John Wayne: the 'Duke' Cast a Long Shadow in Arizona

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women Architects

E-Newsletter | May 2012 Women Architects What do the Hearst Castle in California and many of the buildings in Grand Canyon National Park have in common? They were designed by women architects! In this month's newsletter, we feature two early women architects - Julia Morgan and Mary Colter. California's first licensed woman architect, Julia Morgan, studied architecture in Paris. After failing the entrance examination to the École des Beaux-Arts twice, she learned that the faculty had failed her deliberately to discourage her admission. Undeterred, she gained admission and received her certificate in architecture in 1902. By 1904, she had opened her own architecture practice in San Francisco. After receiving acclaim when one of her buildings on the Mills College campus withstood the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, she was commissioned to rebuild the damaged Fairmont Hotel. With this project Morgan's reputation as well as her architecture practice was assured. Julia Morgan Morgan designed her first building for the YWCA in Oakland in 1912. She then began work on the YWCA's seaside retreat Asilomar, near Monterey, which has hosted thousands of visitors since its founding in 1913. Today Asilomar is a state historical park. Morgan's work on the Hearst Castle, which is also now a state historical monument, cemented her reputation. The Castle, located at San Simeon, has attracted more than 35 million visitors since it opened to the public in 1958. Architect Mary Colter was asked by railroad magnate Fred Harvey to design hotels and restaurants along the Santa Fe Railway route, with the objective of bringing tourists to the southwestern United States. -

When Dick and Nan Walden Met at A

the stallions picante jullyen v (*jullyen el jamaal x precious v) and macnificent rs (maclintock v x ravvens skylark). by GARY DEARTH hen Dick and Nan Walden met at a environmental attorney and consultant for over wedding in 1998, Dick was a lifelong fifteen years before she met Dick. Her professional W farmer and rancher, and Nan was a city background also included serving as Chief of Staff to girl. Dick grew up with ranch horses and had been Senator Bill Bradley and counsel to Senator Daniel riding since he was four years old. He attended the Patrick Moynihan. Thacher School in Ojai, California, where horses Nan was a typical horse crazy young girl. “I had are part of the curriculum. While there, he competed Breyer horses complete with handmade blankets in horse shows, gymkhanas, and packed out in the with their names embroidered on them. I read every Sespe wilderness. horse book written, including all the Walter Farley Meanwhile, Nan Stockholm Walden earned books. Dad bought me Shetland and Hackney ponies her B.A. in Environmental Studies from Stanford when I was a girl, but sadly, I had terrible childhood University. Later she graduated from the Stanford asthma,” she said. “When I was in law school at University Law School where she was the Stanford Stanford, I received a series of shots, which were Environmental Law Society President. She was an much improved by then. It changed my life.” KENNEALLY PHOTO KENNEALLY SONADO˜ > 1 < WORLD Dick was skeptical, “Green rider, high-energy horse, she will probably hurt or kill us both,” he thought. -

Movies and Cultural Contradictions

< I 1976 Movies and Cultural Contradictions FRANK P. TOMASULO In its bicentennial year, the United States was wracked by dis- illusionment and mistrust of the government. The Watergate scandal and the evacuation of Vietnam were still fresh in everyone's mind. Forced to deal with these traumatic events, combined with a lethargic economy (8.5 per- cent unemployment, energy shortages and OPEC price hikes of 5 to 10 per- cent, high inflation (8.7 percent and rising), and the decline of the U.S. dollar on international currency exchanges, the American national psyche suffered from a climate of despair and, in the phrase made famous by new California governor Jerry Brown the previous year, “lowered expectations.” President Gerald R. Ford's WIN (Whip Inflation Now) buttons--did nothing bolster consumer/investor confidence and were widely perceived to be a public rela- tions gimmick to paper over structural difficulties in the financial system. Intractable problems were apparent: stagflation, political paranoia, collective anxiety, widespread alienation, economic privation, inner-city decay, racism, and violence. The federal government's “misery index,” a combination of the unemployment rate and the rate of inflation, peaked at 17 percent. In short, there was a widespread perception that the foundations of the American Dream bad been shattered by years of decline and frustration. Despite these negative economic and social indicators in the material world, the nation went ahead with a major feel-good diversion, the bicen- tennial celebration that featured the greatest maritime spectacle in Ameri- can history: “Operation Sail,” a parade of sixteen “Tall Ships,” fifty-three warships, and more than two hundred smaller sailing vessels in New York harbor. -

