The Transformation of Australian Foreign Policy Towards the European Union

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

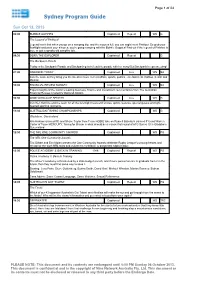

Sydney Program Guide

Page 1 of 24 Sydney Program Guide Sun Oct 13, 2013 06:00 BUBBLE GUPPIES Captioned Repeat WS G The Legend of Pinkfoot! Legend has it that when you go on a camping trip, and the moon is full, you just might meet Pinkfoot. So grab your flashlight and pack your s’mores; you’re going camping with the Bubble Guppies! Find out if the legend of Pinkfoot is true, or just a spooky old campfire tale. 06:30 DORA THE EXPLORER Captioned Repeat G The Backpack Parade Today is the Backpack Parade and Backpack gets to lead the parade with her song! But Backpack keeps sneezing! 07:00 WEEKEND TODAY Captioned Live WS NA Join the team as they bring you the latest in news, current affairs, sports, politics, entertainment, fashion, health and lifestyle. 10:00 FINANCIAL REVIEW SUNDAY Captioned Live WS NA Expert insights of the nation’s leading business, finance and investment commentators from The Australian Financial Review, hosted by Deborah Knight. 10:30 WIDE WORLD OF SPORTS Captioned Live WS G Join Ken Sutcliffe and the team for all the overnight news and scores, sports features, special guests and light- hearted sporting moments. 11:30 AUSTRALIAN FISHING CHAMPIONSHIPS Captioned WS G Gladstone, Queensland Kris Hickson (ranked #3) and Shane Taylor from Team HOBIE take on Russell Babekuhl (ranked #1) and Warren Carter of Team MERCURY, fishing for Bream in what should be a classic first round of AFC Series 10 in Gladstone, Queensland 12:00 THE NRL ONE COMMUNITY AWARDS Captioned WS PG The NRL One Community Awards Tim Gilbert and Erin Molan present the One Community Awards celebrate Rugby League’s unsung heroes and recognise the work NRL stars and volunteers contribute to grassroots rugby league. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’S Eve 2018 – the Night Is Yours

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’s Eve 2018 – The Night is Yours. Image: Jared Leibowtiz Cover: Dianne Appleby, Yawuru Cultural Leader, and her grandson Zeke 11 September 2019 The Hon Paul Fletcher MP Minister for Communications, Cyber Safety and the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Minister The Board of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation is pleased to present its Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2019. The report was prepared for section 46 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, in accordance with the requirements of that Act and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Act 1983. It was approved by the Board on 11 September 2019 and provides a comprehensive review of the ABC’s performance and delivery in line with its Charter remit. The ABC continues to be the home and source of Australian stories, told across the nation and to the world. The Corporation’s commitment to innovation in both storytelling and broadcast delivery is stronger than ever, as the needs of its audiences rapidly evolve in line with technological change. Australians expect an independent, accessible public broadcasting service which produces quality drama, comedy and specialist content, entertaining and educational children’s programming, stories of local lives and issues, and news and current affairs coverage that holds power to account and contributes to a healthy democratic process. The ABC is proud to provide such a service. The ABC is truly Yours. Sincerely, Ita Buttrose AC OBE Chair Letter to the Minister iii ABC Radio Melbourne Drive presenter Raf Epstein. -

Sydney Program Guide

Page 1 of 19 Sydney Program Guide Sun Jun 26, 2016 06:00 PAW PATROL Captioned Repeat HD WS G A pack of six heroic puppies and a tech-savvy 10-year-old boy work together using a unique blend of problem- solving skills, cool vehicles and lots of cute doggy humour on high-stakes rescue missions to protect the Adventure Bay community. 06:30 DORA THE EXPLORER Captioned Repeat WS G Vamos A Pintar Dora and Boots are painting pictures in Dora's yard when suddenly, they hear crying. In the nearby forest, they discover Pincel, a paintbrush who's crying multi-colored tears. He needs their help getting back to the Art Studio! 07:00 WEEKEND TODAY Captioned Live HD WS NA Join the Weekend Today team as they bring you the latest in news, current affairs, sports, politics, entertainment, fashion, health and lifestyle. 10:00 WIDE WORLD OF SPORTS Captioned Live HD WS PG Join Ken Sutcliffe, Emma Freedman and the team for all the overnight news and scores, sports features, special guests and light-hearted sporting moments. 11:00 SUNDAY FOOTY SHOW Captioned Live HD WS PG Breaking NRL news, expert analysis, high profile guests taking you to places and people no ticket can buy. Hosted by Yvonne Sampson. 13:00 SUBARU FULL CYCLE Captioned HD WS NA Hosted by two of Australia’s most coveted former cyclists Scott McGrory and Bradley McGee who will keep fans up to date with all the news & action on the road and behind the scenes at the Subaru National Road Series. -

