WAVES of PEOPLE Exploring the Movements and Patterns of Migration That Have Shaped Parramatta Through Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Convict Labour and Colonial Society in the Campbell Town Police District: 1820-1839

Convict Labour and Colonial Society in the Campbell Town Police District: 1820-1839. Margaret C. Dillon B.A. (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph. D.) University of Tasmania April 2008 I confirm that this thesis is entirely my own work and contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis. Margaret C. Dillon. -ii- This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Margaret C. Dillon -iii- Abstract This thesis examines the lives of the convict workers who constituted the primary work force in the Campbell Town district in Van Diemen’s Land during the assignment period but focuses particularly on the 1830s. Over 1000 assigned men and women, ganged government convicts, convict police and ticket holders became the district’s unfree working class. Although studies have been completed on each of the groups separately, especially female convicts and ganged convicts, no holistic studies have investigated how convicts were integrated into a district as its multi-layered working class and the ways this affected their working and leisure lives and their interactions with their employers. Research has paid particular attention to the Lower Court records for 1835 to extract both quantitative data about the management of different groups of convicts, and also to provide more specific narratives about aspects of their work and leisure. -

Greater Parramatta and the Olympic Peninsula Is the the Way We All Imagine Greater Sydney

Greater Our true centre: the connected, Parramatta and the unifying heart GPOP Olympic Peninsula About Us The Greater Sydney Commission (the Commission) was established by the NSW Government to lead metropolitan planning for Greater Sydney. This means the Commission plays a co-ordinating role in economic, social and environmental planning across the whole of Greater Sydney. The Commission has specific roles and responsibilities, such as producing District Plans, the Metropolitan Strategy and identifying infrastructure priorities. Collaboration and engagement are at the core of everything the Commission does. We work across government, with communities, interest groups, institutions, business and investors to ensure that planning for Greater Sydney results in a productive, liveable and sustainable future city. October 2016 FOREWORD CHIEF COMMISSIONER’S DISTRICT COMMISSIONER’S FOREWORD FOREWORD It’s time for a change of perspective and a change in Greater Parramatta and the Olympic Peninsula is the the way we all imagine Greater Sydney. geographic and demographic heart of Greater Sydney, Today, more than 2 million people live west of Sydney and a key part of the West Central District. Olympic Park, yet everyday around 300,000 people We have the opportunity to shape the transformation leave the region to travel for work. of the place we now call GPOP. Greater Sydney needs a true city at its centre, close Global best practice shows that a co-ordinated to its heart. We need a central ‘30-minute city’, that is approach to public and private investment is critical connected to the north, south, east and west. for successful transformation, involving innovation and GPOP is the name we have given to the Greater enterprise. -

Indigenous Community Protocols for Bankstown Area Multicultural Network

INDIGENOUS COMMUNITY PROTOCOLS FOR BAMN MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE Practical protocols for working with the Indigenous Community of South West Sydney 1 Contents RESPECT, ACKNOWLEDGE, LISTEN Practical protocols for working with Indigenous communities in Western Sydney What are protocols? 1. Get To Know Your Indigenous Community Identity Diversity – Different rules for different community groups (there can sometimes be different groups within communities) 2. Consult Indigenous Reference Groups, Steering Committees and Boards 3. Get Permission The Local Community Elders Traditional Owners Ownership Copyright and Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property 4. Communicate Language Koori Time Report back and stay in touch 5. Ethics and Morals Confidentiality Integrity and trust 6. Correct Procedures Respect What to call people Traditional Welcome or Welcome to Country Acknowledging Traditional Owners Paying People Indigenous involvement Cross Cultural Training 7. Indigenous Organisations and Western Sydney contacts Major Indigenous Organisations Local Aboriginal Land Councils Indigenous Corporations/Community Organisations Indigenous Council, Community and Arts workers 8. Keywords to Remember 9. Other Protocol Resource Documents 2 What Are Protocols? Protocols can be classified as a set of rules, regulations, processes, procedures, strategies, or guidelines. Protocols are simply the ways in which you work with people, and communicate and collaborate with them appropriately. They are a guide to assist you with ways in which you can work, communicate and collaborate with the Indigenous community of Western Sydney. A wealth of Indigenous protocols documentation already exists (see Section 9), but to date the practice of following them is not widespread. Protocols are also standards of behaviour, respect and knowledge that need to be adopted. You might even think of them as a code of manners to observe, rather than a set of rules to obey. -

