Eagle Syndrome with Hidden Stylocarotid Syndrome Examined Using Dynamic Ultrasonography: Illustrative Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eagle's Syndrome, Elongated Styloid Process and New

Musculoskeletal Science and Practice 50 (2020) 102219 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Musculoskeletal Science and Practice journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/msksp Masterclass Eagle’s syndrome, elongated styloid process and new evidence for pre-manipulative precautions for potential cervical arterial dysfunction Andrea M. Westbrook a,*, Vincent J. Kabbaz b, Christopher R. Showalter c a Method Manual Physical Therapy & Wellness, Raleigh, NC, 27617, USA b HEAL Physical Therapy, Monona, WI, USA c Program Director, MAPS Accredited Fellowship in Orthopedic Manual Therapy, Cutchogue, NY, 11935, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Introduction: Safety with upper cervical interventions is a frequently discussed and updated concern for physical Eagle’s syndrome therapists, chiropractors and osteopaths. IFOMPT developed the framework for safety assessment of the cervical Styloid spine, and this topic has been discussed in-depth with past masterclasses characterizing carotid artery dissection CAD and cervical arterial dysfunction. Our masterclass will expand on this information with knowledge of specific Carotid anatomical anomalies found to produce Eagle’s syndrome, and cause carotid artery dissection, stroke and even Autonomic Manipulation death. Eagle’s syndrome is an underdiagnosed, multi-mechanism symptom assortment produced by provocation of the sensitive carotid space structures by styloid process anomalies. As the styloid traverses between the internal and external carotid arteries, provocation of the vessels and periarterial sympathetic nerve fiberscan lead to various neural, vascular and autonomic symptoms. Eagle’s syndrome commonly presents as neck, facial and jaw pain, headache and arm paresthesias; problems physical therapists frequently evaluate and treat. Purpose: This masterclass aims to outline the safety concerns, assessment and management of patients with Eagle’s syndrome and styloid anomalies. -

Morfofunctional Structure of the Skull

N.L. Svintsytska V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 Ministry of Public Health of Ukraine Public Institution «Central Methodological Office for Higher Medical Education of MPH of Ukraine» Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukranian Medical Stomatological Academy» N.L. Svintsytska, V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 2 LBC 28.706 UDC 611.714/716 S 24 «Recommended by the Ministry of Health of Ukraine as textbook for English- speaking students of higher educational institutions of the MPH of Ukraine» (minutes of the meeting of the Commission for the organization of training and methodical literature for the persons enrolled in higher medical (pharmaceutical) educational establishments of postgraduate education MPH of Ukraine, from 02.06.2016 №2). Letter of the MPH of Ukraine of 11.07.2016 № 08.01-30/17321 Composed by: N.L. Svintsytska, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor V.H. Hryn, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor This textbook is intended for undergraduate, postgraduate students and continuing education of health care professionals in a variety of clinical disciplines (medicine, pediatrics, dentistry) as it includes the basic concepts of human anatomy of the skull in adults and newborns. Rewiewed by: O.M. Slobodian, Head of the Department of Anatomy, Topographic Anatomy and Operative Surgery of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Bukovinian State Medical University», Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor M.V. -