Reflexive Regionalism and the Santa Fe Style

Reflexive Regionalism and the Santa Fe Style Ron Foresta Department of Geography University of Tennessee, Knoxville Abstract:The Santa Fe Style is an assembly of cultural features associated with the city of Santa Fe and its surrounding Upper Rio Grande Valley. The style, often dismissed as a confection for tourists because of its gloss and worldliness, is in fact a manifestation of reflexive regionalism. This overlooked cultural process occurs when worldly outsiders fashion regional traits into responses to the life challenges that they and their extra- regional reference groups face. In this case, outsiders fashioned what they found in early-twentieth-century Santa Fe into responses to challenges that accompanied the rise of American industrial capitalism. Threats to elite hegemony, the destruction of established lifeways, and the need for new perspectives on American society were prominent among the challenges to which the Santa Fe Style responded. Reflexive regionalism is thus the kind of cultural process that Regulation Theory posits but has found difficult to convincingly identify in the real world, i.e., one that adapts individuals and societies to periodic shifts in the logic and practices of capitalism. I examine seven individuals who made signal contributions to the Santa Fe Style. Each reveals a key facet of Santa Fe’s reflexive regionalism. Together they show how this process created the Santa Fe Style and, more generally, how it works as an engine of cultural invention. The key concepts here are reflexive regionalism, the Santa Fe Style, cosmopolitanism, Regulation Theory, the work of the age, and the project of the self. -

Ore· Deposits of The

fu\fE-199 UNITED STATES ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISSION GRAND JUNCTION OPERATIONS OFFICE EXPLORATION DIVISION SUMMARY OF URANIUM EXPLORATION IN THE LUKACHUKAI MOUNTAINS, APACHE COUNTY, ARIZONA 1950-1955 CONTRACT NOS. AT(30-1) 1021, 1139, 1263, 1364; AT(05-l) 234, 257 By Raymond F. Kosatka UNEDITED MANUSCRIPT Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed in this report, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference therein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. March 30, 1956 Grand Junction, Colorado Summary of Uranium Exploration In The Lukachukai Mountains, Apache County, Arizona 1950 - 1955 CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................... iii Introduction. ••••••••••••• 0 ..................................... l Exploration and Mining History...................................... 1 Genera 1 Geology.. • • • • • • • • • • .. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • .. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • -

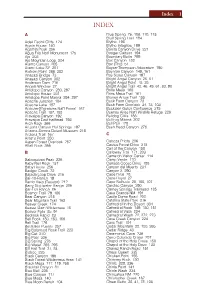

Index 1 INDEX

Index 1 INDEX A Blue Spring 76, 106, 110, 115 Bluff Spring Trail 184 Adeii Eechii Cliffs 124 Blythe 198 Agate House 140 Blythe Intaglios 199 Agathla Peak 256 Bonita Canyon Drive 221 Agua Fria Nat'l Monument 175 Booger Canyon 194 Ajo 203 Boundary Butte 299 Ajo Mountain Loop 204 Box Canyon 132 Alamo Canyon 205 Box (The) 51 Alamo Lake SP 201 Boyce-Thompson Arboretum 190 Alstrom Point 266, 302 Boynton Canyon 149, 161 Anasazi Bridge 73 Boy Scout Canyon 197 Anasazi Canyon 302 Bright Angel Canyon 25, 51 Anderson Dam 216 Bright Angel Point 15, 25 Angels Window 27 Bright Angel Trail 42, 46, 49, 61, 80, 90 Antelope Canyon 280, 297 Brins Mesa 160 Antelope House 231 Brins Mesa Trail 161 Antelope Point Marina 294, 297 Broken Arrow Trail 155 Apache Junction 184 Buck Farm Canyon 73 Apache Lake 187 Buck Farm Overlook 34, 73, 103 Apache-Sitgreaves Nat'l Forest 167 Buckskin Gulch Confluence 275 Apache Trail 187, 188 Buenos Aires Nat'l Wildlife Refuge 226 Aravaipa Canyon 192 Bulldog Cliffs 186 Aravaipa East trailhead 193 Bullfrog Marina 302 Arch Rock 366 Bull Pen 170 Arizona Canyon Hot Springs 197 Bush Head Canyon 278 Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum 216 Arizona Trail 167 C Artist's Point 250 Aspen Forest Overlook 257 Cabeza Prieta 206 Atlatl Rock 366 Cactus Forest Drive 218 Call of the Canyon 158 B Calloway Trail 171, 203 Cameron Visitor Center 114 Baboquivari Peak 226 Camp Verde 170 Baby Bell Rock 157 Canada Goose Drive 198 Baby Rocks 256 Canyon del Muerto 231 Badger Creek 72 Canyon X 290 Bajada Loop Drive 216 Cape Final 28 Bar-10-Ranch 19 Cape Royal 27 Barrio -

2017 Fernald Caroline Dissert

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE VISUALIZATION OF THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEST: ETHNOGRAPHY, TOURISM, AND AMERICAN INDIAN SOUVENIR ARTS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By CAROLINE JEAN FERNALD Norman, Oklahoma 2017 THE VISUALIZATION OF THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEST: ETHNOGRAPHY, TOURISM, AND AMERICAN INDIAN SOUVENIR ARTS A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS BY ______________________________ Dr. W. Jackson Rushing, III, Chair ______________________________ Mr. B. Byron Price ______________________________ Dr. Alison Fields ______________________________ Dr. Kenneth Haltman ______________________________ Dr. David Wrobel © Copyright by CAROLINE JEAN FERNALD 2017 All Rights Reserved. For James Hagerty Acknowledgements I wish to extend my most sincere appreciation to my dissertation committee. Your influence on my work is, perhaps, apparent, but I am truly grateful for the guidance you have provided over the years. Your patience and support while I balanced the weight of a museum career and the completion of my dissertation meant the world! I would certainly be remiss to not thank the staff, trustees, and volunteers at the Millicent Rogers Museum for bearing with me while I finalized my degree. Your kind words, enthusiasm, and encouragement were greatly appreciated. I know I looked dreadfully tired in the weeks prior to the completion of my dissertation and I thank you for not mentioning it. The Couse Foundation, the University of Oklahoma’s Charles M. Russell Center, and the School of Visual Arts, likewise, deserve a heartfelt thank you for introducing me to the wonderful world of Taos and supporting my research. A very special thank you is needed for Ginnie and Ernie Leavitt, Carl Jones, and Byron Price. -

Flagstaff, Ash Fork, Grand Canyon, Kayenta, Leupp, Page, Sedona, Seligman, Tuba City, Williams