Western Sydney Airport Fast Train – Discussion Paper

Western Sydney Airport Fast 2 March 2016 Train - Discussion Paper Reference: 250187 Parramatta City Council & Sydney Business Chamber - Western Sydney Document control record Document prepared by: Aurecon Australasia Pty Ltd ABN 54 005 139 873 Australia T +61 2 9465 5599 F +61 2 9465 5598 E [email protected] W aurecongroup.com A person using Aurecon documents or data accepts the risk of: a) Using the documents or data in electronic form without requesting and checking them for accuracy against the original hard copy version. b) Using the documents or data for any purpose not agreed to in writing by Aurecon. Disclaimer This report has been prepared by Aurecon at the request of the Client exclusively for the use of the Client. The report is a report scoped in accordance with instructions given by or on behalf of Client. The report may not address issues which would need to be addressed with a third party if that party’s particular circumstances, requirements and experience with such reports were known and may make assumptions about matters of which a third party is not aware. Aurecon therefore does not assume responsibility for the use of, or reliance on, the report by any third party and the use of, or reliance on, the report by any third party is at the risk of that party. Project 250187 DRAFT REPORT: NOT FORMALLY ENDORSED BY PARRAMATTA CITY COUNCIL Parramatta Fast Train Discussion Paper FINAL DRAFT B to Client 2 March.docx 2 March 2016 Western Sydney Airport Fast Train - Discussion Paper Date 2 March 2016 Reference 250187 Aurecon -

Parramatta's Archaeological Landscape

Parramatta’s archaeological landscape Mary Casey Settlement at Parramatta, the third British settlement in Australia after Sydney Cove and Norfolk Island, began with the remaking of the landscape from an Aboriginal place, to a military redoubt and agricultural settlement, and then a township. There has been limited analysis of the development of Parramatta’s landscape from an archaeological perspective and while there have been numerous excavations there has been little exploration of these sites within the context of this evolving landscape. This analysis is important as the beginnings and changes to Parramatta are complex. The layering of the archaeology presents a confusion of possible interpretations which need a firmer historical and landscape framework through which to interpret the findings of individual archaeological sites. It involves a review of the whole range of maps, plans and images, some previously unpublished and unanalysed, within the context of the remaking of Parramatta and its archaeological landscape. The maps and images are explored through the lense of government administration and its intentions and the need to grow crops successfully to sustain the purposes of British Imperialism in the Colony of New South Wales, with its associated needs for successful agriculture, convict accommodation and the eventual development of a free settlement occupied by emancipated convicts and settlers. Parramatta’s river terraces were covered by woodlands dominated by eucalypts, in particular grey box (Eucalyptus moluccana) and forest -

Re-Awakening Languages: Theory and Practice in the Revitalisation Of

RE-AWAKENING LANGUAGES Theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages Edited by John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch and Michael Walsh Copyright Published 2010 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS University of Sydney Library sydney.edu.au/sup © John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch & Michael Walsh 2010 © Individual contributors 2010 © Sydney University Press 2010 Reproduction and Communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library F03 University of Sydney NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Readers are advised that protocols can exist in Indigenous Australian communities against speaking names and displaying images of the deceased. Please check with local Indigenous Elders before using this publication in their communities. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Re-awakening languages: theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages / edited by John Hobson … [et al.] ISBN: 9781920899554 (pbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--Languages--Revival. Australian languages--Social aspects. Language obsolescence--Australia. Language revival--Australia. iv Copyright Language planning--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Hobson, John Robert, 1958- Lowe, Kevin Connolly, 1952- Poetsch, Susan Patricia, 1966- Walsh, Michael James, 1948- Dewey Number: 499.15 Cover image: ‘Wiradjuri Water Symbols 1’, drawing by Lynette Riley. Water symbols represent a foundation requirement for all to be sustainable in their environment. -

