Price Dynamics in the Belarusian Black Market for Foreign Exchange☆

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

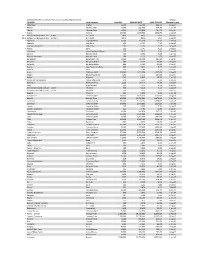

Maximum Monthly Stipend Rates For

MAXIMUM MONTHLY STIPEND RATES FOR FELLOWS AND SCHOLARS Jul 2020 COUNTRY Local Currency Local DSA MAX RES RATE MAX TRV RATE Effective % date * Afghanistan Afghani 12,600 132,300 198,450 1-Aug-07 * Albania Albania Lek(e) 14,000 220,500 330,750 1-Jan-05 Algeria Algerian Dinar 31,600 331,800 497,700 1-Aug-07 * Angola Kwanza 133,000 1,396,500 2,094,750 1-Aug-07 #N/A Antigua and Barbuda (1 Apr. - 30 Nov.) E.C. Dollar #N/A #N/A #N/A 1-Aug-07 #N/A Antigua and Barbuda (1 Dec. - 31 Mar.) E.C. Dollar #N/A #N/A #N/A 1-Aug-07 * Argentina Argentine Peso 18,600 153,450 230,175 1-Jan-05 Australia AUL Dollar 453 4,757 7,135 1-Aug-07 Australia - Academic AUL Dollar 453 1,200 7,135 1-Aug-07 * Austria Euro 261 2,741 4,111 1-Aug-07 * Azerbaijan (new)Azerbaijan Manat 239 1,613 2,420 1-Jan-05 Bahrain Bahraini Dinar 106 2,226 3,180 1-Jan-05 Bahrain - Academic Bahraini Dinar 106 1,113 1,670 1-Aug-07 Bangladesh Bangladesh Taka 12,400 130,200 195,300 1-Aug-07 Barbados Barbados Dollar 880 9,240 13,860 1-Aug-07 Barbados Barbados Dollar 880 9,240 13,860 1-Aug-07 * Belarus New Belarusian Ruble 600 5,850 8,775 1-Jan-06 Belgium Euro 338 3,549 5,324 1-Aug-07 Benin CFA Franc(XOF) 123,000 1,291,500 1,937,250 1-Aug-07 Bhutan Bhutan Ngultrum 7,290 76,545 114,818 1-Aug-07 * Bolivia Boliviano 1,200 10,800 16,200 1-Jan-07 * Bosnia and Herzegovina Convertible Mark 279 3,557 5,336 1-Jan-05 Botswana Botswana Pula 2,220 23,310 34,965 1-Aug-07 Brazil Brazilian Real 530 4,373 6,559 1-Jan-05 British Virgin Islands (16 Apr. -

The Monetary Legacy of the Soviet Union / Patrick Conway

ESSAYS IN INTERNATIONAL FINANCE ESSAYS IN INTERNATIONAL FINANCE are published by the International Finance Section of the Department of Economics of Princeton University. The Section sponsors this series of publications, but the opinions expressed are those of the authors. The Section welcomes the submission of manuscripts for publication in this and its other series. Please see the Notice to Contributors at the back of this Essay. The author of this Essay, Patrick Conway, is Professor of Economics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He has written extensively on the subject of structural adjustment in developing and transitional economies, beginning with Economic Shocks and Structural Adjustment: Turkey after 1973 (1987) and continuing, most recently, with “An Atheoretic Evaluation of Success in Structural Adjustment” (1994a). Professor Conway has considerable experience with the economies of the former Soviet Union and has made research visits to each of the republics discussed in this Essay. PETER B. KENEN, Director International Finance Section INTERNATIONAL FINANCE SECTION EDITORIAL STAFF Peter B. Kenen, Director Margaret B. Riccardi, Editor Lillian Spais, Editorial Aide Lalitha H. Chandra, Subscriptions and Orders Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conway, Patrick J. Currency proliferation: the monetary legacy of the Soviet Union / Patrick Conway. p. cm. — (Essays in international finance, ISSN 0071-142X ; no. 197) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-88165-104-4 (pbk.) : $8.00 1. Currency question—Former Soviet republics. 2. Monetary policy—Former Soviet republics. 3. Finance—Former Soviet republics. I. Title. II. Series. HG136.P7 no. 197 [HG1075] 332′.042 s—dc20 [332.4′947] 95-18713 CIP Copyright © 1995 by International Finance Section, Department of Economics, Princeton University. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

