The Invention and Reception of the Mino'odera Engi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jichihan and the Restoration and Innovation of Buddhist Practice

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1999 26/1-2 Jichihan and the Restoration and Innovation of Buddhist Practice Marc Buijnsters The various developments in doctrinal thought and practice during the Insei and Kamakura periods remain one of the most intensively researched fields in the study of Japanese Buddhism. Two of these developments con cern the attempts to restore the observance of traditional Buddhist ethics, and the problem of how Pure La n d tenets could be inserted into the esoteric teaching. A pivotal role in both developments has been attributed to the late-Heian monk Jichihan, who was lauded by the renowned Kegon scholar- monk Gydnen as “the restorer of the traditional precepts ” and patriarch of Japanese Pure La n d Buddhism.,’ At first glance, available sources such as Jichihan’s biograpmes hardly seem to justify these praises. Several newly discovered texts and a more extensive use of various historical sources, however, should make it possible to provide us with a much more accurate and complete picture of Jichihan’s contribution to the restoration and innovation of Buddhist practice. Keywords: Jichihan — esoteric Pure Land thousfht — Buddhist reform — Buddhist precepts As was n o t unusual in the late Heian period, the retired Regent- Chancellor Fujiwara no Tadazane 藤 原 忠 実 (1078-1162) renounced the world at the age of sixty-three and received his first Buddnist ordi nation, thus entering religious life. At tms ceremony the priest Jichi han officiated as Teacher of the Precepts (kaishi 戒自帀;Kofukuji ryaku 興福寺略年代記,Hoen 6/10/2). Fujiwara no Yorinaga 藤原頼長 (1120-11^)0), Tadazane^ son who was to be remembered as “Ih e Wicked Minister of the Left” for his role in the Hogen Insurrection (115bハ occasionally mentions in his diary that he had the same Jichi han perform esoteric rituals in order to recover from a chronic ill ness, achieve longevity,and extinguish his sins (Taiki 台gd Koji 1/8/6, 2/2/22; Ten,y6 1/6/10). -

Tourists in Paradise Writing the Pure Land in Medieval Japanese Fiction

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 33/2: 269–296 © 2006 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture R. Keller Kimbrough Tourists in Paradise Writing the Pure Land in Medieval Japanese Fiction Late-medieval Japanese fiction contains numerous accounts of lay and monastic travelers to the Pure Land and other extra-human realms. In many cases, the “tourists” are granted guided tours, after which they are returned to the mun- dane world in order to tell of their unusual experiences. This article explores several of these stories from around the sixteenth century, including, most prominently, Fuji no hitoana sōshi, Tengu no dairi, and a section of Seiganji engi. I discuss the plots and conventions of these and other narratives, most of which appear to be based upon earlier oral tales employed in preaching and fund-raising, in order to illuminate their implications for our understanding of Pure Land-oriented Buddhism in late-medieval Japan. I also seek to demon- strate the diversity and subjectivity of Pure Land religious experience, and the sometimes startling gap between orthodox doctrinal and popular vernacular representations of Pure Land practices and beliefs. keywords: otogizōshi – jisha engi – shaji engi – Fuji no hitoana sōshi – Bishamon no honji – Tengu no dairi – Seiganji engi – hell – travel R. Keller Kimbrough is an assistant professor of Japanese Literature at the University of Colorado at Boulder. 269 ccording to an anonymous work of fifteenth- or early sixteenth- century Japanese fiction by the name of Chōhōji yomigaeri no sōshi 長宝 寺よみがへりの草紙 [Back from the dead at Chōhōji Temple], the Japa- Anese Buddhist nun Keishin dropped dead on the sixth day of the sixth month of Eikyō 11 (1439), made her way to the court of King Enma, ruler of the under- world, and there received the King’s personal religious instruction and a trau- matic tour of hell. -

The Shôkyû Version of the Kitano Tenjin Engi Emaki: a Brief Introduction to Its Content and Function

