2017 • Vol. 1 • No. 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catherine the Great and the Development of a Modern Russian Sovereignty, 1762-1796

Catherine the Great and the Development of a Modern Russian Sovereignty, 1762-1796 By Thomas Lucius Lowish A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Victoria Frede-Montemayor, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor Kinch Hoekstra Spring 2021 Abstract Catherine the Great and the Development of a Modern Russian Sovereignty, 1762-1796 by Thomas Lucius Lowish Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Victoria Frede-Montemayor, Chair Historians of Russian monarchy have avoided the concept of sovereignty, choosing instead to describe how monarchs sought power, authority, or legitimacy. This dissertation, which centers on Catherine the Great, the empress of Russia between 1762 and 1796, takes on the concept of sovereignty as the exercise of supreme and untrammeled power, considered legitimate, and shows why sovereignty was itself the major desideratum. Sovereignty expressed parity with Western rulers, but it would allow Russian monarchs to bring order to their vast domain and to meaningfully govern the lives of their multitudinous subjects. This dissertation argues that Catherine the Great was a crucial figure in this process. Perceiving the confusion and disorder in how her predecessors exercised power, she recognized that sovereignty required both strong and consistent procedures as well as substantial collaboration with the broadest possible number of stakeholders. This was a modern conception of sovereignty, designed to regulate the swelling mechanisms of the Russian state. Catherine established her system through careful management of both her own activities and the institutions and servitors that she saw as integral to the system. -

Tourism Assessment of Roman-Catholic Sacral Objects Using Analytical Hierarchy Process (Ahp) – Case Study of Novi Sad, Petrovaradin and Sremska Kamenica

TURIZAM Volume 18, Issue 4 185-202 (2014) Tourism Assessment of Roman-Catholic Sacral Objects Using Analytical Hierarchy Process (Ahp) – Case Study of Novi Sad, Petrovaradin and Sremska Kamenica Igor Stamenković, Miroslav Vujičić* Received: August 2014 | Accepted: November 2014 Abstract Because of its geopolitical and tourist location and because of its ethnic composition, Novi Sad is known as one cosmopolitan city that grew to become the place of gathering and dialogue of many nations, -cul tures and religious communities. No matter if they are believers, agnostics, atheists, pilgrims, city tourists, travelling through or are the inhabitants, young, middle-aged or retired, all beneficent peo- ple can find here all the necessary information written on the account of rich religious and historical sources. The subject of this paper is the tourist valorization of the eight most attractive Roman-Catho- lic sacred objects in Novi Sad, Petrovaradin and Sremska Kamenica. In this paper the analyzed cul- tural and religious assets represent alternatives while indicators of the quantitative-qualitative method of assessment of cultural sites are used as criteria. And AHP gradually compares alternatives accord- ing to chosen criterion and measures their impact on the goal, which helps man to make the right deci- sion. From the results of the assessment of the analyzed sacred objects The Name of Mary Church with Catholic churchyard and Vicarage – Novi Sad is ranked as the most attractive site. Then, in second place is the Franciscan convert St. George the Martyr – Petrovaradin, followed by The Church of Snež- na Gospa in Tekije – Petrovaradin. Keywords: Analytical hierarchy process (AHP), Roman-Catholic sacral objects, Novi Sad, Petrova- radin, Sremska Kamenica. -