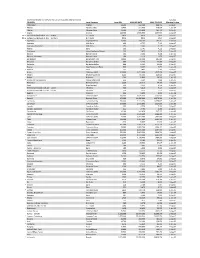

Maximum Monthly Stipend Rates for Fellows And

MAXIMUM MONTHLY STIPEND RATES FOR FELLOWS AND SCHOLARS Sep 2020 COUNTRY Local Currency Local DSA MAX RES RATE MAX TRV RATE Effective % date Afghanistan Afghani 12,500 131,250 196,875 1-Aug-07 * Albania Albania Lek(e) 13,100 206,325 309,488 1-Jan-05 Algeria Algerian Dinar 31,600 331,800 497,700 1-Aug-07 * Angola Kwanza 134,000 1,407,000 2,110,500 1-Aug-07 #N/A Antigua and Barbuda (1 Apr. - 30 Nov.) E.C. Dollar #N/A #N/A #N/A 1-Aug-07 #N/A Antigua and Barbuda (1 Dec. - 31 Mar.) E.C. Dollar #N/A #N/A #N/A 1-Aug-07 * Argentina Argentine Peso 19,700 162,525 243,788 1-Jan-05 Australia AUL Dollar 453 4,757 7,135 1-Aug-07 Australia - Academic AUL Dollar 453 1,200 7,135 1-Aug-07 Austria Euro 261 2,741 4,111 1-Aug-07 Azerbaijan (new)Azerbaijan Manat 239 1,613 2,420 1-Jan-05 Bahrain Bahraini Dinar 106 2,226 3,180 1-Jan-05 Bahrain - Academic Bahraini Dinar 106 1,113 1,670 1-Aug-07 Bangladesh Bangladesh Taka 12,400 130,200 195,300 1-Aug-07 Barbados Barbados Dollar 880 9,240 13,860 1-Aug-07 Barbados Barbados Dollar 880 9,240 13,860 1-Aug-07 * Belarus New Belarusian Ruble 680 6,630 9,945 1-Jan-06 Belgium Euro 338 3,549 5,324 1-Aug-07 Benin CFA Franc(XOF) 123,000 1,291,500 1,937,250 1-Aug-07 Bhutan Bhutan Ngultrum 7,290 76,545 114,818 1-Aug-07 Bolivia Boliviano 1,180 10,620 15,930 1-Jan-07 * Bosnia and Herzegovina Convertible Mark 264 3,366 5,049 1-Jan-05 Botswana Botswana Pula 2,220 23,310 34,965 1-Aug-07 Brazil Brazilian Real 530 4,373 6,559 1-Jan-05 British Virgin Islands (16 Apr. -

Banking Sector and Economy of CEE Countries: Development Features and Correlation

Centre for Research on Settlements and Urbanism Journal of Settlements and Spatial Planning J o u r n a l h o m e p a g e: http://jssp.reviste.ubbcluj.ro Banking Sector and Economy of CEE Countries: Development Features and Correlation Iurii UMANTSIV 1, Olena ISHCHENKO 1 1 Kyiv National University of Trade and Economics, Faculty of Economics, Management and Psychology, Department of Economic Theory and Competition Policy, Kyiv, UKRAINE E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] DOI: 10.24193/JSSP.2017.1.05 https://doi.org/10.24193/JSSP.2017.1.05 K e y w o r d s: economy of CEE country, banking system, financial sector, role of banks, correlation between GDP and bank investments, EU operational programs, CEE countries, banking sector development A B S T R A C T This research focuses on the analysis of current trends in the banking sector of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), and on its role in the development of the economy. This region is represented by countries situated at different levels of development and types of economic system. The following countries are analyzed: Bulgaria, Poland, Romania, the Republic of Belarus and Ukraine. The article starts with a general description of the economy of each of the five countries listed above, followed by a discussion of main trends of their development and a comparison of these states based on the status of their socioeconomic development. The study will also examine the banking systems of each of these countries looking at the types of banks that are present on the market, capital ownership, and market share, as well as the main indicators of soundness of the banking system. -