Calcio, Fósforo Y Vitamina D) Con Las Alteraciones Del Complejo Estilohioideo

TESIS DOCTORAL ANÁLISIS DE LA RELACIÓN ENTRE LOS PARÁMETROS ANALÍTICOS SÉRICOS DEL METABOLISMO ÓSEO (CALCIO, FÓSFORO Y VITAMINA D) CON LAS ALTERACIONES DEL COMPLEJO ESTILOHIOIDEO CARLOS MIGUEL SALVADOR RAMÍREZ Directores: Ana Sánchez del Rey y Agustín Martínez Ibargüen Facultad de Medicina y Enfermería 2018 (c)2018 CARLOS MIGUEL SALVADOR RAMIREZ “No tienes que ser grande para comenzar, pero tienes que comenzar para ser grande”. Zig Ziglar AGRADECIMIENTOS La elaboración del presente trabajo ha significado el resultado de un gran esfuerzo personal; pero deseo señalar, ya con la satisfacción de haber alcanzado el objetivo, la valiosa implicación y colaboración de todos quienes me ayudaron y animaron en esta labor. El inicio de mi interés por el estudio del complejo estilohioideo se dio desde mi etapa como residente ORL y como docente de prácticas universitarias, por lo que destaco la colaboración de parte del servicio de Otorrinolaringología del Hospital Universitario Basurto-Bilbao y de la cátedra de Anatomía y Embriología Humana UPV/EHU (Dra. Concepción Reblet López). A cada uno de los pacientes, quienes prestaron su tiempo y buena disposición a participar en el presente estudio. A los compañeros del Hospital Medina del Campo, en especial al equipo del servicio de Otorrinolaríngología, servicio de Laboratorio Clínico, servicio de Medicina Preventiva (Dra. María del Carmen Viña Simón), servicio de Radiodiagnóstico, residente: Dra. Jenny Dávalos Marín. A María Fé Muñoz Moreno, responsable de Metodología y Bioestadística de la Unidad de apoyo a la investigación del Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid, cuya colaboración ha sido fundamental para el análisis de los resultados encontrados. A Lourdes Sáenz de Castillo, de la Biblioteca del Campus de Álava UPV/EHU, por la colaboración en la obtención de material bibliográfico. -

Atlas of the Facial Nerve and Related Structures

Rhoton Yoshioka Atlas of the Facial Nerve Unique Atlas Opens Window and Related Structures Into Facial Nerve Anatomy… Atlas of the Facial Nerve and Related Structures and Related Nerve Facial of the Atlas “His meticulous methods of anatomical dissection and microsurgical techniques helped transform the primitive specialty of neurosurgery into the magnificent surgical discipline that it is today.”— Nobutaka Yoshioka American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Albert L. Rhoton, Jr. Nobutaka Yoshioka, MD, PhD and Albert L. Rhoton, Jr., MD have created an anatomical atlas of astounding precision. An unparalleled teaching tool, this atlas opens a unique window into the anatomical intricacies of complex facial nerves and related structures. An internationally renowned author, educator, brain anatomist, and neurosurgeon, Dr. Rhoton is regarded by colleagues as one of the fathers of modern microscopic neurosurgery. Dr. Yoshioka, an esteemed craniofacial reconstructive surgeon in Japan, mastered this precise dissection technique while undertaking a fellowship at Dr. Rhoton’s microanatomy lab, writing in the preface that within such precision images lies potential for surgical innovation. Special Features • Exquisite color photographs, prepared from carefully dissected latex injected cadavers, reveal anatomy layer by layer with remarkable detail and clarity • An added highlight, 3-D versions of these extraordinary images, are available online in the Thieme MediaCenter • Major sections include intracranial region and skull, upper facial and midfacial region, and lower facial and posterolateral neck region Organized by region, each layered dissection elucidates specific nerves and structures with pinpoint accuracy, providing the clinician with in-depth anatomical insights. Precise clinical explanations accompany each photograph. In tandem, the images and text provide an excellent foundation for understanding the nerves and structures impacted by neurosurgical-related pathologies as well as other conditions and injuries. -

Evaluation of the Elongation and Calcification Patterns of the Styloid Process with Digital Panoramic Radiography

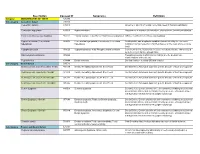

Evaluation of the Elongation and Calcification Patterns of the Styloid Process with Digital Panoramic Radiography Abstract Original Article Introdouction: typeThe styloid your textprocess(SP) ....... has the potential for cal- Khojastepour Leila 1, Dastan Farivar2, Ezoddini-Arda- cification and ossification. The aim of this study kani Fatemeh 3 was to investigate the prevalence of different pat- terns of elongation and calcification of the SP. Materials and methods: typeIn this your cross-sectional text ....... study, 400 digital pano- ramic radiographs taken for routine dental exam- ination in the dental school of Shiraz University were evaluated for the radiographic features of an elongated styloid process (ESP). The appar- 1 Professor, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial ent length of SP was measured with Scanora Radiology, Faculty of Dentistry, Shiraz University of software on panoramic of 350 patient who met Medial Science, Shiraz, Iran. the study criteria, ( 204 females and 146 males). 2 Dental student. Department of Oral and Maxillofa- Lengths greater than 30mm were consider as ESP. cial Radiology Faculty of Dentisty, Shiraz University ESP were also classified into three types based of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. on Langlais classification (elongated, pseudo -ar 3 Professor. Department of Oral and Maxillofacial ticulated; and segmented ). Data were analyzed Radiology Faculty of Dentisty, Shahid Sadough Uni- Results: versity of Medical Sciences Yazd, Iran . typeby the your Chi squaredtext ....... tests and Student’s t-tests . Results: Received:Received:17 May 2015 ESP was confirmed in 153 patients including 78 Accepted: 25 Jun 2015 males and 75 females (43.7%). The prevalence of ESP was significantly higher in males. -

