American Dance Marathons, 1928-1934, and the Social Drama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ii. Dialogue Program

II. DIALOGUE PROGRAM Introduction Through its Dialogue Program, PASSIA has ever since its foundation striven both to promote free expression within Palestinian society and to foster a better understanding of Palestinian affairs, be they in the domestic or international context. In doing so, PASSIA has earned a reputation for providing a unique forum for dialogue and exchange and for serving as a catalyst for civic debate. Central to these efforts has been the presentation and analysis of a plurality of Palestinian perspectives and approaches. Topics addressed and discussed cover a wide range of subjects broadly and specifically related to the Palestine Question, from historical aspects to the current Middle East Peace Process and internal Palestinian affairs. The PASSIA Dialogue Program is divided into the following three sections: Roundtable Meetings: PASSIA invites a speaker (and sometimes a discussant as well) to lecture on a certain topic, followed by a discussion with the audience present. Particularly topical issues are sometimes the subject of a series of lectures by as varied a range of speakers as possible. These meetings aim to promote thought and debate among Palestinians and between Palestinians and their foreign counterparts. Briefings: PASSIA frequently provides a venue for encounters, dialogue and discussions involving representatives and organizations from various backgrounds. These meetings focus on current Palestinian affairs and are designed to build bridges of communication and understanding between Palestinians from different streams of society and to develop constructive and focused academic contact between Palestinians and Israelis. PASSIA has also hosted numerous meetings in which resident diplomats and visiting foreign missions are invited to discuss Palestinian affairs and exchange thoughts and opinions concerning the situation in the Palestinian Territories. -

Revolution by the Book

AK PRESS PUBLISHING & DISTRIBUTION SUMMER 2009 AKFRIENDS PRESS OF SUMM AK PRESSER 2009 Friends of AK/Bookmobile .........1 Periodicals .................................51 Welcome to the About AK Press ...........................2 Poetry/Theater...........................39 Summer Catalog! Acerca de AK Press ...................4 Politics/Current Events ............40 Prisons/Policing ........................43 For our complete and up-to-date AK Press Publishing Race ............................................44 listing of thousands more books, New Titles .....................................6 Situationism/Surrealism ..........45 CDs, pamphlets, DVDs, t-shirts, Forthcoming ...............................12 Spanish .......................................46 and other items, please visit us Recent & Recommended .........14 Theory .........................................47 online: Selected Backlist ......................16 Vegan/Vegetarian .....................48 http://www.akpress.org AK Press Gear ...........................52 Zines ............................................50 AK Press AK Press Distribution Wearables AK Gear.......................................52 674-A 23rd St. New & Recommended Distro Gear .................................52 Oakland, CA 94612 Anarchism ..................................18 (510)208-1700 | [email protected] Biography/Autobiography .......20 Exclusive Publishers CDs ..............................................21 Arbeiter Ring Publishing ..........54 ON THE COVER : Children/Young Adult ................22 -

Judson Dance Theater: the Work Is Never Done

Judson Dance Theater: The Work is Never Done Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done The Museum of Modern Art, New York September 16, 2018-February 03, 2019 MoMA, 11w53, On View, 2nd Floor, Atrium MoMA, 11w53, On View, 2nd Floor, Contemporary Galleries Gallery 0: Atrium Complete Charles Atlas video installation checklist can be found in the brochure Posters CAROL SUMMERS Poster for Elaine Summers’ Fantastic Gardens 1964 Exhibition copy 24 × 36" (61 × 91.4 cm) Jerome Robbins Dance Division, New York Public Library, GIft of Elaine Summers Gallery 0: Atrium Posters Poster for an Evening of Dance 1963 Exhibition copy Yvonne Rainer Papers, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles Gallery 0: Atrium Posters Poster for Concert of Dance #13, Judson Memorial Church, New York (November 19– 20, 1963) 1963 11 × 8 1/2" (28 × 21.6 cm) Judson Memorial Church Archive, Fales Library & Special Collections, New York University Libraries Gallery 0: Atrium Posters Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done Gallery 0: Atrium Posters Poster for Concert of Dance #5, America on Wheels, Washington, DC (May 9, 1963) 1963 8 1/2 × 11" (21.6 × 28 cm) Judson Memorial Church Archive, Fales Library & Special Collections, New York University Libraries Gallery 0: Atrium Posters Poster for Steve Paxton’s Afternoon (a forest concert), 101 Appletree Row, Berkeley Heights, New Jersey (October 6, 1963) 1963 8 1/2 × 11" (21.6 × 28 cm) Judson Memorial Church Archive, Fales Library & Special Collections, New York University Libraries Gallery 0: Atrium Posters Flyer for -

