Benedict Wharf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Merton Council

Committee: CABINET Date: 21st September 2009 Agenda item: 6 Wards: All Wards Subject: S.106 Planning Obligations Report Quarter 1 2009/10 Lead officer: John Hill, Head of Public Protection & Development Lead member: Councillor William Brierly, Planning and Traffic Management Forward Plan reference number: 825 Contact officer: Tim Catley (S.106 General Enquiries); Ashley Heller (Enquires in relation to the Wimbledon Station Access Scheme) Recommendations: A. THE CONTRIBUTIONS MADE BY S.106 AGREEMENTS OR ANY OTHER ENABLING AGREEMENT BE NOTED. B. THAT S.106 FUNDING TOTALING £248,310 BE ALLOCATED TO THE WIMBLEDON STATION ACCESS SCHEME 1 PURPOSE OF REPORT AND EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1. This report summarises the situation in relation to S.106 agreements for the 1st quarter 2009/10. 1.2. £511,107 has been committed to the council in monetary obligations for Quarter 1. A list of agreements signed during Quarter 1 can be found at Appendix B. 1.3. £65,722 was received in Quarter 1. A breakdown can be found at item 2.6. 1.4. £45,299 was spent from S.106 funds in Quarter 1. Please refer to Appendix C for breakdown. 1.5. £1,595,735 is unallocated and remains available from S.106 income. Please refer to Appendix D. 1.6. To approve the proposed use of S.106 funds towards the Wimbledon Station Access Scheme. 2 DETAILS 2.1. S.106 of the Town & Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended) permits Local Planning Authorities to enter into agreements with applicants for planning permission to regulate the use and development of land. -

Benedict Wharf Report

representation hearing report GLA/4756/03 8 December 2020 Land at Benedict Wharf, Mitcham in the London Borough of Merton planning application no. 19/P2383 Planning application Town & Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended); Greater London Authority Acts 1999 and 2007; Town & Country Planning (Mayor of London) Order 2008 (“the Order”). The proposal Outline planning application (with all matters reserved) for the redevelopment of the site comprising the demolition of existing buildings and development of up to 850 new residential dwellings (Class C3 use) and up to 750 sq.m. of flexible commercial floorspace (Class A1-A3, D1 and D2 use), together with associated car parking, cycle parking, landscaping and infrastructure. The applicant The applicant is SUEZ Recycling and Recovery Ltd and the architect is PRP Recommendation summary The Deputy Mayor for Planning, Regeneration and Skills (acting under delegated powers),acting as the Local Planning Authority for the purpose of determining this application; i. grants conditional outline planning permission in respect of application 19/P2383 for the reasons set out in the reasons for approval section below, and subject to the prior completion of a Section 106 legal agreement; ii. delegates authority to the Head of Development Management to: a) agree the final wording of the conditions and informatives as approved by the Deputy Mayor; with any material changes being referred back to the Deputy Mayor; b) agree any variations to the proposed heads of terms for the Section 106 legal agreement and negotiate, agree the final wording, and sign and execute and complete the Section 106 legal agreement; and c) issue the outline planning permission; and page 1 d) to refer the application back to the Deputy Mayor in order to refuse planning permission if by, 8 April 2021, the Section 106 legal agreement has not been completed; iii. -

Sustainability Scoping Report

Sustainability Appraisal (SA)/Strategic Environment Assessment (SEA) Scoping Report Merton Council Estates Plan September 2014 Contacts and further information Further information on the SA/SEA of the Estates Local Plan on Merton’s website: Insert link here or: London Borough of Merton Future Merton,12TH Floor Civic Centre London Road SM4 5DX [email protected] Telephone : 020 8545 3693 1 1 Introduction 1.1 This Scoping Report is the first stage of a Sustainability Appraisal (SA), which incorporates the requirements for a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) for the Estates Plan (herein referred to as ‘the Plan’), part of Merton’s Local Plan. 2 Purpose of Sustainability Appraisal and Strategic Environment Assessment (SEA) 2.1 The EU Strategic Environmental Assessment Directive 2001/42/EC (SEA Directive), implemented in the UK by the SEA Regulations 2004, requires environmental assessment to be undertaken on all plans and programmes where they are likely to have significant environmental impacts. 2.2 The purpose of Sustainability Appraisal (incorporating SEA) is to promote sustainable development by integrating social, economic, and environmental considerations into the preparation of new or revised plans and strategies. It is imperative to commence SEA at the early stages of plan making to identify the key sustainability issues likely affected by the implementation of the plan; it assists with creating development options and assesses any significant effects of the proposed development. SA/SEA’s are an important tool for developing sound planning policies and planning development plans which are consistent with the Government’s sustainable development agenda and achieving the aspirations of local communities. -

