Aviation Occurrence Report Declared Emergency/Wheel Failure Advance Air Charters Mcdonnell Douglas Dc-8-62F C-Fhaa Calgary Inte

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DAO Level 4 Certificate in Applied Aviation Studies (Fixed Wing Aircraft Loadmaster)

Qualification Handbook DAO Level 4 Certificate in Applied Aviation Studies (Fixed Wing Aircraft Loadmaster) QN: 603/0925/8 The Qualification Overall Objective for the Qualifications This handbook relates to the following qualification: DAO Level 4 Certificate Applied Aviation Studies (Fixed Wing Aircraft Loadmaster) This Level 4 Certificate provides the standards that must be achieved by individuals that are working within the Armed Forces. Pre-entry Requirements Entry requirements are detailed in the Course prospectus. Learners who are taking this qualification should be employed in the WSOp trade Unit Content and Rules of Combination This qualification is made up of a total of 16 mandatory units and no Optional units. To be awarded this qualification the candidate must achieve a total of 35 credits as shown in the table below. URN Unit of assessment Level TQT GLH Credit Value D/615/4342 Duties of the WSOp CMN Fixed Wing and associated aircraft 3 7 7 1 K/615/4344 WSOp Regulations 3 16 10 2 T/615/4346 Weight and balance in fixed wing aircraft 4 46 40 5 A/615/4347 Loading and Restraint of Aircraft Cargo 4 42 42 5 F/615/4348 Cargo and Mail in Fixed Wing Operations 4 38 36 4 J/615/4349 Dangerous Goods (DG) on AT & ARR aircraft 4 45 45 5 A/615/4350 Passengers in the AT & ARR aircraft 3 6 6 1 J/615/4352 In–flight catering for WSOp 2 9 9 1 K/615/4361 Regulations of AT & ARR operations 3 25 25 3 M/615/4362 Pre Flying Exercise checks 4 14 14 2 T/615/4363 Radio operation (Crewman) 4 6 6 1 A/615/4364 WSOp (CMN) during aircraft operations (Simulator) 4 6 6 1 F/615/4365 WSOp Crewman procedures 4 9 9 1 J/615/4366 Duties of the WSOp CMN Fixed Wing when away from home base 4 5 5 1 L/615/4367 Principles of aircraft servicing (WSOp) 4 8 8 1 R/615/4368 Agencies associated with WSOP (CMN) operations 3 7 7 1 Age Restriction This qualification is available to learners aged 18+. -

United-2016-2021.Pdf

27010_Contract_JCBA-FA_v10-cover.pdf 1 4/5/17 7:41 AM 2016 – 2021 Flight Attendant Agreement Association of Flight Attendants – CWA 27010_Contract_JCBA-FA_v10-cover.indd170326_L01_CRV.indd 1 1 3/31/174/5/17 7:533:59 AMPM TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1 Recognition, Successorship and Mergers . 1 Section 2 Definitions . 4 Section 3 General . 10 Section 4 Compensation . 28 Section 5 Expenses, Transportation and Lodging . 36 Section 6 Minimum Pay and Credit, Hours of Service, and Contractual Legalities . 42 Section 7 Scheduling . 56 Section 8 Reserve Scheduling Procedures . 88 Section 9 Special Qualification Flight Attendants . 107 Section 10 AMC Operation . .116 Section 11 Training & General Meetings . 120 Section 12 Vacations . 125 Section 13 Sick Leave . 136 Section 14 Seniority . 143 Section 15 Leaves of Absence . 146 Section 16 Job Share and Partnership Flying Programs . 158 Section 17 Filling of Vacancies . 164 Section 18 Reduction in Personnel . .171 Section 19 Safety, Health and Security . .176 Section 20 Medical Examinations . 180 Section 21 Alcohol and Drug Testing . 183 Section 22 Personnel Files . 190 Section 23 Investigations & Grievances . 193 Section 24 System Board of Adjustment . 206 Section 25 Uniforms . 211 Section 26 Moving Expenses . 215 Section 27 Missing, Interned, Hostage or Prisoner of War . 217 Section 28 Commuter Program . 219 Section 29 Benefits . 223 Section 30 Union Activities . 265 Section 31 Union Security and Check-Off . 273 Section 32 Duration . 278 i LETTERS OF AGREEMENT LOA 1 20 Year Passes . 280 LOA 2 767 Crew Rest . 283 LOA 3 787 – 777 Aircraft Exchange . 285 LOA 4 AFA PAC Letter . 287 LOA 5 AFA Staff Travel . -