Report of the Committee on Treatment of Persons Awaiting Court Action

REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON TREAT- MENT OF PERSONS AWAITING COURT AC- TION AND MISDEMEANANT PRISONERS IMPORTANCE OF THE SUBJECT This Committee holds the opinion that no subject to be con- sidered by this Congress is of more importance than the treat- ment of persons awaiting court action and misdemeanant pris- oners. In the first place they far outnumber all other persons who come under the consideration of the penologist. The census of 1910 shows that about 92 per cent of all sentenced prisoners were misdemeanant prisoners committed to county jails, workhouses, and houses of correction. This makes no account of prisoners awaiting trial. The United States Census Bureau did not deem it necessary to enumerate this important class of prisoners. In the second place, the two classes of prisoners considered by this Committee presumably include those who are most reformable, because it includes those who are imprisoned for the first time. -^ We believe that to its most earnest society ought expend J efforts in behalf of those who are not yet hardened in crime. / Everyone recognizes the difficulty of reclaiming those who have become fixed in criminal habits. The hope of reforming a be- C ginner, in the early stages of wrongdoing, is five times greater ) than the hope of reforming one who has become experienced in J crime. In 1833, nearly ninety years ago, DeToqueville published his book, The Penitentiary System in the United States. In com- menting on American jails he says (pages 153-154): "Prisons were observed, which included persons convicted of the worst crimes, and a remedy has been applied where the greatest evil appeared ; other prisons, where the same evil exists, but where it makes less fearful ravages, have been forgotten; yet to neglect the less vicious, in order to labor only for the reform of great and hardened criminals, is the same as if only the most infirm were 3 502648 attended to in a hospital; and, in order to take care of patients, perhaps incurable, those who might be easily restored to health were left without any attention. -

Thursday, May 24, 2018

American Literature Association A Coalition of Societies Devoted to the Study of American Authors 29th Annual Conference on American Literature San Francisco, CA May 24-27, 2018 Conference Director Leslie Petty Rhodes College This on-line draft of the program is designed to provide information to participants in our 29th conference and an opportunity to make corrections. Please send your corrections directly to the conference director at [email protected] as soon as possible. Updates will be published on-line weekly until we go to press. Please note that the printed program will be available at the conference. Opportunities to advertise in the printed program are available at a cost of $250 per camera ready page – further information may be obtained by contacting Professor Alfred Bendixen, the Executive Director of the ALA, at [email protected] Audio-Visual Equipment: The program also lists the audio-visual equipment that has been requested for each panel. The ALA normally provides a digital projector and screen to those who have requested it at the time the panel or paper is submitted. Individuals will need to provide their own laptops and those using Macs are advised to bring along the proper cable/adaptor to hook up with the projector. Please note that we no longer provide vcrs or overhead projectors or tape players and we cannot provide internet access. Registration: Participants must pre-register for the conference by going to the website at http://americanliteratureassociation.org/ala-conferences/registration-and-conference- fees/ 1 and either completing on line-registration which allows you to pay with a credit card or completing the registration form and mailing it along with the appropriate check to the address indicated. -

ALA2018 Finalprogram

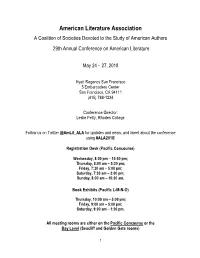

American Literature Association A Coalition of Societies Devoted to the Study of American Authors 29th Annual Conference on American Literature May 24 – 27, 2018 Hyatt Regency San Francisco 5 Embarcadero Center San Francisco, CA 94111 (415) 788-1234 Conference Director: Leslie Petty, Rhodes College Follow us on Twitter @AmLit_ALA for updates and news, and tweet about the conference using #ALA2018! Registration Desk (Pacific Concourse) Wednesday, 8:00 pm – 10:00 pm; Thursday, 8:00 am – 5:30 pm; Friday, 7:30 am – 5:00 pm; Saturday, 7:30 am – 3:00 pm; Sunday, 8:00 am – 10:30 am. Book Exhibits (Pacific L-M-N-O) Thursday, 10:00 am – 5:00 pm; Friday, 9:00 am – 5:00 pm; Saturday, 9:00 am – 1:00 pm. All meeting rooms are either on the Pacific Concourse or the Bay Level (Seacliff and Golden Gate rooms) 1 American Literature Association A Coalition of Societies Devoted to the Study of American Authors 29th Annual Conference on American Literature May 24 – 27, 2017 Acknowledgments: On behalf of the American Literature Association, I would like to thank the author societies, as well as everyone who proposed a panel or a paper or offered to chair a session. It has been a pleasure working with you to create such a wonderful program. My sincere thanks to my colleagues at Rhodes College for their moral support and good advice. In particular, Lorie Yearwood has my deep, sincere and lasting gratitude for her meticulous work and good humor. As always, the ALA is indebted to Georgia Southern University and the Department of Literature and Philosophy for their invaluable support. -

