The Case of Victoria, Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government and Indigenous Australians Exclusionary Values

Government and Indigenous Australians Exclusionary values upheld in Australian Government continue to unjustly prohibit the participation of minority population groups. Indigenous people “are among the most socially excluded in Australia” with only 2.2% of Federal parliament comprised of Aboriginal’s. Additionally, Aboriginal culture and values, “can be hard for non-Indigenous people to understand” but are critical for creating socially inclusive policy. This exclusion from parliament is largely as a result of a “cultural and ethnic default in leadership” and exclusionary values held by Australian parliament. Furthermore, Indigenous values of autonomy, community and respect for elders is not supported by the current structure of government. The lack of cohesion between Western Parliamentary values and Indigenous cultural values has contributed to historically low voter participation and political representation in parliament. Additionally, the historical exclusion, restrictive Western cultural norms and the continuing lack of consideration for the cultural values and unique circumstances of Indigenous Australians, vital to promote equity and remedy problems that exist within Aboriginal communities, continue to be overlooked. Current political processes make it difficult for Indigenous people to have power over decisions made on their behalf to solve issues prevalent in Aboriginal communities. This is largely as “Aboriginal representatives are in a better position to represent Aboriginal people and that existing politicians do not or cannot perform this role.” Deeply “entrenched inequality in Australia” has led to the continuity of traditional Anglo- Australian Parliamentary values, which inherently exclude Indigenous Australians. Additionally, the communication between the White Australian population and the Aboriginal population remains damaged, due to “European contact tend[ing] to undermine Aboriginal laws, society, culture and religion”. -

Epidemics and Pandemics in Victoria: Historical Perspectives

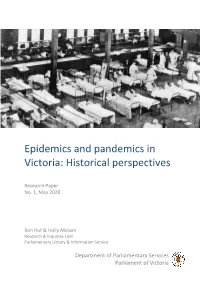

Epidemics and pandemics in Victoria: Historical perspectives Research Paper No. 1, May 2020 Ben Huf & Holly Mclean Research & Inquiries Unit Parliamentary Library & Information Service Department of Parliamentary Services Parliament of Victoria Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank Annie Wright, Caley Otter, Debra Reeves, Michael Mamouney, Terry Aquino and Sandra Beks for their help in the preparation of this paper. Cover image: Hospital Beds in Great Hall During Influenza Pandemic, Melbourne Exhibition Building, Carlton, Victoria, circa 1919, unknown photographer; Source: Museums Victoria. ISSN 2204-4752 (Print) 2204-4760 (Online) Research Paper: No. 1, May 2020 © 2020 Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Parliament of Victoria Research Papers produced by the Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Department of Parliamentary Services, Parliament of Victoria are released under a Creative Commons 3.0 Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs licence. By using this Creative Commons licence, you are free to share - to copy, distribute and transmit the work under the following conditions: . Attribution - You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non-Commercial - You may not use this work for commercial purposes without our permission. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work without our permission. The Creative Commons licence only applies to publications produced by the -

Tony Cole Is a CDU University Fellow and a Senior Partner, Mercer, Based in Sydney. Over Recent Years He Has Led the Asia Pacific Investment Consulting Business

Presentation by Tony Cole - China and the Lewis Turning Point Tony Cole is a CDU University Fellow and a Senior Partner, Mercer, based in Sydney. Over recent years he has led the Asia Pacific investment consulting business. Tony recently moved to a new role centred on key client consulting, thought leadership. Before joining Mercer in 1996, he was executive director of the Life Investment and Superannuation Association of Australia. Earlier, he served the Australian government in various senior positions, including Chairman of the Industry Commission, Secretary to the Treasury, and Secretary of the Department of Human Services and Health. Tony has a bachelor's degree in economics from the University of Sydney. In 1995, he was awarded an Order of Australia for service to government and industry. Tony was the Chairman of the Advisory Board of the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research for 10 years to 2011. He is a member of the minimum wages panel of Fair Work Australia and of the Advisory Board of the Northern Territory Treasury Corporation. He was a member of the Abbot Government’s Commission of Audit. Tony is also a Trustee Director of the Commonwealth Superannuation Corporation which manages retirement savings for Australian Government employees and a director of Australian Ethical Investors Ltd. China - at a turning point? As the world's largest trader with the world's largest foreign currency reserves and soon to be the World's largest economy, China's economic performance is vital to the world economy - especially during a period when so much of the world economy is in the doldrums. -