Federal Aviation Administration Administration

Federal Aviation Federal Aviation Administration Administration Cargo Focus Team And Air Cargo Operations Presented to: EMI FSDO Operators By: AFS-330 Date: February 2016 Overview Background Cargo Focus Team . NTSB . Working with Stakeholders . Short and Long Term Goals . Accomplishments . AC 120-85A Highlights Cargo Operations Changes to the AFM/WBM Current Issues and Initiatives February 2016 Cargo Focus Team Federal Aviation 2 Administration Background Cargo Aircraft Accident likelihood 20 times more likely than a passenger aircraft (according to IATA data) FAA CAST team is currently showing 30 to 50 February 2016 Cargo Focus Team Federal Aviation 3 Administration Background Following the Air Cargo accident in Afghanistan, a team was assembled to determine whether or not systemic problems exist regarding special cargo loads Aircraft Certification (AIR) and Flight Standards (AFS) are working jointly to address Cargo Operation with a focus on “Special Cargo” February 2016 Cargo Focus Team Federal Aviation 4 Administration Cargo Focus Team The FAA, Cargo Focus Team (CFT) exists as a permanent technical resource for cargo operations For cargo operations questions or suggestions contact CFT @ [email protected] February 2016 Cargo Focus Team Federal Aviation 5 Administration Cargo Focus Team Team Structure Interdependency Multi Discipline . Transport Airplane Directorate (ANM-100) . Air Transport Operations (AFS-200) . Aircraft Maintenance Division (AFS-300) . National Field Office (AFS-900) . Field Inspector (CMO- Detailees) February 2016 Cargo Focus Team Federal Aviation 6 Administration Cargo Focus Team The CFT Vision is to enhance the safety of air cargo operations. The CFT Mission is to directly support FAA field personnel, act as a focal point for the integrity of air cargo operations while serving as the FAA’s technical matter expert in air cargo operations February 2016 Cargo Focus Team Federal Aviation 7 Administration NTSB NTSB final report on from B-747 accident published July 29, 2015. -

Civilian Involvement in the 1990-91 Gulf War Through the Civil Reserve Air Fleet Charles Imbriani

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 Civilian Involvement in the 1990-91 Gulf War Through the Civil Reserve Air Fleet Charles Imbriani Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCE CIVILIAN INVOLVEMENT IN THE 1990-91 GULF WAR THROUGH THE CIVIL RESERVE AIR FLEET By CHARLES IMBRIANI A Dissertation submitted to the Interdisciplinary Program in the Humanities in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2012 Charles Imbriani defended this dissertation on October 4, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Peter Garretson Professor Directing Dissertation Jonathan Grant University Representative Dennis Moore Committee Member Irene Zanini-Cordi Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to Fred (Freddie) Bissert 1935-2012. I first met Freddie over forty years ago when I stared working for Pan American World Airways in New York. It was twenty-two year later, still with Pan Am, when I took a position as ramp operations trainer; and Freddie was assigned to teach me the tools of the trade. In 1989 while in Berlin for training, Freddie and I witnessed the abandoning of the guard towers along the Berlin Wall by the East Germans. We didn’t realize it then, but we were witnessing the beginning of the end of the Cold War. -