Lokacije Jesen 2016

AKCIJA JESENJEG UKLANJANJA KRUPNOG OTPADA PO MESNIM ZAJEDNICAMA ZA 2016. GODINU 01.09.-03.09.2016. MZ “DUNAV” 1. Kod kula na Beogradskom keju 2. Ugao Žarka Vasiljevi ća i Stevana Milovanova 3. Ugao ulice Šumadijske i Episkopa Visariona – kod Saobra ćajne škole „Heroj Pinki ” 02.09.-04.09.2016. MZ “ŽITNI TRG” 1. Bra će Jovandi ć iza broja 5 2. Ugao Vojvode Šupljikca i Đur ña Brankovi ća 3. Ugao Vojvode Bojovi ća i Vuka Karadži ća – ispred broja 5 03.09.-05.09.2016. MZ “STARI GRAD” 1. Trifkovi ćev trg 2. Trg Marije Trandafil – preko puta Matice srpske na parkingu 3. Ugao ulica Vojvode Putnika i Ive Lole Ribara 4. Ugao ulica Ilije Ognjanovi ća i Modene – na parkingu za taxi 04.09.-06.09.2016. MZ “PRVA VOJVO ĐANSKA BRIGADA” 1. Radni čka 17-19 2. Trg Galerija 3. Vase Staji ća 20 4. Bulevar Oslobo ñenja 115 05.09.-07.09.2016. MZ „BOŠKO BUHA” 1. Fruškogorska 6 2. Boška Buhe 8 3. Dragiše Brašovana 12 4. Ravani čka 1 06.09.-08.09.2016. MZ “LIMAN“ 1. Drage Spasi ć 2a 2. Ugao Veljka Petrovi ća i Milke Grgurove 3. Fruškogorska 21 4. Veljka Petrovi ća u blizini male škole „Jovan Popovi ć“, pored zgrada broj 6 i 8 07.09.-09.09.2016. MZ »SONJA MARINKOVI Ć« 1. Trg Ferenca Fehera, Polita Desan čića, Platonova, Jovana Đor ñevi ća - ulaz sa Trga Ferenca Fehera 6 2. Trg Neznanog junaka, Vojvode Miši ća, Sonje Marinkovi ć, Bulevar Mihajla Pupina - ulaz iz Vojvode Miši ća 19 3. -

ZRBG – Ghetto-Liste (Stand: 01.08.2014) Sofern Eine Beschäftigung I

ZRBG – Ghetto-Liste (Stand: 01.08.2014) Sofern eine Beschäftigung i. S. d. ZRBG schon vor dem angegebenen Eröffnungszeitpunkt glaubhaft gemacht ist, kann für die folgenden Gebiete auf den Beginn der Ghettoisierung nach Verordnungslage abgestellt werden: - Generalgouvernement (ohne Galizien): 01.01.1940 - Galizien: 06.09.1941 - Bialystok: 02.08.1941 - Reichskommissariat Ostland (Weißrussland/Weißruthenien): 02.08.1941 - Reichskommissariat Ukraine (Wolhynien/Shitomir): 05.09.1941 Eine Vorlage an die Untergruppe ZRBG ist in diesen Fällen nicht erforderlich. Datum der Nr. Ort: Gebiet: Eröffnung: Liquidierung: Deportationen: Bemerkungen: Quelle: Ergänzung Abaujszanto, 5613 Ungarn, Encyclopedia of Jewish Life, Braham: Abaújszántó [Hun] 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Kassa, Auschwitz 27.04.2010 (5010) Operationszone I Enciklopédiája (Szántó) Reichskommissariat Aboltsy [Bel] Ostland (1941-1944), (Oboltsy [Rus], 5614 Generalbezirk 14.08.1941 04.06.1942 Encyclopedia of Jewish Life, 2001 24.03.2009 Oboltzi [Yid], Weißruthenien, heute Obolce [Pol]) Gebiet Vitebsk Abony [Hun] (Abon, Ungarn, 5443 Nagyabony, 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Encyclopedia of Jewish Life 2001 11.11.2009 Operationszone IV Szolnokabony) Ungarn, Szeged, 3500 Ada 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Braham: Enciklopédiája 09.11.2009 Operationszone IV Auschwitz Generalgouvernement, 3501 Adamow Distrikt Lublin (1939- 01.01.1940 20.12.1942 Kossoy, Encyclopedia of Jewish Life 09.11.2009 1944) Reichskommissariat Aizpute 3502 Ostland (1941-1944), 02.08.1941 27.10.1941 USHMM 02.2008 09.11.2009 (Hosenpoth) Generalbezirk -

Strategy 2020 of Euroregion „Country of Lakes”

