Finitely Big Numbers Name______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

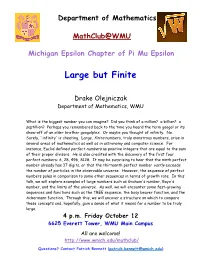

Large but Finite

Department of Mathematics MathClub@WMU Michigan Epsilon Chapter of Pi Mu Epsilon Large but Finite Drake Olejniczak Department of Mathematics, WMU What is the biggest number you can imagine? Did you think of a million? a billion? a septillion? Perhaps you remembered back to the time you heard the term googol or its show-off of an older brother googolplex. Or maybe you thought of infinity. No. Surely, `infinity' is cheating. Large, finite numbers, truly monstrous numbers, arise in several areas of mathematics as well as in astronomy and computer science. For instance, Euclid defined perfect numbers as positive integers that are equal to the sum of their proper divisors. He is also credited with the discovery of the first four perfect numbers: 6, 28, 496, 8128. It may be surprising to hear that the ninth perfect number already has 37 digits, or that the thirteenth perfect number vastly exceeds the number of particles in the observable universe. However, the sequence of perfect numbers pales in comparison to some other sequences in terms of growth rate. In this talk, we will explore examples of large numbers such as Graham's number, Rayo's number, and the limits of the universe. As well, we will encounter some fast-growing sequences and functions such as the TREE sequence, the busy beaver function, and the Ackermann function. Through this, we will uncover a structure on which to compare these concepts and, hopefully, gain a sense of what it means for a number to be truly large. 4 p.m. Friday October 12 6625 Everett Tower, WMU Main Campus All are welcome! http://www.wmich.edu/mathclub/ Questions? Contact Patrick Bennett ([email protected]) . -

Lesson 2: the Multiplication of Polynomials

NYS COMMON CORE MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM Lesson 2 M1 ALGEBRA II Lesson 2: The Multiplication of Polynomials Student Outcomes . Students develop the distributive property for application to polynomial multiplication. Students connect multiplication of polynomials with multiplication of multi-digit integers. Lesson Notes This lesson begins to address standards A-SSE.A.2 and A-APR.C.4 directly and provides opportunities for students to practice MP.7 and MP.8. The work is scaffolded to allow students to discern patterns in repeated calculations, leading to some general polynomial identities that are explored further in the remaining lessons of this module. As in the last lesson, if students struggle with this lesson, they may need to review concepts covered in previous grades, such as: The connection between area properties and the distributive property: Grade 7, Module 6, Lesson 21. Introduction to the table method of multiplying polynomials: Algebra I, Module 1, Lesson 9. Multiplying polynomials (in the context of quadratics): Algebra I, Module 4, Lessons 1 and 2. Since division is the inverse operation of multiplication, it is important to make sure that your students understand how to multiply polynomials before moving on to division of polynomials in Lesson 3 of this module. In Lesson 3, division is explored using the reverse tabular method, so it is important for students to work through the table diagrams in this lesson to prepare them for the upcoming work. There continues to be a sharp distinction in this curriculum between justification and proof, such as justifying the identity (푎 + 푏)2 = 푎2 + 2푎푏 + 푏 using area properties and proving the identity using the distributive property. -

The Infinity Theorem Is Presented Stating That There Is at Least One Multivalued Series That Diverge to Infinity and Converge to Infinite Finite Values