Bilateral Ossified Stylohyoid Chain

Published online: 2020-03-02 NUJHS Vol. 2, No.2, June 2012, ISSN 2249-7110 Nitte University Journal of Health Science Case Report BILATERAL OSSIFIED STYLOHYOID CHAIN - A CASE STUDY Shivarama C.H.1, Bhat Shivarama2, Radhakrishna Shetty K.3, Vikram S.4, Avadhani R.5 1PG /Tutor, 2Associate Professor, 5Professor, 3Assistant Professor, 4Assistant Professor, Department of Anatomy, Yenepoya Medical College, Yenepoya University, Mangalore - 575 018, India. Correspondence: Ramakrishna Avadhani, Mobile : 98452 53560, E-mail : [email protected] Abstract : The styloid process is a slender bony projection that arises from the inferior surface of the temporal bone just beneath the external auditory meatus and closely related to the stylomastoid foramen. The normal length of SP in an adult is considered to be 20to 30mm however, it is very variably developed, ranging in length from a few millimetres to a few centimetres. The styloid process is developed at the cranial end of cartilage in the second visceral or hyoid arch by two centers: a proximal, for the tympanohyal, appearing before birth; the other, for the distal stylohyal, after birth. But sometimes the stylohyoid chain may form, that extends between the temporal and hyoid bones which are divided into 4 sections: tympanohyal, stylohyal, ceratohyal and hypohyal. Cartilage that is embryo logically located at the stylohyoid ligament may undergo calcification of varying degrees, which causes variations. Ossified stylohyal ligament parts may merge or leave gaps in between. The anatomy of styloid process has immense embryological, clinical, surgical importance. Keywords : Styloid process, Stylohyoid chain, Reichert's cartilage, Eagle's syndrome. Introduction : crossing lateral to the process in the parotid The styloid process (SP), slender, pointed, about 2.5 cm in gland1.Normally the SP tapers toward its tip that lies in the 2 length, projects anteroinferiorly from the temporal bone's pharyngeal wall lateral to the tonsillar fossa . -

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition Category ABNORMALITIES OF TEETH 426390 Subcategory Cementum Defect 399115 Cementum aplasia 346218 Absence or paucity of cellular cementum (seen in hypophosphatasia) Cementum hypoplasia 180000 Hypocementosis Disturbance in structure of cementum, often seen in Juvenile periodontitis Florid cemento-osseous dysplasia 958771 Familial multiple cementoma; Florid osseous dysplasia Diffuse, multifocal cementosseous dysplasia Hypercementosis (Cementation 901056 Cementation hyperplasia; Cementosis; Cementum An idiopathic, non-neoplastic condition characterized by the excessive hyperplasia) hyperplasia buildup of normal cementum (calcified tissue) on the roots of one or more teeth Hypophosphatasia 976620 Hypophosphatasia mild; Phosphoethanol-aminuria Cementum defect; Autosomal recessive hereditary disease characterized by deficiency of alkaline phosphatase Odontohypophosphatasia 976622 Hypophosphatasia in which dental findings are the predominant manifestations of the disease Pulp sclerosis 179199 Dentin sclerosis Dentinal reaction to aging OR mild irritation Subcategory Dentin Defect 515523 Dentinogenesis imperfecta (Shell Teeth) 856459 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield I 977473 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield II 976722 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; -