THIRD STEP OF EUROREGION “COUNTRY OF LAKES” Strategy 2020 of Euroregion „Country of Lakes” Project „Third STEP for the strategy of Euroregion “Country of lakes” – planning future together for sustainable social and economic development of Latvian-Lithuanian- Belarussian border territories/3rd STEP” "3-rd step” 2014 Strategy 2020 of Euroregion „Country of Lakes” This action is funded by the European Union, by Latvia, Lithuania and Belarus Cross-border Cooperation Programme within the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument. The Latvia, Lithuania and Belarus Cross-border Cooperation Programme within the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument succeeds the Baltic Sea Region INTERREG IIIB Neighbourhood Programme Priority South IIIA Programme for the period of 2007-2013. The overall strategic goal of the programme is to enhance the cohesion of the Latvian, Lithuanian and Belarusian border region, to secure a high level of environmental protection and to provide for economic and social welfare as well as to promote intercultural dialogue and cultural diversity. Latgale region in Latvia, Panevėžys, Utena, Vilnius, Alytus and Kaunas counties in Lithuania, as well as Vitebsk, Mogilev, Minsk and Grodno oblasts take part in the Programme. The Joint Managing Authority of the programme is the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of Lithuania. The web site of the programme is www.enpi-cbc.eu. The European Union is made up of 28 Member States who have decided to gradually link together their know-how, resources and destinies. Together, during a period of enlargement of 50 years, they have built a zone of stability, democracy and sustainable development whilst maintaining cultural diversity, tolerance and individual freedoms. -

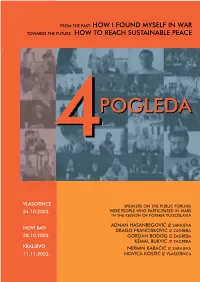

4 VIEWS. from the Past: How I Found Myself in War?

FROM THE PAST: HOW I FOUND MYSELF IN WAR TOWARDS THE FUTURE: HOW TO REACH SUSTAINABLE PEACE 44POGLEDPOGLEDAA VLASOTINCE SPEAKERS ON THE PUBLIC FORUMS 24.10.2003. WERE PEOPLE WHO PARTICIPATED IN WARS IN THE REGION OF FORMER YUGOSLAVIA ADNAN HASANBEGOVI] IZ SARAJEVA NOVI SAD DRAGO FRAN^I[KOVI] IZ ZAGREBA 28.10.2003. GORDAN BODOG IZ ZAGREBA KEMAL BUKVI] IZ ZAGREBA KRALJEVO NERMIN KARA^I] IZ SARAJEVA 11.11.2003. NOVICA KOSTI] IZ VLASOTINCA INITIATIVE AND ORGANISATION CENTAR ZA NENASILNU AKCIJU CENTRE FOR NONVIOLENT ACTION Office in Belgrade Office in Sarajevo Studentski trg 8, 11000 Beograd, SCG Radni~ka 104, 71000 Sarajevo, BiH Tel: +381 11 637-603, 637-661 Tel: +387 33 212-919, 267-880 Fax: +381 11 637-603 Fax: +387 33 212-919 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] www.nenasilje.org IN COOPERATION WITH UDRU@ENJE BORACA RATA 90. VLASOTINCE DRU[TVO ZA NENASILNU AKCIJU from Novi Sad OMLADINSKA ORGANIZACIJA KVART from Kraljevo Publication edited and articles written by activists of Centre for Nonviolent Action Adnan Hasanbegovi} Helena Rill Ivana Franovi} Milan Coli} Humljan Ned`ad Horozovi} Nenad Vukosavljevi} Sanja Deankovi} Tamara [midling About the public forums, the idea and the need Should we talk about the war? us, in whose name the wars had been lead protagonists are former soldiers, ‘Whatever happened it's all water and provoked. We carry our responsibility participants of the wars taking place in the under the bridge! It's everyone's fault. The because we have either supported creat- region of former Yugoslavia during the war is evil. -

Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart by Chrétien De Troyes

Lancelot, The Knight of the Cart by Chrétien de Troyes Translated by W. W. Comfort For your convenience, this text has been compiled into this PDF document by Camelot On-line. Please visit us on-line at: http://www.heroofcamelot.com/ Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart Table of Contents Acknowledgments......................................................................................................................................3 PREPARER'S NOTE: ...............................................................................................................................4 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY: ...............................................................................................................4 The Translation..........................................................................................................................................5 Part I: Vv. 1 - Vv. 1840..........................................................................................................................5 Part II: Vv. 1841 - Vv. 3684................................................................................................................25 Part III: Vv. 3685 - Vv. 5594...............................................................................................................45 Part IV: Vv. 5595 - Vv. 7134...............................................................................................................67 Endnotes...................................................................................................................................................84 -

The Education of Alexander and Nicholas Pavlovich Romanov The

Agata Strzelczyk DOI: 10.14746/bhw.2017.36.8 Department of History Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań The education of Alexander and Nicholas Pavlovich Romanov Abstract This article concerns two very different ways and methods of upbringing of two Russian tsars – Alexander the First and Nicholas the First. Although they were brothers, one was born nearly twen- ty years before the second and that influenced their future. Alexander, born in 1777 was the first son of the successor to the throne and was raised from the beginning as the future ruler. The person who shaped his education the most was his grandmother, empress Catherine the Second. She appoint- ed the Swiss philosopher La Harpe as his teacher and wanted Alexander to become the enlightened monarch. Nicholas, on the other hand, was never meant to rule and was never prepared for it. He was born is 1796 as the ninth child and third son and by the will of his parents, Tsar Paul I and Tsarina Maria Fyodorovna he received education more suitable for a soldier than a tsar, but he eventually as- cended to the throne after Alexander died. One may ask how these differences influenced them and how they shaped their personalities as people and as rulers. Keywords: Romanov Children, Alexander I and Nicholas I, education, upbringing The education of Alexander and Nicholas Pavlovich Romanov Among the ten children of Tsar Paul I and Tsarina Maria Feodorovna, two sons – the oldest Alexander and Nicholas, the second youngest son – took the Russian throne. These two brothers and two rulers differed in many respects, from their characters, through poli- tics, views on Russia’s place in Europe, to circumstances surrounding their reign. -

Serbia Guidebook 2013

SERBIA PREFACE A visit to Serbia places one in the center of the Balkans, the 20th century's tinderbox of Europe, where two wars were fought as prelude to World War I and where the last decade of the century witnessed Europe's bloodiest conflict since World War II. Serbia chose democracy in the waning days before the 21st century formally dawned and is steadily transforming an open, democratic, free-market society. Serbia offers a countryside that is beautiful and diverse. The country's infrastructure, though over-burdened, is European. The general reaction of the local population is genuinely one of welcome. The local population is warm and focused on the future; assuming their rightful place in Europe. AREA, GEOGRAPHY, AND CLIMATE Serbia is located in the central part of the Balkan Peninsula and occupies 77,474square kilometers, an area slightly smaller than South Carolina. It borders Montenegro, Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina to the west, Hungary to the north, Romania and Bulgaria to the east, and Albania, Macedonia, and Kosovo to the south. Serbia's many waterway, road, rail, and telecommunications networks link Europe with Asia at a strategic intersection in southeastern Europe. Endowed with natural beauty, Serbia is rich in varied topography and climate. Three navigable rivers pass through Serbia: the Danube, Sava, and Tisa. The longest is the Danube, which flows for 588 of its 2,857-kilometer course through Serbia and meanders around the capital, Belgrade, on its way to Romania and the Black Sea. The fertile flatlands of the Panonian Plain distinguish Serbia's northern countryside, while the east flaunts dramatic limestone ranges and basins. -

Jewish Citizens of Socialist Yugoslavia: Politics of Jewish Identity in a Socialist State, 1944-1974