Open Journal of Mathematics and Physics | Volume 2, Article 75, 2020 | ISSN: 2674-5747 https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/9zm6b | published: 4 Feb 2020 | https://ojmp.wordpress.com CX [microresearch] Diamond Open Access The infinity theorem Open Mathematics Collaboration∗† March 19, 2020 Abstract The infinity theorem is presented stating that there is at least one multivalued series that diverge to infinity and converge to infinite finite values. keywords: multivalued series, infinity theorem, infinite Introduction 1. 1, 2, 3, ..., ∞ 2. N =x{ N 1, 2,∞3,}... ∞ > ∈ = { } The infinity theorem 3. Theorem: There exists at least one divergent series that diverge to infinity and converge to infinite finite values. ∗All authors with their affiliations appear at the end of this paper. †Corresponding author: [email protected] | Join the Open Mathematics Collaboration 1 Proof 1 4. S 1 1 1 1 1 1 ... 2 [1] = − + − + − + = (a) 5. Sn 1 1 1 ... 1 has n terms. 6. S = lim+n + S+n + 7. A+ft=er app→ly∞ing the limit in (6), we have S 1 1 1 ... + 8. From (4) and (7), S S 2 = 0 + 2 + 0 + 2 ... 1 + 9. S 2 2 1 1 1 .+.. = + + + + + + 1 10. Fro+m (=7) (and+ (9+), S+ )2 2S . + +1 11. Using (6) in (10), limn+ =Sn 2 2 limn Sn. 1 →∞ →∞ 12. limn Sn 2 + = →∞ 1 13. From (6) a=nd (12), S 2. + 1 14. From (7) and (13), S = 1 1 1 ... 2. + = + + + = (b) 15. S 1 1 1 1 1 ... + 1 16. S =0 +1 +1 +1 +1 +1 1 .. -

The Modal Logic of Potential Infinity, with an Application to Free Choice

The Modal Logic of Potential Infinity, With an Application to Free Choice Sequences Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ethan Brauer, B.A. ∼6 6 Graduate Program in Philosophy The Ohio State University 2020 Dissertation Committee: Professor Stewart Shapiro, Co-adviser Professor Neil Tennant, Co-adviser Professor Chris Miller Professor Chris Pincock c Ethan Brauer, 2020 Abstract This dissertation is a study of potential infinity in mathematics and its contrast with actual infinity. Roughly, an actual infinity is a completed infinite totality. By contrast, a collection is potentially infinite when it is possible to expand it beyond any finite limit, despite not being a completed, actual infinite totality. The concept of potential infinity thus involves a notion of possibility. On this basis, recent progress has been made in giving an account of potential infinity using the resources of modal logic. Part I of this dissertation studies what the right modal logic is for reasoning about potential infinity. I begin Part I by rehearsing an argument|which is due to Linnebo and which I partially endorse|that the right modal logic is S4.2. Under this assumption, Linnebo has shown that a natural translation of non-modal first-order logic into modal first- order logic is sound and faithful. I argue that for the philosophical purposes at stake, the modal logic in question should be free and extend Linnebo's result to this setting. I then identify a limitation to the argument for S4.2 being the right modal logic for potential infinity. -

Cantor on Infinity in Nature, Number, and the Divine Mind

Cantor on Infinity in Nature, Number, and the Divine Mind Anne Newstead Abstract. The mathematician Georg Cantor strongly believed in the existence of actually infinite numbers and sets. Cantor’s “actualism” went against the Aristote- lian tradition in metaphysics and mathematics. Under the pressures to defend his theory, his metaphysics changed from Spinozistic monism to Leibnizian volunta- rist dualism. The factor motivating this change was two-fold: the desire to avoid antinomies associated with the notion of a universal collection and the desire to avoid the heresy of necessitarian pantheism. We document the changes in Can- tor’s thought with reference to his main philosophical-mathematical treatise, the Grundlagen (1883) as well as with reference to his article, “Über die verschiedenen Standpunkte in bezug auf das aktuelle Unendliche” (“Concerning Various Perspec- tives on the Actual Infinite”) (1885). I. he Philosophical Reception of Cantor’s Ideas. Georg Cantor’s dis- covery of transfinite numbers was revolutionary. Bertrand Russell Tdescribed it thus: The mathematical theory of infinity may almost be said to begin with Cantor. The infinitesimal Calculus, though it cannot wholly dispense with infinity, has as few dealings with it as possible, and contrives to hide it away before facing the world Cantor has abandoned this cowardly policy, and has brought the skeleton out of its cupboard. He has been emboldened on this course by denying that it is a skeleton. Indeed, like many other skeletons, it was wholly dependent on its cupboard, and vanished in the light of day.1 1Bertrand Russell, The Principles of Mathematics (London: Routledge, 1992 [1903]), 304. -