HSL Report Template. Issue 1. Date 04/04/2002

Harpur Hill, Buxton, SK17 9JN Telephone: 01298 218000 Facsimile: 01298 218590 E Mail: [email protected] A survey of UK tram and light railway systems relating to the wheel/rail interface FE/04/14 Project Leader: E J Hollis Author(s): E J Hollis PhD CEng MIMechE Science Group: Engineering Control DISTRIBUTION HSE/HMRI: Dr D Hoddinott Customer Project Officer/HM Railway Inspectorate Mr E Gilmurray HIDS12F Research Management LIS (9) HSL: Dr N West HSL Operations Director Dr M Stewart Head of Field Engineering Section Author PRIVACY MARKING: D Available to the public HSL report approval: Dr M Stewart Date of issue: 14 March 2006 Job number: JR 32107 Registry file: FE/05/2003/21511 (Box 433) Electronic filename: Report FE-04-14.doc © Crown Copyright (2006) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To the people listed below, and their colleagues, I would like to express my thanks for all for the help given: Blackpool Borough Council Brian Vaughan Blackpool Transport Ltd Bill Gibson Croydon Tramlink Jim Snowdon Dockland Light Railway Keith Norgrove Manchester Metrolink Steve Dale Tony Dale Mark Howard Mark Terry (now with Rail Division of Mott Macdonald) Midland Metro Des Coulson Paul Morgan Fred Roberts Andy Steel (retired) National Tram Museum David Baker Geoffrey Claydon Mike Crabtree Allan Smith Nottingham Express Transit Clive Pennington South Yorkshire Supertram Ian Milne Paul Seddon Steve Willis Tyne & Wear Metro (Nexus) Jim Davidson Peter Johnson David Walker Parsons Brinkerhoff/Permanent Way Institution Joe Brown iii Manchester Metropolitan University Simon Iwnicki Julian Snow Paul Allen Transdev Edinburgh Tram Andy Wood HM Railway Inspectorate Dudley Hoddinott Dave Keay Ian Raxton iv CONTENTS 1 Introduction............................................................................................................. -

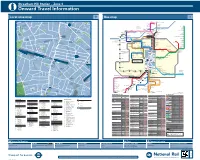

Streatham Hill Station – Zone 3 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

Streatham Hill Station – Zone 3 i Onward Travel Information Local area map Bus map R U S H C O M M O N M E W S 35 3 73 2 43 T T E Y N B U A 126 R Orchard E W U The White House School Y C I C H O U L L P St. Pancras 1 A R T Primary H 133 2 and Woodentops 20 C 11 O E P Kindergarten Sinclair Crown & Sceptre School Christ Church C of E CHALLICE WAY E International Liverpool Street U R R Primary School 120 92 T 59 N C U Estate N Hayes Court H R L S King’s D I T E F S H E Euston O R A T U H T Y G I Cross Old Broad Street R L G O C O O A I N L V S S D L R H P E W D L G A 27 G C A A L A E A U E N R Y 58 5 Christ Church O D O C A R E E N I R I E R D R S L N L L S E C of E Church L L Russell Square St. Bede’s N O A 259 R C E L R L H H E Bank FORTROSE L 59 C P C S I E 106 RC Church GA A H U 22 D T R O RD N O R R P13 E T E R 96 G O A S NS 1 N 7 A K A N 104 M D C St. -

Minutes Document for Mitcham Community Forum, 27/02/2020 19:15

MITCHAM COMMUNITY FORUM 27 FEBRUARY 2020 (7.15 pm - 9.00 pm) PRESENT Councillors (in the Chair), Councillor David Chung 1 WELCOME AND INTRODUCTIONS (Agenda Item 1) The meeting was held at Vestry Hall, and chaired by Councillor David Chung. Around 20 residents attended, as well as three other Councillors, and officers of the council and its partners. The Chair welcomed everyone to the meeting. 2 LONDON ASSEMBLY UPDATE (Agenda Item 2) Leonie Cooper, Assembly Member for Merton and Wandsworth, provided any update on the work of the London Assembly. The role of Assembly is primarily to hold the Mayor of London to account. There are 25 Assembly Members, 14 geographical, 11 from a top-up list. At the moment five parties are represented Labour, Conservative, Liberal Democrat, UKIP and Green parties. There are a series of cross party committees. Leonie is currently Deputy Chair of the Environment Committee, and Chair of Economy Committee. The committees look at range of projects for example single use plastics, which resulted in roll out of water fountains; biodiversity and housing, which has been integrated into new London Plan. The Economy Committee looked at high streets, which included evidence from Love Wimbledon The final version of the London Plan is currently with the Secretary of State for approval. The plan includes requirements for net-biodiversity improvement on developments and for urban green space. Currently the Mayors proposed budget is under scrutiny. The Mayor has a budget of £18bn covering Transport for London; the Metropolitan Police; London Fire Brigade; a number of develop corporations; and specific projects like the night-time economy, and London is Open. -

