Warwick.Ac.Uk/Lib-Publications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal 21 – Seminar – Malaya, Korea & Kuwait

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 21 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. First published in the UK in 2000 Copyright 200: Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361-4231 Printed by Fotodirect Ltd Enterprise Estate, Crowhurst Road Brighton, East Sussex BN1 8AF Tel 01273 563111 3 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-Marshal N B Baldwin CB CBE Vice-Chairman Group Captain J D Heron OBE General Secretary Wing Commander C G Jefford MBE BA Membership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol AMRAeS Treasurer Desmond Goch Esq FCAA Members *J S Cox BA MA *Dr M A Fopp MA FMA FIMgt *Group Captain P J Greville RAF Air Commodore H A Probert MBE MA Editor, Publications Derek H Wood Esq AFRAeS Publications Manager Roy Walker Esq ACIB *Ex Officio 4 CONTENTS Malaya, Korea and Kuwait seminar Malaya 5 Korea 59 Kuwait 90 MRAF Lord Tedder by Dr V Orange 145 Book Reviews 161 5 RAF OPERATIONS 1948-1961 MALAYA – KOREA – KUWAIT WELCOMING ADDRESS BY SOCIETY CHAIRMAN Air Vice-Marshal Nigel Baldwin It is a pleasure to welcome all of you today. -

Scott's Discovery Expedition

New Light on the British National Antarctic Expedition (Scott’s Discovery Expedition) 1901-1904. Andrew Atkin Graduate Certificate in Antarctic Studies (GCAS X), 2007/2008 CONTENTS 1 Preamble 1.1 The Canterbury connection……………...………………….…………4 1.2 Primary sources of note………………………………………..………4 1.3 Intent of this paper…………………………………………………...…5 2 Bernacchi’s road to Discovery 2.1 Maria Island to Melbourne………………………………….…….……6 2.2 “.…that unmitigated fraud ‘Borky’ ……………………….……..….….7 2.3 Legacies of the Southern Cross…………………………….…….…..8 2.4 Fellowship and Authorship………………………………...…..………9 2.5 Appointment to NAE………………………………………….……….10 2.6 From Potsdam to Christchurch…………………………….………...11 2.7 Return to Cape Adare……………………………………….….…….12 2.8 Arrival in Winter Quarters-establishing magnetic observatory…...13 2.9 The importance of status………………………….……………….…14 3 Deeds of “Derring Doe” 3.1 Objectives-conflicting agendas…………………….……………..….15 3.2 Chivalrous deeds…………………………………….……………..…16 3.3 Scientists as Heroes……………………………….…….……………19 3.4 Confused roles……………………………….……..………….…...…21 3.5 Fame or obscurity? ……………………………………..…...….……22 2 4 “Scarcely and Exhibition of Control” 4.1 Experiments……………………………………………………………27 4.2 “The Only Intelligent Transport” …………………………………….28 4.3 “… a blasphemous frame of mind”……………………………….…32 4.4 “… far from a picnic” …………………………………………………34 4.5 “Usual retine Work diggin out Boats”………...………………..……37 4.6 Equipment…………………………………………………….……….38 4.8 Reflections on management…………………………………….…..39 5 “Walking to Christchurch” 5.1 Naval routines………………………………………………………….43 -

Sails of Glory Battle for the Seas a Sails of Glory Campaign

Sails Of Glory Battle for the Seas A Sails of Glory Campaign Time Sometime during the Napoleonic Wars 1803-1805. Info about the Campaign After Napoleon had won many great victories on land in Europe, and crushed every country in battle. France was the dominating power in Europe on land and the English were masters of the sea. Behind their wooden wall of ships, they were relatively safe from any invasion force. Napoleon wanted to change this and invade England. In March 1802 a peace treaty was signed between France and England in Amiens, France. But both countries were irritated and angry with each other’s actions in the aftermath of the peace treaty, and it was an uneasy peace. And after some diplomatic quarrels England declared war on France again in May 1803. After war broke out again, Napoleon started preparation for invasion of England – but to have success, he needed to take out the English fleet that protected the English Channel. From 1803 to 1805 a new army of 150 000-200,000 men, known as the Armée des côtes de l'Océan (Army of the Ocean Coasts) or the Armée d'Angleterre (Army of England), was gathered and trained at camps at Boulogne, Bruges and Montreuil. A large "National Flotilla" of invasion barges was built in Channel ports along the coasts of France and the Netherlands. A fleet of nearly 2000 craft. At the same time he made plans with the Spanish to assemble a large fleet, which was strong enough to challenge the English Navy, and make it possible for Napoleon to invade England. -

