Visual Narratives Portraits of Gerard Reve in His Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Life and Times of the Dutch Blasphemy Law (1932-2014)

The Fall and Rise of Blasphemy Law EDITED BY Paul Cliteur & Tom Herrenberg tt LEIDEN UNIVERSITY PRESS ;. i': .r' ', 4 On the Life and Times of the Dutch Blasphemy Law (1932 -2014) Pctul Cliteur & Tom Herrenberg Cliteur, Paul, and Herrenberg, Tom, " On the Life and Times of the Dutch Blasphemy Law (L993-2014)" , in: The FaII ønd Rise of Press, Leiden 20L6, pp' 71-71'1' TNTRSDUCTT9N Bløsphemy Løw, Leiden University when the Dutch criminal code entered into force in 18B6 it did not contain a general provision against blasphemy. In r88o, during a debate in Parliament about the Criminal Code, the minister of justice at the time, Mr. "God Anthony Ewoud Jan Modderman (1838-1885), opined that is able to preserve His own rights by Himself; no human laws are required for this proposal irrpor".,,'yet, five dãcades later things had changed. A legislative ãf z5 April r93r entitled "Amendment to the Criminal Code with provisions regarding certain utterances hurtful to religious feelings"' sought to add t-o provisions relating to the defamation of religion to the Criminal Code- Article l47 no. r was intended to criminalise "he who verbally, in writing, or in image, publicly exPresses himself by scornful blasphemy in a manner offensive to religious feelingsJ' In addition, Article 4z9bis made it illegal for people to 'displa¡ in a place visible from a public road, words or images that, as e"pressions of scornful blasphemy, are hurtful to religious feelings."3 In this chapter we will give an account of this blasphemy law. We will address the law's evolution in chronological order and start by describing the parliamentary debate on the introduction of the law in the r93os. -

Spring 2019 2 Books from Holland

10 Books from Holland London Book Fair Issue ederlands N letterenfonds dutch foundation for literature Spring 2019 2 Books from Holland Frequently Asked Questions 10 Books from Holland? Who decides the contents? Do you subsidise production costs? Our editors. We want to showcase the best fiction from the This is possible in the case of editions of poetry, illustrated Netherlands for our audience of literary publishers. Most titles children’s books or graphic novels. For regular fiction and have been published recently and have enjoyed good sales, non-fiction, we support translation costs only. excellent reviews and one or more literary awards or nomina- tions. Though sometimes one of these factors is enough. Equally We would like to invite a Dutch author for a promotional visit. important is the question: ‘Does it travel?’ Our advisors talk to If you organise a good programme and offer the author publishers from all over the world and while it is impossible to accommodation, we can cover the travel costs. say with certainty which novels will travel where, we have the expertise to make an educated guess. How to apply for the Amsterdam Fellowship. Every September, we organise a fellowship (4 days) for publish- At book fairs, do you talk about these books exclusively? ers and editors. We do not have an application procedure, but While we like to discuss our catalogue, there are always other you can always send us an e-mail stating your interest. titles: books that have just appeared or are about to come out or books that just missed our selection. -

Literature of the Low Countries

Literature of the Low Countries A Short History of Dutch Literature in the Netherlands and Belgium Reinder P. Meijer bron Reinder P. Meijer, Literature of the Low Countries. A short history of Dutch literature in the Netherlands and Belgium. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague / Boston 1978 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/meij019lite01_01/colofon.htm © 2006 dbnl / erven Reinder P. Meijer ii For Edith Reinder P. Meijer, Literature of the Low Countries vii Preface In any definition of terms, Dutch literature must be taken to mean all literature written in Dutch, thus excluding literature in Frisian, even though Friesland is part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, in the same way as literature in Welsh would be excluded from a history of English literature. Similarly, literature in Afrikaans (South African Dutch) falls outside the scope of this book, as Afrikaans from the moment of its birth out of seventeenth-century Dutch grew up independently and must be regarded as a language in its own right. Dutch literature, then, is the literature written in Dutch as spoken in the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the so-called Flemish part of the Kingdom of Belgium, that is the area north of the linguistic frontier which runs east-west through Belgium passing slightly south of Brussels. For the modern period this definition is clear anough, but for former times it needs some explanation. What do we mean, for example, when we use the term ‘Dutch’ for the medieval period? In the Middle Ages there was no standard Dutch language, and when the term ‘Dutch’ is used in a medieval context it is a kind of collective word indicating a number of different but closely related Frankish dialects. -