Eras Edition 11, November 2009 – http://www.arts.monash.edu.au/publications/eras The Shôkyû version of the Kitano Tenjin engi emaki: A brief introduction to its content and function Sara L. Sumpter (University of Pittsburgh) Abstract: This article examines the political and social atmosphere surrounding the production of the thirteenth-century hand scroll Kitano Tenjin engi emaki (Illustrated Legends of the Kitano Shrine), which depicts the life, death and posthumous revenge of the ninth-century courtier Sugawara no Michizane. The article combines an analysis of the content and religious iconography of the scroll, a study of early Japanese beliefs in angry spirits of the dead, and a narration of the actual life of Michizane in an attempt to produce a sketch of the rituals and superstitions of Heian and early Kamakura period Japanese society, and to suggest possible functions of the hand scroll that complement them. The hand scroll sets collectively known as the Kitano Tenjin engi emaki (Illustrated Legends of the Kitano Shrine) each tell the story of the life and death of the ninth- century courtier and poet, Sugawara no Michizane (845–903), and of the posthumous revenge undertaken by his vengeful spirit (onryô). According to the scrolls, Michizane was falsely accused of treason by rivals at the Heian court who were jealous of his astronomical rise to power. He was exiled to Dazaifu on the island of Kyushu in 901 and died there two years later in despair. His spirit persisted in seeking retribution against his enemies and in reclaiming his position and honours. He is said to have stalked his numerous rivals in the form of the thunder god (raijin) before ultimately revealing to a frightened court, through a series of intermediaries, the means of his pacification: deification and worship at the Kitano Shrine in Kyoto.1 Today the Kitano Tenjin engi emaki (hereafter referred to as the Tenjin scrolls) number more than thirty extant examples, ranging in date from the early thirteenth century to the nineteenth century. -

Shigisan Engi Shigisan Engi Overview

Shigisan engi Shigisan engi Overview I. The Shigisan engi or Legends of the Temple on Mount Shigi consists of three handscrolls. Scroll 1 is commonly called “The Flying Granary,” Scroll 2 “The Exorcism of the Engi Emperor,” and Scroll 3 “The Story of the Nun.” These scrolls are a pictorial presentation of three legends handed down among the common people. These legends appear under the title “Shinano no kuni no hijiri no koto” (The Sage of Shinano Province) in both the Uji sh¯ui monogatari (Tales from Uji) and the Umezawa version of the Kohon setsuwash¯u (Collection of Ancient Legends). Since these two versions of the legends are quite similar, one is assumed to be based on the other. The Kohon setsuwash¯u ver- sion is written largely in kana, the phonetic script, with few Chinese characters and is very close to the text of the Shigisan engi handscrolls. Thus, it seems likely that there is a deep connection between the Shigisan engi and the Kohon setsuwash¯u; one was probably the basis for the other. “The Flying Granary,” Scroll 1 of the Shigisan engi, lacks the textual portion, which has probably been lost. As that suggests, the Shigisan engi have not come down to us in their original form. The Shigisan Ch¯ogosonshiji Temple owns the Shigisan engi, and the lid of the box in which the scrolls were stored lists two other documents, the Taishigun no maki (Army of Prince Sh¯otoku-taishi) and notes to that scroll, in addition to the titles of the three scrolls. -