Frederick J. Krabbé, Last Man to See HMS Investigator Afloat, May 1854

The Journal of the Hakluyt Society January 2017 Frederick J. Krabbé, last man to see HMS Investigator afloat, May 1854 William Barr1 and Glenn M. Stein2 Abstract Having ‘served his apprenticeship’ as Second Master on board HMS Assistance during Captain Horatio Austin’s expedition in search of the missing Franklin expedition in 1850–51, whereby he had made two quite impressive sledge trips, in the spring of 1852 Frederick John Krabbé was selected by Captain Leopold McClintock to serve under him as Master (navigation officer) on board the steam tender HMS Intrepid, part of Captain Sir Edward Belcher’s squadron, again searching for the Franklin expedition. After two winterings, the second off Cape Cockburn, southwest Bathurst Island, Krabbé was chosen by Captain Henry Kellett to lead a sledging party west to Mercy Bay, Banks Island, to check on the condition of HMS Investigator, abandoned by Commander Robert M’Clure, his officers and men, in the previous spring. Krabbé executed these orders and was thus the last person to see Investigator afloat. Since, following Belcher’s orders, Kellett had abandoned HMS Resolute and Intrepid, rather than their return journey ending near Cape Cockburn, Krabbé and his men had to continue for a further 140 nautical miles (260 km) to Beechey Island. This made the total length of their sledge trip 863½ nautical miles (1589 km), one of the longest man- hauled sledge trips in the history of the Arctic. Introduction On 22 July 2010 a party from the underwater archaeology division of Parks Canada flew into Mercy Bay in Aulavik National Park, on Banks Island, Northwest Territories – its mission to try to locate HMS Investigator, abandoned here by Commander Robert McClure in 1853.3 Two days later underwater archaeologists Ryan Harris and Jonathan Moore took to the water in a Zodiac to search the bay, towing a side-scan sonar towfish. -

A Personal Narrative of the Origins of the British National Antarctic Expedition 1901-1904 by Sir Clements Markham, Edited and Introduced by Clive Holland

From The Introduction of Antarctic Obsession; A personal narrative of the origins of the British National Antarctic Expedition 1901-1904 by Sir Clements Markham, edited and introduced by Clive Holland. Alburgh, Harleston, Norfolk: Bluntisham Books - Erskine Press, 1986 Pages ix-xxiii I THE CAREER of Sir Clements Markham is almost unique in providing a living and active connection between several of the most outstanding periods of British polar exploration spanning nearly three-quarters of a century. As he is swift to point out in this Personal Narrative, he was acquainted with members of Sir James Clark Ross's pioneering Antarctic expedition of 1839-43 which discovered Ross Island and Victoria Land – regions which were to become the focus of Markham's attention in later life. He had no other direct connection with this expedition, however, for he was only nine years old when it sailed. His own first experience of polar exploration was in another major period of discovery: the search for Sir John Franklin's missing North-west Passage expedition of 1845-8, during which, over some 12 years, much of the Canadian Arctic archipelago was explored for the first time. His role was a modest one, as a midshipman on the Assistance during Captain H. T. Austin's search expedition of 1875-6, but the experience was evidently enough to confirm his enduring interest in the polar regions. His next Arctic role, to which he also refers in the Personal Narrative, was in the organization of the British Arctic Expedition of 1875-6, the primary objects of which were the attainment of the North Pole and the exploration of northern Greenland and Ellesmere Island. -

Lifeboats •Loval National Lilebodl Institution \ E Win Enea Mu Wings •^-^ «-^ Let This Uplifting Melody Inspire You

For everyone who helps save lives at sea Summer 2002 va National Lifeboat Ins' r 1 I Her Majesty opeffg her Gokteajybjjge celebrations with a visit to name the new lifeboat at Falmouth Lifeboats •loval National Lilebodl Institution \ e win enea mu wings •^-^ «-^ Let this uplifting melody inspire you Inscribed inside the lid is a message that lasts a lifetime for a daughter Sculptural porcelain butterfly with shimmering gold mother accents graces the lid sister friend Six Sparkling Swarovski crystals gratiddaugh ter grandmother 22-carat gold bands, 22-carat gold-finished feet and delicate golden \ heading REMARKABLE VALUE AT JUST £24.95 (+p&p) 7^ Actual size approximate!]! 3W inches wide created from the delicate watercolour-on-silk paintings of Lena Liu 080065U999 mile Rrlcrcnic. 178643 t takes an artist of rare talent and insight to capture the beauty PRIORITY RESERVATION FORM Iand grace of butterflies as well as a sense of the freedom they "Flights of Fancy" inspire. Now, the supremely gifted artist Lena Liu achieves both in Limit: one ul cat.li mu*k l><>\ pi i mlk-uor her "Flights of Fancy"music box, available exclusively through Bradford Editions. To: Bradford Editions, PO Box 653, Stoke-on-Trent ST4 4RA "Flights of Fancy" enchants the eye with its graceful fluted shape Please enter my reservation tor the "Flights of Fancy" music and Lena Liu's delicate watercolour artwork, depicting ivory box by Lena Liu. I understand that I NEED SEND NO dogwood blossoms and garnet-hued raspberries, surrounding two MONEY NOW. Please invoice me for £24.95 (plus £2.99 spectacular Red-spotted Purple butterflies. -

