19-H-1753-CE -And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

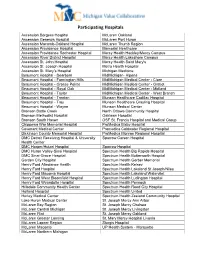

Participating Hospitals

Participating Hospitals Ascension Borgess Hospital McLaren Oakland Ascension Genesys Hospital McLaren Port Huron Ascension Macomb-Oakland Hospital McLaren Thumb Region Ascension Providence Hospital Memorial Healthcare Ascension Providence Rochester Hospital Mercy Health Hackley/Mercy Campus Ascension River District Hospital Mercy Health Lakeshore Campus Ascension St. John Hospital Mercy Health Saint Mary's Ascension St. Joseph Hospital Metro Health Hospital Ascension St. Mary’s Hospital Michigan Medicine Beaumont Hospital - Dearborn MidMichigan- Alpena Beaumont Hospital - Farmington Hills MidMichigan Medical Center - Clare Beaumont Hospital - Grosse Pointe MidMichigan Medical Center - Gratiot Beaumont Hospital - Royal Oak MidMichigan Medical Center - Midland Beaumont Hospital - Taylor MidMichigan Medical Center - West Branch Beaumont Hospital - Trenton Munson Healthcare Cadillac Hospital Beaumont Hospital - Troy Munson Healthcare Grayling Hospital Beaumont Hospital - Wayne Munson Medical Center Bronson Battle Creek North Ottawa Community Hospital Bronson Methodist Hospital Oaklawn Hospital Bronson South Haven OSF St. Francis Hospital and Medical Group Chippewa War Memorial Hospital ProMedica Bixby Hospital Covenant Medical Center Promedica Coldwater Regional Hospital Dickinson County Memorial Hospital ProMedica Monroe Regional Hospital DMC Detroit Receiving Hospital & University Sparrow Carson Hospital Health Center DMC Harper/Hutzel Hospital Sparrow Hospital DMC Huron Valley-Sinai Hospital Spectrum Health Big Rapids Hospital DMC Sinai-Grace -

Hospitals Participating in MOSAIC, by County and Region, 2015-2024

Ascension Genesys Hospital (Genesee) Aspirus Ironwood Hospital (Gogebic) Hospitals Participating in MiSP 2021-2024 Ascension Macomb Oakland Hospital (Macomb) Aspirus Iron River Hospital (Iron) Aspirus Keweenaw Hospital (Keweenaw) Ascension Providence Hospital, Novi Campus (Oakland) Aspirus Ontonagon Hospital (Ontonagon) Ascension Providence Rochester Hospital (Oakland) Ascension Providence Hospital, Southfield (Oakland) Ascension St. Mary’s Hospital (Saginaw) Covenant Health Care (Saginaw) Ascension St. John Hospital (Wayne) Deckerville Community Hospital (Sanilac) Detroit Receiving Hospital (Wayne) Marlette Regional Hospital (Sanilac) Henry Ford Hospital (Wayne) McKenzie Health System (Sanilac) Henry Ford Macomb Hospital (Macomb) McLaren Bay Regional Medical Center (Bay) Henry Ford West Bloomfield Hospital (Oakland) Henry Ford Wyandotte Hospital (Wayne) Mercy Health Saint Mary’s Hospital (Kent) Hurley Medical Center (Genesee) Mercy Health Mercy Campus (Muskegon) Huron Valley-Sinai Hospital (Oakland) Metro Health Hospital (Kent) McLaren Greater Medical Center (Ingham) Spectrum Health Blodgett Hospital (Kent) McLaren Lapeer Region Hospital (Lapeer) Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital (Kent) McLaren Macomb Hospital (Macomb) McLaren Oakland Medical Center (Oakland) McLaren Northern Michigan Hospital (Emmet) McLaren Port Huron Hospital (St Clair) Munson Medical Center (Grand Traverse) McLaren Regional Medical Center (Genesee) Ascension Borgess Hospital (Kalamazoo) Michigan Medicine Hospital (Washtenaw) Bronson Methodist Hospital (Kalamazoo) St Joseph Mercy Hospital-Ann Arbor Hospital ProMedica Bixby Medical Center (Lenawee) Oaklawn Hospital (Calhoun) St Joseph Mercy Hospital-Chelsea Hospital (Washtenaw) ProMedica Herrick Medical Center (Lenawee) Spectrum Health Lakeland Hospital (St Joseph) St. Joseph Mercy Oakland Hospital (Oakland) ProMedica Monroe Regional Hospital (Monroe) Red dashed box indicates hospitals participating in the MOSAIC Transition of Care. St. Mary Mercy Hospital (Wayne) Sparrow Hospital (Ingham) . -