Sydney Program Guide

Page 1 of 42 Sydney Program Guide Sun Mar 14, 2021 06:00 EASY EATS Captioned HD WS G Nutritious & Delicious In this episode of Easy Eats, everything is gorgeous and guilt-free. Dishes like Lamb Stir Fry, Vegie Strudel, and Sweet Corn Soup are low in fat but high in flavour. There's even a low fat version of Hummingbird Cake which is perfect for those watching their waistline. 07:00 WEEKEND TODAY Captioned Live HD WS NA Join the Weekend Today team as they bring you the latest in news, current affairs, sports, politics, entertainment, fashion, health and lifestyle. 10:00 SPORTS SUNDAY Captioned Live HD WS PG Featuring Australia's leading sports personalities, Sports Sunday presents a frank and open debate about all the issues in the week of sport, with the promise of heated opinion and a few laughs along the way. 11:00 SUNDAY FOOTY SHOW Captioned Live HD WS PG Join hosts Peter Sterling, Erin Molan and Brad Fittler, with regular special guests to discuss all things NRL. 13:00 WOMEN'S FOOTY Captioned HD WS PG Join Bianca Chatfield for the 5th Season of Women's Footy for the latest news, opinion and analysis from in and around the AFLW - Each week, a raft of the AFLW's biggest names will join the show to discuss the weekend's action. 14:00 DAVID ATTENBOROUGH'S DYNASTIES Captioned Repeat HD WS PG The Making of Dynasties Follow five of the world's most celebrated, yet endangered animals: penguins, chimpanzees, lions, painted wolves and tigers, as they fight for their own survival and for the future of their dynasties. -

Download Program

Festival Guests Festival Information Sponsors Amanda Anastasi is an award-winning poet writer of the The Treehouse series and the in Residence at Melbourne University, Janet How to Book Festival Venues Major Partners Williamstown Literary whose work ranges from the introspective to BUM trilogy. Clarke Hall. willy All events held on Saturday 13 June the socio-political. Gideon Haigh has been an independent Susan Pyke teaches with the University of For detailed descriptions of sessions, David Astle is the Dictionary Guy on Letters journalist for almost 30 years. Melbourne, and her poetry, short stories and presenters and to book tickets, visit and Sunday 14 June are located at either the Williamstown Town Hall www.willylitfest.org.au or phone the ( and Numbers (SBS) and well-known crossword John Harms is a writer, publisher, broadcaster associative essays have appeared in various Festival lit compiler. and historian who appears on Offsiders (ABC) journals. Box Office on 9932 4074. or the Williamstown Library. ‘’ Kate Atkinson is an actor and one of the and runs footyalmanac.com.au Jane Rawson was formerly the Environment Book before midnight, Sunday 24 May Both are located at 104 Ferguson original founders of Actors for Refugees. & Energy Editor for news website, The Catherine Harris is an award-winning writer 2015 for special early bird pricing. Street, Williamstown. Please check 13 and 14 June 2015 fest Matt Blackwood has won multiple awards for and author of The Family Men. Conversation. She is the author of the novel, A Wrong Turn at the Office of Unmade Lists. your ticket for room details. -

Is the Government Listening? Now That the Uproar and Shouting About Alleged Bias Has Died Down, There Is Only One Issue Paramount for the ABC - Funding

Friends of the ABC (NSW) Inc. qu a rt e r ly news l e t t e r Se ptember 2005 Vol 15, No. 3 in c o rp o rat i n g ba ck g round briefing na tional magaz i n e up d a t e friends of the abc Is the Government listening? Now that the uproar and shouting about alleged bias has died down, there is only one issue paramount for the ABC - funding. The corporation has not been backward putting its case forward - notably the collapse of drama production to just 20 hours per annum. In the Melbourne Age, Director of ABC TV Sandra Levy referred to circumstances as "critical and tragic." around, low-cost end - we've pretty "We have all those important well done everything we can." obligations to indigenous programs, religious programs, science, arts, Costs up children’s programs ... things that the dramatically commercial networks don't, and yet Once the launch pad for great we probably battle along with about Australian drama, revelations that the a quarter of what they spend in a ABC's drama output has dwindled year - the disproportion is massive." from 100 hours four years ago to just Ms Levy's concerns have been 14 hours this year have received a lot echoed by managing director Russell of media attention. Balding and chairman Donald Ms Levy estimates that an hour McDonald, who have spent the past could cost anywhere from $500,000 few weeks publicly lamenting the to $2 million, 10 to 50 times more gravity of the funding crisis. -