Operations Group Chairman's Factual Report

NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY BOARD Office of Aviation Safety Washington, D.C. 20594 October 30, 2014 Group Chairman’s Factual Report OPERATIONAL FACTORS DCA13MA081 1 OPS FACTUAL REPORT DCA13MA081 Table Of Contents A. ACCIDENT ............................................................................................................................ 4 B. OPERATIONAL FACTORS GROUP ................................................................................... 4 C. SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................ 5 D. DETAILS OF THE INVESTIGATION ................................................................................. 5 E. FACTUAL INFORMATION ................................................................................................. 6 1.0 History of Flight .............................................................................................................. 6 2.0 Flight Crew Information ................................................................................................. 9 2.1 The Captain ............................................................................................................... 10 2.1.1 The Captain’s Pilot Certification Record ............................................................ 11 2.1.2 The Captain’s Certificates and Ratings Held at Time of the Accident ............... 11 2.1.3 The Captain’s Training and Proficiency Checks Completed .............................. 11 2.1.4 The Captain’s -

Commercial Aviation Safety Team WHITE HOUSE COMMISSION on AVIATION SAFETY and the NATIONAL CIVIL AVIATION REVIEW COMMISSION (NCARC)

Commercial Aviation Safety Team WHITE HOUSE COMMISSION ON AVIATION SAFETY AND THE NATIONAL CIVIL AVIATION REVIEW COMMISSION (NCARC) 1.1 . Reduce Fatal Accident Rate . •. Strategic Plan to Improve Safety . •. Improve Safety Worldwide . CAST BRINGS TOGETHER KEY STAKEHOLDERS TO COOPERATIVELY DEVELOP AND IMPLEMENT A PRIORITIZED SAFETY AGENDA. Industry Government A4A DOD AIA FAA Airbus NASA ALPA ICAO** ACI–NA Commercial Aviation CAPA TCCA IATA** Safety Team NATCA NACA NTSB** Boeing EASA** GE* RAA FSF * Representing P&W and RR ** Observer CAST GOAL CAST came together in 1997 to form an unprecedented industry-Government partnership. Voluntary commitments, data-driven risk management, implementation-focused. Goal: Original Reduce the US commercial aviation fatal accident rate 80% by 2007. New Reduce the U.S. commercial aviation fatality risk by at least 50% from 2010 to 2025. CAST SAFETY STRATEGY Data Implement Safety Analysis Enhancements (SE) – United States Set Safety Priorities Agree on problems and interventions Influence SEs – Achieve consensus on Worldwide priorities Integrate into existing work and distribute RESOURCE COST VS. RISK REDUCTION 100% 10000 Risk Reduction APPROVED PLAN 9000 $ Total Cost in $ (Millions) 8000 75% 7000 6000 50% $ 5000 2007 2020 4000 3000 25% Resource Cost ($ Millions) Resource 2000 Risk Eliminated by Safety Enhancements 1000 $ $ $ 0% 0 COST SAVINGS Part 121 Aviation Industry Cost Due to Fatal/Hull Loss Accidents Historical cost of 100 accidents per flight cycle 80 Savings ~ $71/Flight Cycle 60 or ~ $852 Million -

USFS MAFFS Operating Plan

6 August 2019 Operations MAFFS OPERATING PLAN OPERATIO NS AUTHORITIES AND INSTRUMENTS .MODULAR AIRBORNE FIRE FIGHTING SYSTEM (MAFFS) DEPLOYMENT, OPERA TIO NS AND TRAINING Paul Linse Reviewed By: MAFFS Training Officer, Depl!-tY/4 ssistant Director, Operations - NIFC Kim Christensen .J><f - �- - b/: � _ '- .J CertifiedBy: Assistant Director,_ Aviation- W eadquarters t JeffPower / I . µ), // - ----------- -- Certified By: National MLO, Assistant Director forOperations - NIFC BethLund �� Supersedes 2016 MAFFS Operating Plan Distribution: USFS/F AM, BLM/A VN, NGB/A3, AFRC/ A3, AMC/ A3, AEG/CC, CAL FIRE 2 6 AUGUST 2019 ACCESSIBILITY: This publication is available digitally on the National Interagency Coordination Center web site https://www.nifc.gov/nicc/logistics/references/MAFFS_Operations_Plan .pdf. RELEASABILITY: Attachment 4 contains PII, shall not be released to the general public, and shall only be made available to authorized personnel. This instruction implements Forest Service Operations Guidelines for the Modular Airborne Fire Fighting Systems (MAFFS) training and operations program. It provides guidance regarding the activation, operation, and training; and outlines actions associated with MAFFS operations. This publication applies to Air National Guard (ANG) Wings and Air Force Reserve (AFRC) Wings authorized for MAFFS deployment and agency employees holding the appropriate wildland firefighting certifications for MAFFS operations. Restrictions in this document may only be waived by the NMLO or Deputy NMLO unless otherwise specified. The attachments in this publication may be updated individually without the update of the whole instruction and will be dated accordingly to ensure that the most current copy of the attachment is referenced for operational purposes. A supplement to this instruction may be issued with each update. -

