Secrecy As Security Composition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edward R. Murrow Awards

TW MAIN 10-06-08 A 13 TVWEEK 10/2/2008 5:49 PM Page 1 TELEVISIONWEEK October 6, 2008 13 INSIDE SPECIAL SECTION NewsproTHE STATE OF TV NEWS All About ABC The network’s news division will take home half the awards in national/syndie categories. Page 14 Engrossing Stories NBC News’ Bob Dotson gets fourth Murrow for stories that make viewers “late for the bus.” Page 14 Eyeing CBS’ Efforts CBS News, CBSnews.com are honored for excellence in real and virtual worlds. Page 16 ‘Sports Center’ a Winner for ESPN Saga of former tennis champ Andrea Jaeger offers perspective on her unique journey. Page 17 EDWARD R. Murrows Laud Excellence at Network, Local Levels MURROW By Debra Kaufman AWARDS Special to TelevisionWeek Honoring: The Radio-Television News Directors Association gathers Oct. 13 Survival Saga ESPN Deportes’ “Sobrevivientes” Excellence in at the Grand Hyatt Hotel in New York to present the 2008 Edward R. electronic tracks survivors of a rugby team’s plane crash in the Andes. Page 18 journalism Murrow Awards. Where: Grand In addition to recipients of the 38th Murrow Awards, winners Personal Touch Hyatt, New York of the RTNDA/Unity Awards—which acknowledge news organi- Seattle’s KOMO-TV takes large- When: Monday, market laurel for its “Problem Oct. 13 zations’ commitment to covering issues of diversity in their com- Solvers” franchise. Page 18 Presenters: munities—will be honored. Out of an initial pool of 3,459 entries, Lester Holt, Community Service Soledad O’Brien, 54 news organizations are being honored with 77 awards. In the small-market race, WJAR-TV Maggie “Everyone is proud of receiving an Edward R. -

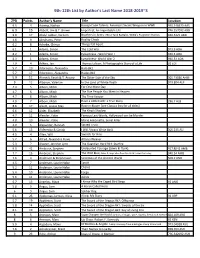

9Th-12Th List by Author's Last Name 2018-2019~S

9th-12th List by Author's Last Name 2018-2019~S ZPD Points Author's Name Title Location 9.5 4 Aaseng, Nathan Navajo Code Talkers: America's Secret Weapon in WWII 940.548673 AAS 6.9 15 Abbott, Jim & T. Brown Imperfect, An Improbable Life 796.357092 ABB 9.9 17 Abdul-Jabbar, Kareem Brothers in Arms: 761st Tank Battalio, WW2's Forgotten Heroes 940.5421 ABD 4.6 9 Abrahams, Peter Reality Check 6.2 8 Achebe, Chinua Things Fall Apart 6.1 1 Adams, Simon The Cold War 973.9 ADA 8.2 1 Adams, Simon Eyewitness - World War I 940.3 ADA 8.3 1 Adams, Simon Eyewitness- World War 2 940.53 ADA 7.9 4 Adkins, Jan Thomas Edison: A Photographic Story of a Life 92 EDI 5.7 19 Adornetto, Alexandra Halo Bk1 5.7 17 Adornetto, Alexandra Hades Bk2 5.9 11 Ahmedi, Farah & T. Ansary The Other Side of the Sky 305.23086 AHM 9 12 Albanov, Valerian In the Land of White Death 919.804 ALB 4.3 5 Albom, Mitch For One More Day 4.7 6 Albom, Mitch The Five People You Meet in Heaven 4.7 6 Albom, Mitch The Time Keeper 4.9 7 Albom, Mitch Have a Little Faith: a True Story 296.7 ALB 8.6 17 Alcott, Louisa May Rose in Bloom [see Classics lists for all titles] 6.6 12 Alder, Elizabeth The King's Shadow 4.7 11 Alender, Katie Famous Last Words, Hollywood can be Murder 4.8 10 Alender, Katie Marie Antoinette, Serial Killer 4.9 5 Alexander, Hannah Sacred Trust 5.6 13 Aliferenka & Ganda I Will Always Write Back 305.235 ALI 4.5 4 Allen, Will Swords for Hire 5.2 6 Allred, Alexandra Powe Atticus Weaver 5.3 7 Alvarez, Jennifer Lynn The Guardian Herd Bk1: Starfire 9.0 42 Ambrose, Stephen Undaunted Courage -