Annual Report 2009-2010 • 3 6.30AM I Wake up All Wet

St Vincent de Paul Society NSW 2009-2010 AnnuAl RepoRt The Annual Report of the St Vincent de Paul Society NSW is produced by the Community and Corporate Relations Team of the St Vincent de Paul Society NSW, November 2010. Written by: Marion Frith, Communications Manager Edited by: Julie McDonald, Manager, Community and Corporate Relations, [email protected] Design by: Claudia Williams, Publications and Design Coordinator, [email protected] Statistics collated by: Jey Natkunaratnam, Senior Statistics Officer, [email protected] Responsibility for this document rests with the Provisional Board of the St Vincent de Paul Society NSW. Privacy Statement: Because the St Vincent de Paul Society NSW respects the privacy of the people it serves, the names of any clients featured in this report have been changed and pictorial models used. Distributed by Ozanam Industries, www.ozanam.org.au, a Special Work of the St Vincent de Paul Society NSW St Vincent de Paul Society NSW ABN: 46 472 591 335 Auditor: Grant Thornton Bank: Commonwealth Bank of Australia Solicitor: Hunt & Hunt CONTENTS CONTENTS 1.0 Message from the Cardinal.......................................................... 5 2.0 Message from the Chair ............................................................... 7 3.0 Introduction ................................................................................... 8 3.1 Membership and Assistance ..................................................... 10 Central Councils 4.1 Armidale ..................................................................................... -

All Sugar & Spice

FREE SEPTEMBER 2013 > Dural > Mid-Dural > Round Corner > Kellyville > Annangrove > Kenthurst > Glenhaven > Arcadia > Glenorie > Galston All Sugar & Spice See page 3 www.duralchamber.com.au Celebrate our 50th Birthday with us . $PeCiALS across the RANGe! Visit our new Website www.hdfe.com.au buy Kubota Parts online $ave time and $ave money. from $6,490 New Kubota ZG100 Series. Arriving October 2013. Limited stock available, pre-order now to avoid disappointment. 598 Old Northern Road Dural NSW 2158 www.hdfe.com.au Ph: 9651 1896 PRESIDENT’S REPORT Chamber leads the way By Peter Dawson On 28 August the Chamber hosted the only public forum attended by all seven candidates for the seat of Berowra or their representative. fter the Mayor of the Hills Shire, Dr Michelle Byrne, gave the A audience a quick update on the latest issues faced by the Council, MC Tim Webster invited Michael Stove of the Labor Party, John Storey from the Greens, the Palmer United Party’s Paul Graves, Matt Cross representing Phillip Ruddock for the Liberals, Independent Mick Gallagher, Leighton Thew from the Christian Democrats and Deborah Smythe of the Stable Population Party to present their policies and to answer questions from the floor. The discussion was lively, entertaining and sharp, and each of the candidates stood up well to the occasion. Our thanks to The Hills Grammar School for providing the venue and for the excellent catering, and my congratulations to the Chamber’s Liz Pellinkhof, Rod Cuevas and Paul Pixton for their organisation of the event. Tim Webster was in excellent form and I recommend that you catch his Weekend Afternoon show on 2UE for expert advice on everything you need to complete your week - from gardening to motoring, food and wine, travel, money and lots more. -

Ministerial Careers and Accountability in the Australian Commonwealth Government / Edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis

AND MINISTERIAL CAREERS ACCOUNTABILITYIN THE AUSTRALIAN COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT AND MINISTERIAL CAREERS ACCOUNTABILITYIN THE AUSTRALIAN COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT Edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Ministerial careers and accountability in the Australian Commonwealth government / edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis. ISBN: 9781922144003 (pbk.) 9781922144010 (ebook) Series: ANZSOG series Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Politicians--Australia. Politicians--Australia--Ethical behavior. Political ethics--Australia. Politicians--Australia--Public opinion. Australia--Politics and government. Australia--Politics and government--Public opinion. Other Authors/Contributors: Dowding, Keith M. Lewis, Chris. Dewey Number: 324.220994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents 1. Hiring, Firing, Roles and Responsibilities. 1 Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis 2. Ministers as Ministries and the Logic of their Collective Action . 15 John Wanna 3. Predicting Cabinet Ministers: A psychological approach ..... 35 Michael Dalvean 4. Democratic Ambivalence? Ministerial attitudes to party and parliamentary scrutiny ........................... 67 James Walter 5. Ministerial Accountability to Parliament ................ 95 Phil Larkin 6. The Pattern of Forced Exits from the Ministry ........... 115 Keith Dowding, Chris Lewis and Adam Packer 7. Ministers and Scandals ......................... -