Flint Fights Back, Environmental Justice And

Thank you for your purchase of Flint Fights Back. We bet you can’t wait to get reading! By purchasing this book through The MIT Press, you are given special privileges that you don’t typically get through in-device purchases. For instance, we don’t lock you down to any one device, so if you want to read it on another device you own, please feel free to do so! This book belongs to: [email protected] With that being said, this book is yours to read and it’s registered to you alone — see how we’ve embedded your email address to it? This message serves as a reminder that transferring digital files such as this book to third parties is prohibited by international copyright law. We hope you enjoy your new book! Flint Fights Back Urban and Industrial Environments Series editor: Robert Gottlieb, Henry R. Luce Professor of Urban and Environmental Policy, Occidental College For a complete list of books published in this series, please see the back of the book. Flint Fights Back Environmental Justice and Democracy in the Flint Water Crisis Benjamin J. Pauli The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England © 2019 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Stone Serif by Westchester Publishing Services. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Pauli, Benjamin J., author. -

Community Health Needs Assessment 2019

FLINT & GENESEE COUNTY, MICHIGAN COMMUNITY HEALTH NEEDS ASSESSMENT REPORT 2019 COMMUNITY HEALTH NEEDS ASSESSMENT REPORT a TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 I. INTRODUCTION 5 Community Health Needs Assessment Population 5 Flint / Genesee County Demographics 5 Organizations Completing the CHNA 7 II. COMMUNITY HEALTH NEEDS ASSESSMENT INFRASTRUCTURE & PARTNERSHIPS 11 Partnerships 11 III. DATA COLLECTION & ANALYSIS 13 Data Sources 13 Indicators and Data Measures 14 Methods and Approach 17 Factors that Affect Health 18 IV. COMMUNITY HEALTH NEEDS IDENTIFIED & ASSESSMENT PRIORITIES 19 Social Determinants of Health (including Housing, Education, Employment, Food Insecurity, Safety, and Poverty) 20 Substance Use (with emphasis on Opioid Misuse and Addiction) 31 Child Health & Development 34 Mental Health 36 Obesity & Health Behaviors 38 Safe and Affordable Drinking Water 40 Healthcare Access 42 Chronic Disease Burden 45 Effective Care Delivery for an Aging Population 47 Infant Maternal Health 49 Sexual Health 51 Health Equity 52 2019 CHNA Survey Highlights 54 APPENDIX A: EVALUATION OF IMPACT FROM 2016 CHNA IMPLEMENTATION 57 Part 1: 2016-2018 CHNA Implementation Plan Accomplishments conducted via Greater Flint Health Coalition in partnership with Genesys, Hurley, and McLaren Genesee Community Health Access Program 57 State Innovation Model (SIM) Clinical Community Linkage Initiative 58 Commit to Fit 60 Children’s Oral Health Task Force 61 Connecting Kids to Coverage 62 Flint Healthcare Employment Opportunities Program 62 COMMUNITY HEALTH NEEDS -

Comprehensive Annual Financial Report CIT Y of FLINT MICHIGAN

Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2018 MICHIGAN CITY OF FLINT OF FLINT CITY City of Flint, Michigan Comprehensive Annual Financial Report For the Year Ended June 30, 2018 Prepared by: Department of Finance and Administration Dawn Steele, Deputy Director of Finance Table of Contents Section Page Introductory Section Letter of Transmittal i GFOA Certificate of Achievement vii Organizational Chart viii List of Elected, Civil Service, and Appointed Officials ix Financial Section 1 Independent Auditors’ Report 1 – 1 2 Management’s Discussion and Analysis 2 – 1 3 Basic Financial Statements Government-wide Financial Statements Statement of Net Position 3 – 1 Statement of Activities 3 – 3 Fund Financial Statements Governmental Funds Balance Sheet 3 – 4 Reconciliation of Fund Balances of Governmental Funds to Net Position of Governmental Activities 3 – 6 Statement of Revenues, Expenditures and Changes in Fund Balances 3 – 7 Reconciliation of the Statement of Revenues, Expenditures and Changes in Fund Balances of Governmental Funds to the Statement of Activities 3 – 9 Section Page 3 Basic Financial Statements Proprietary Funds Statement of Net Position 3 – 10 Statement of Revenues, Expenses and Changes in Fund Net Position 3 – 12 Statement of Cash Flows 3 – 14 Fiduciary Funds Statement of Fiduciary Net Position 3 – 16 Statement of Changes in Fiduciary Net Position 3 – 17 Component Units Combining Statement of Net Position 3 – 18 Combining Statement of Activities 3 – 20 Notes to the Financial Statements 3 – -