(By Email) Our Ref: MGLA111220-1801 14 January 2021 Dear Thank You for Your Request for Information Which the GLA Received on D1

(By email) Our Ref: MGLA111220-1801 14 January 2021 Dear Thank you for your request for information which the GLA received on D11 December 2020. Your request has been dealt with under the Environmental Information Regulations (EIR) 2004. You asked for: Please provide copies of all the representations received in relation to the Representation Hearing on 8 December 2020 into the development of Benedict Wharf, Mitcham (GLA reference GLA/4756) and a link to where these may be accessed publicly online Our response to your request is as follows: Please find attached the information the GLA holds within scope of your request. Please note that some names and contact details are exempt from disclosure under Regulation 13 (Personal information) of the EIR. Information that identifies specific employees constitutes as personal data which is defined by Article 4(1) of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) to mean any information relating to an identified or identifiable living individual. It is considered that disclosure of this information would contravene the first data protection principle under Article 5(1) of GDPR which states that Personal data must be processed lawfully, fairly and in a transparent manner in relation to the data subject If you have any further questions relating to this matter, please contact me, quoting the reference at the top of this letter. Yours sincerely Information Governance Officer If you are unhappy with the way the GLA has handled your request, you may complain using the GLA’s FOI complaints and internal -

4756 Stage 1 Decision Letter and Report, Item 2. PDF 268 KB

Minute Item 2 Page 1 Page 2 planning report GLA/4756/01 30 September 2019 Land at Benedict Wharf, Mitcham in the London Borough of Merton planning application no: 19/P2383 Strategic planning application stage 1 referral Town & Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended); Greater London Authority Acts 1999 and 2007; Town & Country Planning (Mayor of London) Order 2008. The proposal Outline planning permission (with all matters reserved) for the residential-led mixed use redevelopment of the site to construct up to 600 residential units and 500 sq.m. of flexible commercial/community floorspace in Class A1-A3, D1 and D2 use). The applicant The applicant is SUEZ Recycling and Recovery UK Ltd and the architect is PRP Architects Strategic issues Land use principle: Compensatory re-provision of waste management capacity would be provided; however, further discussion and the written agreement of the South London Waste Plan boroughs is required to confirm that the loss of Benedict Wharf would not compromise the potential to meet the apportionment and self- sufficiency targets in the draft London Plan. Residential-led development of this designated SIL site does not accord with the London Plan or draft London Plan. Further viability and marketing evidence is required to demonstrate the applicant’s case for exceptional circumstances in this particular instance (paragraphs 17 to 44). Housing and affordable housing: 20% affordable housing offer, comprising a 60:40 tenure split between London Affordable Rent and London Shared Ownership is wholly unacceptable. This must be significantly improved by fully exploring the potential for grant funding and greater optimisation of the proposed residential density. -

118 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

118 bus time schedule & line map 118 Morden - Brixton View In Website Mode The 118 bus line (Morden - Brixton) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Brixton: 24 hours (2) Morden: 12:05 AM - 11:45 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 118 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 118 bus arriving. Direction: Brixton 118 bus Time Schedule 41 stops Brixton Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 24 hours Monday 24 hours Morden Station (C) 59 London Road, London Tuesday 24 hours Morden Hall (E) Wednesday 24 hours 14 Morden Hall Road, London Thursday 24 hours Morden Hall Road / Central Road (P) Friday 24 hours 108 Morden Hall Road, London Saturday 24 hours Morden Hall Park / Surrey Arms (Q) Belgrave Walk Tram Stop (M) Mitcham Tram Stop (T) 118 bus Info Direction: Brixton Gedge Court (S) Stops: 41 Trip Duration: 49 min Mitcham / Cricket Green (P) Line Summary: Morden Station (C), Morden Hall (E), Broadway Gardens, London Morden Hall Road / Central Road (P), Morden Hall Park / Surrey Arms (Q), Belgrave Walk Tram Stop Mitcham / Lower Green (L) (M), Mitcham Tram Stop (T), Gedge Court (S), Mitcham / Cricket Green (P), Mitcham / Lower Green Glebe Court (J) (L), Glebe Court (J), Upper Green East (H), Three Kings Pond (T), Cedars Avenue (E), Tamworth Park Upper Green East (H) (E), Sherwood Park Road (N), Robinhood Lane (S), Northborough Road (P), Stanford Way (VA), 41 Upper Green East, London Longthornton Road (VE), Rowan Crescent (VF), Three Kings Pond (T) Greyhound Terrace (VH), Braeside Road (VJ), Streatham -

