Alaris Capture Pro Software

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

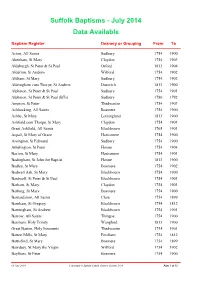

Baptism Data Available

Suffolk Baptisms - July 2014 Data Available Baptism Register Deanery or Grouping From To Acton, All Saints Sudbury 1754 1900 Akenham, St Mary Claydon 1754 1903 Aldeburgh, St Peter & St Paul Orford 1813 1904 Alderton, St Andrew Wilford 1754 1902 Aldham, St Mary Sudbury 1754 1902 Aldringham cum Thorpe, St Andrew Dunwich 1813 1900 Alpheton, St Peter & St Paul Sudbury 1754 1901 Alpheton, St Peter & St Paul (BTs) Sudbury 1780 1792 Ampton, St Peter Thedwastre 1754 1903 Ashbocking, All Saints Bosmere 1754 1900 Ashby, St Mary Lothingland 1813 1900 Ashfield cum Thorpe, St Mary Claydon 1754 1901 Great Ashfield, All Saints Blackbourn 1765 1901 Aspall, St Mary of Grace Hartismere 1754 1900 Assington, St Edmund Sudbury 1754 1900 Athelington, St Peter Hoxne 1754 1904 Bacton, St Mary Hartismere 1754 1901 Badingham, St John the Baptist Hoxne 1813 1900 Badley, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1902 Badwell Ash, St Mary Blackbourn 1754 1900 Bardwell, St Peter & St Paul Blackbourn 1754 1901 Barham, St Mary Claydon 1754 1901 Barking, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1900 Barnardiston, All Saints Clare 1754 1899 Barnham, St Gregory Blackbourn 1754 1812 Barningham, St Andrew Blackbourn 1754 1901 Barrow, All Saints Thingoe 1754 1900 Barsham, Holy Trinity Wangford 1813 1900 Great Barton, Holy Innocents Thedwastre 1754 1901 Barton Mills, St Mary Fordham 1754 1812 Battisford, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1899 Bawdsey, St Mary the Virgin Wilford 1754 1902 Baylham, St Peter Bosmere 1754 1900 09 July 2014 Copyright © Suffolk Family History Society 2014 Page 1 of 12 Baptism Register Deanery or Grouping -

Of the National Trust Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SECRET GARDENS : OF THE NATIONAL TRUST PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Claire Masset | 192 pages | 01 Jun 2017 | PAVILION BOOKS | 9781909881907 | English | London, United Kingdom Secret Gardens : of the National Trust PDF Book Rockside Hydro-Matlock. Out on the estate there are woods and fields to explore with places to build a den and a flooded meadow to spot migrating birds. Luli Novelty Set of 6. It also has some exclusive spas and restaurants. All Rights Reserved. Forgotten password Please enter your email address below and we'll send you a link to reset your password. Bodnant Garden, Conwy. Nestling in the Southern Peak District, three high quality barns, beautifully…. Lucy Foley. National Trust. The gardens were laid out by the 2nd Lord Aberconway in and were presented to the National Trust in Stunning photographs of the Trust's idiosyncratic gardens are accompanied by a light text meditating on the magic of the secret garden, and bringing in fascinating historical and botanical details. A whimsical and beautiful book celebrating these hidden gems of the National Trust — from specially made secret gardens to overlooked corners of famous gardens and re-discovered lost gardens. All Rights Reserved. The Secret Garden. Shuggie Bain. This book contains details of gardens which open for the scheme throughout England and Wales. Late 18th - century orangery , on border of Jonathan McManus Getty Images. Sunny relaxing location with great walking from front door. Further south the land is abundant with deep valleys and vast forests. Have your own secret garden adventure when you visit. Call us on or send us an email at. -