Book of War, Mortification and Love J Printed with Blood

Ruud Linssen Book of war, mortification and love j Printed with blood. Read at own risk. Ruud Linssen Book of war, mortification and love About our voluntary suffering ! Underware Den Haag | Helsinki | Amsterdam 2010 Ruud Linssen znxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxnc for Roos Book of war, mortification and love Robin, Rosa About our voluntary suffering Chapter 1: The unmarked letter Chapter 2: Beyond the doctor’s advice Chapter 3: Among lepers Chapter 4: A grove Chapter 5: The meaning of life f Second warning: This book is printed with blood of the author. Continue reading at own risk. 8 Foreword Foreword 9 znxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxnc znxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxnc The history of this book is as perplexing as its content. Since When he delivered the final text, he mentioned that every releasing the typeface Fakir in 2006, we’ve been thinking sentence had been rewritten at least 5 times. Also: ‘this book about an appropriate sampler for this type family. Not being changed my life.’ It gave him a new dimension, as he had never satisfied with our ideas for a Fakir publication at that time, thought about the subject that much. We couldn’t believe we froze the whole publication until an idea would arise that to be true. ‘Yes, it is. Suffering has already been a major theme in which would satisfy us. my life for many years. But not voluntary suffering. This makes a big That happened one year later. In the first year of exist- difference.’ ence of the blackletter Fakir, activities around the typeface The writing of this book became an example of voluntary arose with the theme of voluntary suffering. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/111167 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-10-02 and may be subject to change. `Aan een boom zo volgeladen met Gard Siviki, mist men die ene mispel niet': Gard Sivik versus Podium, 1960-1964. z JEROEN DERA GARD SIVIK EN VIJFTIG Wanneer over het avant-gardetijdschrift Gard Sivik wordt geschreven, gebeurt dat doorgaans tegen de achtergrond van de koerswijziging die het onderging, namelijk die `van een Vlaams experimenteel tijdschrift naar een Nederlands nieuw-realistisch blad.' 2 Het is met name die tweede aandui- ding die in de literatuurgeschiedschrijving domineert. In zijn geschiedenis van de Nederlandse poëzie schrijft Redbad Fokkema bijvoorbeeld: [D]e dichters die in de jaren zestig aan het woord kwamen, boekten (...) succes (...) in Gard Sivik (1955-1964), Barbarber (1958-1971) en in De Nieuwe Stijl (1965-1966). Deze tijdschriften ver-tegenwoordigen in Nederland verschillende vormen van het nieuwe realisme, `ontsprongen uit een treffen met de werkelijkheid', zo schreef Hans Sleutelaar. En dit dan in tegenstelling tot de Vijftigers, die poëzie vooral lieten ontspringen aan een treffen met de taal - overigens zonder de werkelijkheid als inspira- tiebron te ontkennen.3 De door Fokkema gesignaleerde oppositie tussen Vijftigers en nieuw-realis- ten is evident. In de poëtica van de Zestigers 4 - in de redactie van Gard Sivik met name gerepresenteerd door Armando, Sleutelaar, Vaandrager en Ver- hagen - is geen ruimte voor moeilijk gebruik van taal en beeldspraak, maar komt een radicale nuchterheid centraal te staan: `Het "niet-poëtische", het alledaagse en banale wordt steeds belangrijker. -