Documents/DD/Issuances/Dtm/ DTM%2019-004.PDF?Ver=2020-03-17- 140438-090

No. 19-123 In the Supreme Court of the United States SHARONELL FULTON, ET AL. Petitioners, V. CITY OF PHILADELPHIA, PENNSYLVANIA, ET AL., Respondents. On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit BRIEF OF FORMER SERVICE SECRETARIES AND THE MODERN MILITARY ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA AS AMICI CURIAE SUPPORTING RESPONDENTS PETER PERKOWSKI MICHAEL E. BERN MODERN MILITARY Counsel of Record ASSOCIATION OF GEORGE C. CHIPEV AMERICA L. ALLISON HERZOG 1725 Eye Street, NW LATHAM & WATKINS LLP Suite 300 555 Eleventh Street, NW Washington, DC 20006 Suite 1000 (202) 328-3244 Washington, DC 20004 (202) 637-2200 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae Secretaries Ray Mabus, Deborah Lee James, and Eric Fanning, and the Modern Military Association of America i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ..................................... iv INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ................................1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .....................................4 ARGUMENT ...............................................................6 I. LGBTQ SERVICE MEMBERS, THEIR SPOUSES, AND THEIR FAMILIES ARE INTEGRAL TO THE MILITARY’S ABILITY TO ACCOMPLISH ITS MISSION ............................................................6 A. LGBTQ Service Members Are Integral To America’s Armed Forces.........6 B. Military Families, Including LGBTQ Military Families, Also Are Integral To The Military’s Ability To Accomplish Its Mission ..............................8 C. For Many LGBTQ Service Members, The Ability To Adopt Is Critical To Having A Fulfilling Family Life .............. 12 II. PERMITTING RELIGIOUS DISCRIMINATION ON THE BASIS OF SEXUAL ORIENTATION WOULD BURDEN LGBTQ SERVICE MEMBERS AND FRUSTRATE THE MILITARY’S ABILITY TO ACHIEVE ITS MISSION .......... 14 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS—Continued Page A. Anti-Discrimination Requirements Ensure Equal Access And Protect LGBTQ Persons, Including Service Members, From Discrimination By Providers Of A Wide Range Of Critical Government-Funded Services .....................................................16 B. -

The Civilian Impact of Drone Strikes

THE CIVILIAN IMPACT OF DRONES: UNEXAMINED COSTS, UNANSWERED QUESTIONS Acknowledgements This report is the product of a collaboration between the Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School and the Center for Civilians in Conflict. At the Columbia Human Rights Clinic, research and authorship includes: Naureen Shah, Acting Director of the Human Rights Clinic and Associate Director of the Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School, Rashmi Chopra, J.D. ‘13, Janine Morna, J.D. ‘12, Chantal Grut, L.L.M. ‘12, Emily Howie, L.L.M. ‘12, Daniel Mule, J.D. ‘13, Zoe Hutchinson, L.L.M. ‘12, Max Abbott, J.D. ‘12. Sarah Holewinski, Executive Director of Center for Civilians in Conflict, led staff from the Center in conceptualization of the report, and additional research and writing, including with Golzar Kheiltash, Erin Osterhaus and Lara Berlin. The report was designed by Marla Keenan of Center for Civilians in Conflict. Liz Lucas of Center for Civilians in Conflict led media outreach with Greta Moseson, pro- gram coordinator at the Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School. The Columbia Human Rights Clinic and the Columbia Human Rights Institute are grateful to the Open Society Foundations and Bullitt Foundation for their financial support of the Institute’s Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, and to Columbia Law School for its ongoing support. Copyright © 2012 Center for Civilians in Conflict (formerly CIVIC) and Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America. Copies of this report are available for download at: www.civiliansinconflict.org Cover: Shakeel Khan lost his home and members of his family to a drone missile in 2010. -