Ōita Prefecture

Coor din ates: 3 3 °1 4 ′1 7 .4 7 ″N 1 3 1 °3 6 ′4 5 .3 8″E Ōita Prefecture 大 分 県 Ōita Prefecture ( Ōita-ken) is a prefecture on Ōita Prefecture Kyushu region of Japan.[1] The prefectural capital is the city 大分県 of Ōita.[2] Prefecture Japanese transcription(s) Contents • Japanese 大分県 • Rōmaji Ōita-ken History Notable people Shrines and temples Geography Current municipalities Cities Flag Symbol Towns and villages Mergers and dissolutions Economy Other industries Demographics Culture National Treasures Dance Crafts Religion Architecture Music Arts Sports Tourism Prefectural symbols Country Japan Region Kyushu Miscellaneous topics Island Kyushu Media Transport Capital Ōita Roads Government Expressway and Toll Road • Governor Katsusada Hirose National Highway Railroads Area Airports • Total 6,338.82 km2 Ports (2,447.43 sq mi) Notes Area rank 24th References Population (December 1, 2013) External links • Total 1,177,900 • Rank 33rd • Density 185.82/km2 History (481.3/sq mi) ISO 3166 JP-44 Around the 6th century Kyushu consisted of four regions: code Tsukushi Province, Hi Province, Kumaso Province and Districts 3 Toyo Province. Municipalities 18 Flower Bungo-ume blossom Toyo Province was later divided into two regions, upper (Prunus mume and lower Toyo Province, called Bungo Province and Buzen var. bungo) Province. Tree Bungo-ume tree (Prunus mume After the Meiji Restoration, districts from Bungo and Buzen var. bungo) provinces were combined to form Ōita Prefecture.[3] These Bird Japanese white-eye provinces were divided among many local daimyōs and (Zosterops japonica) thus a large castle town never formed in Ōita. -

The Dharma for Sovereigns and Warriors

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 2002 29/1-2 The Dharma for Sovereigns and Warriors Onjo-ji^ しlaim for Legitimacy in Tengu zoshi H aruko Wakabayashi One of the recurring themes depicted in the i engu zoshi, a set of seven scrolls dated 1296,is the conflict among established temples of Nara and Kyoto. The present article focuses particularly on the dispute between Enryaku-ji (sanmon) and Onjo-ji {jimon) that took place during the thir teenth century as it is depicted in Tengu zoshi. The analysis of the texts, both visual and verbal, reveals that the scrolls are more sympathetic to Onjo-ji than Enryaku-ji. This is evident especially when the verbal texts of the Onjo-ji and Enryaku-ji scrolls are compared. Closer examination of the scrolls also shows that Onjo-ji claims superiority over all other established temples. This study shows how the scrolls reveal the discourse formed by the temples during disputes in the late Kamakura period in order to win sup port from political authorities. Tengu zoshi, therefore, in addition to being- a fine example of medieval art, is also an invaluable source for historical studies of late Kamakura Buddmsm. Keywords: Tengu zoshi —— Onjo-ji — Enryaku-ji — obo buppo soi — narrative scroll (emaki) — ordination platform (kaidan) Tengu zoshi 天狗草紙 is a set of narrative scrolls {emaki,絵巻)dated to 1296.1 The set consists of seven scrolls: the Kofuku-ji 興福寺,Todai-ji fhis article is based on a chapter of my doctoral dissertation, and was revised and pre sented most recently at the Setsuwa Bungakukai in Nagoya, December 2001.I wish to thank Kuroda Hideo, Abe Yasuro, Harada Masatoshi, and my colleagues Saito Ken’ichi,Fujiwara Shigeo, and Kuroda Satoshi for reading and commenting on my drafts. -

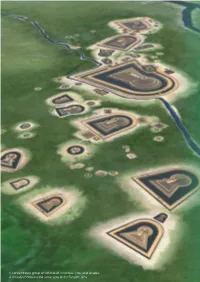

A Concentrated Group of Kofun Built in Various Sizes and Shapes a Virtually Reconstructed Aerial View of the Furuichi Area Chapter 3