The Conservative Embrace of Progressive Values Oudenampsen, Merijn

Tilburg University The conservative embrace of progressive values Oudenampsen, Merijn Publication date: 2018 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Oudenampsen, M. (2018). The conservative embrace of progressive values: On the intellectual origins of the swing to the right in Dutch politics. [s.n.]. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. sep. 2021 The conservative embrace of progressive values On the intellectual origins of the swing to the right in Dutch politics The conservative embrace of progressive values On the intellectual origins of the swing to the right in Dutch politics PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan Tilburg University op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. E.H.L. Aarts, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de aula van de Universiteit op vrijdag 12 januari 2018 om 10.00 uur door Merijn Oudenampsen geboren op 1 december 1979 te Amsterdam Promotor: Prof. -

Coetzee, Reve, and the Post-Secular

Coetzee, Reve, and the Post-Secular Research Master‟s Thesis Ted Laros August 15, 2010 Utrecht University, Faculty of Humanities Program: Literary Studies: Literature in the Modern Age Thesis Supervisor: Prof. Paulo de Medeiros Second Reader: Prof. David Pascoe Laros 2 As for grace, no, regrettably no: I am not a Christian, or not yet. —J. M. Coetzee to David Attwell in Doubling the Point BEKENTENIS Voordat ik in de Nacht ga die voor eeuwig lichtloos gloeit, wil ik nog eenmaal spreken, en dit zeggen: dat ik nooit anders heb gezocht dan U, dan U, dan U alleen. —Gerard Reve, Nader tot U Laros 3 Contents Acknowledgments 4 1. Introduction: Literature and the Post-Secular 5 2. “Post-Secular Fiction”: The Post-Secular Hermeneutics of John A. McClure 14 2.1. Characteristics of Post-Secular Fiction 15 2.2. The Practical Projects that Post-Secular Fiction Converses with 19 2.3. The Theoretical Projects that Post-Secular Fiction Converses with 24 2.3.1. The Logic of (Partial) Belief 25 2.3.2. “Weak Religion” 27 2.3.3. “Crasser Supernaturalism” 33 2.3.4. “Preterite Spiritual” Communalism/“Neo-Monastic” Politics 35 2.4. Conclusion 41 3. Coetzee and the Post-Secular 43 3.1. A Change of Heart 44 3.2. Between the Real and the Anti-Real 59 3.3. “Ora et labora”/“A Project of Love” 66 3.4. Conclusion 73 4. Reve and the Post-Secular 76 4.1. A Profoundly Weakened Religiosity 81 4.2. “De dag is vol tekenen” 99 4.3. A Homosexual Covenant 102 4.4. -

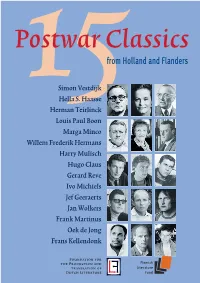

From Holland and Flanders

Postwar Classics from Holland and Flanders Simon Vestdijk 15Hella S. Haasse Herman Teirlinck Louis Paul Boon Marga Minco Willem Frederik Hermans Harry Mulisch Hugo Claus Gerard Reve Ivo Michiels Jef Geeraerts Jan Wolkers Frank Martinus Oek de Jong Frans Kellendonk Foundation for the Production and Translation of Dutch Literature 2 Tragedy of errors Simon Vestdijk Ivory Watchmen n Ivory Watchmen Simon Vestdijk chronicles the down- I2fall of a gifted secondary school student called Philip Corvage. The boy6–6who lives with an uncle who bullies and humiliates him6–6is popular among his teachers and fellow photo Collection Letterkundig Museum students, writes poems which show true promise, and delights in delivering fantastic monologues sprinkled with Simon Vestdijk (1898-1971) is regarded as one of the greatest Latin quotations. Dutch writers of the twentieth century. He attended But this ill-starred prodigy has a defect: the inside of his medical school but in 1932 he gave up medicine in favour of mouth is a disaster area, consisting of stumps of teeth and literature, going on to produce no fewer than 52 novels, as the jagged remains of molars, separated by gaps. In the end, well as poetry, essays on music and literature, and several this leads to the boy’s downfall, which is recounted almost works on philosophy. He is remembered mainly for his casually. It starts with a new teacher’s reference to a ‘mouth psychological, autobiographical and historical novels, a full of tombstones’ and ends with his drowning when the number of which6–6Terug tot Ina Damman (‘Back to Ina jealous husband of his uncle’s housekeeper pushes him into Damman’, 1934), De koperen tuin (The Garden where the a canal. -