Blue Light: America's First Counter-Terrorism Unit Jack Murphy

Blue Light: America's First Counter-Terrorism Unit Jack Murphy On a dark night in 1977, a dozen Green Berets exited a C-130 aircraft, parachuting into a very different type of war. Aircraft hijackings had become almost commonplace to the point that Johnny Carson would tell jokes about the phenomena on television. But it was no laughing matter for the Department of Defense, who realized after the Israeli raid on Entebbe, that America was woefully unprepared to counter terrorist attacks. This mission would be different. The Special Forces soldiers guided their MC1-1B parachutes towards the ground but their element became separated in the air, some of the Green Berets landing in the trees. The others set down alongside an airfield, landing inside a thick cloud of fog. Their target lay somewhere through the haze, a military C-130 aircraft that had been captured by terrorists. Onboard there were no hostages, but a black box, a classified encryption device that could not be allowed to fall into enemy hands. Airfield seizures were really a Ranger mission, but someone had elected to parachute in an entire Special Forces battalion for the operation. The HALO team was an advanced element, inserted ahead of time to secure the aircraft prior to the main assault force arriving. Despite missing a number of team members at the rally point, the Green Berets knew they were quickly approaching their hit time. They had to take down the aircraft and soon. Armed with suppressed Sten guns, they quietly advanced through the fog. Using the bad weather to their advantage, they were able to slip right between the sentries posted to guard the aircraft. -

Living Under Drones Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians from US Drone Practices in Pakistan

Fall 08 September 2012 Living Under Drones Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians From US Drone Practices in Pakistan International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic Stanford Law School Global Justice Clinic http://livingunderdrones.org/ NYU School of Law Cover Photo: Roof of the home of Faheem Qureshi, a then 14-year old victim of a January 23, 2009 drone strike (the first during President Obama’s administration), in Zeraki, North Waziristan, Pakistan. Photo supplied by Faheem Qureshi to our research team. Suggested Citation: INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION CLINIC (STANFORD LAW SCHOOL) AND GLOBAL JUSTICE CLINIC (NYU SCHOOL OF LAW), LIVING UNDER DRONES: DEATH, INJURY, AND TRAUMA TO CIVILIANS FROM US DRONE PRACTICES IN PAKISTAN (September, 2012) TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I ABOUT THE AUTHORS III EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS V INTRODUCTION 1 METHODOLOGY 2 CHALLENGES 4 CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT 7 DRONES: AN OVERVIEW 8 DRONES AND TARGETED KILLING AS A RESPONSE TO 9/11 10 PRESIDENT OBAMA’S ESCALATION OF THE DRONE PROGRAM 12 “PERSONALITY STRIKES” AND SO-CALLED “SIGNATURE STRIKES” 12 WHO MAKES THE CALL? 13 PAKISTAN’S DIVIDED ROLE 15 CONFLICT, ARMED NON-STATE GROUPS, AND MILITARY FORCES IN NORTHWEST PAKISTAN 17 UNDERSTANDING THE TARGET: FATA IN CONTEXT 20 PASHTUN CULTURE AND SOCIAL NORMS 22 GOVERNANCE 23 ECONOMY AND HOUSEHOLDS 25 ACCESSING FATA 26 CHAPTER 2: NUMBERS 29 TERMINOLOGY 30 UNDERREPORTING OF CIVILIAN CASUALTIES BY US GOVERNMENT SOURCES 32 CONFLICTING MEDIA REPORTS 35 OTHER CONSIDERATIONS -

