Woodhead Gully Blocking Monitoring Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peaks Sub-Region Climate Change Study

Peak Sub-Region Climate Change Study Focussing on the capacity and potential for renewables and low carbon technologies, incorporating a landscape sensitivity study of the area. Final Report July 2009 ! National Energy Foundation "#$ % &' !' ( # ) ( * )(+,$- " ,++++ ./.. Land Use Consultants 0%# 1 $2& " 3,+3,0 . *.4. CONTENTS )!5$ 6" 1 Executive Summary.................................................................................................... 7 2 Study Background and Brief ................................................................................... 11 !7*84'*/#* ............................................................................................. 94.............................................................................................................................. 4 /#* ................................................................................................................... ! 4# ................................................................................................................................. 6 * .................................................................................................................................... 0 4/#* ............................................................................................................. 0 *# ................................................................................... + 3 Policy Context.......................................................................................................... -

Peakland Guardian Spring and Summer 2019

For everyone who loves the Peak District Peakland guardian Spring and Summer 2019 Also protecting the landscapes of South Yorkshire In this issue… Follow us on social media Welcome from the CEO experience to the Board, and has already put his Welcome from the CEO 3 We’re being proactive on Facebook, Instagram shoulder to the wheel in helping maximise media By the time this issue goes to print the nation opportunities for some of our campaigns. Seventy years ago 4 and Twitter. If you’re already a fan, please do ❤ should know whether Brexit happened, and if The Friends are sponsoring a significant lecture Wetton Green Lane 6 follow, share, like and ‘ ’ us. Thanks it did, we will continue to work to understand by Julian Glover (leading the government’s review Green Lane art books 6 friendsofthepeakdistrict the ramifications for the landscapes, and the of designated landscapes) at Buxton International Take Back the Tracks 7 communities, of the Peak District and South @friendsofthepeak Festival on 12 July in which he will discuss the Transport for the North 8 Yorkshire. value of national parks. We will have a stand at the HS2 9 friendsofpeak In addition to responding to the Review of festival too. The AGM will be held on 14 August at Losses to the UK’s oldest green belt 10 National Parks and AONBs, the re-branding of the Victoria Centre (in the church next door to our New plans for the Hepworth’s site 12 CPRE, and being involved in the planning for the office in Sheffield). -

Stalybridge to Woodhead 4ZO OHL (March, 2012), Although No Specific Detail Is Given As to the Requirement for Access Works

Stalybridge - Woodhead (4ZO) OHL Level 1: Archaeological and Cultural Heritage Appraisal Submitted to: Electricity Alliance West Submitted by: AMEC Environment and Infrastructure UK Limited Shrewsbury, UK AMEC Project: 32430 October 2012 5 October 2012 AMEC Ref No: 32430 Dear Sir/Madam Re: Stalybridge – Woodhead (4ZO) OHL Please find enclosed the Level 1: Archaeological and Cultural Heritage Appraisal report for the above project. If you have any questions regarding the project please contact the undersigned. Yours sincerely, Robert Johns Senior Consultant AMEC Environment & Infrastructure UK Ltd Canon Court Abbey Lawn Abbey Foregate Shrewsbury SY2 5DE Tel: +44 (0)1743 342029 Reviewed by: Ken Whittaker Associate Director AMEC Environment & Infrastructure UK Ltd 17 Angel Gate City Road London EC1V 2SH Tel: (020) 7843 1468 Electricity Alliance West Refurbishment Works October 2012 AMEC Project 32430 REPORT ISSUE FORM Client Name Electricity Alliance West Project Name Stalybridge – Woodhead (4ZO) OHL Report Title Level 1 Archaeological and Cultural Heritage Appraisal Document Status & Draft Issue No. 1 Issue No. Issue Date 5 October 2012 Author Robert Johns 24 September 2012 Reviewer Ken Whittaker 28 September 2012 Programme Manager Approval Neil Wright 3 October 2012 Copyright and Non-Disclosure Notice The contents and layout of this report are subject to copyright owned by AMEC (©AMEC Environment & Infrastructure UK Limited 2012) save to the extent that copyright has been legally assigned by us to another party or is used by AMEC under licence. To the extent that we own the copyright in this report, it may not be copied or used without our prior written agreement for any purpose other than the purpose indicated in this report. -