1 Introduction to Cabin Crew Background the World of Flight Attendants Has Changed Significantly Since the Beginning of Commercial Air Travel

1 Introduction to cabin crew Background The world of flight attendants has changed significantly since the beginning of commercial air travel. The first airliners were actually mail planes with a few extra spaces for passengers. The only crew were the pilots. Eventually, some early airlines added ‘cabin boys’ to their flights. These crew members, who were usually young men, were mainly on board to load luggage, reassure nervous passengers, and help people get around the plane. Imperial Airways of the United Kingdom had ‘cabin boys’ or ‘stewards’ in the 1920s. In the USA, Stout Airways was the first to employ stewards in 1926. Western Airlines (1928) and Pan American World Airways (1929) were the first US carriers to employ stewards to serve food. The first female flight attendant was 25-year-old registered nurse, Ellen Church, hired by Boeing in 1930. Until relatively recently, airline stewardesses were subject to strict regulations. They were not allowed to be married and most airlines had certain constraints on their height, weight, and proportions. Their clothing was similarly restrictive: at many airlines, stewardesses wore form-fitting uniforms and were required to wear white gloves and high heels throughout the flight. While it was a perfectly respectable occupation for young women, early stewardesses were generally underpaid, had minimal benefits, and were in a subservient role to pilots. During the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s, flight-attendant unions, as well as representatives from the equal rights movement, brought about sweeping changes in the airline industry that addressed these problems. Since the 1970s, the policy of the major airlines has been to hire both men and women as flight attendants and to have minimal restrictions on size and weight. -

The Undisputed Leader in World Travel CONTENTS

Report & Accounts 1996-97 ...the undisputed leader in world travel CONTENTS Highlights of the year 1 Chairman’s Statement 2 THE NEXT Chief Executive’s Statement 5 Board Members 8 The Board and Board Committees DECADEIN FEBRUARY 1997 and the Report of the Remuneration Committee 10 British Airways celebrated 10 years of privatisation, with a Directors’ Report 14 renewed commitment to stay at the forefront of the industry. Report of the Auditors on Corporate Governance matters 17 Progress during the last decade has been dazzling as the airline Operating and Financial established itself as one of the most profitable in the world. Review of the year 18 Statement of Directors’ responsibilities 25 Report of the Auditors 25 Success has been built on a firm commitment to customer service, cost control and Group profit and loss account 26 the Company’s ability to change with the times and new demands. Balance sheets 27 As the year 2000 approaches, the nature of the industry and Group cash flow statement 28 competition has changed. The aim now is to create a new Statement of total recognised British Airways for the new millennium, to become the undisputed gains and losses 29 leader in world travel. Reconciliation of movements in shareholders’ funds 29 This involves setting a new direction for the Company with a Notes to the accounts 30 new Mission, Values and Goals; introducing new services and Principal investments 54 products; new ways of working; US GAAP information 55 new behaviours; a new approach to The launch of privatisation spelt a Five year summaries 58 service style and a brand new look. -