Glossary of Terms

GLOSSARY OF TERMS AC-130 SPECTRE: A ground support aircraft used by the U.S. military, based on the C-130 cargo plane. AC-130s are armed with a 105mm howitzer, 40mm cannons, and 7.62mm miniguns, and are considered the premier close air support weapon of the U.S. arsenal. Accuracy International: A British company producing high-quality preci- sion rifes, often used for military sniper applications. ACOG: Advanced Combat Optical Gunsight. A magnifed optical sight designed for use on rifes and carbines made by Trijicon. Te ACOG is popular among U.S. forces as it provides both magnifcation and an illuminated reticle that provides aiming points for various target ranges. AQ: Al-Qaeda. Meaning “the Base” in Arabic. A radical Islamic terrorist organization once led by Osama bin Laden. AQI: Al-Qaeda in Iraq. An Al-Qaeda-afliated Sunni insurgent group that was active against U.S. forces. Elements of AQI eventually evolved into ISIS. AT-4: Tube-launched 84mm anti-armor rocket produced in Sweden and used by U.S. forces since the 1980s. Te AT-4 is a throwaway weapon: after it is fred, the tube is discarded. ATF/BATFE: Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. A federal law enforcement agency, formally part of the Department of 393 1p_Carr_TerminalList_ds.indd 393 8/22/17 1:07 PM 394 GLOSSARY OF TERMS the Treasury, that doesn’t seem overly concerned with alcohol or to- bacco. ATPIAL: Advanced Target Pointer/Illuminator Aiming Laser. A weapon- mounted device that emits both visible and infrared target designa- tors for use with or without night observation devices. -

Woman As a Category / New Woman Hybridity

WiN: The EAAS Women’s Network Journal Issue 1 (2018) The American Woman Warrior: A Transnational Feminist Look at War, Imperialism, and Gender Agnieszka Soltysik Monnet ABSTRACT: This article examines the issue of torture and spectatorship in the film Zero Dark Thirty through the question of how it deploys gender ideologically and rhetorically to mediate and frame the violence it represents. It begins with the controversy the film provoked but focuses specifically on the movie’s representational and aesthetic techniques, especially its self-awareness about being a film about watching torture, and how it positions its audience in relation to these scenes. Issues of spectator identification, sympathy, interpellation, affect (for example, shame) and genre are explored. The fact that the main protagonist of the film is a woman is a key dimension of the cultural work of the film. I argue that the use of a female protagonist in this film is part of a larger trend in which the discourse of feminism is appropriated for politically conservative and antifeminist ends, here the tacit justification of the legally murky world of black sites and ‘enhanced interrogation techniques.’ KEYWORDS: gender; women’s studies; torture; war on terror; Abu Ghraib; spectatorship; neoliberalism; Angela McRobbie; Some of you will recognize my title as alluding to Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior (1975), a fictionalized autobiography in which she evokes the fifth-century Chinese legend of a girl who disguises herself as a man in order to go to war in the place of her frail old father. Kingston’s use of this legend is credited with having popularized the story in the United States and paved the way for the 1998 Disney adaptation. -

Richard Marcinko (B. 1940) by Delson Ong

Personality Profile 72 Richard Marcinko (b. 1940) by Delson Ong INTRODUCTION In the eyes of the public, the life was hard,’ was how Marcinko United States (US) Navy’s Sea, Air described his childhood.2 Shortly and Land Teams, commonly known before attending high school, the as the Navy SEALs, are a group family moved to New Brunswick, of elite individuals that have New Jersey, where he attended 3 accomplished incredible feats. Of Admiral Farragut Academy. His parents, however, split up the many Special Forces teams, during his high school years, and one of them is responsible for the Marcinko dropped out of high death of the founder of Al-Qaeda, school later that year in 1958. Osama bin Laden—SEAL Team Six. Many people would give the “Change hurts. It makes people Feeling that his life could credit to SEAL Team Six, but let insecure, confused, and angry. potentially spiral down to us not forget the man behind the People want things to be the meaninglessness, young Marcinko same as they have always been, scenes, the brilliant individual decided to take matters into because that makes life easier. who singlehandedly put together his own hands. A coincidental But, if you are a leader, you this special team. This person cannot let your people hang on encounter with US Marines to the past.” is none other than retired US inspired Marcinko to enlist. His Navy SEAL commander, Richard - Retired US Navy SEAL first attempt at enlisting was Commander Richard Marcinko1 Marcinko. unsuccessful, as the Marine Recruiter told him to finish high EARLY LIFE school first before he could Richard Marcinko was born on apply. -