A concentrated group of kofun built in various sizes and shapes A virtually reconstructed aerial view of the Furuichi area Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb group of the king’s clan and the clan’s affiliates that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago and took charge of diplomacy with contemporary East Asian powers. The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period, characterized by construction of distinctive mounded tombs called kofun. A set of 49 kofun in 45 component parts is located on a plateau overlooking the bay which was the maritime gateway to the continent, in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important political cultural centers. The property includes many tombs with plans in the shape of a keyhole, a feature unique in the world, on an extraordinary scale of civil engineering work in terms of world-wide constructions; among these tombs several measure as much as 500 meters in mound length. They form a group, along with smaller tombs that are differentiated by their various sizes and shapes. In contrast to the type of burial mound commonly found in many parts of the world, which is an earth or piled- stone mound forming a simple covering over a coffin or a burial chamber, kofun are architectural achievements with geometrically elaborate designs created as a stage for funerary rituals, decorated with haniwa clay figures. -

Basic Study on Oharidadera and Taikoji Temples

Bulletin of the National Museum of Japanese History Vol. 179 November 2013 Basic Study on Oharidadera and Taikoji Temples YOSHIKAWA Shinji The abandoned temple of Okuyama (Okuyama Kumedera Temple) located at Okuyama in Asuka Village, Nara Prefecture is considered to be an old temple founded in the 620s or 630s, and identified with the Oharidadera Temple found in bibliographical sources of olden times. However, with regard to the circumstances of the foundation of the Oharidadera Temple, to date, no firmly established theory has been formed. In this paper by rereading historical materials relating to ancient times through to the medieval period, the following conclusions were obtained. 1. Oharidadera Temple in Asuka was the leading convent in the late 7th century, and even in the 8th century the temple had a close relation with the Imperial Family. It was confirmed that concurrently with the relocation of the capital to Heijyo-kyo, the temple was moved to the northern outskirts of Heijyo-kyo, and the new temple was also called Oharidadera. 2. The Taikoji Temple in Nara, mentioned in historical materials covering the Heian period and later, in view of its geographical position, can be assumed to be the same as the Heijyo Oharidadera Temple. It would be reasonable to consider that Oharidadera Temple had the Buddhist name, Taikoji, since before the relocation of the capital to Heijyo-kyo. 3. Private estates owned by Taikoji Temple in Yamato Province, mentioned in the Kanyo Ruijusho collection, were systematically arranged in locations convenient for overland transportation on the Nakatsu-Michi road and water transport on the Yamato River; against this background a strong admin- istrative and financial power can be inferred. -

Island Narratives in the Making of Japan: the Kojiki in Geocultural Context

Island Studies Journal, Ahead of print Island narratives in the making of Japan: The Kojiki in geocultural context Henry Johnson University of Otago [email protected] Abstract: Shintō, the national religion of Japan, is grounded in the mythological narratives that are found in the 8th-Century chronicle, Kojiki 古事記 (712). Within this early source book of Japanese history, myth, and national origins, there are many accounts of islands (terrestrial and imaginary), which provide a foundation for comprehending the geographical cosmology (i.e., sacred space) of Japan’s territorial boundaries and the nearby region in the 8th Century, as well as the ritualistic significance of some of the country’s islands to this day. Within a complex geocultural genealogy of gods that links geography to mythology and the Japanese imperial line, land and life were created along with a number of small and large islands. Drawing on theoretical work and case studies that explore the geopolitics of border islands, this article offers a critical study of this ancient work of Japanese history with specific reference to islands and their significance in mapping Japan. Arguing that a characteristic of islandness in Japan has an inherent connection with Shintō religious myth, the article shows how mythological islanding permeates geographic, social, and cultural terrains. The discussion maps the island narratives found in the Kojiki within a framework that identifies and discusses toponymy, geography, and meaning in this island nation’s mythology. Keywords: ancient Japan, border islands, geopolitics, Kojiki, mapping, mythology https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.164 • Received July 2020, accepted April 2021 © Island Studies Journal, 2021 Introduction This study interprets the significance of islands in Japanese mythological history. -

Creating Heresy: (Mis)Representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-Ryū