Shiawassee County Directory of Services for Seniors and Vulnerable Adults

Shiawassee County Directory of Services for Seniors and Vulnerable Adults • Community at Large • Health Care • Law Enforcement • Social Service Agencies 2020 Shiawassee County Coalition Against Vulnerable Adult Abuse If you or someone you love is age 60 or older, Valley Area Agency on Aging (VAAA) is here to help! VAAA is a non-profitagency that provides valuable resources to seniors and disabled residents of Genesee. Lapeer and Shiawassee counties. VAAA can help with many area services, including: ./ Information and Assistance: Our Information Specialists provide information and resources for the services and programs that are right foryou . .,/ Ml Choice Waiver Program: Designed to help seniors get the services they need while living independently in their own home . .,/ Care Management: A custom plan of care that fosters safe, independent living . ./ KISS Program: The KISS (Keeping Independent Seniors Safe) program provides a daily phone call to ensure the senior is safe, alerting the alternate contact if the senior cannot be reached. MMAP Inc. Medicare Medicaid Assistance _____, ·-- Program (MMAP), State Health Insurance Assistance Program This free service provides information about Medicaid and Medicare, health plans, prescription coverage and more. Trained counselors will answer your questions: (800) 803-7174 or (810) 249-6552 For more information on available programs and services, please call Valley Area Agency on Aging at (810) 239-7671 toll free at (800) 978-6275 Visit our website at www.valleyareaaging.org. FOLLOW VAAA! � rJ e ti Owosso A Wise Choice Owl’s Nest Assisted Living 3837 S. M-52, Owosso 989-277-6427 [email protected] Debbie Smith, RN Owner We Care Assisted Living 3973 W. -

State Federal

Michigan Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs, Hospitals Provider Directory Bureau of Community and Health Systems PROVIDER NAME ADDRESS CITY, STATE, ZIPCODE COUNTY Allegan General Hospital 555 Linn Street Allegan MI 49010 Allegan Ascension Borgess Hospital 1521 Gull Road Kalamazoo MI 49048 Kalamazoo Ascension Borgess Lee Hospital 420 W High St Dowagiac MI 49047 Cass Ascension Borgess Pipp Hospital 411 Naomi Street Plainwell MI 49080 Allegan Ascension Brighton Center For Recovery 12851 Grand River Rd Brighton MI 48116 Livingston Ascension Genesys Hospital One Genesys Parkway Grand Blanc MI 48439 Genesee Ascension Macomb Oakland Hosp-Madison Hghts Campus27351 Dequindre Madison Heights MI 48071 Oakland Ascension Macomb Oakland Hosp-Warren Campus 11800 East Twelve Mile Road Warren MI 48093 Macomb Ascension Providence Hospital 16001 W Nine Mile Rd Southfield MI 48075 Oakland Ascension Providence Rochester Hospital 1101 W University Drive Rochester MI 48307 Oakland Ascension River District Hospital 4100 River Rd East China MI 48054 Saint Clair Ascension St John Hospital 22101 Moross Rd Detroit MI 48236 Wayne Ascension St Joseph Hospital 200 Hemlock Tawas City MI 48764 Iosco Ascension St Mary'S Hospital 800 S Washington Avenue Saginaw MI 48601 Saginaw Ascension Standish Hospital 805 W Cedar St Standish MI 48658 Arenac Aspirus Iron River Hospital & Clinics, Inc 1400 W Ice Lake Road Iron River MI 49935 Iron Aspirus Ironwood Hospital N10561 Grand View Lane Ironwood MI 49938 Gogebic Aspirus Keweenaw Hospital 205 Osceola Laurium MI 49913 -