Excursions 1997. Report and Notes on Some Findings. 19

EXCURSIONS1997 Reportand noteson somefindings 19 April. Philip Aitkens Ixworth, Garboldishamand North Lopham The towers of these three churches are believed to have been built by the 15th-century workshopof master masons,Aldrichof North Lopham, Norfolk. Acontract wasdrawn up in 1486between the churchwardens of Helmingham and Thomas Aldrich of North Lopham to construct their tower; today, it has a fine inscription at the base. North Lopham tower is believed,from evidencein wills,to have been commencedin 1479;an inscriptionby the same hand as that at Helminghamappears at mid-heighton the north side,but at the base isa band ofstone devices,flushwork-filled.Inscriptionsdated c.1480-1500are alsofound, for example, at Brockley(on the tower),Botesdale(over the north door) and Garboldisham(north porch), all by the same hand. Similardevicesin flushworkare to be found on many other churches c. 1460-80,especiallyat the basesof towers:those at Ixworth, BadwellAshand Elmswellform a notable group. SeealsoGarboldisham,Northwold,Fincham,NewBuckenham,Kenninghall and Mendlesharn. Other architectural features closelymatch, clear evidence of a common designer. These are mostlydatable by willsto c.1460-80. It is believedthat a new generation at the Aldrich workshop commences c. 1486, favouring inscriptions instead of flushwork devices. Acontract wasmade withThomas Aldrichto rebuild the east wallofThetford Priory, 1505-07. lxworth, St Mary'sChurch. The annual general meeting washeld here by kind permissionof the Revd P. Oliver. The tower was begun c. 1472, as evidenced by the 'Thomas Vyal' tile, commemorating the bequest of six marks by a prosperous localcarpenter in Decemberthat year,for workon the new`stepyr,and twotilesinscribedwiththe name ofWilliamDensy,Prior of the Augustinianhouse at Ixworth, 1467-84,one of them alsodated 1472. -

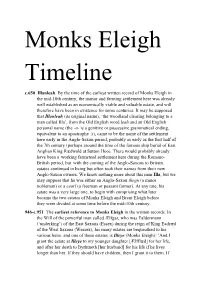

C.650 Illanleah. by the Time of the Earliest Written Record of Monks

Monks Eleigh Timeline c.650 Illanleah. By the time of the earliest written record of Monks Eleigh in the mid-10th century, the manor and farming settlement here was already well established as an economically viable and valuable estate, and will therefore have been in existence for some centuries. It may be supposed that Illanleah (its original name), ‘the woodland clearing belonging to a man called Illa’, from the Old English word leah and an Old English personal name (the -n- is a genitive or possessive grammatical ending, equivalent to an apostrophe ‘s), came to be the name of the settlement here early in the Anglo-Saxon period, probably as early as the first half of the 7th century (perhaps around the time of the famous ship burial of East Anglian King Rædwald at Sutton Hoo). There would probably already have been a working farmstead settlement here during the Romano- British period, but with the coming of the Anglo-Saxons to Britain, estates continued in being but often took their names from their new Anglo-Saxon owners. We know nothing more about this man Illa, but we may suppose that he was either an Anglo-Saxon thegn (a minor nobleman) or a ceorl (a freeman or peasant farmer). At any rate, his estate was a very large one, to begin with comprising what later became the two estates of Monks Eleigh and Brent Eleigh before they were divided at some time before the mid-10th century. 946-c.951 The earliest reference to Monks Eleigh in the written records. In the Will of the powerful man called Ælfgar, who was Ealdormann (‘underking’) of the East Saxons (Essex) during the reign of King Eadræd of the West Saxons (Wessex), his many estates are bequeathed to his various heirs, and one of these estates is Illeye (Monks Eleigh): ‘And I grant the estate at Illeye to my younger daughter [Ælfflæd] for her life, and after her death to Byrhtnoth [her husband] for his life if he lives longer than her. -