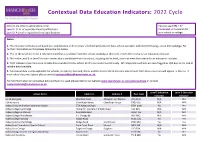

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

The Archaeology of Mining and Quarrying in England a Research Framework

The Archaeology of Mining and Quarrying in England A Research Framework Resource Assessment and Research Agenda The Archaeology of Mining and Quarrying in England A Research Framework for the Archaeology of the Extractive Industries in England Resource Assessment and Research Agenda Collated and edited by Phil Newman Contributors Peter Claughton, Mike Gill, Peter Jackson, Phil Newman, Adam Russell, Mike Shaw, Ian Thomas, Simon Timberlake, Dave Williams and Lynn Willies Geological introduction by Tim Colman and Joseph Mankelow Additional material provided by John Barnatt, Sallie Bassham, Lee Bray, Colin Bristow, David Cranstone, Adam Sharpe, Peter Topping, Geoff Warrington, Robert Waterhouse National Association of Mining History Organisations 2016 Published by The National Association of Mining History Organisations (NAMHO) c/o Peak District Mining Museum The Pavilion Matlock Bath Derbyshire DE4 3NR © National Association of Mining History Organisations, 2016 in association with Historic England The Engine House Fire Fly Avenue Swindon SN2 2EH ISBN: 978-1-871827-41-5 Front Cover: Coniston Mine, Cumbria. General view of upper workings. Peter Williams, NMR DPO 55755; © Historic England Rear Cover: Aerial view of Foggintor Quarry, Dartmoor, Devon. Damian Grady, NMR 24532/004; © Historic England Engine house at Clintsfield Colliery, Lancashire. © Ian Castledine Headstock and surviving buildings at Grove Rake Mine, Rookhope Valley, County Durham. © Peter Claughton Marrick ore hearth lead smelt mill, North Yorkshire © Ian Thomas Grooved stone -

Bullshead V2

THREE WALKS FROM THE BULLS HEAD Tintwistle, Derbyshire Arnfield & Swallow’s Wood 3 miles: Easy A leisurely reservoir and woodland stroll, visiting a local nature reserve. THE BULLS HEAD OPENING HOURS The Longdendale Chain Closed Mondays except Bank Holidays 2, 3¾ or 5½ miles: Easy 78 Old Road, Tintwistle, Mostly level walking around one, two or three of Glossop, Derbyshire SK13 1JY Tuesday to Thursday: 5pm the reservoirs of the Longdendale valley. Tel: 01457 853365 Friday to Sunday, Bank Holidays: 12 noon Website: www.bullsheadpubtintwistle.co.uk Email: [email protected] We serve home-cooked traditional pub food Crowden via Lad’s Leap Friday and Saturday: 12–8.45pm Check us out on TripAdvisor under 8¾ miles: Strenuous Sunday and Bank Holidays: 12–4.45pm A demanding moorland walk with superb views, Glossop or Tintwistle Restaurants Tuesday to Thursday: 5–8.45pm followed by an easy and level return. the right when it meets a stream and swings uphill and away from the map). 10 Walk past the first stile then, just before the stream, leave Arnfield and Swallow’s Wood reservoir. 8 When you reach a narrow lane, turn left (the Longdendale the fence on a path to the left that shortly crosses over and then heads 3 miles: Easy Trail, a disused railway line, is a short distance beyond the road). half-right obliquely up the slope towards the end of a low rocky ridge 9 Walk through Deepclough Farm and follow the lane to Rhodeswood on the skyline. 11 This path skirts round the rocky shoulder above Allow 2 hours. -

Bulls Head, Tintwistle

THREE WALKS FROM THE BULLS HEAD Tintwistle, Derbyshire Arnfield & Swallow’s Wood 3 miles: Easy A leisurely reservoir and woodland stroll, visiting a local nature reserve. THE BULLS HEAD OPENING HOURS The Longdendale Chain Closed Mondays except Bank Holidays 2, 3¾ or 5½ miles: Easy 78 Old Road, Tintwistle, Mostly level walking around one, two or three of Glossop, Derbyshire SK13 1JY Tuesday to Thursday: 5pm the reservoirs of the Longdendale valley. Tel: 01457 853365 Friday to Sunday, Bank Holidays: 12 noon Website: www.bullsheadpubtintwistle.co.uk Email: [email protected] We serve home-cooked traditional pub food Crowden via Lad’s Leap Friday and Saturday: 12–8.45pm Check us out on TripAdvisor under 8¾ miles: Strenuous Sunday and Bank Holidays: 12–4.45pm A demanding moorland walk with superb views, Glossop or Tintwistle Restaurants Tuesday to Thursday: 5–8.45pm followed by an easy and level return. the right when it meets a stream and swings uphill and away from the map). 10 Walk past the first stile then, just before the stream, leave Arnfield and Swallow’s Wood reservoir. 8 When you reach a narrow lane, turn left (the Longdendale the fence on a path to the left that shortly crosses over and then heads 3 miles: Easy Trail, a disused railway line, is a short distance beyond the road). half-right obliquely up the slope towards the end of a low rocky ridge 9 Walk through Deepclough Farm and follow the lane to Rhodeswood on the skyline. 11 This path skirts round the rocky shoulder above Allow 2 hours. -