Chapter 2. Multiplication and Division of Whole Numbers in the Last Chapter You Saw That Addition and Subtraction Were Inverse Mathematical Operations

Chapter 2. Multiplication and Division of Whole Numbers In the last chapter you saw that addition and subtraction were inverse mathematical operations. For example, a pay raise of 50 cents an hour is the opposite of a 50 cents an hour pay cut. When you have completed this chapter, you’ll understand that multiplication and division are also inverse math- ematical operations. 2.1 Multiplication with Whole Numbers The Multiplication Table Learning the multiplication table shown below is a basic skill that must be mastered. Do you have to memorize this table? Yes! Can’t you just use a calculator? No! You must know this table by heart to be able to multiply numbers, to do division, and to do algebra. To be blunt, until you memorize this entire table, you won’t be able to progress further than this page. MULTIPLICATION TABLE ϫ 012 345 67 89101112 0 000 000LEARNING 00 000 00 1 012 345 67 89101112 2 024 681012Copy14 16 18 20 22 24 3 036 9121518212427303336 4 0481216 20 24 28 32 36 40 44 48 5051015202530354045505560 6061218243036424854606672Distribute 7071421283542495663707784 8081624324048566472808896 90918273HAWKESReview645546372819099108 10 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110 120 ©11 0 11 22 33 44NOT 55 66 77 88 99 110 121 132 12 0 12 24 36 48 60 72 84 96 108 120 132 144 Do Let’s get a couple of things out of the way. First, any number times 0 is 0. When we multiply two numbers, we call our answer the product of those two numbers. -

Grade 7/8 Math Circles the Scale of Numbers Introduction

Faculty of Mathematics Centre for Education in Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1 Mathematics and Computing Grade 7/8 Math Circles November 21/22/23, 2017 The Scale of Numbers Introduction Last week we quickly took a look at scientific notation, which is one way we can write down really big numbers. We can also use scientific notation to write very small numbers. 1 × 103 = 1; 000 1 × 102 = 100 1 × 101 = 10 1 × 100 = 1 1 × 10−1 = 0:1 1 × 10−2 = 0:01 1 × 10−3 = 0:001 As you can see above, every time the value of the exponent decreases, the number gets smaller by a factor of 10. This pattern continues even into negative exponent values! Another way of picturing negative exponents is as a division by a positive exponent. 1 10−6 = = 0:000001 106 In this lesson we will be looking at some famous, interesting, or important small numbers, and begin slowly working our way up to the biggest numbers ever used in mathematics! Obviously we can come up with any arbitrary number that is either extremely small or extremely large, but the purpose of this lesson is to only look at numbers with some kind of mathematical or scientific significance. 1 Extremely Small Numbers 1. Zero • Zero or `0' is the number that represents nothingness. It is the number with the smallest magnitude. • Zero only began being used as a number around the year 500. Before this, ancient mathematicians struggled with the concept of `nothing' being `something'. 2. Planck's Constant This is the smallest number that we will be looking at today other than zero. -