Babergh District Council

Draft recommendations on the new electoral arrangements for Babergh District Council Consultation response from Babergh District Council Babergh District Council (BDC) considered the Local Government Boundary Commission for England’s draft proposals for the warding arrangements in the Babergh District at its meeting on 21 November 2017, and made the following comments and observations: South Eastern Parishes Brantham & Holbrook – It was suggested that Stutton & Holbrook should be joined to form a single member ward and that Brantham & Tattingstone form a second single member ward. This would result in electorates of 2104 and 2661 respectively. It is acknowledged the Brantham & Tattingstone pairing is slightly over the 10% variation threshold from the average electorate however this proposal represents better community linkages. Capel St Mary and East Bergholt – There was general support for single member wards for these areas. Chelmondiston – The Council was keen to ensure that the Boundary Commission uses the correct spelling of Chelmondiston (not Chelmondistan) in its future publications. There were comments from some Councillors that Bentley did not share common links with the other areas included in the proposed Chelmondiston Ward, however there did not appear to be an obvious alternative grouping for Bentley without significant alteration to the scheme for the whole of the South Eastern parishes. Copdock & Washbrook - It would be more appropriate for Great and Little Wenham to either be in a ward with Capel St Mary with which the villages share a vicar and the people go to for shops and doctors etc. Or alternatively with Raydon, Holton St Mary and the other villages in that ward as they border Raydon airfield and share issues concerning Notley Enterprise Park. -

FALL 2019 2 | from the Executive Director

Americans in Alliance with the National Trust of England, Wales, and Northern Ireland The Horse and the Country House The Lost House Revisited Restoring Britain’s Waterways FALL 2019 2 | From the Executive Director THE ROYAL OAK FOUNDATION 20 West 44th Street, Suite 606 New York, New York 10036-6603 212.480.2889 | www.royal-oak.org BOARD OF DIRECTORS Chairman Lynne L. Rickabaugh Vice Chairman Renee Nichols Tucei Treasurer Susan Ollila Montacute House in Somerset is a masterpiece of Elizabethan Renaissance architecture and design. Secretary Royal Oak members visited the house on this year’s annual garden tour. Prof. Sir David Cannadine Directors Cheryl Beall Michael A. Boyd Dear Members & Friends, Michael J. Brown Though we are nearing the final quarter of 2019, our year is far from over. On November Susan Chapman 6, we will host our fall benefit dinner at the Century Association in New York City. This Constance M. Cincotta year’s event will honor the Duke of Devonshire for his contribution to the preservation Robert C. Daum of British culture and the 10 year restoration of Chatsworth. Sir David Cannadine will Tracey A. Dedrick join in discussion with the Duke about his project to restore Chatsworth to its full glory Anne Blackwell Ervin and it promises to be wonderful evening. Pamela K. Hull Linda A. Kelly We are well on our way to achieving our goal of raising $250,000 to preserve the library at Hilary McGrady Blickling Hall. This is one of the most significant libraries under the care of the National Eric J. -

Monks Eleigh Parish Council Minutes of Parish Council

1357 MONKS ELEIGH PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES OF PARISH COUNCIL MEETING ON 31 JULY 2017 The Parish Council Meeting was held on 31 July 2017 at 7.30pm in the Village Hall. Cllr. J Clarke, welcomed the following Parish Councillors –P Derry, D Reynolds, A Forrest, P Day, A Keitley-Webb and the Parish Clerk Nicola Smith. District Councillor Mr Clive Arthey was present. County Councillor Mr Robert Lindsay was on annual leave. 6 members of the public attended the meeting. In accordance with the changes in legislation, the public and councillors were permitted to film, record, photograph or use social media in order to report on the proceedings of the meeting, subject to complying with certain provisions. A full transcript of the statement is available from the Parish Clerk upon request. 1. Apologies for absence: i. County Cllr Robert Lindsay sent his apologies to the meeting he was on annual leave; ii. Not applicable. 2. To receive Members’ Declarations of Interest: i. Cllr Derry declared an interest in items 7ii, 7iv, 10 and 16ii of the Agenda (due to the proximity of her property to the Village Green); ii. No declarations of gifts of hospitality received; iii. Consider requests for dispensation for pecuniary interests for the Agenda under discussion – none. 3. Minutes of Meeting: Clerk apologised to Councillors. She had prepared and had approved by the Chairman the draft Minutes of 22 May 2017 but it transpired at the Meeting that Councillors had not received them. In addition, the Clerk had yet to complete the draft Minutes of 3 July 2017. -