Radiopacities in Soft Tissue on Dental Radiographs: Diagnostic Considerations

www.sada.co.za / SADJ Vol 70 No. 2 CLINICAL REVIEW < 53 Radiopacities in soft tissue on dental radiographs: diagnostic considerations SADJ March 2015, Vol 70 no 2 p53 - p59 CEE Noffke1, EJ Raubenheimer2, NJ Chabikuli3 SUmmarY Radiopacities in soft tissue in the maxillofacial and oral ACRONYMS region frequently manifest on panoramic radiographs in CAC: calcified carotid plaque various locations and in several sizes and shapes. Accurate CBCT: cone beam computed tomography diagnosis is important as the finding may indicate serious CTC: calcified triticeous cartilage disease states. This manuscript provides guidelines for the GHH: greater horn of hyoid bone interpretation of soft tissue radiopacities seen on dental SHTC: superior horn of thyroid cartilage radiographs and recommends additional radiological views required to locate and diagnose the calcifications. tissue ossification is the formation of mature bone with or INTRODUCTION without bone marrow in an extra-skeletal site. Appropriate Soft tissue radiopacities include calcification, ossification or examples are elongation of the styloid process through foreign objects. The latter are excluded from this manuscript. ossification of the attached ligaments and bone formation Calcification is the deposition of calcium salts in tissue. The in synovial chondromatosis. pathogenesis is based on either dystrophic or metastatic mechanisms. Dystrophic calcification, which comprises Idiopathic calcification involves normal serum calcium the majority of soft tissue calcifications in the head and concentration and healthy tissue, and can as such not be neck region, is the result of soft tissue damage with tissue classified as either dystrophic or metastatic. Examples of degeneration and necrosis which attracts the precipitation this are tumorous calcinosis which presents with calcifica- of calcium salts. -

Overview of the Ossified Stylohyoid Ligament Based in More Than 1200 Forensic Autopsies

JOURNAL OF CLINICAL FORENSIC MEDICINE Journal of Clinical Forensic Medicine 13 (2006) 268–270 www.elsevier.com/locate/jcfm Original communication Overview of the ossified stylohyoid ligament based in more than 1200 forensic autopsies Theodore Vougiouklakis * University of Ioannina, Department of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology, University Campus, 451 10 Ioannina, Greece Received 25 May 2005; received in revised form 10 August 2005; accepted 28 September 2005 Available online 25 January 2006 Abstract The human stylohyoid chain presents considerable anatomic variability. In a personal series of 1215 forensic autopsies, eleven cases of complete ossification of the stylohyoid ligament have been revealed. Nine cases were bilateral and two cases were unilateral ossifications. A fractured ossified stylohyoid ligament was found in one case. The embryology and clinical significance of this condition has been men- tioned briefly. Ó 2005 Elsevier Ltd and AFP. All rights reserved. Keywords: Stylohyoid; Ossification; Forensic; Autopsy; Incidence; Fracture 1. Introduction 2. Methodology – Results The human stylohyoid chain includes the styloid pro- In a series of 1215 forensic autopsies performed in our cess (SP), the stylohyoid ligament (SHL), and the lesser department a careful dissection of the neck structures com- cornu of the hyoid bone. The stylohyoid chain is derived plex was done by 1 investigator. Only a macroscopic exam- from the second branchial arch and is sub-divided into ination of the stylohyoid chain was carried out; four parts: the segment known as tympanohyale, the sty- radiographs and histological slices were not regularly lohyale, the ceratohyale, and the hypohyale.1 The SHL is made. Therefore only a completely ossification of the a connective tissue band originating from the apex of the SHL could be detectable; for example, the extent of ossifi- SP and is attached to the lesser horn of the hyoid bone. -

Complete Ossification of the Stylohyoid Chain As Cause Of

JCDP Antônio Sérgio Guimarães et al 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1569 CASE REPORT Complete Ossification of the Stylohyoid Chain as Cause of Eagle’s Syndrome: A Very Rare Case Report 1Antônio Sérgio Guimarães, 2Daniel Humberto Pozza, 3Idercy Cabral de Castro, 4Iván Claudio Suazo Galdames, 5Sandro Palla ABSTRACT Conflict of interest: All authors disclose any financial and personal relationships with other people or organisations that To report on a patient with Eagle’s syndrome with a Aim: could inappropriately influence this manuscript. complete and very large ossification of the stylohyoid complex on the right side that to our best knowledge has never been published previously. INTRODUCTION Background: Eagle’s syndrome is characterized by a set of Eagle’s syndrome is classically characterized by dyspha- symptoms that are caused by the irritation of the neurovascular gia, foreign body sensation in the neck and oropharyngeal, and soft-tissues caused by an elongated styloid process or cervical and craniofacial pain.1-6 The pain is often exacer- ossification of stylohyoid ligament. bated by rotation of the head to the contralateral side, Case description: Because of the high discomfort and pain swallowing, extending the tongue, and yawning and may degree as well as limitations of mandibular and head mobility and radiate to distant areas. Indeed, a multitude of pain referral also the thickness of the ossified stylohyoid chain, the patient have been reported in the literature, for instance to the ear, was treated surgically by removing the hypertrophic segment. neck, tongue, teeth, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) area Conclusion: These symptoms subsided completely after the and even the chest and upper limbs.7 Risk factors for the surgical excision of the anomaly. -