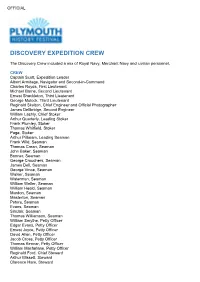

Discovery: Crew List

OFFICIAL DISCOVERY EXPEDITION CREW The Discovery Crew included a mix of Royal Navy, Merchant Navy and civilian personnel. CREW Captain Scott, Expedition Leader Albert Armitage, Navigator and Second-in-Command Charles Royds, First Lieutenant Michael Barne, Second Lieutenant Ernest Shackleton, Third Lieutenant George Mulock, Third Lieutenant Reginald Skelton, Chief Engineer and Official Photographer James Dellbridge, Second Engineer William Lashly, Chief Stoker Arthur Quarterly, Leading Stoker Frank Plumley, Stoker Thomas Whitfield, Stoker Page, Stoker Arthur Pilbeam, Leading Seaman Frank Wild, Seaman Thomas Crean, Seaman John Baker, Seaman Bonner, Seaman George Crouchers, Seaman James Dell, Seaman George Vince, Seaman Walker, Seaman Waterman, Seaman William Weller, Seaman William Heald, Seaman Mardon, Seaman Masterton, Seaman Peters, Seaman Evans, Seaman Sinclair, Seaman Thomas Williamson, Seaman William Smythe, Petty Officer Edgar Evans, Petty Officer Ernest Joyce, Petty Officer David Allan, Petty Officer Jacob Cross, Petty Officer Thomas Kennar, Petty Officer William Macfarlane, Petty Officer Reginald Ford, Chief Steward Arthur Blissett, Steward Clarence Hare, Steward OFFICIAL Dowsett, Steward Gilbert Scott, Steward Roper, Cook Brett, Cook Charles Clarke, 2nd Cook Clarke, Laboratory Assistant Buckridge, Laboratory Assistant Fred Dailey, Carpenter James Duncan, Carpenter’s Mate & Shipwright Thomas Feather, Boatswain (Bosun) Miller, Sailmaker Hubert, Donkeyman SCIENTIFIC Dr George Murray, Chief Scientist (left the ship at Cape Town) Louis Bernacchi, Physicist Hartley Ferrar, Geologist Thomas Vere Hodgson, Marine Biologist Reginald Koettlitz, Doctor Edward Wilson, Junior Doctor and Zoologist . -

Sunset for the Royal Marines? the Royal Marines and UK Amphibious Capability

House of Commons Defence Committee Sunset for the Royal Marines? The Royal Marines and UK amphibious capability Third Report of Session 2017–19 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 30 January 2018 HC 622 Published on 4 February 2018 by authority of the House of Commons The Defence Committee The Defence Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Ministry of Defence and its associated public bodies. Current membership Rt Hon Dr Julian Lewis MP (Conservative, New Forest East) (Chair) Leo Docherty MP (Conservative, Aldershot) Martin Docherty-Hughes MP (Scottish National Party, West Dunbartonshire) Rt Hon Mark Francois MP (Conservative, Rayleigh and Wickford) Graham P Jones MP (Labour, Hyndburn) Johnny Mercer MP (Conservative, Plymouth, Moor View) Mrs Madeleine Moon MP (Labour, Bridgend) Gavin Robinson MP (Democratic Unionist Party, Belfast East) Ruth Smeeth MP (Labour, Stoke-on-Trent North) Rt Hon John Spellar MP (Labour, Warley) Phil Wilson MP (Labour, Sedgefield) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications Committee reports are published on the Committee’s website at www.parliament.uk/defcom and in print by Order of the House. Evidence relating to this report is published on the inquiry page of the Committee’s website. Committee staff Mark Etherton (Clerk), Dr Adam Evans (Second Clerk), Martin Chong, David Nicholas, Eleanor Scarnell, and Ian Thomson (Committee Specialists), Sarah Williams (Senior Committee Assistant), and Carolyn Bowes and Arvind Gunnoo (Committee Assistants). -