Use of National Currencies in International Settlements

JOINT RESEARCH PAPER USE OF NATIONAL CURRENCIES IN INTERNATIONAL SETTLEMENTS. EXPERIENCE OF THE BRICS COUNTRIES Moscow RISS 2017 USE OF NATIONAL CURRENCIES IN INTERNATIONAL SETTLEMENTS. EXPERIENCE OF THE BRICS COUNTRIES Authors Uallace Moreira Lima (Federal University of Bahia); Marcelo Xavier do Nascimento (Federal University of Pernambuco); Sergey Karataev, Nikolay Troshin, Pavel Zakharov, Natalya Gribova, Ivan Bazhenov (Russian Institute for Strategic Studies); Shekhar Hari Kumar, Ila Patnaik (National Institute of Public Finance and Policy); Liu Dongmin, Xiao Lisheng, Lu Ting, Xiong Aizong, Zhang Chi (Institute of World Economics and Politics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences); Ronney Ncwadi (Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University); Jaya Josie (Human Sciences Research Council) Editors Sergey Karataev, Nikolay Troshin, Ivan Bazhenov, Jaya Josie Design and Publication Oleg Strizhak, Olga Farenkova (Russian Institute for Strategic Studies) Abstract Financial crises of the past decades revealed the instability of the modern international monetary system based on a single dominant currency. Increasing the role and turnover of national currencies in international economic transactions and payments would contribute to redressing the existing imbalance. BRICS countries’ experience indicates that effi cient currency internationalization can be reached by both forming a number of prerequisites and fi nancial and economic policies pursued by the authorities. Strengthening the BRICS countries’ collaboration and implementation of joint initiatives should help create favorable conditions for promoting a wider use of their currencies in international settlements. Keywords BRICS – Currency internationalization – Emerging markets – International monetary system – International settlements Th e views expressed in this survey are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Russian Institute for Strategic Studies. -

Culture and Change in Belarus

East European Reflection Group (EE RG) Identifying Cultural Actors of Change in Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova Culture and Change in Belarus Report prepared by Yael Ohana, Rapporteur Generale Bratislava, August 2007 Culture and Change in Belarus “Life begins for the counter-culture in Belarus after regime change”. Anonymous, at the consultation meeting in Kiev, Ukraine, June 14 2007. Introduction1 Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine have recently become direct neighbours of the European Union. Both Moldova and Ukraine have also become closer partners of the European Union through the European Neighbourhood Policy. Neighbourhood usually refers to people next-door, people we know, or could easily get to know. It implies interest, curiosity and solidarity in the other living close by. For the moment, the European Union’s “neighbourhood” is something of an abstract notion, lacking in substance. In order to avoid ending up “lost in translation”, it is necessary to question and some of the basic premises on which cultural and other forms of European cooperation are posited. In an effort to create constructive dialogue with this little known neighbourhood, the European Cultural Foundation (ECF) and the German Marshall Fund of the United States (GMF) are currently preparing a three- year partnership to support cultural agents of change in Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine. In the broad sense, this programme is to work with, and provide assistance to, initiatives and institutions that employ creative, artistic and cultural means to contribute to the process of constructive change in each of the three countries. ECF and GMF have begun a process of reflection in order to understand the extent to which the culture sphere in each of the three countries under consideration can support change, defined here as processes and dynamics contributing to democratisation, Europeanisation and modernisation in the three countries concerned. -