George Abbot 1562-1633 Archbishop of Canterbury

English Book Owners in the Seventeenth Century: A Work in Progress Listing How much do we really know about patterns and impacts of book ownership in Britain in the seventeenth century? How well equipped are we to answer questions such as the following?: What was a typical private library, in terms of size and content, in the seventeenth century? How does the answer to that question vary according to occupation, social status, etc? How does the answer vary over time? – how different are ownership patterns in the middle of the century from those of the beginning, and how different are they again at the end? Having sound answers to these questions will contribute significantly to our understanding of print culture and the history of the book more widely during this period. Our current state of knowledge is both imperfect, and fragmented. There is no directory or comprehensive reference source on seventeenth-century British book owners, although there are numerous studies of individual collectors. There are well-known names who are regularly cited in this context – Cotton, Dering, Pepys – and accepted wisdom as to collections which were particularly interesting or outstanding, but there is much in this area that deserves to be challenged. Private Libraries in Renaissance England and Books in Cambridge Inventories have developed a more comprehensive approach to a particular (academic) kind of owner, but they are largely focused on the sixteenth century. Sears Jayne, Library Catalogues of the English Renaissance, extends coverage to 1640, based on book lists found in a variety of manuscript sources. The Cambridge History of Libraries in Britain and Ireland (2006) contains much relevant information in this field, summarising existing scholarship, and references to this have been included in individual entries below where appropriate. -

Blickling Hall Library Conservation: Building and Environment

BLICKLING HALL LIBRARY CONSERVATION: BUILDING AND ENVIRONMENT HERITAGE DESIGN AND ACCESS STATEMENT JUNE 2018 BROADLAND DISTRICT COUNCIL 17 July 2018 20181176 PLANNING CONTROL Blickling Library – Heritage Design and Access Statement Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 2 List Description........................................................................................................................................ 4 History ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 Library Components ................................................................................................................................ 7 Statement of Significance ....................................................................................................................... 9 Investigations and Reports ................................................................................................................... 13 Heritage Impact Assessment ................................................................................................................ 16 Appendices ............................................................................................................................................ 23 1 Blickling Library – Heritage Design and Access Statement Introduction This document has been prepared in -

Bildeston - Hadleigh 112 Sudbury - Chelsworth 112A MONDAYS, WEDNESDAYS, THURSDAYS & SATURDAYS (Except Public Holidays) From: 16Th April 2012

BEESTONS, TravEL SErviCES Sudbury - Bildeston - Hadleigh 112 Sudbury - Chelsworth 112A MONDAYS, WEDNESDAYS, THURSDAYS & SATURDAYS (Except Public Holidays) From: 16th April 2012 Operator TS TS TS TS BE Service 112 112A 112A 112 112 Notes MW Th Th MW S Sch Sch Sch Sch Sudbury, Bus Station .............................................. 0930 0930 1200 1255 1345 Great Waldingfield, The Heath, opp Post Office ....... 0938 0938 1208 1303 1353 Little Waldingfield, The Street, The Swan ................ 0942 0942 1212 1307 1356 Brent Eleigh, A1141, opp Milden Road ...................... 0949 0949 1219 1314 1403 Monks Eleigh, The Street, The Swan ........................ 0952 0952 1222 1317 1406 Chelsworth, The Street, The Peacock ....................... | 0955 1225 | 1409 Bildeston, Market Place, opp Clock Tower ................ | -- -- | 1420 Semer, B1115, opp Semer Bridge .............................. | -- -- | 1427 Semer, adj Sayers Farm ............................................. 0957 -- -- 1322 | Hadleigh, Calais Street, Buyright ............................... 1007 -- -- 1332 | Hadleigh, Bus Station .............................................. 1009 -- -- 1334 1435 Hadleigh, Highlands Road, High School .................... 1011 -- -- 1336 -- Hadleigh, Bus Station .............................................. 1013 -- -- 1338 -- What the notes mean: MW - Mondays & Wednesdays only S - Saturdays only Sch - Schooldays only Th - Thursdays only Operator Contact: BE - Beestons 01473 823243 TS - Travel Services 01473 341500 Further Information -