Journal of the Derbyshire Archaeological and Natural History

J^o. VOL. XX. 1898. OURNAL OF THE .Irchjeologicjil AND Natural History OCI£TY. FBZNTISD POB. THE SOCIETY BY BEMB.OSE & SONS, IiZMITED, 23, OLD BAILEY, LONDON; AND DERBY. ^ JOURNAL OF THE 2)ei*b^8bice Hrcba^olOGical AND NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY EMIT FT) RV RE\^ CHARLES KERRY Keelor of Upper Stoiitiov Be./s. VOL. XX JANUARY 1898 Printed jor the Societv bv BEMROSE .V SONS LTD. 23' OLD B\n.EY LONDON AND DERBY CONTENTS. PAGE List of Officeks v Rules ^''i List of MEMiisiKs " Secretary's Report xvii Balance Sheet xxii Agreement of the Freeholders in Eyam to ihe Award for DIVIDING Eyam Pasture, i2th November, 1702. Contributed by Chas. E. B. Bowles . - - i A FEW BRIEF notes OX SOME RECTORS AND ViCAKS OF HeANOK, CO. Derby. 12 By the Rev. R. J. Burton Will of Elizabeth FitzHerbert, Widow of Ralph Fiiz- Herbert, Esq., of Norbury, Derbyshire, Dated 20th October, 1490. CONIKIBUTED BY ReV. REGINALD H. C. FITZHERBERT - 32 The Ancient Painted Window, Hault Hucknall Church. By the Rev. C. Kerry 40 The Court Rolls of the Manor of Holmesfield, co. Derby, with no IKS BY THE EDITOR 52 ILLUSTRATIONS. Seven Plates of the Painted Window ai Hault Hucknall Church. : : LIST OF OFFICERS THE DUKE OF RUTLAND, K. G. of York. The Most Reverend The Lord Archbishop W. M. Jervis. Duke of Norfolk, K.G., E.M. Hon. Frederick Strutt. Duke of Devonshire, K.G. Hon. Right Rev. Bishop Abraham. Duke of Portland. Right Rev. The Bishop of Lord Scarsdale. Derby. Lord Vernon. Wilmot, Bart., V.C, Lord Waterpark. -

AIA News 140 Spring 2007

INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLOGY 184 SPRING NEWS 2018 THE BULLETIN OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLOGY FREE TO MEMBERS OF AIA Civil Engineering G David Crossley G Power Stations Grain Storage G Restoration projects The revised AIA Programme for 2018 To simplify administrative arrangements the AIA Council have decided that it would be preferable to develop the AIA Members’ Weekend arranged for September in Nottingham into the annual AIA Conference and to provide an additional programme of visits extending the meeting to Wednesday 5 INDUSTRIAL September. The AIA will be supporting the Conference in Caithness (Friday 22 June until Wednesday 27 June) ARCHAEOLOGY which will be run by the AIA affiliated Scottish Industrial Heritage Society, with the Scottish Vernacular Buildings Working Group and Historic Environment Scotland who will deliver the commitments to local NEWS 184 groups and those who have booked travel and accommodation. The programme has been subject to Spring 2018 some revisions: the excursion to Orkney has had to be arranged to take place on Sunday 24 June to avoid clashing with giant cruise ships. The talk by Geoffrey Stell will be on Saturday. Full details and a Honorary President booking form for this event are enclosed. Prof Marilyn Palmer 63 Sycamore Drive, Groby, Leicester LE6 0EW The research seminar organised for Friday 31 August will be held at Nottingham, as planned, on Chairman the subject of – ‘Steaming Ahead: Researching Industrial Archaeology and Heritage in the 21st Dr Michael Nevell Century’. On Sunday morning there will be the AGM followed by the Rolt Lecture when Geoffrey Stell Centre for Applied Archaeology, LG19 Peel Building, will be speaking on ‘Science and Engineering at War: Scapa Flow, 1939-45’. -