The Meaning of a Kiss Different Historiographical Approaches to the Sixties in the Netherlands

412-20361_04 02.11.2009 14:48 Uhr Seite 51 L’Homme. Z. F. G. 20, 2 (2009) The Meaning of a Kiss Different Historiographical Approaches to the Sixties in the Netherlands Mineke Bosch A Famous Kiss On August 26, 1969 at the historical site of the castle Muiderslot, a memorable kiss was exchanged between the ‘romantic decadent’ writer Gerard Reve (1923) and the Catholic Minister of Culture, Leisure and Social Work, Marga Klompé (1912).1 It hap- pened at the occasion of the presentation of the “P. C. Hooft Prize”, the most impor- tant and at the time still a state prize for literature. Both of the involved persons were pioneers in their own fields. He, Gerard Reve, was a publicly gay writer who in 1947 had made his entry in the world of literature with a prize winning book “De Avonden” (The Evenings) in which he gave an merciless picture of lower middle class life. In the early Fifties he had been denied a travel grant by the Catholic Minister of Culture Joseph Cals for his trespassing the boundaries of ‘public morality’ in his work: he had hinted at masturbation in his short story “Melancholia”. In 1966 – one year after Reve had converted to Catholicism – he was prosecuted for blasphemy resulting from the accusation of a member of the Ortho- dox Protestant Party. Reve had imagined God coming to his door in the shape of a small grey donkey which he would then lead to his small room in the attic to tenderly take possession of Him. In 1968 he was cleared of the charge and what is more: he came out a ‘better person’, as his own defence at the trial which emphasised the importance of free speech was widely appreciated.2 1 For a quick introduction see J. -

![The Fourth Man] Peter Verstraten, University of Leiden](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4627/the-fourth-man-peter-verstraten-university-of-leiden-3674627.webp)

The Fourth Man] Peter Verstraten, University of Leiden

The Irony of Irony: On Paul Verhoeven’s Adaptation of Gerard Reve’s De vierde man [The Fourth Man] Peter Verstraten, University of Leiden Abstract: Since the literary increasingly tends to refer to a mode ‘between page and screen’, the so-called adaptation studies are ‘on the move’ again. This article examines the not very recent, but nonetheless too sporadically examined case of ‘Dutch novel into Dutch film’ in order to consider whether there might be some leeway for film to position itself as a viable subject within Dutch studies. Against this background, a film inspired by a book by the renowned post-war writer Gerard Reve is analysed to argue that adaptation studies have the advantage of urging us to address the ‘form/content dilemma’: formal adjustments are required in case content is transferred from one medium to another. Paul Verhoeven’s 1983 adaptation of De vierde man [The Fourth Man] shows that the only way for film makers to work in the spirit of Reve is to insist on ‘the necessity of infidelity to its letter or form’. Opting for a ‘functional likeness’ rather than imitation, Verhoeven privileges the cinematic devices of deep focus and hyper-real colours in order to achieve the effect of an ‘irony of the irony’. Keywords: Irony, Adaptation, Dutch Cinema, Gothic, Femme Céleste If the approach of (Anglo-Saxon) literary studies has been predominantly ‘aesthetic’, Thomas Leitch asserts in his Film Adaptations & Its Discontents, then the approach of cinema studies can be called ‘analytical’.1 When film entered academia as an object of study in the ideologically charged decades of the 1960s and 1970s, scholars were above all interested in ‘mining film after film for political critique’.2 Since adaptation critics, by contrast, were basically preoccupied with aesthetic concerns, they felt more at home within literary studies which had a tradition of regarding artistic value criteria as a touchstone. -