2019 Economic and Political Overview in Brisbane

2019 Economic and Political Overview in Brisbane Thursday 14 February 2019, 10.00am to 2.00pm Brisbane Convention and Exhibition Centre EVENT MAJOR SPONSOR www.ceda.com.au morning agenda 10.00am Registration 10.15am Welcome Kyl Murphy State Director and Company Secretary, CEDA 10.25am Speaker address Michael Blythe Chief Economist and Managing Director, Economics, Commonwealth Bank of Australia 10.45am Speaker address Sara James, Journalist and author 11.00am Speaker address Peter van Onselen Journalist and Professor of Politics and Policy, Griffith Business School 11.15am Close of morning session Kyl Murphy State Director, CEDA . lunch agenda 11.55am Welcome (back) Kyl Murphy State Director and Company Secretary, CEDA 12.00pm Introduction Professor Nick James Executive Dean, Faculty of Law, Bond University 12.10pm Speaker address Professor Simon Jackman Chief Executive Officer, United States Studies Centre 12.25pm Speaker address Peter Varghese AO Chancellor, The University of Queensland 12.40pm Lunch 1.10pm Moderated discussion and questions Moderator: Melinda Cilento, Chief Executive, CEDA • Michael Blythe, Chief Economist and Managing Director, Economics, Commonwealth Bank of Australia • Professor Simon Jackman, Chief Executive Officer, United States Studies Centre • Sara James, Journalist and author • Peter van Onselen, Journalist and Professor of Politics and Policy, Griffith Business School • Peter Varghese AO, Chancellor, The University of Queensland 1.50pm Close Kyl Murphy CEDA will be tweeting from this State Director and Company Secretary, CEDA event using #EPO2019 Join the conversation and follow us on Twitter @ceda_news sponsor Event major sponsor Bond University A student experience powerfully focused on the individual. Our programs are geared towards inspiring students to achieve beyond their expectations - and to strive to pursue their dreams and aspirations. -

Budget 2017: ABC Coverage on TV, Iview, Radio and Online

Media Release: 05.05.17 Budget 2017: ABC Coverage on TV, iview, radio and online abc.net.au/news The 2017 Federal Budget will be handed down on Tuesday May 9 and the ABC has the best independent coverage on all platforms. We’ll have the first interview with Treasurer Scott Morrison, as well as in-depth analysis and expert commentary from the ABC’s leading political and business teams. What does Budget 2017 mean for you? Know the numbers, the politics, and the impact with ABC NEWS. Tuesday, 9 May – BUDGET DAY TELEVISION – ABC, the ABC NEWS channel & iview The Drum - 5.30pm on ABC & iview / 6.30pm AEST on the ABC NEWS channel As the press gallery bunkers down in the budget media lock-up, host John Barron and a panel of experts will count down to Budget 2017 and preview what to expect. ABC NEWS - 7pm on ABC & iview The news of the day and the lead up to the Federal Treasurer’s Budget speech. ABC NEWS BUDGET 2017 SPECIAL - on ABC, the ABC NEWS channel, iview, ABC NEWS online and simulcast live on the ABC News Facebook page. Leigh Sales hosts the ABC NEWS Budget 2017 special with Political Editor Chris Uhlmann live from Parliament House in Canberra. At 7:30pm AEST the Federal Treasurer Scott Morrison will deliver his second Federal Budget speech live from the House of Representatives. Just after 8pm, Federal Treasurer Scott Morrison will join Leigh Sales for his first interview of the night, followed by the response from the Opposition’s Shadow Treasurer Chris Bowen. -

22. Gender and the 2013 Election: the Abbott 'Mandate'

22. Gender and the 2013 Election: The Abbott ‘mandate’ Kirsty McLaren and Marian Sawer In the 2013 federal election, Tony Abbott was again wooing women voters with his relatively generous paid parental leave scheme and the constant sight of his wife and daughters on the campaign trail. Like Julia Gillard in 2010, Kevin Rudd was assuring voters that he was not someone to make an issue of gender and he failed to produce a women’s policy. Despite these attempts to neutralise gender it continued to be an undercurrent in the election, in part because of the preceding replacement of Australia’s first woman prime minister and in part because of campaigning around the gender implications of an Abbott victory. To evaluate the role of gender in the 2013 election, we draw together evidence on the campaign, campaign policies, the participation of women, the discursive positioning of male leaders and unofficial gender-based campaigning. We also apply a new international model of the dimensions of male dominance in the old democracies and the stages through which such dominance is overcome. We argue that, though feminist campaigning was a feature of the campaign, traditional views on gender remain powerful. Raising issues of gender equality, as Julia Gillard did in the latter part of her prime ministership, is perceived as electorally damaging, particularly among blue-collar voters. The prelude to the election Gender received most attention in the run-up to the election in 2012–13 rather than during the campaign itself. Prime Minister Julia Gillard’s famous misogyny speech of 2012 was prompted in immediate terms by the Leader of the Opposition drawing attention to sexism in what she perceived as a hypocritical way.