Community Health Needs Assessment Report 2016

Community Health Needs Assessment Report 2016 Community Health Needs Assessment Subgroup Collaborative activity of the Greater Flint Health Coalition in partnership with Genesys Health System, Hurley Medical Center, and McLaren Flint Commerce Center ● 519 South Saginaw Street, Suite 306 ● Flint, Michigan 48502-1815 Business: 810-232-2228 ● Fax: 810-232-3332 ● E-mail: [email protected] ● www.gfhc.org TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY…………………………………………………………………………….. 3 I. INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Community Health Needs Assessment Population………………………………………… 4 Flint / Genesee County Demographics………………………………………………………. 4 Organizations Completing the CHNA………………………………………………………… 5 II. CHNA INFRASTRUCTURE & PARTNERSHIPS…………………………………………... 9 Partners………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 III. DATA COLLECTION & ANALYSIS…………………………………………………………. 10 Data Sources……………………………………………………………………………………. 10 Methods and Approach………………………………………………………………………… 12 Factors that Affect Health……………………………………………………………………… 13 IV. COMMUNITY HEALTH NEEDS IDENTIFIED & ASSESSMENT PRIORITIES………… 14 1. Access to Clean & Safe Drinking Water……………………………………………….. 14 2. Infant / Child Health & Development…………………………………………………… 15 3. Obesity / Overweight / Healthy Lifestyles…..………………………………………….. 17 4. Effective Care Delivery for an Aging Population……………………………………… 19 5. Mental Health…………………………………………………………………………….. 19 6. Substance Use…………………………………………………………………………… 20 7. Education & Employment……………………………………………………………….. 21 8. Food Insecurity…………………………………………………………………………… 21 -

Bishop International Airport Bishop International Airport

Covering Business in Flint & Genesee May/June 2018 Navigating market conditions Bishop International Airport Member Spotlight Destinations To Travel MTA More than just a bus service TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 10 12 This Issue COVER STORY 6 Bishop Airport delivers for Flint & Genesee (On the cover: Bishop’s passenger terminal.) Departments 10 Member Spotlight 4 Event Calendar Destinations To Travel, at your service 5 From the CEO 14 Chamber in Action 12 Feature Story MTA transforming public transportation 15 New Members 16 Members on the Move 18 Guest Commentary PUBLICATION EDITORIAL INQUIRIES DISTRIBUTION May/June 2018 Editor-in-Chief: Elaine Redd Members are encouraged to send news AND is distributed free of charge to [email protected] about their business—staff changes, Chamber members. Vol. 2 | Issue 3 awards, or expansions—for publication in Managing Editor: Bob Campbell Members on the Move. Send submissions CONTACT [email protected] to Savannah Lee, [email protected]. Flint & Genesee Chamber of Commerce Art & Design: Carol Pongrac The Chamber reserves the right to deny 519 S. Saginaw Street [email protected] and/or edit submissions. Flint, MI 48502 (810) 600-1404 Contributors: Izzi Joseph, DISCLAIMER [email protected] Melissa Burden, Michael Naddeo The Chamber is not responsible for the www.flintandgenesee.org ADVERTISING contents of any advertisement, and all AND is published bi-monthly representations of warranties made by the Flint & Genesee Sales Director: Steven Elkins [email protected] in such advertising are those of the Chamber of Commerce advertiser. No part of this publication ©2018 may be reproduced without written permission of the Chamber. -

Fluoride Varnish Certificates for Medicaid Professionals

December 8, 2017 Michigan Department of Health and Human Services Page 1 of 34 Fluoride Varnish Training Certificates for Medicaid Professionals County: Name: Title: Provider NPI: Agency: Address: Allegan Rik Tooker MD 1154385672 Allegan County Health Dept 3255 122nd Ave. Ste 200 Allegan, MI 49010 Allegan Cassie Plockmeyer NP 1518385129 Allegan Professional Health Services 551 Linn Street Allegan, MI 49010 Allegan Sara Franzen MD 1871735522 Allegan Professional Health Services 551 Linn Street Allegan, MI 49010 Allegan William Davis MD 1629130703 Allegan Professional Health Services 551 Linn Street Allegan, MI 49010 Allegan Tom Saad waiting on cert from MD 1417908930 Borgess Family Medicine & Pediatrics 345 Naomi Street Plainwell, MI 49080 Altarum Allegan, Ottawa Allison Rund MD 1164685608 Spectrum Health Med Group- Holland 588 E. Lakewood Blvd. Holland, MI 49424 Allegan, Ottawa Erin Michelle Walton CPNP-PC, 1669847703 Spectrum Health Med Group- Holland 588 E. Lakewood Blvd. Holland, MI 49424 BSN, RN Allegan, Ottawa Nancy MacDonald MD 1114960150 Spectrum Health Med Group- Holland 588 E. Lakewood Blvd. Holland, MI 49424 Allegan, Ottawa Wendy Pytlak Zink DO 1760450928 Spectrum Health Med Group- Holland 588 E. Lakewood Blvd. Holland, MI 49424 Alpena Christy Werth DO 1750390498 Alpena Medical Arts, P.C. 211 Long Rapids Rd. Alpena, MI 49707 Alpena James Decker MD 1497749576 Alpena Medical Arts, P.C. 211 Long Rapids Rd. Alpena, MI 49707 Alpena Kathleen Phillips NP 1497099667 Alpena Medical Arts, P.C. 211 Long Rapids Rd. Alpena, MI 49707 Alpena Rong Lawson MD 1215116025 Alpena Medical Arts, P.C. 211 Long Rapids Rd. Alpena, MI 49707 Antrim Albert Brown MD 1174516744 Mancelona Family Practice 419 W. -