Creating Heresy: (Mis)representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-ryū Takuya Hino Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Takuya Hino All rights reserved ABSTRACT Creating Heresy: (Mis)representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-ryū Takuya Hino In this dissertation I provide a detailed analysis of the role played by the Tachikawa-ryū in the development of Japanese esoteric Buddhist doctrine during the medieval period (900-1200). In doing so, I seek to challenge currently held, inaccurate views of the role played by this tradition in the history of Japanese esoteric Buddhism and Japanese religion more generally. The Tachikawa-ryū, which has yet to receive sustained attention in English-language scholarship, began in the twelfth century and later came to be denounced as heretical by mainstream Buddhist institutions. The project will be divided into four sections: three of these will each focus on a different chronological stage in the development of the Tachikawa-ryū, while the introduction will address the portrayal of this tradition in twentieth-century scholarship. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations……………………………………………………………………………...ii Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………iii Dedication……………………………………………………………………………….………..vi Preface…………………………………………………………………………………………...vii Introduction………………………………………………………………………….…………….1 Chapter 1: Genealogy of a Divination Transmission……………………………………….……40 Chapter -

OFFICIAL GAZETTE GOVERNMENT PRINTINGBUREAU ENQLISH EDITION Ia*)--I―'4-S―/I:-I-I-Ak^Asefts^I

f OFFICIAL GAZETTE GOVERNMENT PRINTINGBUREAU ENQLISH EDITION ia*)--i―'4-s―/i:-i-i-aK^asefts^i No. 910 WEDNESDAY, APRIL 13, 1949 Price 28.00 yen of currencies and kinds of such financial instru- MINISTERIAL ORDINANCE ・ ments as indicated by foreign currencies and to be impounded by the Government in accordance Ministry of Communications Ordinance with the provisions of Article 4 of the said Cabinet No. 11 Order shall be determined as follows: April 13, 1949 Minister of Finance Regulations for Ministry of Communications IKEDA Hayato Mutual Aid Association(Cabinet Ordinance No. 30 Minister of Commerce & Industry of September, 1945),Special Regulations for Mini- INAGAKI Heitaro stry of Communications Mutual Aid Association 1. The name of owner and quantity of gold to be Camp-followers (Ministry of Communications Ordi- purchased by the Government in accordance with nance No. 97 of November, 1941) and Regulations the provisions of Article 1 of the Cabinet Order for Ministry of Communications Mutual Aid Asso- concerning gold, foreign currencies and foreign ciationsSeamen Insurance Members (Cabinet Ordi- financial instruments (Cabinet Order No. 52 of nance No. 33 of September, 1945) shallbe abolished. 1949; hereinafter to be called Order): Minister of Communications Name of owner: MINOMO Nagashiko OZAWA Saeki' Quantity: 50 gram Supplementary Provision: 2. The units of foreign currencies to be purchased The present MinisterialOrdinance shall come by the Government in accordance with the pro- into force as from the day of its promulgation and visions of Article 1 of the Order: shallbe applied as from July 1, 1948. ££■,£ Countries 1. Republica Argentina Pesos NOTIFICATIONS 2. -

Encyclopedia of Japanese History

An Encyclopedia of Japanese History compiled by Chris Spackman Copyright Notice Copyright © 2002-2004 Chris Spackman and contributors Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.1 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, with no Front-Cover Texts, and with no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License.” Table of Contents Frontmatter........................................................... ......................................5 Abe Family (Mikawa) – Azukizaka, Battle of (1564)..................................11 Baba Family – Buzen Province............................................... ..................37 Chang Tso-lin – Currency............................................... ..........................45 Daido Masashige – Dutch Learning..........................................................75 Echigo Province – Etō Shinpei................................................................ ..78 Feminism – Fuwa Mitsuharu................................................... ..................83 Gamō Hideyuki – Gyoki................................................. ...........................88 Habu Yoshiharu – Hyūga Province............................................... ............99 Ibaraki Castle – Izu Province..................................................................118 Japan Communist Party – Jurakutei Castle............................................135