The Aggressive Logic of Singularity: Willem Frederik Hermans1 Frans Ruiter, University of Utrecht, and Wilbert Smulders, University of Utrecht

The Aggressive Logic of Singularity: Willem Frederik Hermans1 Frans Ruiter, University of Utrecht, and Wilbert Smulders, University of Utrecht Abstract: Willem Frederik Hermans is considered to be one of the major Dutch authors of the twentieth century. In his novels ideals of every kind are unmasked, and his Weltanschauung leaves little room for pursuing a ‘good life’. Nevertheless, there seems to be one option left to him, namely literature. In his poetic essays he explains that literature has nothing to do with escapism, but offers a vital way of facing the bleak facts of life. Literary critics and scholars have commented extensively on his poetic ideas, but have never truly addressed the riddle Hermans’ œuvre confronts us with: what might be the value of writing in a world without values? In this article we will focus on this paradoxical problem, which could perhaps be characterized as one of ‘aesthetics of nihilism’. We argue that Hermans’ so-called autonomous and a-political literary position can certainly be interpreted as a form of commitment that goes far beyond literature. We will first give an overview of Hermans’ work. Subsequently we will reflect on the social and cultural status of literary autonomy. Our main aim is to analyze a critical text by Hermans which seems clear at first sight but actually is rather enigmatic: the compact, well- known essay Antipathieke romanpersonages (‘Unsympathetic Fictional Characters’).2 Keywords: Literary Autonomy, Alterity, Willem Frederik Hermans Singularity: to Spring a Leak in the Fullness… In his autobiographical story Het grote medelijden (The Great Compassion) Hermans’ alter ego Richard Simmilion says about the people who surround him, i.e. -

De Interviewer En De Schrijvers Ischa Meijer Samenstelling

De interviewer en de schrijvers Ischa Meijer Samenstelling Connie Palmen bron Ischa Meijer, De interviewer en de schrijvers (samenstelling Connie Palmen). Prometheus, Amsterdam 2003 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/meij012inte04_01/colofon.htm © 2007 dbnl / erven Ischa Meijer 7 Jan Wolkers Jan Wolkers liet zijn - praktisch voltooide - roman De walgvogel, waarvan de reeds ontworpen cover de wand siert, in de steek, om, geïnspireerd door de gebeurtenissen van de Veertiende Juni, subtiel te beginnen aan De hittegolf. Wolkers: ‘Nee, het is geen beschrijving van de situatie van die dag. Het is een roman. Ik was erbij. Ik stond bij de bouwvakkers. Uit de gebeurtenissen van die dag ontstond de gedachte voor een roman. Nee, ik vertel u er niets van. Dat is m'n gewoonte niet.’ Als u terugdenkt aan die dag... Wat zijn de dingen die u het meest gefrappeerd hebben? ‘Dat zeg ik niet...’ Kunt u iets zeggen over de intrige? ‘Nee, dat is heel moeilijk. Voordat het kind geboren is, kan je d'r niks over zeggen, hè. Pas als het nageltjes en teentjes heeft... Ik laat m'n manuscripten nooit lezen voor ze af zijn. Nooit. Er is een enorm verschil tussen het boek van Mulisch over de provo's en het gedonder in Amsterdam. Mijn boek is een roman.’ We drinken koffie. De werkruimte van Wolkers is in tweeën gedeeld. Een grote ruimte waar hij overdag aan het beeldhouwen is, een trapje naar boven voert naar het tweede plan: een zitje en de tafel waaraan hij 's avonds schrijft. Direct op de tikmachine. Wolkers: ‘Ik bewaar al m'n manuscripten.