JUDSONOW the Work Is Never Done

DANSPACE PROJECT PLATFORM 2012: JUDSONOW The work is never done. Sanctuary always needed. -Steve Paxton In Memory of Reverend Howard Moody (1921-2012) 3 Published by Danspace Project, New York, on the occasion of PLATFORM 2012: Judson Now. First edition ©2012 Danspace Project All rights reserved under pan-American copyright conventions. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Every reasonable effort has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions. Inquires should be addressed to: Danspace Project St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery 131 East 10th Street New York, NY 10003 danspaceproject.org EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Judy Hussie-Taylor EDITOR AND SCHOLAR-IN-RESIDENCE Jenn Joy MANAGING EDITOR Lydia Bell CURATORIAL FELLOW Katrina De Wees RESEARCHER Adrienne Rooney PHOTOGRAPHER-IN-RESIDENCE Ian Douglas WRITERS-IN-RESIDENCE Huffa Frobes-Cross Danielle Goldman PRINTER Symmetry DESIGNER Judith Walker Cover image: Carolee Schneemann, Score for Banana Hands (1962). Photo by Russ Heller. DANSPACE PROJECT PLATFORM 2012: JUDSONOW JUDSON Remy Charlip Feinberg Geoffrey Hendricks PARTICIPANTS Pandit Chatur Lal Crystal Field Donna Hepler 1962-66*: Lucinda Childs William Fields Fred Herko Carolyn Chrisman June Finch Clyde Herlitz Carolyn Adams Nancy Christofferson Jim Finney George Herms Charles Adams Sheila Cohen Pamela Finney Geoffrey Heyworth Olga Adorno Klüver Hunt Cole George Flynn Dick Higgins Felix Aeppli -

In the United States District Court for the District of Marland Greenbelt Division

Case 8:11-cv-03220-RWT Document 43-18 Filed 12/07/11 Page 1 of 28 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MARLAND GREENBELT DIVISION MS.PATRICIA FLETCHER, ) et al., ) ) Civ. Action No.: RWT-11-3220 ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) ) LINDA LAMONE in her official ) capacity as State Administrator of ) Elections for the state of Maryland; ) And ROBERT L. WALKER in his ) official capacity as Chairman of the ) State Board of Elections, ) ) Defendants. ) ____________________________________) DECLARATION AND EXPERT REPORT OF PETER MORRISON, Ph.D. Case 8:11-cv-03220-RWT Document 43-18 Filed 12/07/11 Page 2 of 28 2 DECLARATION OF PETER MORRISON I, PETER MORRISON, being competent to testify, hereby affirm on my personal knowledge as follows: 1. My name is Peter A. Morrison. I reside at 3 Eat Fire Springs Rd., Nantucket, MA 02554. I have been retained as an expert to undertake a demographic analysis of the statewide growth and residential concentration of the Black population of Maryland for the Fannie Lou Hamer Coalition. I am being compensated at a rate of $215 per hour. I am retired from the RAND Corporation where I was Senior Demographer and the founding director of RAND’s Population Research Center. My academic background and publications are detailed in my attached vita (Exhibit A). Case 8:11-cv-03220-RWT Document 43-18 Filed 12/07/11 Page 3 of 28 3 I. INTRODUCTION 2. This report responds to the request by counsel for plaintiffs that I undertake a demographic analysis of the statewide growth and residential concentration of the Black population of Maryland. -

DRAFT: May 3, 2018 American Literature Association

DRAFT: May 3, 2018 American Literature Association A Coalition of Societies Devoted to the Study of American Authors 29th Annual Conference on American Literature San Francisco, CA May 24-27, 2018 Conference Director Leslie Petty Rhodes College Follow us on Twitter @AmLit_ALA for updates and news, and tweet about the conference using #ALA2018! This on-line draft of the program is designed to provide information to participants in our 29th conference and an opportunity to make corrections. Please send your corrections directly to the conference director at [email protected] as soon as possible. Updates will be published on-line weekly until we go to press. Please note that the printed program will be available at the conference. Opportunities to advertise in the printed program are available at a cost of $250 per camera ready page – further information may be obtained by contacting Professor Alfred Bendixen, the Executive Director of the ALA, at [email protected] Audio-Visual Equipment: The program also lists the audio-visual equipment that has been requested for each panel. The ALA normally provides a digital projector and screen to those who have requested it at the time the panel or paper is submitted. Individuals will need to provide their own laptops and those using Macs are advised to bring along the proper cable/adaptor to hook up with the projector. Please note that we no longer provide vcrs or overhead projectors or tape players and we cannot provide internet access. Registration: Participants must pre-register for the conference by going to the website at 1 http://americanliteratureassociation.org/ala-conferences/registration-and-conference- fees/ and either completing on line-registration which allows you to pay with a credit card or completing the registration form and mailing it along with the appropriate check to the address indicated. -