Maths Secrets of Simpsons Revealed in New Book

MONDAY 7 OCTOBER 2013 WWW.THEDAY.CO.UK Maths secrets of Simpsons revealed in new book The most successful TV show of all time is written by a team of brilliant ‘mathletes’, says writer Simon Singh, and full of obscure mathematical jokes. Can numbers really be all that funny? MATHEMATICS Nerd hero: The smartest girl in Springfield was created by a team of maths wizards. he world’s most popular cartoon a perfect number, a narcissistic number insist that their love of maths contrib- family has a secret: their lines are and a Mersenne Prime. utes directly to the more obvious humour written by a team of expert mathema- Another of these maths jokes – a black- that has made the show such a hit. Turn- Tticians – former ‘mathletes’ who are board showing 398712 + 436512 = 447212 ing intuitions about comedy into concrete as happy solving differential equa- – sent shivers down Simon Singh’s spine. jokes is like wrestling mathematical tions as crafting jokes. ‘I was so shocked,’ he writes, ‘I almost hunches into proofs and formulas. Comedy Now, science writer Simon Singh has snapped my slide rule.’ The numbers are and maths, says Cohen, are both explora- revealed The Simpsons’ secret math- a fake exception to a famous mathemati- tions into the unknown. ematical formula in a new book*. He cal rule known as Fermat’s Last Theorem. combed through hundreds of episodes One episode from 1990 features a Mathletes and trawled obscure internet forums to teacher making a maths joke to a class of Can maths really be funny? There are many discover that behind the show’s comic brilliant students in which Bart Simpson who will think comparing jokes to equa- exterior lies a hidden core of advanced has been accidentally included. -

Power Towers and the Tetration of Numbers

POWER TOWERS AND THE TETRATION OF NUMBERS Several years ago while constructing our newly found hexagonal integer spiral graph for prime numbers we came across the sequence- i S {i,i i ,i i ,...}, Plotting the points of this converging sequence out to the infinite term produces the interesting three prong spiral converging toward a single point in the complex plane as shown in the following graph- An inspection of the terms indicate that they are generated by the iteration- z[n 1] i z[n] subject to z[0] 0 As n gets very large we have z[]=Z=+i, where =exp(-/2)cos(/2) and =exp(-/2)sin(/2). Solving we find – Z=z[]=0.4382829366 + i 0.3605924718 It is the purpose of the present article to generalize the above result to any complex number z=a+ib by looking at the general iterative form- z[n+1]=(a+ib)z[n] subject to z[0]=1 Here N=a+ib with a and b being real numbers which are not necessarily integers. Such an iteration represents essentially a tetration of the number N. That is, its value up through the nth iteration, produces the power tower- Z Z n Z Z Z with n-1 zs in the exponents Thus- 22 4 2 22 216 65536 Note that the evaluation of the powers is from the top down and so is not equivalent to the bottom up operation 44=256. Also it is clear that the sequence {1 2,2 2,3 2,4 2,...}diverges very rapidly unlike the earlier case {1i,2 i,3i,4i,...} which clearly converges. -

A Child Thinking About Infinity

A Child Thinking About Infinity David Tall Mathematics Education Research Centre University of Warwick COVENTRY CV4 7AL Young children’s thinking about infinity can be fascinating stories of extrapolation and imagination. To capture the development of an individual’s thinking requires being in the right place at the right time. When my youngest son Nic (then aged seven) spoke to me for the first time about infinity, I was fortunate to be able to tape-record the conversation for later reflection on what was happening. It proved to be a fascinating document in which he first treated infinity as a very large number and used his intuitions to think about various arithmetic operations on infinity. He also happened to know about “minus numbers” from earlier experiences with temperatures in centigrade. It was thus possible to ask him not only about arithmetic with infinity, but also about “minus infinity”. The responses were thought-provoking and amazing in their coherent relationships to his other knowledge. My research in studying infinite concepts in older students showed me that their ideas were influenced by their prior experiences. Almost always the notion of “limit” in some dynamic sense was met before the notion of one to one correspondences between infinite sets. Thus notions of “variable size” had become part of their intuition that clashed with the notion of infinite cardinals. For instance, Tall (1980) reported a student who considered that the limit of n2/n! was zero because the top is a “smaller infinity” than the bottom. It suddenly occurred to me that perhaps I could introduce Nic to the concept of cardinal infinity to see what this did to his intuitions. -