ARIZONA TELEPHONE DIRECTORIES WHITE PAGES CITY: Flagstaff, Ash Fork, Grand Canyon, Kayenta, Leupp, Page, Sedona, Seligman, Tuba City, Williams YEAR: July 1964 TELEPHONE DIRECTORY Flagstaff - Ash Fork - Grand Canyon - Kayenta Leupp - Page - Sedona - Seligman Tuba City - Williams JULY 1964 AREA CODE 602 MOUNTAIN STATES TELEPHONE NAME AND AREA TELEPHONE ADDRESS CODE - — — - - Hi late Long Distance keeps your outlook happy, your humor good, and your smile bright. Pick up your phone and go visiting tonight! • ft C a 1 ft THE MOUNTAIN STATES TELEPHONE AND TELEGRAPH COMPANY DISTRICT HEADQUARTERS ARIZONA EXECUTIVE OFFICES 24 West Aspen Avenue 16 West McDowell Read Flagstaff, Arizona Phoenix, Arizona 774-3311 258-3611 TELEPHONE DIRECTORY JUL 24 1964 FLAGSTAFF - ASHFORK - GRAND CANYON - KAYENTA - LEUPP PAGE - SEDONA - SELIGMAN - TUBA CITY - WILLIAMS JULY 1964 CONTENTS ALPHABETICAL LISTINGS Page 8 AREA MAPS Blue Section CIVIC INFORMATION Blue Section CLASSIFIED SECTION Yellow Pages EMERGENCY CALLS: FIRE / POLICE Pages 1 and 3 GENERAL INFORMATION: TELEPHONE SERVICE Page 7 HOW TO PLACE TELEPHONE CALLS Out-of-Town Calls / Pages 5-6-7 Use of Dial Telephone / Page 4 TELEPHONE BUSINESS OFFICES Page 2 TELEPHONE SERVICE CALLS EMERGENCIES ASSISTANCE IN DIALING Oporator BUSINESS OFFICE Soo Rage 2 Write down the telephone numbers you will need in case of INFORMATION Flagstaff, Page, Sedona 113 emergency. Your FIRE and POLICE numbers are listed on .Ash Fork, Grand Canyon, Kayenta, Leupp, Page 3. Seligman, Tuba City, Williams Oporator Long Distance Information. Soo Pago* 5 & 6 LONG DISTANCE Operator Service Oporator POLICE. ^AMBULANCE- Direct Distance Dialing Soo Pago* 5 & 6 MOBILE TELEPHONE CALLS Oporator REPAIR SERVICE FIRE. -

Appreciating Mary Colter and Her Roots in St

Louis and Maybelle: Somewhere Out in the West John W. Larson —page 13 Winter 2011 Volume 45, Number 4 “We Can Do Better with a Chisel or a Hammer” Appreciating Mary Colter and Her Roots in St. Paul Diane Trout-Oertel, page 3 Artist Arthur F. Matthews painted the portrait of Mary Jane Elizabeth Colter seen above in about 1890, when she graduated from the California School of Design. Colter subsequently taught art for many years at Mechanic Arts High School in St. Paul and later designed eight buildings at the Grand Canyon National Park in Arizona. Shown here is Hermit’s Rest, located at the westernmost stop on the south rim, a building that Colter designed in 1914. The Colter portrait is reproduced courtesy of the Arizona Historical Society, Flagstaff, Ariz. Photograph of Hermit’s Rest courtesy of Alexander Vertikoff. Hermit’s Rest copyright © Alexander Vertikoff. RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORY RAMSEY COUNTY Executive Director Priscilla Farnham Founding Editor (1964–2006) Virginia Brainard Kunz Editor Hıstory John M. Lindley Volume 45, Number 4 Winter 2011 RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY THE MISSION STATEMENT OF THE RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY BOARD OF DIRECTORS ADOPTED BY THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS ON DECEMBER 20, 2007: Paul A. Verret The Ramsey County Historical Society inspires current and future generations President Cheryl Dickson to learn from and value their history by engaging in a diverse program First Vice President of presenting, publishing and preserving. William Frels Second Vice President Julie Brady Secretary C O N T E N T S Carolyn J. Brusseau Treasurer 3 “We Can Do Better with a Chisel and a Hammer” Thomas H. -

Contemporary Nostalgia

Contemporary Nostalgia Edited by Niklas Salmose Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Humanities www.mdpi.com/journal/humanities Contemporary Nostalgia Contemporary Nostalgia Special Issue Editor Niklas Salmose MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor Niklas Salmose Linnaeus University Sweden Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Humanities (ISSN 2076-0787) from 2018 to 2019 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/ humanities/special issues/Contemporary Nostalgia). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03921-556-0 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03921-557-7 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Wikimedia user jarekt. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/ wiki/File:Cass Scenic Railroad State Park - Shay 11 - 05.jpg. c 2019 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Special Issue Editor ...................................... vii Niklas Salmose Nostalgia Makes Us All Tick: A Special Issue on Contemporary Nostalgia Reprinted from: Humanities 2019, 8, 144, doi:10.3390/h8030144 ................... -

