 (Yoshikazu Koike) Committee Reports 82 Your key to professional success… A wealth of practical resources at www.nysba.org • Downloadable Forms organized into common The NY Business Law Journal is practice areas also available online • Comprehensive practice management tools • Forums/listserves for Sections and Committees • More than 800 Ethics Opinions • NYSBA Reports – the substantive work of the Association • Legislative information with timely news feeds • Online career services for job seekers and employers • Free access to several case law libraries – exclusively for members Go to www.nysba.org/BusinessLawJournal to access: The practical tools you need. -

Q4 10 Supplemental.Xlsm

Supplemental Operating and Financial Data for the Quarter Ended December 31, 2010 Boston Properties, Inc. Fourth Quarter 2010 Table of Contents Page Company Profile 3 Investor Information 4 Research Coverage 5 Financial Highlights 6 Consolidated Balance Sheets 7 Consolidated Income Statements 8 Funds From Operations 9 Reconciliation to Diluted Funds From Operations 10 Funds Available for Distribution and Interest Coverage Ratios 11 Capital Structure 12 Debt Analysis 13-15 Unconsolidated Joint Ventures 16-17 Value-Added Fund 18 Portfolio Overview-Square Footage 19 In-Service Property Listing 20-22 Top 20 Tenants and Tenant Diversification 23 Office Properties-Lease Expiration Roll Out 24 Office/Technical Properties-Lease Expiration Roll Out 25 Retail Properties - Lease Expiration Roll Out 26 Grand Total - Office, Office/Technical, Industrial and Retail Properties 27 Greater Boston Area Lease Expiration Roll Out 28-29 Washington, D.C. Area Lease Expiration Roll Out 30-31 San Francisco Area Lease Expiration Roll Out 32-33 Midtown Manhattan Area Lease Expiration Roll Out 34-35 Princeton Area Lease Expiration Roll Out 36-37 CBD/Suburban Lease Expiration Roll Out 38-39 Hotel Performance and Occupancy Analysis 40 Same Property Performance 41 Reconciliation to Same Property Performance and Net Income 42-43 Leasing Activity 44 Capital Expenditures, Tenant Improvements and Leasing Commissions 45 Acquisitions/Dispositions 46 Value Creation Pipeline - Construction in Progress 47 Value Creation Pipeline - Land Parcels and Purchase Options 48 Definitions 49-50 This supplemental package contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of the Federal securities laws. You can identify these statements by our use of the words "assumes," "believes," "estimates," "expects," "guidance," "intends," “plans,” “projects,” and similar expressions that do not relate to historical matters. -

Egps Welcomes To

EGPS WELCOMES TO N YC Welcome to New York City! On behalf of the members of the Eastern Group Psychotherapy Society (EGPS), we would like to welcome you to New York City for AGPA Connect 2020. (64th Annual Institute and 77th Annual Conference) of the American Group Psychotherapy Association. New York City has something for everyone from restaurants, museums, theatre, shopping, parks, and historical sites. We hope you take some time during your stay to visit “the city that never sleeps.” Our Hospitality Guide offers you a quick and handy resource with some of EGPS members’ favorite spots. As an island with excellent public transportation, Manhattan offers you easy access to countless activities. We are located centrally in Midtown at the Sheraton Towers, near 5th Avenue's upscale shopping and the Theatre District, Carnegie Hall, Museum of Modern Art and Rockefeller Center. If you head downtown, you can visit SoHo's wonderful art galleries and restaurants. Greenwich Village has delightful coffee shops, restaurants, bookstores, movie theaters and nightclubs. You may enjoy wandering through Tribeca, with its artists' lofts, cobblestone streets, and neighborhood cafés. Little Italy and Chinatown offer shops and markets and restaurants that are definitely worth exploring. You will find all kinds of information on neighborhoods, landmark buildings, sightseeing, entertainment and museums at EGPS’ Hospitality Booth. We are here to provide help and advice from our friendly EGPS members and Hosting Task Force at the booth. We look forward to greeting you and sharing information. Stop by the booth and say hello. Our Hosting Task Force chaired by Kathie Ault, Leah Slivko and assisted by Jan Vadell, our EGPS Administrator and Hosting Task Force Consultant. -