Community Update August 2017

Community update August 2017 Changes to bus stops in Rozelle, Lilyfield, Leichhardt, Annandale and Camperdown Transport for NSW has identified some ways to improve bus on-time running in Sydney’s inner west. Transport for NSW and Roads and Maritime Services } Norton Street near Carlisle Street asked the community for feedback between December } Norton Street near Norton Plaza (one removal only) 2015 and January 2016 on a proposal to make changes to some bus stops in Sydney’s inner west. We would like to } Parramatta Road near Mallet Street thank everyone for their comments. } Parramatta Road near Larkin Street We received feedback from 298 people and organisations. We expect to start work at these locations later in 2017 The feedback included comments around access to bus and will notify you before this happens. services, additional walking distances, loss of parking, removing trees on Norton Street and project justification. The detailed maps in this community update explain the final proposal of changes to bus stops. WHAT HAPPENS NEXT? BACKGROUND We summarised the feedback and our responses in a Community Consultation Report which can be viewed at These changes are part of Sydney’s Bus Future, the NSW www.rms.nsw.gov.au/bpp. Government’s plan to redesign Sydney’s bus network to meet customer needs now and into the future. In this plan, We considered all feedback while finalising the proposal our customers tell us that travel time and on-time running and decided not to proceed with changes at the are some of the most important service -

Practical Protocols for Working with the Indigenous Community of Western Sydney

CCD_RAL_bk.qxd 15/7/03 3:04 PM Page 1 CCD_RAL_Final.qxd 15/7/03 3:06 PM Page 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was assisted by the Government of NSW through the and The Federal Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body. Researched and Written by This document is a project of the Angelina Hurley Indigenous Program of Indigenous Program Manager Community Cultural Development New Community Cultural Development NSW South Wales (CCDNSW) Draft Review and Copyright Section by © Community Cultural Development NSW Terri Janke Ltd, 2003 Principle Solicitor Terri Janke and Company Suite 8 54 Moore St. Design and Printing by Liverpool NSW 2170 MLC Powerhouse Design Studio PO Box 512 April 2003 Liverpool RC 1871 Ph: (02) 9821 2210 Cover Art Work Fax: (02) 9821 3460 ‘You Can’t Have Our Spirituality Without Web: www.ccdnsw.org Our Political Reality’ by Indigenous Artist Gordon Hookey Internal Art Work ‘Men’s Ceremony’ by Indigenous Artist Adam Hill CCD_RAL_Final.qxd 15/7/03 5:05 PM Page 2 Contents RESPECT, ACKNOWLEDGE, LISTEN: Practical protocols for working with the Indigenous Community of Western Sydney . .3 Who are Community Cultural Development New South Wales (CCDNSW)? What is ccd? . .3 What Are Protocols? . .3 1. Get To Know Your Indigenous Community . .4 Identity . .5 Diversity - Different Rules For Different Groups . .6 2. Consult . .6 Indigenous Reference Groups, Steering Committees and Boards . .7 3. Get Permission . .8 The Local Community . .8 Elders . .8 Traditional Owners . .8 Ownership . .9 Copyright And Indigenous Cultural And Intellectual Property . .9 4. Communicate . .10 Language . .10 Koori Time . -

13.0 Remaking the Landscape

12 Chapter 13: Remaking the Landscape 13.0 Remaking the landscape 13.1 Research Question The Conservatorium site is located within one of the most significant historic and symbolic landscapes created by European settlers in Australia. The area is located between the sites of the original and replacement Government Houses, on a prominent ridge. While the utility of this ridge was first exploited by a group of windmills, utilitarian purposes soon became secondary to the Macquaries’ grandiose vision for Sydney and the Governor’s Domain in particular. The later creations of the Botanic Gardens, The Garden Palace and the Conservatorium itself, re-used, re-interpreted and created new vistas, paths and planting to reflect the growing urban and economic importance of Sydney within the context of the British empire. Modifications to this site, its topography and vegetation, can therefore be interpreted within the theme of landscape as an expression of the ideology of colonialism. It is considered that this site is uniquely placed to address this research theme which would act as a meaningful interpretive framework for archaeological evidence relating to environmental and landscape features.1 In response to this research question evidence will be presented on how the Government Domain was transformed by the various occupants of First Government House, and the later Government House, during the first years of the colony. The intention behind the gathering and analysis of this evidence is to place the Stables building and the archaeological evidence from all phases of the landscape within a conceptual framework so that we can begin to unravel the meaning behind these major alterations. -