January 1993 ARGONAUTA

ARGONAUTA The Newsletter of The Canadian Nautical Research Society Volume X Number One January 1993 ARGONAUTA Founded 1984 by Kenneth S. Mackenzie ISSN No. 0843-8544 EDITORS Lewis R. FISCHER Olaf U. JANZEN Gerald E. PANTING MANAGING EDITOR Margaret M. GULLIVER ARGONAUTA EDITORIAL OFFICE Maritime Studies Research Unit Memorial University of Newfoundland St. John's, Nfld. A1C 5S7 Telephones: (709) 737-8424/(709) 737-2602 FAX: (709) 737-4569 ARGONAUTA is published four times per year in January, April, July and October and is edited for the Canadian Nautical Research Society within the Maritime Studies Research Unit at Memorial University of Newfoundland. THE CANADIAN NAUTICAL RESEARCH SOCIETY Honourary President: Niels JANNASCH, Halifax Executive Officers Liaison Committee President: WA.B. DOUGLAS, Ottawa Chair: Fraser M. MCKEE, Markdale Pasl President: Barry M. GOUGH, Waterloo Atlantic: David FLEMMING, Halifax Vice-President: M. Stephen SALMON, Ottawa Quebec: Eileen R. MARCIL, Charlcsbourg Vice-President: Olaf U. JANZEN, Corner Brook Ontario: Maurice D. SMITH, Kingston Councillor: Garth S. WILSON, Ottawa Western: Christon I. ARCHER, Calgary Councillor: John SUMMERS, Toronto Pacific: John MACFARLANE, Victoria Councillor: Marven MOORE, Halifax Arctic: D. Richard VALPY, Yellowknife Councillor: Fraser M. MCKEE, Markdale Secretary: Lewis R. FISCHER, St. John's CNRS MAILING ADDRESS Treasurer: G. Edward REED, Ottawa Assistant Treasurer: Faye KERT, Ottawa P.O. Box 7008, Station J Ottawa, Ontario K2A 3Z6 Annual Membership, which includes four issues of ARGO Individual $25 NA UTA and four issues of The Northem Mariner: Institution $50 JANUARY 1993 ARGONAUTA 1 should be reviewed, or that only "good" books should be reviewed. Not only does this give the reviews editor a power CONTENTS he has no desire to wield-- the power to impose his tastes and standards on the membership--it also implies, quite Edilorials 1 incorrectly, that "scholarly" books are, by their nature, "good" Presidenl's Corner 2 books. -

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society The Old angbournianP Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society First published in the UK 2020 The Old Pangbournian Society Copyright © 2020 The moral right of the Old Pangbournian Society to be identified as the compiler of this work is asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, “Beloved by many. stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any Death hides but it does not divide.” * means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the Old Pangbournian Society in writing. All photographs are from personal collections or publicly-available free sources. Back Cover: © Julie Halford – Keeper of Roll of Honour Fleet Air Arm, RNAS Yeovilton ISBN 978-095-6877-031 Papers used in this book are natural, renewable and recyclable products sourced from well-managed forests. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro, designed and produced *from a headstone dedication to R.E.F. Howard (30-33) by NP Design & Print Ltd, Wallingford, U.K. Foreword In a global and total war such as 1939-45, one in Both were extremely impressive leaders, soldiers which our national survival was at stake, sacrifice and human beings. became commonplace, almost routine. Today, notwithstanding Covid-19, the scale of losses For anyone associated with Pangbourne, this endured in the World Wars of the 20th century is continued appetite and affinity for service is no almost incomprehensible. -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

North Atlantic Press Gangs: Impressment and Naval-Civilian Relations in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, 1749-1815 by Keith Mercer Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia August 2008 © Copyright by Keith Mercer, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-43931-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-43931-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Dyndal, Gjert Lage (2009) Land Based Air Power Or Aircraft Carriers? the British Debate About Maritime Air Power in the 1960S

Dyndal, Gjert Lage (2009) Land based air power or aircraft carriers? The British debate about maritime air power in the 1960s. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/1058/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Land Based Air Power or Aircraft Carriers? The British debate about Maritime Air Power in the 1960s Gjert Lage Dyndal Doctor of Philosophy dissertation 2009 University of Glasgow Department for History Supervisors: Professor Evan Mawdsley and Dr. Simon Ball 2 Abstract Numerous studies, books, and articles have been written on Britains retreat from its former empire in the 1960s. Journalists wrote about it at the time, many people who were involved wrote about it in the immediate years that followed, and historians have tried to put it all together. The issues of foreign policy at the strategic level and the military operations that took place in this period have been especially well covered. However, the question of military strategic alternatives in this important era of British foreign policy has been less studied.