Maximum Monthly Stipend Rates For

MAXIMUM MONTHLY STIPEND RATES FOR FELLOWS AND SCHOLARS Mar 2021 COUNTRY Local Currency Local DSA MAX RES RATE MAX TRV RATE Effective % date Afghanistan Afghani 12,600 132,300 198,450 1-Aug-07 * Albania Albania Lek(e) 13,400 211,050 316,575 1-Jan-05 Algeria Algerian Dinar 31,600 331,800 497,700 1-Aug-07 * Angola Kwanza 146,000 1,533,000 2,299,500 1-Aug-07 #N/A Antigua and Barbuda (1 Apr. - 30 Nov.) E.C. Dollar #N/A #N/A #N/A 1-Aug-07 #N/A Antigua and Barbuda (1 Dec. - 31 Mar.) E.C. Dollar #N/A #N/A #N/A 1-Aug-07 * Argentina Argentine Peso 23,900 197,175 295,763 1-Jan-05 Australia AUL Dollar 453 4,757 7,135 1-Aug-07 Australia - Academic AUL Dollar 453 1,200 7,135 1-Aug-07 Austria Euro 261 2,741 4,111 1-Aug-07 * Azerbaijan (new)Azerbaijan Manat 240 1,620 2,430 1-Jan-05 Bahrain Bahraini Dinar 106 2,226 3,180 1-Jan-05 Bahrain - Academic Bahraini Dinar 106 1,113 1,670 1-Aug-07 Bangladesh Bangladesh Taka 12,400 130,200 195,300 1-Aug-07 Barbados Barbados Dollar 880 9,240 13,860 1-Aug-07 Barbados Barbados Dollar 880 9,240 13,860 1-Aug-07 Belarus New Belarusian Ruble 660 6,435 9,653 1-Jan-06 * Belgium Euro 333 3,497 5,245 1-Aug-07 Benin CFA Franc(XOF) 123,000 1,291,500 1,937,250 1-Aug-07 * Bhutan Bhutan Ngultrum 8,200 86,100 129,150 1-Aug-07 * Bolivia Boliviano 1,200 10,800 16,200 1-Jan-07 * Bosnia and Herzegovina Convertible Mark 256 3,264 4,896 1-Jan-05 Botswana Botswana Pula 2,220 23,310 34,965 1-Aug-07 Brazil Brazilian Real 530 4,373 6,559 1-Jan-05 British Virgin Islands (16 Apr. -

The Impact of Deregulating OBU's Renminbi's Business on The

The Impact of Deregulating OBU’s Renminbi’s Business on the Financing Behavior of Taiwanese Businessmen in China Yi Chun Kuo, Associate professor of Chung Yuan Christian University, Taiwan ABSTRACT August 2011, Taiwan Financial Supervisory Commission (FSC) announced that banks in Taiwan can serve the Renmibi’s (RMB) business on offshore banking unit (OBU). After that, Taiwanese businessmen can engage in RMB-related businesses through OBU in Taiwan to get access to RMB financing to enhance the flexibility in capital utilization. The foreign direct investment (FDI) and international trade of Taiwanese businessmen in China are important parts of Taiwan’s economy, which create huge amount of cash flow between the Mainland China and Taiwan. Due to the financial crisis in 2008, the fluctuation of exchange rate caused serious problems to import and export enterprises. RMB is relatively stable than other currencies and being preferred by Taiwanese businesses for their financial risk controlling. This study survey the policy impact of the deregulation and aims to find out whether the OBU business opening would affect Taiwanese businessmen in terms of their financing behaviors, and whether the opening of OBU business is beneficial to most Taiwanese businessmen or only on some Taiwanese businessmen. Keywords: Financial behavior, Offshore banking unit (OBU), Renminibi (RMB), Taiwanese businessmen in China, Cross-border trade settlement, Cross-border RMB Business INTRODUCTION China has been implementing the reform and opening up policies since 1978. With the economic development and rise of China, China has become the world’s second largest economy by 2010. According to the Chinese customs statistics, China’s exports in January 1992 amounted to 3,991 million USD and increased to 113,653.43 million USD in 2009. -