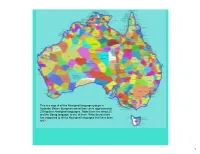

This Is a Map of All the Aboriginal Language Groups in Australia

This is a map of all the Aboriginal language groups in Australia. Before European arrival there were approximately 250 spoken Aboriginal languages. Today there are about 25, and the Darug language is one of them. What do you think has happened to all the Aboriginal languages that have been lost? 1 Do you speak my language? This lesson: Learning to speak some of the Darug language Aunty Val Aurisch Speaking at The Gully Culture Camp 2010 Picture soured 20 April 2011 from: http://www.livingcountry.com.au/gallery.cfm 2 Listen to me speak the Darug language Richard Green helps keep his language alive and strong by teaching it to students at Chifley College, Dunheved Campus and at Doonside Technical High School. Listen to Richard Green talk about his language in Darug (and English) by clicking on the picture of Richard. This will take you to to the William Dawes website where you can listen to an mp3 file. Richard Green Picture: Copyright 2009 The Hills Shire Council 3 Can you speak Darug language? Click the Darug name and drag it to the 'Word' column. Select the check button to find out how you went! Words sourced from Yarramundi Kids website on 20 April 2011: http://yarramundikids.tv/yarramundikids/howdoyousay.html 4 A shared historyA brief introduction to Lieutenant William Dawes Lieutenant William Dawes (1762-1836) was known as an officer of marines, scientist and administrator, yet it is his interest in studying the local Eora (Darug) people that tells the story of a shared history. Dawes developed a friendship with a young Darug girl who was about fifteen years old. -

Commonwealth of Australia

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 Warning This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of The Charles Darwin University with permission from the author(s). Any further reproduction or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander THESAURUS First edition by Heather Moorcroft and Alana Garwood 1996 Acknowledgements ATSILIRN conference delegates for the 1st and 2nd conferences. Alex Byrne, Melissa Jackson, Helen Flanders, Ronald Briggs, Julie Day, Angela Sloan, Cathy Frankland, Andrew Wilson, Loris Williams, Alan Barnes, Jeremy Hodes, Nancy Sailor, Sandra Henderson, Lenore Kennedy, Vera Dunn, Julia Trainor, Rob Curry, Martin Flynn, Dave Thomas, Geraldine Triffitt, Bill Perrett, Michael Christie, Robyn Williams, Sue Stanton, Terry Kessaris, Fay Corbett, Felicity Williams, Michael Cooke, Ely White, Ken Stagg, Pat Torres, Gloria Munkford, Marcia Langton, Joanna Sassoon, Michael Loos, Meryl Cracknell, Maggie Travers, Jacklyn Miller, Andrea McKey, Lynn Shirley, Xalid Abd-ul-Wahid, Pat Brady, Sau Foster, Barbara Lewancamp, Geoff Shepardson, Colleen Pyne, Giles Martin, Herbert Compton Preface Over the past months I have received many queries like "When will the thesaurus be available", or "When can I use it". Well here it is. At last the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Thesaurus, is ready. However, although this edition is ready, I foresee that there will be a need for another and another, because language is fluid and will change over time. As one of the compilers of the thesaurus I am glad it is finally completed and available for use. -

Yurunnhang Bungil Nyumba: Infusing Aboriginal Ways of Being Into Teaching Practice in Australia

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2020 Yurunnhang Bungil Nyumba: Infusing Aboriginal ways of being into teaching practice in Australia Lisa Buxton The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Education Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Buxton, L. (2020). Yurunnhang Bungil Nyumba: Infusing Aboriginal ways of being into teaching practice in Australia (Doctor of Education). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/248 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Yurunnhang Bungil Nyumba: Infusing Aboriginal ways of being into teaching practice in Australia Lisa Maree Buxton MPhil, MA, GDip Secondary Ed, GDip Aboriginal Ed, BA. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Doctor of Education School of Education Sydney Campus January, 2020 Acknowledgement of Country Protocols The protocol for introducing oneself to other Indigenous people is to provide information about one’s cultural location, so that connection can be made on political, cultural and social grounds and relations established. (Moreton-Robinson, 2000, pp. xv) I would like firstly to acknowledge with respect Country itself, as a knowledge holder, and the ancients and ancestors of the country in which this study was conducted, Gadigal, Bidjigal and Dharawal of Eora Country.