South Australian State Public Sector Organisations

South Australian state public sector organisations The entities listed below are controlled by the government. The sectors to which these entities belong are based on the date of the release of the 2016–17 State Budget. The government’s interest in each of the public non-financial corporations and public financial corporations listed below is 100 per cent. Public Public General Non-Financial Financial Government Corporations Corporations Sector Sector Sector Adelaide Cemeteries Authority * Adelaide Festival Centre Trust * Adelaide Festival Corporation * Adelaide Film Festival * Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges Natural Resources * Management Board Adelaide Venue Management Corporation * Alinytjara Wilurara Natural Resources Management Board * Art Gallery Board, The * Attorney-General’s Department * Auditor-General’s Department * Australian Children’s Performing Arts Company * (trading as Windmill Performing Arts) Bio Innovation SA * Botanic Gardens State Herbarium, Board of * Carrick Hill Trust * Coast Protection Board * Communities and Social Inclusion, Department for * Correctional Services, Department for * Courts Administration Authority * CTP Regulator * Dairy Authority of South Australia * Defence SA * Distribution Lessor Corporation * Dog and Cat Management Board * Dog Fence Board * Education Adelaide * Education and Child Development, Department for * Electoral Commission of South Australia * Environment, Water and Natural Resources, Department of * Environment Protection Authority * Essential Services Commission of South Australia -

How the Bank Got Its Groove Back

How the Bank Got Its Groove Back Stephen Bell, Australia’s Money Mandarins: The Reserve Bank and the Politics of Money, Cambridge University Press, 2004 Reviewed by William Coleman his is the story of how the Reserve Bank of Australia won its independence. The tale is told with a trove of interviews of the principal protagonists — Bob Johnston, Bernie T Fraser, John Phillips, Paul Keating. Ian Macfarlane is also interviewed, the only interview, in my reckoning, that he has ever granted. The words used by Macfarlane, and the other central bankers, have a candour and immediacy that constitute a rarity to be prized by central bank watchers in Australia, and abroad. Stephen Bell is to be congratulated. Our story begins in the early 80s, when there was movement in the air. The Campbell Inquiry had reported; a new governor, Bob Johnston was installed. The Bank, however, was slumbering in contented submission to the Federal Government. And this was just how the new Treasurer Paul Keating wanted it to stay. When Keating came into office [in 1983] he clearly assumed the old rules of the game applied. The Treasurer made monetary policy on the advice of the Reserve Bank and the Treasury … . I am sure he came into office firmly of that view … .(Ian Macfarlane) As the Bank was also firmly of that view there was, initially, no lack of mutual confidence. Trust was lost because of Keating’s wrath at the lack of ‘instant action’ in response to his behests. The critical incident came in March 1988, with the resolution to tighten monetary policy. -

CEDA's Top 10 Speeches of 2012

10 CEDA’s Top 10 Speeches of 2012 A collection of the most influential and interesting speeches from the CEDA platform in 2012 CEDA’s Top 10 Speeches of 2012 A collection of the most influential and interesting speeches from the 10CEDA platform in 2012 About this publication CEDA’s Top 10 Speeches 2012 © CEDA 2012 ISBN: 0 85801 285 5 The views expressed in this document are those of the authors, and should not be attributed to CEDA. CEDA’s objective in publishing this collection is to encourage constructive debate and discussion on matters of national economic importance. Persons who rely upon the material published do so at their own risk. Designed by Robyn Zwar Graphic Design Photography: CEDA Photo Library with the exception of page 55 (also repeated on front page). Image of Susan Ryan AO supplied by Australian Human Rights Commission. About CEDA CEDA – the Committee for Economic Development of Australia – is a national, independent, member-based organisation providing thought leadership and policy perspectives on the economic and social issues affecting Australia. We achieve this through a rigorous and evidence-based research agenda, and forums and events that deliver lively debate and critical perspectives. CEDA’s expanding membership includes more than 800 of Australia’s leading businesses and organisations, and leaders from a wide cross-section of industries and academia. It allows us to reach major decision makers across the private and public sectors. CEDA is an independent not-for-profit organisation, founded in 1960 by leading Australian economist Sir Douglas Copland. Our funding comes from membership fees, events, research grants and sponsorship. -