Community Hospital Network

COMMUNITYMcLaren HOSPITAL DirectCare NETWORK McLaren Health Plan CommunityHospital Network ALLEGAN GENESEEEMMET LAPEERKENT OAKLANDBeaumont Hospital SANILACSHIAWASSEE Allegan General Hospital Hurley Medical Center McLaren Lapeer Region* – Troy Campus Memorial Hospital & AlleganAscension General Hospital McLaren Flint* Northern Michigan Helen DeVos AscensionDMC Huron ValleyProvidence Sinai Hospital Deckerville Healthcare CenterCommunity Ascension Borgess-Pipp Hospital Select Specialty Hospital Flint LIVINGSTON Children’s Hospital Havenwyck Rochester Hospital** Hospital Hospital Borgess-Pipp Hospital GENESEE BrightonSpectrum Hospital** Health AscensionHenry Ford Providence McKenzieTUSCOLA Health System ALPENA GLADWIN Kingswood Hospital** Hills & Dales General Hospital Mid Michigan Medical MidMichiganHurley Medical Medical Center Center MACKINAC Blodgett Hospital Henry Hospital- Ford WestSouthfield McLaren Caro Region ALPENA Center Alpena McLaren Flint MackinacSpectrum Straits Health Health System BloomfieldCampus Hospital SHIAWASSEE Mid Michigan Medical GRAND TRAVERSE Butterworth Hospital AscensionMaplegrove ProvidenceCenter** MemorialVAN BUREN Healthcare ARENAC Munson Medical Center MACOMB McLaren Oakland* Bronson South Haven Hospital Ascension Center-Alpena Standish Hospital GLADWIN AscensionLAPEER Macomb McLaren Hospital-Novi Oakland Campus Clarkston* Hospital GRATIOTMidMichigan McLaren Oakland Hospital Lapeer Region AscensionMcLaren Oakland Macomb Oxford* Oakland WASHTENAW ARENACBARRY MidMichigan Medical Center-Gladwin Medical Center -

June 2015 6 Hurleymc.Com

JUNE 2015 6 HURLEYMC.COM SAVE THE DATE: Hurley Annual Trauma Center Golf Classic Flint Golf Club September 14, 2015 This year’s Trauma Center Golf Classic Ambassador: Jeff Umphrey Jeff and Kathryn Umphrey of Clio started volunteering in Hurley Medical Center’s Burn Unit, the only one in the region comprised of Genesee, Lapeer and Shiawassee Counties, in January, 2015. The couple wanted to give back and provide support to victims, because nearly 30 years ago, Continuing Medical Hurley’s Burn Unit saved Jeff’s life after a nearly fatal, horrific accident. Education (CME) On December 10, 1985, 34-year-old Jeff was working as a body shop mechanic when a gasoline spill would forever change his life. While taking a gas tank out of a car, gas spilled on Jeff and a nearby light bulb. The gas ignited and Jeff caught on fire. After being rushed to Hurley, doctors CALENDAR discovered he suffered third degree burns to 54% of his body, on his chest, abdomen, legs, left arm and hand. Jeff spent 6 weeks at Hurley, 4 of those weeks in a medically induced coma, with continued rehabilitation for several more months. Save the Date: “I had a truly amazing experience at Hurley. I received exceptional care that changed my life. Today, 31st Annual Trauma Center Golf Classic my wife and I volunteer in the very Burn Unit that saved my life. I feel truly blessed Hurley Medical Monday, September 14, 2015 Center was here. Without Hurley, I don’t believe I’d be alive,” adds Umphrey. Flint Golf Club “Hurley Medical Center is proud to be the premier public teaching hospital and the region’s only Level I Adult and Level II Pediatric Trauma Center in the region, caring for critically ill adults and Child & Adolescent Depression children, around the clock.