Inconvenient Truths

Inconvenient Truths Moral Challenges to Combat Leadership Dr. George R. Lucas, Jr. Stockdale Center for Ethical Leadership U.S. Naval Academy (Annapolis) 2 20th Annual Joseph Reich, Sr. Memorial Lecture U.S. Air Force Academy (Colorado Springs) November 7, 2007 “Inconvenient Truths” -Moral Challenges to Combat Leadership in the New Millennium- G. R. Lucas U.S. Naval Academy (Annapolis) General Born, General & Mrs. Wakin, Mr. Joseph Reich, Jr and members of the Reich family, honored guests, and most of all, to the members of the Cadet Wing of the USAFA in attendance here tonight: good evening, and thank you for inviting me to be with you. I represent an organization at the Naval Academy, the Stockdale Center for Ethical Leadership. Don’t be put off that our Center is named after “some Navy guy.” In fact, Vice Admiral Stockdale was – as many of you will also one day be – an accomplished aviator and combat leader. He was, as you no doubt also know, a decorated war hero, including the award of the Congressional Medal of Honor. In his many writings, and in a book with an intriguing title, Philosophical Reflections of a Fighter Pilot, Admiral Stockdale taught, in essence, that the true combat 3 leader and warrior is a teacher, a steward, a jurist, a moralist, and. a philosopher. A “Combat Leader” is . • A Teacher • A Steward •A Jurist • A Moralist • A Philosopher We might pause to reflect upon what Stockdale meant by each of these terms. But regardless of the meaning associated with each, I suspect that this unusual list of traits appears nowhere else in the leadership material you have both studied and learned by example during your time at the Air Force Academy. -

The Pope Dalton Fury

SMALL WARS JOURNAL smallwarsjournal.com The Pope Dalton Fury Behind his back we referred to him simply as SAM or Stan the Man. Always with reverence and respect of course. Later on, about the time he started to wear shiny silver stars, we started to refer to him as The Pope. LTG Stanley McChrystal’s meteoric rise through the ranks is no surprise to anyone that has ever had the opportunity to work for or with him. I was fortunate, from a subordinate officer perspective, on numerous occasions. Few know the facts just yet as to why GEN McKeirnan was moved out of command in Afghanistan. Regardless of the reasons, and I’m certainly not read on to the scuttlebutt, I do know that America’s interests, America’s warriors, and America’s mission in Afghanistan couldn’t be in better hands under LTG McChrystal. My biggest concern is that I hope the senior officers in Afghanistan soon to be under LTG McChrystal’s command are well rested. I served as a staff officer under McChrystal in the late 90’s before leaving for 1st SFOD-D. My Ranger peers and I had a unique opportunity to see the good and the bad in the 1976 West Point graduate. I think if McChrystal were wounded on the battlefield, he would bleed red, black, and white – the official colors of the 75th Ranger Regiment. He is 110% US Army Ranger, rising to become the 10th Regimental Commander in the late 90’s, and still sports the physique to prove it. Even with a bum back and likely deteriorating knees after a career of road marching and jumping out of planes he doesn’t recognize the human pause button. -

Självständigt Arbete (15 Hp)

Namn Engström, Joel 2021-05-14 Kurs Självständigt arbete (15 hp) Författare Program/Kurs Engström, Joel OP SA 18-21 Handledare Antal ord: 11986 Mariam Bjarnesen Beteckning Kurskod 1OP415 A LONE SEAL – WHAT FAILURE CAN TELL US. ABSTRACT: Special operations are conducted more than ever in modern warfare. Since the 1980s they have developed and grown in numbers. But with more attempts of operations and bigger numbers, comes failures. One of these failures is operation Red Wings where a unit of US Navy SEALs at- tempted a recognisance and raid operation in the Hindu Kush. The purpose of this paper was to see how that failure could be analysed from an existing theory of Special operations. This was to ensure that other failures can be avoided but mainly to understand what really happened on that mountain in 2005. The method used was a case study of a single case to give an answer with quality and depth. The study found that Mcravens theory and principles of how to succeed a special operation was not applied during the operation. The case of operation Red Wings showed remarkable valour and motivation, but also lacked severely when it came to simplicity, surprise, and speed. Nyckelord: T.ex.: Specialoperationer, McRaven, Operation Red Wings, Specialförband. Sida 1 av 41 Namn Engström, Joel 2021-05-14 Kurs Innehållsförteckning 1. INLEDNING ...................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 PROBLEMFORMULERING ..............................................................................................................