Crime Prevention 2011 and Beyond – a Forum of Key Personnel from the Asia‐Pacific Region

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship SYDNEY INSTITUTE OF CRIMINOLOGY CRIME PREVENTION 2011 AND BEYOND – A FORUM OF KEY PERSONNEL FROM THE ASIA‐PACIFIC REGION Crime Prevention Programs/Initiatives Found to be Particularly Valuable and Relevant in Australia Prepared by: Garner Clancey1 Introductory Remarks I would like to commence by acknowledging and paying respect to the traditional owners of the land on which we meet; the Kaurna people. As we share our own knowledge, teaching, learning and research practices may we also pay respect to the knowledge embedded forever within the Aboriginal Custodianship of Country. I would also like to congratulate and thank the organisers of this event. Many members of the Australian Crime Prevention Council have worked tirelessly for many months to organise this wonderful and important Forum. While many people contribute to the hosting of an event of this nature, special mention must be made of the Organising Committee, which consists of: Master Peter Norman OAM, Chairman, ACPC Judge Andrew Wilson AM, Past President, ACPC Mr John Murray APM, Secretary and Public Officer ACPC Mr Adam Bodzioch, Treasurer ACPC Associate Professor Patrikeeff, Master of Kathleen Lumley College It is an honour to be given the opportunity to speak today and to share some thoughts on promising and valuable Australian crime prevention developments. There are a score of people involved in this event who could equally be providing this address. Many of the Australian representatives here today have been responsible for some of the successful initiatives which I will mention and who deserve considerable credit for the foresight, determination and perseverance to turn good ideas into effective practice. -

Transporting Melbourne's Recovery

Transporting Melbourne’s Recovery Immediate policy actions to get Melbourne moving January 2021 Executive Summary The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted how Victorians make decisions for when, where and how they travel. Lockdown periods significantly reduced travel around metropolitan Melbourne and regional Victoria due to travel restrictions and work-from-home directives. As Victoria enters the recovery phase towards a COVID Normal, our research suggests that these travel patterns will shift again – bringing about new transport challenges. Prior to the pandemic, the transport network was struggling to meet demand with congested roads and crowded public transport services. The recovery phase adds additional complexity to managing the network, as the Victorian Government will need to balance competing objectives such as transmission risks, congestion and stimulating greater economic activity. Governments across the world are working rapidly to understand how to cater for the shifting transport demands of their cities – specifically, a disruption to entire transport systems that were not designed with such health and biosecurity challenges in mind. Infrastructure Victoria’s research is intended to assist the Victorian Government in making short-term policy decisions to balance the safety and performance of the transport system with economic recovery. The research is also designed to inform decision-making by industry and businesses as their workforces return to a COVID Normal. It focuses on how the transport network may handle returning demand and provides options to overcome the crowding and congestion effects, while also balancing the health risks posed by potential local transmission of the virus. Balancing these impacts is critical to fostering confidence in public transport travel, thereby underpinning and sustaining Melbourne’s economic recovery. -

Considering the Creation of a Domestic Intelligence Agency in the United States

HOMELAND SECURITY PROGRAM and the INTELLIGENCE POLICY CENTER THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Homeland Security Program RAND Intelligence Policy Center View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. -

Tasmania (TAS)