WRITING and READING NUMBERS in ENGLISH 1. Number in English 2

WRITING AND READING NUMBERS IN ENGLISH 1. Number in English 2. Large Numbers 3. Decimals 4. Fractions 5. Power / Exponents 6. Dates 7. Important Numerical expressions 1. NUMBERS IN ENGLISH Cardinal numbers (one, two, three, etc.) are adjectives referring to quantity, and the ordinal numbers (first, second, third, etc.) refer to distribution. Number Cardinal Ordinal In numbers 1 one First 1st 2 two second 2nd 3 three third 3rd 4 four fourth 4th 5 five fifth 5th 6 six sixth 6th 7 seven seventh 7th 8 eight eighth 8th 9 nine ninth 9th 10 ten tenth 10th 11 eleven eleventh 11th 12 twelve twelfth 12th 13 thirteen thirteenth 13th 14 fourteen fourteenth 14th 15 fifteen fifteenth 15th 16 sixteen sixteenth 16th 17 seventeen seventeenth 17th 18 eighteen eighteenth 18th 19 nineteen nineteenth 19th 20 twenty twentieth 20th 21 twenty-one twenty-first 21st 22 twenty-two twenty-second 22nd 23 twenty-three twenty-third 23rd 1 24 twenty-four twenty-fourth 24th 25 twenty-five twenty-fifth 25th 26 twenty-six twenty-sixth 26th 27 twenty-seven twenty-seventh 27th 28 twenty-eight twenty-eighth 28th 29 twenty-nine twenty-ninth 29th 30 thirty thirtieth 30th st 31 thirty-one thirty-first 31 40 forty fortieth 40th 50 fifty fiftieth 50th 60 sixty sixtieth 60th th 70 seventy seventieth 70 th 80 eighty eightieth 80 90 ninety ninetieth 90th 100 one hundred hundredth 100th 500 five hundred five hundredth 500th 1,000 One/ a thousandth 1000th thousand one thousand one thousand five 1500th 1,500 five hundred, hundredth or fifteen hundred 100,000 one hundred hundred thousandth 100,000th thousand 1,000,000 one million millionth 1,000,000 ◊◊ Click on the links below to practice your numbers: http://www.manythings.org/wbg/numbers-jw.html https://www.englisch-hilfen.de/en/exercises/numbers/index.php 2 We don't normally write numbers with words, but it's possible to do this. -

Parameter Free Induction and Provably Total Computable Functions

Parameter free induction and provably total computable functions Lev D. Beklemishev∗ Steklov Mathematical Institute Gubkina 8, 117966 Moscow, Russia e-mail: [email protected] November 20, 1997 Abstract We give a precise characterization of parameter free Σn and Πn in- − − duction schemata, IΣn and IΠn , in terms of reflection principles. This I − I − allows us to show that Πn+1 is conservative over Σn w.r.t. boolean com- binations of Σn+1 sentences, for n ≥ 1. In particular, we give a positive I − answer to a question, whether the provably recursive functions of Π2 are exactly the primitive recursive ones. We also characterize the provably − recursive functions of theories of the form IΣn + IΠn+1 in terms of the fast growing hierarchy. For n = 1 the corresponding class coincides with the doubly-recursive functions of Peter. We also obtain sharp results on the strength of bounded number of instances of parameter free induction in terms of iterated reflection. Keywords: parameter free induction, provably recursive functions, re- flection principles, fast growing hierarchy Mathematics Subject Classification: 03F30, 03D20 1 Introduction In this paper we shall deal with the first order theories containing Kalmar ele- mentary arithmetic EA or, equivalently, I∆0 + Exp (cf. [11]). We are interested in the general question how various ways of formal reasoning correspond to models of computation. This kind of analysis is traditionally based on the con- cept of provably total recursive function (p.t.r.f.) of a theory. Given a theory T containing EA, a function f(~x) is called provably total recursive in T , iff there is a Σ1 formula φ(~x, y), sometimes called specification, that defines the graph of f in the standard model of arithmetic and such that T ⊢ ∀~x∃!y φ(~x, y).