Anatomical and Congenital Variations of Styloid Process of Temporal Bone in Indian Adult Dry Skull Bones

IJAE Vol. 124, n. 3: 509-516, 2019 ITALIAN JOURNAL OF ANATOMY AND EMBRYOLOGY Original research article Anatomical and Congenital Variations of Styloid Process of Temporal Bone in Indian Adult Dry Skull Bones 1, 2 3 Kalyan Chakravarthi Kosuri *, Venumadhav Nelluri , Siddaraju KS 1 Associate Professor, Department of Anatomy, Varun Arjun Medical College, Banthra-Shajahanpur - 242307, Uttar Pradesh, India 2 Assistent professor, Department of Anatomy, Melaka Manipal Medical College (MMMC), Manipal University, Manipal, and Karnataka, India 3 Lecturer, Department of Anatomy, KMCT Medical College, Manassery, Calicut, Kerala, India Abstract Background: Styloid process of temporal bone is clinically significant, because of anatomical or congenital variations in length, number, angulations as well as close proximity to many of the vital neurovascular structures in the neck. Abnormal or congenital variations of the sty- loid process may compress adjacent neurovascular structures and leads to symptoms of sty- lalgia (Eagle’s syndrome). Aim: Accordingly this study was aimed to evaluate the anatomical and congenital variations of styloid process of temporal bone in Indian adult dry skull bones. Materials and Methods: This study was carried out on 110 dry human skulls irrespective of age and sex at Varun Arjun medical college- Banthra,-UP, Melaka Manipal Medical College- Manipal and KMCT Medical College, Manassery- Calicut. All the skulls were macroscopi- cally inspected for the anatomical and congenital variations of styloid process of temporal bone. Photographs of the anatomical and congenital variations were taken for proper docu- mentation. Results: Out of 110 dry human skull bones we noted very rare unusual unilateral triple styloid processes in one skull bone, unusual bilateral double styloid processes in one skull bone and unilateral double styloid processes in right side of one skull bone. -

Oral Surgery Surgical Management of a Symptomatic Fractured, Ossified

ora! surgery oral medicine oral pathology with sc~c~r;orl.so,I endodontics CIrlC~dental radiology Volume 52, Number 6, December, 1981 oral surgery ROBERT B. SHIRA, D.D.S. School qf Dental Medicine, Tufts Universit\ I Kneeland Strwt Boston Massachusetts 02 I I I Surgical management of a symptomatic fractured, ossified stylohyoid ligament Stephen X. Solfanelli, D.M.D.,* Thomas W. Braun, D.M.D., Ph.D.,** and George C. Sotereanos, D.M.D., M.S.,*** Pittsburgh, Pa. PRESBYTERIAN-UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL Because of the number of symptoms on presentation and the overlapping with adjacent anatomic areas, cases of symptomatic styloid processes and ossified stylohyoid ligaments may be misdiagnosed and mistreated. Careful clinical examination, history, and evaluation of radiographs enhance accurate diagnosis. The case presented here required excision of the stylohyoid ligament by disarticulation at the hyoid bone and removal of the styloid process at the cranial base. As in this case, extraoral cervical incision may be the only rational surgical approach, depending on the size and extent of the process and its areas of articulation I n the case that follows a symptomatic, ossified temporomandibular Joint dysfunction. At the time of stylohyoid ligament was totally removed via an examination the patient’s chief complaint was that of extraoral approach. Despite radiographic and clini- left-sided otalgia and left-sided sore throat. She stated cal findings, the case was initially misdiagnosed. that 2 months previously she had developed a common While most of the literature suggests management cold which was followed by a constant. dull. left-sided sore throat and left auricular pain.