Havasupai-Arizona's Hidden Paradise

The LumberjackThunday. Octobw 30.1980 Photo Editor LaurU RobUon. 523-4921 PHOTO PAGE 3 Far-left, Mooney Falls is dwarfed from 1,000 feet up but It Is actually the largest falls in Havasu Canyon, falling over 100 feet. Left, Starting from Hualapai Hilltop, this backpacker made the 11-mile hike to the campsite in three hours bul received a blistered fcot for his ef forts. Below, Tom Hathaway, 15, Coconino Hh?h School sophomore, on his second trip with Associated Students of Northern Arizona University to Havasupai, said about the trip, "There was a lol of biking but the sites were beautiful." that says that when these rocks fall, the Supai village will c Havasupai-Arizona’s hidden paradise There is a place in Arizona where the waterfalls spill into Tim Mohr, Flagstaff junior, added “The sites were breathtak aquamarine pools; this place is Havasupai. ing, but the hike was murder." Located on the Supai Indian reservation about 60 miles nortlv Marlin W. Kollasch, Phoenix junior, said, “ Havasu Canyon of Grand Canyon Caverns, Havasupai offers the hiker a spec * is fantastic, it's unsurpassed for its beauty. Hopefully people tacle unmatched throughout the world. will keep it that way.” Last weekend 38 NAU students and one Coconino High Linda McNutt.Glendale freshman, said, “The whole canyon School student took the winding path down to the falls. Perhaps is awesome. The trip was very invigorating and really wor the best way to describe the whole adventure comes from the thwhile." hikers themselves. Janet L. Woodman, Scottsdale senior, said, Lisa Hawdon, Richboro, Penn, junior, probably summed it "The trip was great. -

SCRAPBOOK of MOVIE STARS from the SILENT FILM and Early TALKIES Era

CINEMA Sanctuary Books 790 - Madison Ave - Suite 604 212 -861- 1055 New York, NY 10065 [email protected] Open by appointment www.sanctuaryrarebooks.com Featured Items THE FIRST 75 ISSUES OF FILM CULTURE Mekas, Jonas (ed.). Film Culture. [The First 75 Issues, A Near Complete Run of "Film Culture" Magazine, 1955-1985.] Mekas has been called “the Godfather of American avant-garde cinema.” He founded Film Culture with his brother, Adolfas Mekas, and covered therein a bastion of avant-garde and experimental cinema. The much acclaimed, and justly famous, journal features contributions from Rudolf Arnheim, Peter Bogdanovich, Stan Brakhage, Arlene Croce, Manny Farber, David Ehrenstein, John Fles, DeeDee Halleck, Gerard Malanga, Gregory Markopoulos, Annette Michelson, Hans Richter, Andrew Sarris, Parker Tyler, Andy Warhol, Orson Welles, and many more. The first 75 issues are collected here. Published from 1955-1985 in a range of sizes and designs, our volumes are all in very good to fine condition. Many notable issues, among them, those designed by Lithuanian Fluxus artist, George Macunias. $6,000 SCRAPBOOK of MOVIE STARS from the SILENT FILM and early TALKIES era. Staple-bound heavy cardstock wraps with tipped on photo- illustration of Mae McAvoy, with her name handwritten beneath; pp. 28, each with tipped-on and hand-labeled film stills and photographic images of celebrities, most with tissue guards. Front cover a bit sunned, lightly chipped along the edges; internally bright and clean, remarkably tidy in its layout and preservation. A collection of 110 images of actors from the silent film and early talkies era, including Inga Tidblad, Mona Martensson, Corinne Griffith, Milton Sills, Norma Talmadge, Colleen Moore, Charlie Chaplin, Lillian Gish, and many more.