Journal of the Derbyshire Archaeological and Natural History Society

g.zo. : v*. /C<-2-. 24FEB.1915 &S-fy VOL. I. 1879. JOURNAL ^^ OF THE Srchjeologicsl AND Natural History OCIfiTY. LONDON BEMROSE & SONS, 10, PATERNOSTER BUILDINGS; AND DERBY. 209 DERBYSHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL and Natural History SOCIETY, Journal of the, complet ' om its beginning in 1879 to 1S83, with numerous vlates (some coloured), cuts of arms, fss., etc., 5 vols. 8vo. sewn, uncut (scarce), £1. 2/6tf 1879-83 : JOURNAL DERBYSHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL X NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY. JANUARY, 1879. LONDON BEMROSE AND SONS, 10, PATERNOSTER BUILWNGS AND DERBY. CONTENTS. List of Officers v Rules - vii List of Members x Secretary's Report xvii Inscription on the Font at Chelmokton. By C. S. Greaves, Q.C., M.A. I Paleolithic Man at Cresvvell. By Rev. J. Magexs Mello, M.A., F.G.S. - - - 15 Incised Slabs in Croxall Church. Drawn by Mary Ussher 25 The Registers, and Churchwardens' and Constables' Accounts of the Parish of Repton. By J. Charles Cox 27 An Account of the Ring of Bells now in the Tower of the Church of All Saints, Derby. By \V. H. St. John Hope 42 A List of the "Alehouses, Innes, and Tavernes" in Derbyshire, in the Year 1577. By \V. H. Hart, F.S.A. 68 Notes on the Registers of Morley and Smalley. By Rev. Charles Kerry 81 Notes on some Old Houses of Derby. By George Bailey - - 92 Notes on Newton Solney Church. By F. J. Robinson 97 Ox the Recent Excavations on the Site of Dale Abbey. By YV. H. St. John Hope 100 The " Mortuary Chapels " of Lichfield Cathedral. -

Longdendale Drought Permit Notice

UNITED UTILITIES WATER LIMITED NOTICE OF APPLICATION FOR A DROUGHT PERMIT TAKE NOTICE that due to the threat of a serious water shortage in the part of its water supply area served by abstractions at Woodhead, Torside and Rhodeswood from the Longdendale chain of reservoirs (together the “Longdendale Reservoirs”) caused by an exceptional shortage of rain, United Utilities Water Limited (the “Company") is applying to the Environment Agency for a drought permit under Section 79A of the Water Resources Act 1991. The proposed drought permit, which is intended to apply for 6 months, will allow the Company to reduce the compensation flow from 45.5 Ml/d to 22.5 Ml/d from Bottoms Lodge Reservoir (a reservoir in Longdendale) to the River Etherow. A reduced flow to the River Etherow will result in more water being retained in Bottoms Lodge Reservoir. This will help to conserve the water available for abstraction from the Longdendale Reservoirs and guarantee a minimum compensation flow to the River Etherow. The permit would expedite a return to normal water levels in Bottoms Lodge Reservoir. In consultation with the Environment Agency and other bodies, including Natural England, the Company has carried out comprehensive environmental assessments into the potential impact of the proposed permit. Anyone may inspect the proposals, free of charge, during normal working hours at:- • Environment Agency, Richard Fairclough House, Knutsford Road, Latchford, Warrington, Cheshire, WA4 1HT. 03708 506 506. • United Utilities Water Limited, Haweswater House, Lingley Mere Business Park, Lingley Green Avenue, Great Sankey, Warrington, WA5 3LP. 01925 679800. • Glossop public library, Talbot Street, Glossop, Derbyshire, SK13 7DG. -

Bridge Mills, Tintwistle, Derbyshire

BRIDGE MILLS, TINTWISTLE, DERBYSHIRE 14/12/2016 FLOOD RISK ASSESSMENT The Alan Johnston Partnership LLP Ref: 216-232 216216----232232 Bridge Mills, Tintwistle, Derbyshire Prepared By Document Owner(s) Project/Organization Role Kenny O’Brien Partner John Speers Civil Engineer Project Closure Report Version Control Version Date Author Change Description P1 09/12/2016 J.Speers First Issue P2 14/12/2016 J.Speers Minor Amendments Record of Approval Originator Approved Date J.Speers K.O’Brien 09/12/2016 J.Speers K.O’Brien 14/12/2016 ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- Page 1 216216----232232 Bridge Mills, Tintwistle, Derbyshire Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 444 2.0 SITE DESCRIPTIODESCRIPTIONNNN .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 555 2.1 Geology ............................................................................................... 5 2.2 Hydrogeology ...................................................................................... 6 2.3 Hydrology ............................................................................................ 6 3.0 PROPOSED DEVELODEVELOPMENTPMENT ...........................................................................................................................................................................