List of Currencies of All Countries

The CSS Point List Of Currencies Of All Countries Country Currency ISO-4217 A Afghanistan Afghan afghani AFN Albania Albanian lek ALL Algeria Algerian dinar DZD Andorra European euro EUR Angola Angolan kwanza AOA Anguilla East Caribbean dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar XCD Argentina Argentine peso ARS Armenia Armenian dram AMD Aruba Aruban florin AWG Australia Australian dollar AUD Austria European euro EUR Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN B Bahamas Bahamian dollar BSD Bahrain Bahraini dinar BHD Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka BDT Barbados Barbadian dollar BBD Belarus Belarusian ruble BYR Belgium European euro EUR Belize Belize dollar BZD Benin West African CFA franc XOF Bhutan Bhutanese ngultrum BTN Bolivia Bolivian boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina konvertibilna marka BAM Botswana Botswana pula BWP 1 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Brazil Brazilian real BRL Brunei Brunei dollar BND Bulgaria Bulgarian lev BGN Burkina Faso West African CFA franc XOF Burundi Burundi franc BIF C Cambodia Cambodian riel KHR Cameroon Central African CFA franc XAF Canada Canadian dollar CAD Cape Verde Cape Verdean escudo CVE Cayman Islands Cayman Islands dollar KYD Central African Republic Central African CFA franc XAF Chad Central African CFA franc XAF Chile Chilean peso CLP China Chinese renminbi CNY Colombia Colombian peso COP Comoros Comorian franc KMF Congo Central African CFA franc XAF Congo, Democratic Republic Congolese franc CDF Costa Rica Costa Rican colon CRC Côte d'Ivoire West African CFA franc XOF Croatia Croatian kuna HRK Cuba Cuban peso CUC Cyprus European euro EUR Czech Republic Czech koruna CZK D Denmark Danish krone DKK Djibouti Djiboutian franc DJF Dominica East Caribbean dollar XCD 2 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Dominican Republic Dominican peso DOP E East Timor uses the U.S. -

A Case Study of a Currency Crisis: the Russian Default of 1998

agents attempting to alter their portfolio by buying A Case Study of a another currency with the currency of country A.2 This might occur because investors fear that the Currency Crisis: The government will finance its high prospective deficit through seigniorage (printing money) or attempt to Russian Default of 1998 reduce its nonindexed debt (debt indexed to neither another currency nor inflation) through devaluation. Abbigail J. Chiodo and Michael T. Owyang A devaluation occurs when there is market pres- sure to increase the exchange rate (as measured by currency crisis can be defined as a specula- domestic currency over foreign currency) because tive attack on a country’s currency that can the country either cannot or will not bear the cost A result in a forced devaluation and possible of supporting its currency. In order to maintain a debt default. One example of a currency crisis lower exchange rate peg, the central bank must buy occurred in Russia in 1998 and led to the devaluation up its currency with foreign reserves. If the central of the ruble and the default on public and private bank’s foreign reserves are depleted, the government debt.1 Currency crises such as Russia’s are often must allow the exchange rate to float up—a devalu- thought to emerge from a variety of economic condi- ation of the currency. This causes domestic goods tions, such as large deficits and low foreign reserves. and services to become cheaper relative to foreign They sometimes appear to be triggered by similar goods and services. The devaluation associated with crises nearby, although the spillover from these con- a successful speculative attack can cause a decrease tagious crises does not infect all neighboring econ- in output, possible inflation, and a disruption in omies—only those vulnerable to a crisis themselves. -

Belarus Country Report BTI 2016

BTI 2016 | Belarus Country Report Status Index 1-10 4.27 # 99 of 129 Political Transformation 1-10 3.93 # 91 of 129 Economic Transformation 1-10 4.61 # 90 of 129 Management Index 1-10 3.02 # 115 of 129 scale score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2016. It covers the period from 1 February 2013 to 31 January 2015. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2016 — Belarus Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2016. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. BTI 2016 | Belarus 2 Key Indicators Population M 9.5 HDI 0.786 GDP p.c., PPP $ 18184.9 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 0.0 HDI rank of 187 53 Gini Index 26.0 Life expectancy years 72.5 UN Education Index 0.820 Poverty3 % 0.0 Urban population % 76.3 Gender inequality2 0.152 Aid per capita $ 11.1 Sources (as of October 2015): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2015 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2014. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.10 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary Summer 2014 marked the 20th anniversary of Aliaksandr Lukashenka’s election as the first, and so far only, president of the Republic of Belarus.