JEWISH CITIZENS OF SOCIALIST YUGOSLAVIA: POLITICS OF JEWISH IDENTITY IN A SOCIALIST STATE, 1944-1974 by Emil Kerenji A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Todd M. Endelman, Co-Chair Professor John V. Fine, Jr., Co-Chair Professor Zvi Y. Gitelman Professor Geoffrey H. Eley Associate Professor Brian A. Porter-Szűcs © Emil Kerenji 2008 Acknowledgments I would like to thank all those who supported me in a number of different and creative ways in the long and uncertain process of researching and writing a doctoral dissertation. First of all, I would like to thank John Fine and Todd Endelman, because of whom I came to Michigan in the first place. I thank them for their guidance and friendship. Geoff Eley, Zvi Gitelman, and Brian Porter have challenged me, each in their own ways, to push my thinking in different directions. My intellectual and academic development is equally indebted to my fellow Ph.D. students and friends I made during my life in Ann Arbor. Edin Hajdarpašić, Bhavani Raman, Olivera Jokić, Chandra Bhimull, Tijana Krstić, Natalie Rothman, Lenny Ureña, Marie Cruz, Juan Hernandez, Nita Luci, Ema Grama, Lisa Nichols, Ania Cichopek, Mary O’Reilly, Yasmeen Hanoosh, Frank Cody, Ed Murphy, Anna Mirkova are among them, not in any particular order. Doing research in the Balkans is sometimes a challenge, and many people helped me navigate the process creatively. At the Jewish Historical Museum in Belgrade, I would like to thank Milica Mihailović, Vojislava Radovanović, and Branka Džidić. -

Russia's Empress-Navigator

Russia’s Empress-Navigator: Transforming Modes of Monarchy During the Reign of Anna Ivanovna, 1730-1740 Jacob Bell University of Illinois 2019 Winner of the James Madison Award for Excellence in Historical Scholarship The eighteenth century was a markedly volatile period in the history of Russia, seeing its development and international emergence as a European-styled empire. In narratives of this time of change, historians tend to view the century in two parts: the reign of Peter I (r. 1682-1725), who purportedly spurred Russia into modernization, and Catherine II (r. 1762-96), the German princess-turned-empress who presided over the culmination of Russia’s transformation. Yet, dismissal of nearly forty years of Russia’s history does a severe disservice to the sovereigns and governments that formed the process of change. Recently, Catherine Evtuhov turned her attention to investigating Russia under the rule of Elizabeth Petrovna (r. 1741-62), bolstering the conversation with a greater perspective of one of these “forgotten reigns,” but Elizabeth owed much to her post-Petrine predecessors. Specifically, Empress Anna Ivanovna (r. 1730-40) remains one of the most overlooked and underappreciated sovereigns of the interim between the “Greats.”1 Anna Ivanovna was born on February 7, 1693, the daughter of Praskovia Saltykova and Ivan V Alekseyvich (r. 1682-96), the son of Tsar Aleksey Mikhailovich (r. 1645-1676). When Anna was 1 Anna’s patronymic is also transliterated as Anna Ioannovna. I elected to use “Ivanovna” to closer resemble modern Russian. Lindsey Hughes, Russia in the Age of Peter the Great (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998); Catherine Evtuhov’s upcoming book is Russia in the Age of Elizabeth (1741-61). -

Turismhistoria-I-Norden

Turismhistoria i Norden Kolbe, Wiebke; Gustavsson, Anders 2018 Document Version: Förlagets slutgiltiga version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kolbe, W. (Red.), & Gustavsson, A. (2018). Turismhistoria i Norden. (Acta Academiae Regiae Gustavi Adolphi; Vol. 150). Kungliga Gustav Adolfs Akademien för svensk folkkultur. Total number of authors: 2 Creative Commons License: Annan General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 ACTA ACADEMIAE REGIAE GUSTAVI ADOLPHI CL Turismhistoria har under senare år blivit ett expanderande forskningsfält både 150 i Europa och i Norden. Boken ger en bred överblick över aktuell tvärveten- skaplig nordisk forskning som behandlar nordiska och vissa europeiska länder i ett turismhistoriskt perspektiv.