Australian Red Cross 26.05.21 COVID-19 Information Sheet – Tasmania (TAS) Disclaimer: The information below should not be considered an exhaustive list and service delivery may change. Please contact organisations and services directly for the most up to date information and to enquire further about eligibility. Red Cross does not determine eligibility for the third party services listed. Government of Tasmania Updates • Tasmanian Government COVID-19 Updates o Tasmanian border restrictions and subsequent quarantine arrangements are classified as low, medium and high. To check the classification of a location visit the Tasmanian government’s coronavirus website. These classifications change depending on the COVID-19 situation in each state and territory. • COVID-19 vaccinations: The Tasmanian and the Australian Governments are working together to give safe COVID-19 vaccinations to the community. Vaccines are being delivered in phases. All Tasmanians aged 18 and over will be able to get vaccinated for free. More information is available on the Tasmanian government website. • Support for Temporary Visa Holders: • Pandemic Isolation Assistance Grants are available to support low-income persons, casual workers and self-employed persons who are required to self-isolate due to COVID-19 risk. To apply, please call the Public Health Hotline on 1800 671 738. • The Rapid Response Skills Initiative provides funding of up to $3,000 towards the cost of training for people who have lost their jobs because they have been made redundant, the place they -

Voting in AUSTRALIAAUSTRALIA Contents

Voting IN AUSTRALIAAUSTRALIA Contents Your vote, your voice 1 Government in Australia: a brief history 2 The federal Parliament 5 Three levels of government in Australia 8 Federal elections 9 Electorates 10 Getting ready to vote 12 Election day 13 Completing a ballot paper 14 Election results 16 Changing the Australian Constitution 20 Active citizenship 22 Your vote, your voice In Australia, citizens have the right and responsibility to choose their representatives in the federal Parliament by voting at elections. The representatives elected to federal Parliament make decisions that affect many aspects of Australian life including tax, marriage, the environment, trade and immigration. This publication explains how Australia’s electoral system works. It will help you understand Australia’s system of government, and the important role you play in it. This information is provided by the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC), an independent statutory authority. The AEC provides Australians with an independent electoral service and educational resources to assist citizens to understand and participate in the electoral process. 1 Government in Australia: a brief history For tens of thousands of years, the heart of governance for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples was in their culture. While traditional systems of laws, customs, rules and codes of conduct have changed over time, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples continue to share many common cultural values and traditions to organise themselves and connect with each other. Despite their great diversity, all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities value connection to ‘Country’. This includes spirituality, ceremony, art and dance, family connections, kin relationships, mutual responsibility, sharing resources, respecting law and the authority of elders, and, in particular, the role of Traditional Owners in making decisions. -

Extending Out-Of-Home Care in the State of Victoria, Australia: the Policy Context and Outcomes

Scottish Journal of Residential Child Care Volume 20.1 Extending out-of-home care in the state of Victoria, Australia: The policy context and outcomes Philip Mendes Abstract In November 2020, the State (Labour Party) Government of Victoria in Australia announced that it would extend out-of-home care (OOHC) on a universal basis until 21 years of age starting 1 January 2021. This is an outstanding policy innovation introduced in response to the Home Stretch campaign, led by Anglicare Victoria, to urge all Australian jurisdictions to offer extended care programmes until at least 21 years. It also reflects the impact of more than two decades of advocacy by service providers, researchers, and care experienced young people (Mendes, 2019). Keywords Care experience, out-of-home care, aftercare, care leaving, extended care, staying put, Australia Corresponding author: Philip Mendes, Associate Professor, Monash University Department of Social Work, [email protected] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License Scottish Journal of Residential Child Care ISSN 1478 – 1840 CELCIS.ORG Extending out-of-home care in the state of Victoria, Australia: The policy context and outcomes Background Australia has a federal out-of-home care (OOHC) system by which transition from care policy and practice differs according to the specific legislation and programmes in the eight states and territories. In June 2019, there were nearly 45,000 children in OOHC nationally of whom the majority (92 per cent in total) were either in relative/kinship care or foster care. Only about six per cent lived in residential care homes supervised by rostered staff.