Air Force Transitions to a Single Combat Uniform

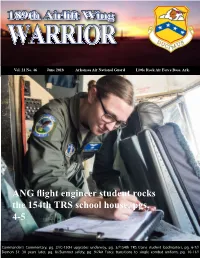

189th Airlift Wing WARRIOR Vol. 21 No. 46 June 2018 Arkansas Air National Guard Little Rock Air Force Base, Ark. ANG flight engineer student rocks the 154th TRS school house, pgs. 4-5 Commander’s Commentary, pg. 2//C-130H upgrades underway, pg. 3//154th TRS trains student loadmasters, pg. 6-7// Demon 51: 30 years later, pg. 8//Summer safety, pg. 9//Air Force transitions to single combat uniform, pg. 10-11// 2 Warrior, June 2018 Warrior, June 2018 3 www.facebook. Commander’s Commentary com/189AW C-130H upgrades underway By Col. Thomas D. Crimmins www.instagram. 189th Airlift Wing Commander com/189AW reetings Warriors! We have a very busy super UTA this month, followed Publication Staff Gby our Annual Training in Gulfport, MS. If you can’t tell already, the heat has arrived and summer is already here in Arkansas. With Memorial Day behind Col. Thomas D. Crimmins 189th Airlift Wing us, summer activities are now in full swing. Please remember to stay hydrated, Commander use appropriate personal protective equipment (including sunscreen), and obey all applicable laws and safety guidelines for your specific form of recreation. VACANT As you all know, the Chief of Staff of the Air Force and Director of the Air Public Affairs Officer National Guard have directed an Air Force-wide Safety Stand Down to pause and Tech Sgt. Jessica Condit reflect on our safety culture and practices in light of recent mishaps. We will take Public Affairs Superintendent the entire day Sunday to focus on safety in all areas -operational, personal and Senior Airman Kayla K. -

Ground Operations Officer & Loadmaster

Ground Operations Officer & Loadmaster Location Description of the position LGG, Liege Airport (Belgium) The Ground Operations Officer & Loadmaster assists the Ground Operations Department in day-to-day operations and acts as company loadmaster. Corporate responsibilities: About Challenge Supervise all cargo handling operations at home base (LGG) and Airlines (BE) outstations; Challenge Airlines (BE) Supervise cargo build-up, loading and offloading of company aircraft; S.A. is a new airline Act as company loadmaster on B747-400BCF/ERF; Assist in day-to-day Ground Operations tasks; based in Liege Airport (LGG) with a Belgian Act as Challenge Airlines (BE) Ground Operations Representative on AOC. The airline operates charter flights when needed; daily scheduled cargo Ensure and monitor compliance with Ground Operations Procedures flights and charter considering safety, quality and On Time Performance; services carrying Assist in composing handling and airport cost quotations. nonstandard goods and general cargo internationally. Challenge . Technical responsibilities: Airlines (BE) is part of a Proper use of Aviation industry and Aviation terminology; Global airline group that Application of precise and correct weight and balance procedures; carries approximately Supervision and guidance towards proper use of the company Aircraft 200,000 tons of cargo Cargo Loading System; annually. The Group is in Oversight and ownership of the safe and careful use of company aircraft rapid growth and is during loading and unloading processes. -

Collective Bargaining Agreement

COLLECTIVE BARGAINING AGREEMENT between the STATE OF ALASKA and the INLANDBOATMEN’S UNION of the PACIFIC ALASKA REGION 2014 – 2017 Table of Contents RULE 1 - SCOPE ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.04 - Labor Management Committee Purpose .................................................................................................................... 1 RULE 2 - RECOGNITION ......................................................................................................................................... 2 RULE 3 - HIRING .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 RULE 4 - DEFINITIONS ............................................................................................................................................ 2 4.01 - Employees ................................................................................................................................................................ 2 4.02 - Regularly Assigned Positions .................................................................................................................................... 3 4.03 - Vessels ..................................................................................................................................................................... 3 RULE 5 - UNION MEMBERSHIP .........................................................................................................................