Yayoi Kusama: Biography and Cultural Confrontation, 1945–1969

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects CUNY Graduate Center 2012 Yayoi Kusama: Biography and Cultural Confrontation, 1945–1969 Midori Yamamura The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/4328 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] YAYOI KUSAMA: BIOGRAPHY AND CULTURAL CONFRONTATION, 1945-1969 by MIDORI YAMAMURA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2012 ©2012 MIDORI YAMAMURA All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Anna C. Chave Date Chair of Examining Committee Kevin Murphy Date Executive Officer Mona Hadler Claire Bishop Julie Nelson Davis Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract YAYOI KUSAMA: BIOGRAPHY AND CULTURAL CONFRONTATION, 1945-1969 by Midori Yamamura Adviser: Professor Anna C. Chave Yayoi Kusama (b.1929) was among the first Japanese artists to rise to international prominence after World War II. She emerged when wartime modern nation-state formations and national identity in the former Axis Alliance countries quickly lost ground to U.S.-led Allied control, enforcing a U.S.-centered model of democracy and capitalism. -

ADDTOD.C.FUNDS Outskirts of Deridder

LIQUOR SHIP SEIZED. GRANT MEMORIAL TO BE UNVfelLED APRIL 27. PASTOR GIVEN TAR COAT. DEBATEINSENATE Schooner Flying British Flag Held. THINKSENATEWILL t<oulsianan Is Then Set Down in | E Crew Arrested. Main Street. PORTSMOUTH. Va.. February 25 . LAKE CHARLES. La.. February 25.. The motor schooner Emerald of Die- Rev. W. B. Bennett wu taken to the OH TREATY SOON by, Nova Scotia, flying the British ADDTOD.C.FUNDS outskirts of Deridder. La... this morning PLEADFORBQNUS flag, was seised this afternoon as a and tarred and feathered, according to rum-runner, while fleeing from Vir¬ a telephone message received here. Committee Four- ginia waters. Her cargo, said to conr Committee Members Predict Bennett is alleged to have deserted his I Thirty Sign Letter Approves slst of more than one thousand cases family and broken Jail in Meridian. | Opposing of liquor for New York delivery was Miss., some time ago. Power Pact and Sub¬ seized along with the ship's papers Increasing of Several Bpnnett is said to have received word Sales Tax, But Urging Use as Allen . and the captain, signed John early this morning to come to his office. marine Treaties. Williams, and the entire crew have House Figures. Upon his arrival there he was met by * of Refunded Bonds. been taken Into custody pending ex¬ Predictions that the District appro¬ crowd of men. who forced him into an amination before the United States' priation bill as It will be reported automobile and drove him to the coun¬ HOPE FOR EARLY ACTION commissioner Monday. by the Senate committee will pro¬ try. -

1 Ishmael Reed "Southern Writer" Might Not Come to Mind When One

1 Ishmael Reed "Southern writer" might not come to mind when one thinks of author, playwright, publisher, and poet Ishmael Reed. Although born in Chattanooga, Tennessee, in 1938, his stay in the south was short lived. Reed has spent the majority of his life in New York and California. East Tennessee, with memories of Lookout Mountain and the Tennessee River, is a place he rarely visits, but is the first of his several homes. He has written about Tennessee, but his writing is not regional. The words of Ishmael Reed break down barriers that divide Americans and celebrate "Americanness" in all its manifestations. Young Ishmael attended public schools throughout his adolescent education, where he gained interest in playing jazz instruments such as violin and trombone. Along with his musical gifts, his writing skills were always prominent. At the youthful age of thirteen, he began to write a short column on jazz for the Empire Star Weekly, where his knowledge of music melded with his love of writing. Reed attended evening classes at the then-private Buffalo University. During days he earned money by working as a secretary at a nearby public library where his writing abilities flourished. However, in 1960 Reed had to withdraw and end his formal higher education due to, in his own words in an interview with Henry Louis Gates, "a dire shortage of funds" and to get away from "artificial social and class distinctions." Those same financial problems forced him into Talbert Mall Housing Project in Buffalo, where he witnessed firsthand the extreme consequences of poverty and social injustice.