Wickham Court and the Heydons Gregory

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society glrcirecoingia Iantinna WICKHAM COURT AND THE HEYDONS By MOTHER MARY GREGORY, L.M., M.A.OxoN. Lecturer in History, Coloma Training College, Wickham Court THE manor of West Wickham in Kent came into the hands of the Heydon family of Baconsthorpe, Norfolk, in the latter years of the fifteenth century. The Heydons, a family which could be classed among the lesser gentry in the earlier part of the century, were in the ascendant in the social scale. The accumulation of manors was a sign of prosperity, and many hitherto obscure families were climbing into prominence by converting the wealth they had obtained through lucrative legal posts into real estate. The story of the purchase of West Wickham by the Heydons and of its sale by them just over a century later provides a useful example of the varying fortunes of a family of the gentry at this date, for less is known about the gentry as a class than of the nobility. John Heydon had prospered as a private lawyer, and his son Henry was the first of the family to be knighted. Henry's father made a good match for him, marrying him into the house of Boleyn, or Bullen, a family which was advancing even more rapidly to prominence. The lady chosen was a daughter of Sir Geoffrey Boleyn, a wealthy mercer who, in 1457, was elected Lord Mayor of London. Sir Geoffrey's grandson married Elizabeth Howard, a daughter of the Duke of Norfolk; his great-granddaughter, Henry Heydon's great-niece, was to be queen of England. -

Notice of Poll Babergh

Suffolk County Council ELECTION OF COUNTY COUNCILLOR FOR THE BELSTEAD BROOK DIVISION NOTICE OF POLL NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN THAT :- 1. A Poll for the Election of a COUNTY COUNCILLOR for the above named County Division will be held on Thursday 6 May 2021, between the hours of 7:00am and 10:00pm. 2. The number of COUNTY COUNCILLORS to be elected for the County Division is 1. 3. The names, in alphabetical order and other particulars of the candidates remaining validly nominated and the names of the persons signing the nomination papers are as follows:- SURNAME OTHER NAMES IN HOME ADDRESS DESCRIPTION PERSONS WHO SIGNED THE FULL NOMINATION PAPERS 16 Two Acres Capel St. Mary Frances Blanchette, Lee BUSBY DAVID MICHAEL Liberal Democrats Ipswich IP9 2XP Gifkins CHRISTOPHER Address in the East Suffolk The Conservative Zachary John Norman, Nathan HUDSON GERARD District Party Candidate Callum Wilson 1-2 Bourne Cottages Bourne Hill WADE KEITH RAYMOND Labour Party Tom Loader, Fiona Loader Wherstead Ipswich IP2 8NH 4. The situation of Polling Stations and the descriptions of the persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows:- POLLING POLLING STATION DESCRIPTIONS OF PERSONS DISTRICT ENTITLED TO VOTE THEREAT BBEL Belstead Village Hall Grove Hill Belstead IP8 3LU 1.000-184.000 BBST Burstall Village Hall The Street Burstall IP8 3DY 1.000-187.000 BCHA Hintlesham Community Hall Timperleys Hintlesham IP8 3PS 1.000-152.000 BCOP Copdock & Washbrook Village Hall London Road Copdock & Washbrook Ipswich IP8 3JN 1.000-915.500 BHIN Hintlesham Community Hall Timperleys Hintlesham IP8 3PS 1.000-531.000 BPNN Holiday Inn Ipswich London Road Ipswich IP2 0UA 1.000-2351.000 BPNS Pinewood - Belstead Brook Muthu Hotel Belstead Road Ipswich IP2 9HB 1.000-923.000 BSPR Sproughton - Tithe Barn Lower Street Sproughton IP8 3AA 1.000-1160.000 BWHE Wherstead Village Hall Off The Street Wherstead IP9 2AH 1.000-244.000 5.