Route Option 2 – Colliers Wood to Sutton Town Centre a Street-Based Route from Colliers Wood to Sutton Town Centre Via Rosehill

What is the Sutton Link project? Figure 1: Route Option 2 – Colliers Wood to Sutton We are consulting on proposals for a new, direct and town centre quicker transport link between Sutton and Merton. We have called this the Sutton Link. The Sutton Link would create a high-capacity route for people travelling between Sutton town centre and Merton using zero-emission vehicles. It would connect with other major transport services into central London and across south London, including National Rail, London Underground, existing tram and bus services. It would make journeys by public transport quicker and more attractive, and reduce the need for trips by private car. Many of the neighbourhoods along the proposed routes have limited public transport options. The Sutton Link would support new homes being built and would improve access to jobs, services, major transport hubs and leisure opportunities across both boroughs and beyond. We are considering a tram or ‘bus rapid transit’ (BRT) for the Sutton Link. Route Option 2 – Colliers Wood to Sutton town centre A street-based route from Colliers Wood to Sutton town centre via Rosehill. It would, interchange with the existing London Trams network at Belgrave Walk tram stop and the Northern line at Colliers Wood. A tram or BRT service would be suitable for this route. Main works required for Route Option 2 The route mostly operates along existing streets and • Approximately 9km of tram or BRT corridor the majority of works would therefore take place between Colliers Wood and Sutton, including a within -

Policy N3.2 Mitcham

Policy N3.2 Mitcham Mitcham neighbourhood © Crown copyright [and database rights] (2018) OS (London Borough of Merton 100019259. 2018) Policy N3.2 Mitcham Town Centre To improve the overall environment of Mitcham town centre by providing quality shopfronts, new homes, good transport links. We will do this by: a. Increasing the footfall and spend in the town centre, improving the quality of shops and services; b. Creating healthier streets, continuing to enhance the public realm through high quality streetscape and urban design improvements to shop fronts and public spaces. c. Make Mitcham town centre easier to walk around and easier to get to by walking, cycling and public transport, requiring new developments and new public realm investment to help create an easier, more legible, coherent, layout of streets and spaces, removing barriers. d. Improving the quality and mix of all tenures, in particular supporting homes above shops in the town centre; e. Supporting businesses, leisure, community and retail outlets that are attractive to and used by the whole community. f. Supporting businesses and enterprise; Surrounding area of Mitcham Town Centre To improve the overall environment of Mitcham surrounding areas by providing quality shopping, housing, community facilities and good transport links. The council will do this by: g. Supporting North Mitcham Local Centre: only supporting development that complements or improves the local or wider public realm; h. Improving the quality and mix of homes including affordable and private housing; i. Ensuring that development conserves and enhances the historic environment, for example, around Cricket Green, Canons House and Mitcham Common; j. Enhancing the public realm through high quality urban design and architecture, and permitting development that makes a positive visual impact to the overall surroundings and connectivity to the town centre; k. -

Sutton Link Consultation Report

Sutton Link Consultation Report April 2019 Contents Executive summary ..................................................................................................... 4 1. About the proposals ............................................................................................ 5 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Purpose .......................................................................................................... 7 2. About the consultation ...................................................................................... 10 2.1 Purpose ........................................................................................................ 10 2.2 Consultation history ...................................................................................... 10 2.3 TfL’s consultation - Who we consulted ......................................................... 10 2.4 Dates and duration ....................................................................................... 10 2.5 What we asked ............................................................................................. 11 2.6 Methods of responding ................................................................................. 11 2.7 Consultation materials and publicity ............................................................. 11 2.8 Equalities Assessment ................................................................................. 14 2.9 Analysis of consultation