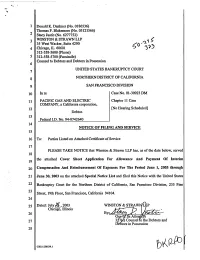

Notice of Filing and Service

1 Donald K. Dankner (No. 0186536) Thomas F. Blakemore (No. 03121566) 2 Stacy Justic (No. 6277752) 3 WINSTON & STRAWN LLP 1! 35 West Wacker, Suite 4200 '50 4 Chicago, IL 60601 1 O3 7-3 312-558-5600 (Phone) 5 312-558-5700 (Facsimile) Counsel to Debtors and Debtors in Possession 6 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT 7 8 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 9 SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION 10 In re Case No. 01-30923 DM 11 PACIFIC GAS AND ELECTRIC Chapter 11 Case COMPANY, a California corporation, 12 [No Hearing Scheduled] Debtor. 13 Federal I.D. No. 94-0742640 - 14 NOTICE OF FILING AND SERVICE 15 16 To: Parties Listed on Attached Certificate of Service 17 PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that Winston & Strawn LLP has, as of the date below, served 18 the attached Cover Sheet Application For Allowance And Payment Of Interim 19 20 Compensation And Reimbursement Of Expenses For The Period June 1, 2003 through 21 June 30, 2003 on the attached Special Notice List and filed this Notice with the United States 22 Bankruptcy Court for the Northern District of California, San Francisco Division, 235 Pine 23 Street, 19th Floor, San Francisco, California 94104. 24 25 Dated: July A, 2003 WINSTON & STRAWLP Chicago, Illinois 26 By 27 3g7Conse TotheDebtors and Motrs n Pssession 28 CHI:1238539.1 bR21 I I Donald K. Dankner (No. 0186536) Thomas F. Blakemore (No. 03121566) 2 Stacy D. Justic (No. 6277752) 3 WINSTON & STRAWN LLP 35 West Wacker Dr. 4 Chicago, IL 60601 Phone: 312-558-5600 5 Facsimile: 312-558-5700 Counsel to Debtor and Debtor in Possession 6 7 8 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT 9 10 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 11 SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION 12 In re Case No. -

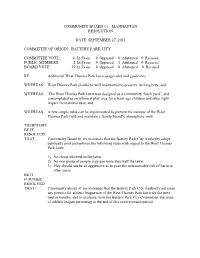

Manhattan Resolution Date: September 27, 2011

COMMUNITY BOARD #1 – MANHATTAN RESOLUTION DATE: SEPTEMBER 27, 2011 COMMITTEE OF ORIGIN: BATTERY PARK CITY COMMITTEE VOTE: 6 In Favor 0 Opposed 0 Abstained 0 Recused PUBLIC MEMBERS: 2 In Favor 0 Opposed 1 Abstained 0 Recused BOARD VOTE: 39 In Favor 0 Opposed 0 Abstained 0 Recused RE: Additional West Thames Park lawn usage rules and guidelines WHEREAS: West Thames Park should be well maintained to preserve its longevity; and WHEREAS: The West Thames Park lawn was designed as a community “back yard”, and contemplated as an informal play area for school-age children and other light- impact recreational uses; and WHEREAS: A few simple rules can be implemented to prevent the overuse of the West Thames Park field and maintain a family friendly atmosphere; now THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED THAT: Community Board #1 recommends that the Battery Park City Authority adopt, publically post and enforce the following rules with regard to the West Thames Park lawn: 1) No cleats allowed on the lawn. 2) No one group of people may use more than half the lawn. 3) Play should not be so aggressive as to pose the unreasonable risk of harm to other users. BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED THAT: Community Board #1 recommends that the Battery Park City Authority not issue any permits for athletic league use of the West Thames Park lawn for the next twelve months, and to evaluate, with the Battery Park City Committee, the issue of athletic league permitting at the end of this twelve month period. COMMUNITY BOARD #1 – MANHATTAN RESOLUTION DATE: SEPTEMBER 27, 2011 COMMITTEE OF ORIGIN: -

NYS Certified MWBE's Contact List

NYS Certified MWBE 's Contact List 3/29/2011 1 Company Name M/WBE LastName First Name Title Phone Email Address City ST Zip Capabilities 781-891-3300 134 West 29th Street New York NY 10001 VoIP and Video Network Assessments, CDR Analysis and Reporting, Advanced Abacus Group, Inc. W Mulloy Mary Pres. 617-489-0200 [email protected] 13 Falmonth Heights Rd. Falmonth MA 02540 ACD Reporting, Voice Recording, Open Source Telephony Consulting 185 Van Rensselaer Blvd. IT staffing, Data storage architecture, design and implementation, Remote online ACube Consulting, Inc M Ahmed Azim Pres. 518-331-3636 [email protected] 2-2B Albany NY 12204 backup/recovery services, Server, desktop, peripheral installation services Medical Archiving Solutions; Media creation and distribution solutions; nComputing solutions for PC consolidation; Data Security solutions; HP Enterprise solutions, servers and storage and HP printers; Emergency Notification consulting services; telecommunications from Alcatel Lucent; consulting services Affinity Enterprises, LLC W Hylant Peg Pres. 518-693-6344 [email protected] 116 East Ave Saratoga Springs NY 12866 for HP platforms and other solution providers. Albany Information Technology Software Development Team Leadership, Custom Software Development from Group, LLC M Woytowich Michael Pres. 518-633-1864 [email protected] 376 Broadway Suite 17 Saratoga Springs NY 12866 requirements through implementation CSCIC Compliance, Risk Assessments, Remediation Plans, Security Policies, information Security Risk Analysis, Reporting & Compliance, IT Project Allen Associates W Allen Mary Beth President 518-482-1431 [email protected] 352 Manning Blvd Albany NY 12206 Management 12047- IT, Business Intelligence, Data Warehousing, Project Management & Business Alternative Insights, Inc. W Smith Susan Pres.